By Jon Diamond

Historians began writing about the Civil War even before it had become history. Battlefield accounts by traveling correspondents were a staple of Northern and Southern newspapers during the war, and a flood of memoirs, letters, official records, and unit histories followed in the decades after the war. Novelists, short story writers, and poets such as John W. De Forest, Ambrose Bierce, and Sidney Lanier, who had served in the war, and the brilliant 24-year-old prodigy Stephen Crane, who was not even born until six years after the Civil War ended, added their voices to the mix. In the ensuing century and a half, American libraries have filled countless shelves with books devoted to the most pivotal event in the nation’s history.

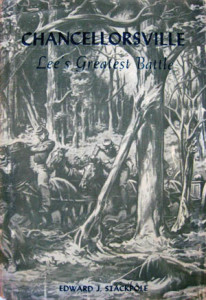

Inevitably, many of those books have faded from view, while others have stood the test of time to become acknowledged classics of Civil War history. Among the latter is retired U.S. Army General Edward J. Stackpole’s 1958 study, Chancellorsville: Lee’s Greatest Battle. Published by his family-owned company, Stackpole Books, just prior to the Civil War centennial, Stackpole’s meticulous and incisive study was instantly successful, both critically and popularly. Considered by many to be Stackpole’s greatest contribution to Civil War literature, the work remains a favorite of Civil War enthusiasts and a textbook example of how to think and write about the war.

Stackpole’s Wars

Stackpole was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1894 and graduated from Yale University in 1915. During World War I he served as a company commander of the 28th “Keystone” Division, 110th Infantry, in France in 1918 and was wounded three times. The author’s dedication in Chancellorsville reads: “To the men of my Company M, 110th Infantry, 28th Division, American Expeditionary Forces, World War I, of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, who fought and died on the battlefields of France.” Stackpole recovered from his wounds at Walter Reed Army Hospital and reentered the National Guard as commanding officer of the 104th Cavalry. He later commanded the 52nd Cavalry Brigade and ultimately the 22nd Cavalry Division.

In 1940, at his own request, Stackpole took a reduction in rank to return to active duty, heading a brigade during World War II before being sent to Panama to serve as commanding general of the Canal Zone. In 1943, he returned stateside to serve as chairman of the War Department Manpower Board Office for General George C. Marshall. After the war, Stackpole commanded the 28th Division. He retired as commander of the Pennsylvania National Guard in 1947 following his reorganization of the division in 1946. His military honors included the Distinguished Service Cross, the Purple Heart with two clusters, Legion of Merit, and the Pennsylvania Distinguished Service Medal, in addition to campaign ribbons for service in the two world wars.

Stackpole Books

Stackpole Books had its origins in the Evening Telegraph, a Harrisburg newspaper dating back to the early 19th century. In 1901, E.J. Stackpole, Sr., the general’s father, acquired controlling interest in the Telegraph Press. In 1930, the National Service Publishing Company of Washington, D.C., which had been established in 1921, was acquired by the Telegraph Press. Under Stackpole’s direction, it was renamed Military Service Publishing Company and began publishing military textbooks. In that same year Stackpole and his brother, Albert, founded Stackpole Sons, which published books on a variety of subjects, both fiction and nonfiction. During World War II, it produced a popular series of paperbacks for GIs to read in the foxholes. Both Stackpole Sons and Military Service Publishing Company were subsidiary divisions of the Telegraph Press organization. In the 1950s, Stackpole Sons continued its strong emphasis on nonfiction books, especially historical works and outdoor titles. In 1959, Stackpole Sons and Military Service Publishing Company merged into Stackpole Books.

In time, General Stackpole would author five books on the Civil War, receiving an honorary degree from Gettysburg College in 1961 for his historical contributions. When his grandson, M. David Detweiler, was asked what had initially stimulated Stackpole’s interest in the Civil War, he answered: “The General was searching for a book on the Battle of Gettysburg that was not a highly-detailed military text but rather a very readable book in a popular style. When he could not find one, his son-in-law, Meade Detweiler III, suggested that the General write it himself and, thus, began his prolific output of Civil War books.” Stackpole’s first book, They Met at Gettysburg, was published in 1956. Drama on the Rappahannock: The Fredericksburg Campaign appeared a year later.

