by Joshua van Dereck

At the beginning of 1861, Missouri was in turmoil. A slave state since its inception in 1820, Missouri had grown increasingly tied to urban industry. Cotton and tobacco had given way to factories, and transplanted northerners and foreign immigrants were flocking to the cities. The election of Republican Party candidate Abraham Lincoln as president the previous November underscored the potential for armed conflict between northern and southern states. As a vital border state, Missouri was a prize much sought by both sides.

Governor Claiborne Jackson was among the old guard who felt that Missouri’s destiny lay with the South. Dismayed when a state convention voted to maintain Missouri’s place in the Union, Jackson nevertheless decreed that Missouri would not furnish a single man for what he termed the “unholy crusade” of war against the South. Missourians wanted no part of civil war, and they made their loyalties known by volunteering heavily for service in home guard units, resolving to fight against aggression from either North or South while walking the delicate tightrope of neutrality.

[text_ad use_post=”455″]

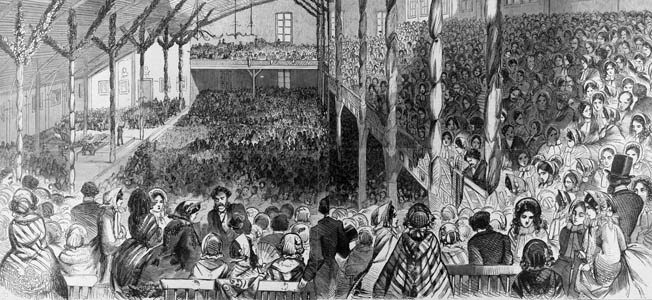

In St. Louis, however, belligerent partisans threatened the balance. St. Louis was Missouri’s largest city, and as a prominent trade center it was home to some of the most radical factions. The German immigrant community, 50,000 strong, was staunchly Unionist. Having come to America for the promise of suffrage and personal liberty, Germans were eager to uphold the integrity of the national trust. By early 1861, German fellowship societies throughout St. Louis had begun organizing makeshift military companies and drilling under the instruction of veterans of the Prussian Army. Concurrently, groups of those who favored the South, drawn heavily from genteel old-guard families, formed Minute Men companies and also began drilling, sometimes only blocks away from their would-be adversaries.

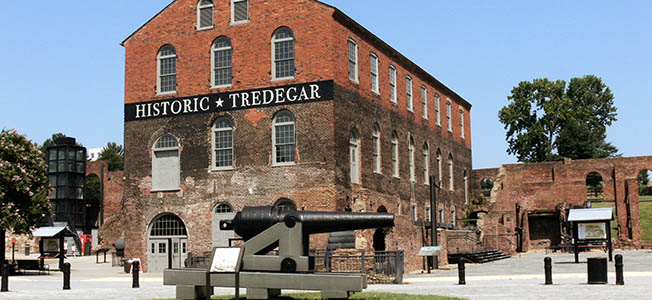

As tensions grew, the rival factions began to raise concerns about the safety of the city’s massive arsenal. St. Louis contained the largest arsenal of any slave state, and its tiny garrison was woefully insufficient for its defense. Alarmed by the situation, Republican Congressman-elect Frank Blair, brother to President Lincoln’s newly appointed postmaster general, telegraphed Washington and urged the immediate reinforcement of the arsenal. Notorious for his truculent outspokenness, Blair resorted to irregular measures to augment the arsenal’s defenses. Preempting Jackson’s refusal to enlist troops for the Federal government, Blair began working covertly to arm the volunteer German companies, initiating a subscription drive for musket funds when he was unable to obtain arms from the arsenal itself.

Nathaniel Lyon Joins the Ranks

Although the Army’s Western Department commander, Brig. Gen. William Harney, shared Blair’s concerns, he favored a more cautious approach, hoping to maintain peace in St. Louis through moderation. Instead of mustering the German volunteers, he brought in a modest reinforcement of U.S. Army regulars, drawn from nearby garrisons. Among the reinforcing contingent was a volatile New England-born captain, Nathaniel Lyon, who soon would prove the undoing of all attempts at conciliation.

Lyon, a native of Connecticut, harbored a deep-rooted hatred of secession, and his reputation for insubordination preceded him. Reaching St. Louis at the head of his company, he proved an immediate headache for Harney, insisting upon 24-hour perimeter patrols around the arsenal and vehemently urging the construction of firing platforms along the arsenal walls so that marksmen and artillerists could rake all approaches to the building—regardless of potential civilian casualties. Making matters worse, Lyon and Blair forged an instant alliance, with Lyon promising to arm and muster any and all Union volunteers regardless of Missouri state directives. He urged Blair to arrange Harney’s removal from command.

Nathaniel Lyon was hardly an iconic hero. An impulsive cigar smoker who loved candy and sported a mouth full of false teeth, he was a martinet of the first order who believed that he existed as a divine instrument of justice. Devoted to draconian discipline within his command, he had developed a reputation in the Regular Army for administering punishments that bordered on torture and sadism. He was even court-martialed for illegal, arbitrary, and unmilitary conduct in the violent disciplining of a private.

Harney Loses His Grip

Harney did what he could to control the situation through formal channels, but he had no authority over Blair, and time was against him. With rumors afoot of secessionist activity in the Missouri countryside, Blair grew ever more determined to see to it that the German volunteers were formally mustered into Federal service. On April 21, Blair tapped powerful contacts in Washington and Pennsylvania, urging Harney’s removal in the interest of security. In response, directives arrived removing Harney and elevating Lyon to department command. German volunteers immediately elected Lyon a brigadier general, and he spent the rest of the week fortifying the arsenal and mustering recruits into the Army, overriding the express wishes of the state government.

Nathaniel Lyon’s ascension provoked fear and anger in St. Louis, and the city erupted with violent disturbances. In the capital at Jefferson City, Governor Jackson, who had already commenced secret negotiations with Confederate President Jefferson Davis, called out the state militia on the pretense of protecting Missouri from outside agitators. Militiamen began converging on camps throughout the state.