Lee’s Dilemma at Chancellorsville

In 1958, the general completed his book on Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Chancellorsville campaign. He began by noting that in early 1863 Lee faced a dilemma. As Stackpole wrote: “While the Union defeat at Fredericksburg was a clear-cut military success for the Confederacy, it was in a sense just as barren a victory as Chancellorsville would prove to be, for Lee’s army was unable to exploit either success and could ill afford the cumulative loss of manpower suffered in the two great battles.” It was this manpower issue that would force Lee to act with such offensive spirit, repeatedly dividing his forces to deal blows to the overwhelming size of the Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Lee’s defensive line extended for more than 25 miles, Stackpole noted, “and so [he] disposed his troops [so] that he could quickly concentrate a sufficient number anywhere along the line to seal off or drive back any attack” by Hooker. Part of this manpower deficiency stemmed from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Lee’s I Corps commander, being sent in mid-March to forage for supplies around Suffolk. Accompanying him were the 13,000 troops in the divisions of Maj. Gens. John Bell Hood and George Pickett.

According to the author, “Lee’s hard-hitting divisions had learned well the lesson of flexibility. The capabilities of his corps and division commanders were such that Lee was better able than the Federals to utilize to advantage the principle of mass, which simply means the capability to bring to bear at the right place, at the right time, the number of divisions necessary to accomplish the mission.” The 20th-century general regarded Lee with a measure of awe: “The more one studies Robert E. Lee’s character and leadership qualities, the greater does his stature grow. Many thoughtful, historically minded persons have rightly appraised him as the most eminent of American military commanders, collaterally according him a place in the roster of great captains of all time.” Stackpole placed a premium on Lee’s superior intellect as well: “This was clearly demonstrated in all his planning, in his decisions, and above all in his analysis of military intelligence. He was especially adept in divining the most probable line of action of his opponents and in devising countermoves best calculated to nullify those actions.”

“A Two to One Advantage in Numbers”

As a combat infantry officer and division commander himself, Stackpole chose to write about the May 1863 Virginia battle in which the overwhelmingly outnumbered Lee audaciously continued to divide his forces as “tactical equalizers” to defeat the larger Union Army of the Potomac under Hooker. Stackpole carefully discerned the situational nuances between Lee and Hooker: “Lee had elected to remain on the tactical defensive for the time being to see what his new opponent might be planning. If by that date [first of May] Hooker had not put his army in motion or given a clear indication of his intentions, Lee would take the offensive himself to bring matters to a head.” Lee’s thinking centered on the military maxim that when one is too weak to defend, attack instead. Hooker incorrectly thought that Lee would remain on the defensive or withdraw when attacked. Instead, said Stackpole, Lee “had an uncanny knack, which many regarded as intuition, of anticipating just about how his opponents would react under varying conditions.”

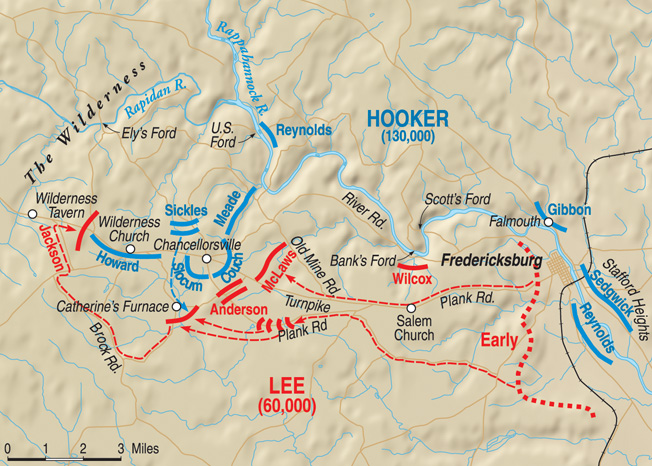

Stackpole sketched the battle’s start as it was on April 29: “Hooker’s army had more than a two to one advantage in numbers. [Lee’s] own cavalry had less than half its normal strength, while an entire corps of enemy cavalry, 10,000 strong and more aggressive than usual, was cutting in on the rear. His opponent had just sprung a surprise on him by a concealed march of three army corps in a wide swing, miles to the west of the fords where Lee had anticipated a crossing. This enemy was now on his left rear while another large troop concentration was threatening Fredericksburg.” On April 30, Hooker arrived at the Chancellor House and set up camp. In Fredericksburg, Lee tried to determine if the greater threat lay on his left flank with Hooker or with Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s VI Corps, Federal troops stationed opposite him at the site of his previous December 1862 victory on the heights above Fredericksburg. Lee correctly determined his greatest peril was to the west with Hooker. The stage was set for Lee’s military masterpiece.

“Hooker Lost His Nerve!”

On May 1, the first day of the battle, Lee sent word to Confederate President Jefferson Davis: “Their intention is to turn our left, and probably our rear. Our condition favors their operations.” Presciently, on April 29, in the first of his strategic troop partitions to confront Hooker’s movements, Lee had ordered Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson to move west from north of Fredericksburg toward Chancellorsville. This was to block any Federal movement east toward Fredericksburg, which would threaten Lee’s rear and perhaps create a path for Hooker to advance on Richmond. Anderson’s troops arrived at dawn on April 30 and spent the rest of the day digging trenches and throwing up breastworks. Also on April 30, Lee ordered Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws down from Fredericksburg to support Anderson.

Lee’s other adjustment was to get Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart’s two cavalry brigades to rejoin him with the main Confederate Army. Stuart had sent a message to Lee reporting that three Federal corps had crossed the Rapidan River and were heading southeast to get at Lee’s rear. Stackpole characterized Lee at this moment: “No more time was to be lost. Lee’s decision was to attack, and the orders to put his army into position were quickly made ready. Lee’s decision was a courageous one, in the Lee tradition. Who but Robert E. Lee would have the strategic insight and moral courage to assume the heavy risk of further dividing his forces? On the other hand, who but he had such perfect confidence in his officers and men and such calm assurance that with God’s blessing all would be well?”

At dawn on May 1, Lee and Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson surveyed the Federals across the river from Fredericksburg. Lee noted that the enemy was barely active and predicted to Jackson that the Union attack would come from Chancellorsville. Lee was a gambler, and he took a bold risk to attack in his numerically inferior state. He decided to leave behind a token force under Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early to cover Sedgwick at Fredericksburg and ordered Jackson to take his remaining divisions to strike Hooker at Chancellorsville.

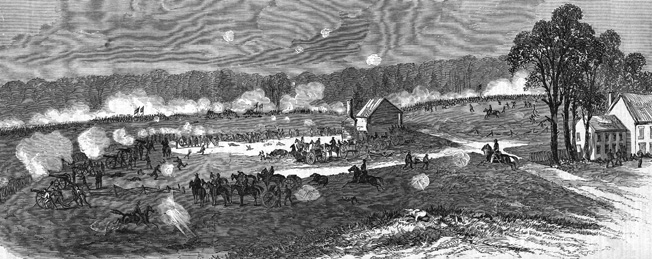

By 11 am, Jackson was in motion, quick-marching his 31,000 troops westward to meet Hooker’s more numerous divisions, which were moving from Chancellorsville toward Fredericksburg. Fighting soon commenced on the Orange Turnpike, eventually forcing Hooker’s troops back toward Chancellorsville. This unexpected Confederate resistance badly unnerved the Union leader. Hooker’s strategy called for a Confederate retreat—yet Lee was attacking. At that moment, Hooker lost the strategic initiative and ordered all units to withdraw from the attack and resume their original positions. Thus, on the first day of the battle, Lee had already taken charge of the ebb and flow of the conflict. As Stackpole wrote bluntly, “Hooker lost his nerve!”

“Jackson’s Historic Flank March”

After the fighting of May 1 subsided, Jackson proposed a bold plan to Lee based on Stuart’s reconnaissance. Essentially, the Union army’s right flank was adjacent to heavy woods, with only a few pickets posted. Stackpole wrote: “Lee and Jackson exchanged glances. It was good news that Stuart brought, and the case for a flank maneuver became a determination in the minds of the two leaders.” Jackson would take almost his entire II Corps (28,000 troops) before dawn the next day on a westerly march and then attack eastward against the unprotected Union right flank (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps). This would constitute Lee’s third partition of his army in the face of the enemy. Lee would be left with only Anderson’s and McLaws’s divisions facing the Union army and keeping it in check. With these remnant divisions, Lee would feign an attack, thereby enabling Jackson to steal a march on Hooker. At the same time, Lee admonished his divisional commanders to attack if a favorable opportunity presented itself. Even when Lee was conducting a holding action, his mind never wandered far from the offensive if he could inflict greater harm on the enemy.

The thick woods in the Virginia Wilderness concealed many paths and rural roads known only to locals. The Brock Road met the Orange Turnpike just east of the Wilderness Tavern, a little more than a mile west of Howard’s open right flank. The object of Jackson’s march was to strike Hooker’s rear. Lee envisioned that by the nightfall of May 2, his Army of Northern Virginia would either have broken the Union Army’s right flank, or that he would be forced to withdraw toward the railroads to cover Richmond. At 4 am on May 2, Jackson commenced what Stackpole referred to as “Jackson’s Historic Flank March” around Hooker’s army to strike the flank of Howard’s XI Corps.

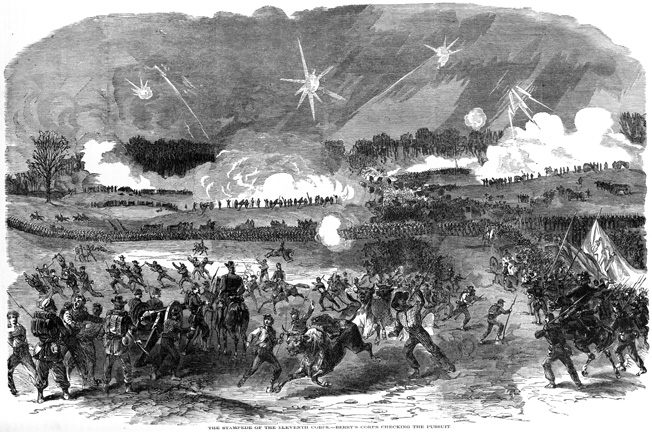

At 2:30 pm, the leading elements of Jackson’s force, under Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes, formed up north of the Orange Turnpike just to the west of Howard’s corps. Despite warnings from Hooker to strengthen his flank and reports from his pickets of suspicious Confederate activity, Howard did not create any meaningful defenses, trusting the dense woods to provide ample protection for his corps. With sunset at it back, Jackson’s II Corps attacked at roughly 5 pm, turning the entire Federal flank. Elements of Howard’s corps broke under the Confederate onslaught and began a headlong retreat. After the initial attack, the Confederates reformed to mount a night attack on Hooker’s Federal line, which Jackson’s assault had threatened to collapse. However, Hooker’s easternmost units at Chancellor House formed a defensive line by 8 pm and checked any further extent of the Confederate high tide.

As darkness and fog cloaked the battlefield, Jackson and his staff were reconnoitering at 9:15. Confederate troops of a North Carolina regiment mistakenly identified Jackson’s contingent as Union cavalry and fired on it, mortally wounding the great Stonewall. Lee’s II Corps commander was struck in the left lower and upper arm as well as his right hand, and although his wounds were healing, he died from pneumonia a week later. A great turning movement against phenomenal odds was marred by the loss of Jackson. Lee turned over II Corps command to Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, who likewise was wounded. Stuart temporarily took command of II Corps. Stackpole praised Lee’s strategic vision and moral courage in planning “one of the great flank marches of military history. The specific blueprint and the execution were entrusted to Stonewall Jackson.”

Hazel Grove: A “Natural Artillery Park”

In the predawn hours of May 3, Lee ordered Stuart to push Hooker’s line farther back and then unite to form a continuous front against the Army of the Potomac. The rationale for this was that during the night of May 2, Hooker’s army had reformed and now separated Lee from Stuart with an imposing obstacle of manpower. At dawn, Stuart ordered some of his brigades forward in the direction of a “natural artillery park” called Hazel Grove. Contemporaneous with Stuart’s move, Hooker visited Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, whose troops thrust out into a salient controlling Hazel Grove, and ordered him to abandon this site. As Sickles withdrew, Stuart’s troops, under Brig. Gen. James J. Archer, advanced into Hazel Grove and took the position from Sickles’s rear guard of Pennsylvania infantry.

This was a tactical breakthrough for Lee since his artillery commander, Colonel E. Porter Alexander, had decided earlier that Hazel Grove was the “ideal artillery park to slam round after round into Hooker’s line” as well as against the Federal artillery park on Fairview Knoll. Alexander’s possession of Hazel Grove enabled him to effect counter-battery fire against the Union guns on Fairview Knoll and, as the struggle progressed, force Hooker to abandon the Chancellorsville crossroads and ultimately Fairview Knoll. At 9:15 am, as Hooker was leaning against a column of the Chancellor House, an artillery shell hit the house and so disoriented the Army of the Potomac’s commander that he was unable, at a decisive point in the day’s conflict, to function. The first thing Hooker did after regaining his lucidity was to ride off in search of a new headquarters.

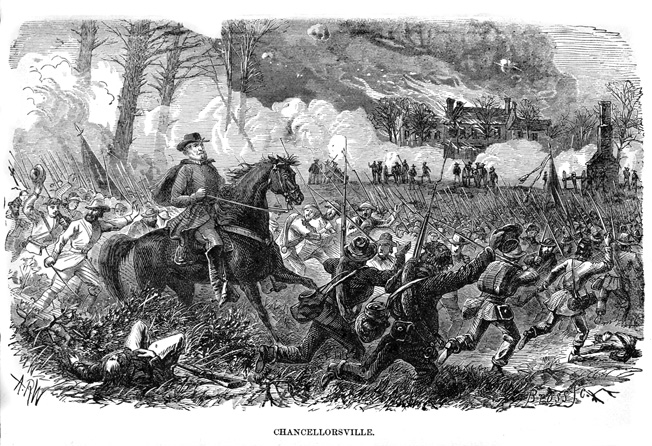

It was now time for Lee’s troops under Anderson and McLaws to enter the fray, pressing the Union line from the south and thereby forcing the Federals to bend back to back with other units. The only direction for the Union troops to withdraw was northerly, and it was becoming apparent that Hooker’s initial position at Chancellorsville was becoming untenable. As Stackpole recounted: “By ten o’clock the field surrounding the Chancellor House had been vacated by the Federals, all of whom had retired in fairly good order to the north. Lee rode up to the ruined and still fiercely burning house. His weary, powder-blackened men suddenly awoke to a realization of the magnitude of their triumph and began to cheer for their commanding general.” Stackpole added his own voice to those cheers: “The sun of his destiny was at its zenith. All that he earned by a life of self-control, all that he had received in inheritance from pioneer forebears, all that he had merited by study, by diligence, and by daring, was crowned into that moment.”

To the east, Sedgwick outnumbered Early’s Confederates by a three to one margin. On May 2, Hooker exhorted Sedgwick to advance past Fredericksburg and attack Lee’s rear. Finally, one day later, Sedgwick’s forces began their attack against Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s brigade of Mississippians, an attack Stackpole termed the Second Battle of Fredericksburg. After two unsuccessful attempts to dislodge the Confederates, entrenched behind a stone wall, a third charge succeeded in opening the road to Chancellorsville and Lee’s rear. Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s brigade of Anderson’s division raced back east to assist Barksdale at Fredericksburg; however, it was too late.

Knowing that reinforcements from Chancellorsville would reach him if he could delay the Union advance, Wilcox hastily erected field works at Salem Church. As Wilcox prepared to meet Sedgwick’s attacking force, Confederate reinforcements from McLaws’s and Anderson’s divisions, under Lee’s direct command, arrived, leaving Stuart back in command of a tiny force to contain Hooker. This constituted Lee’s fourth strategic partition of the Army of Northern Virginia in the face of the numerically superior Army of the Potomac. The men of Anderson’s and McLaws’s divisions held against Sedgwick, enabling Lee to win the Battle of Salem Church. Lee now planned to attack Sedgwick, but McLaws and Early were unable to orchestrate a concentrated attack.

“What Will the Country Say?”

The next day, Early recaptured Marye’s Heights above Fredericksburg to cut off Sedgwick’s possible retreat to Fredericksburg. Lee ordered Early to strike Sedgwick’s left and rear and attempt again to link up with McLaws. Lee arrived at noon with the remainder of Anderson’s division, taking up positions between McLaws at Salem Church and Early back in Fredericksburg. Lee was eager to engage Sedgwick and deal his troops a mortal blow. As Stackpole stated, “Once more Hooker’s plan had backfired; instead of pocketing Lee between wings of the Union army, Sedgwick now found himself in a comparable position, with Confederate troops on his front and rear.”

Again the Confederate forces under Lee could not execute an effective attack. Sedgwick’s VI Corps recrossed the Rappahannock River, this time to the west of Fredericksburg. Hooker convened a council of his subordinates, and although some still wanted to attack the Confederates, Hooker wanted to retreat using the protection of Washington as his pretext. On May 5 and 6, Hooker recrossed the U.S. Ford of the Rappahannock River, ending the Chancellorsville campaign.

Abraham Lincoln was overwrought with the news of yet another defeat. “What will the country say?” he fumed. “Think of it, 130,000 magnificent soldiers cut to pieces by 60,000 half-starved ragamuffins!” The end of the 1863 campaign in the Wilderness of Virginia was the start of the Gettysburg campaign. Lee would wait for Longstreet to arrive from Suffolk, but he knew that he would have to invade the North in the summer of 1863 to compel Lincoln to abandon the war or, alternatively, to garner European recognition of Confederate sovereignty. Lee was already planning to threaten the Federal capital, Baltimore, and Harrisburg.

“He Was a Natural Leader of Men”

Stackpole’s analysis of Lee’s performance at Chancellorsville drew on his own experience as a 20th-century general.

Stackpole praised Lee’s performance fulsomely: “Lee was so vastly superior to Hooker in every category that he could afford to violate fundamental military principles at frequent intervals during the campaign, and did so, each time with impunity because of the marked deficiency of his opponent. It is considered a cardinal strategic sin for a commander to divide his forces in the presence of the enemy and thus risk the danger of being defeated in detail. Lee did just that not once, but four distinct and separate times.”

Following his book on Chancellorsville, Stackpole published two other Civil War studies: From Cedar Mountain to Antietam (1959) and Sheridan in the Shenandoah (1961). And though by then he was long since retired from military life, Stackpole was always referred to by his rank. As historian Robert H. Fowler noted in his prologue to the third edition of Stackpole’s They Met at Gettysburg, “To everyone except for a few of his contemporaries, he was ‘the General.’ It was unthinkable to call him anything else. He was a natural leader of men.”

Stackpole died in 1967 and was buried in Harrisburg. The company that bears his name relocated in 1993 to Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, where it continues to publish a wide variety of works of military reference, the outdoors, general history, crafts, and regional travel. Chancellorsville, it could be said, was all those things.

The author wishes to thank M. David Detweiler, grandson of General Stackpole and President/CEO of Stackpole, Inc. in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, for providing insight into his grandfather’s military and literary careers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments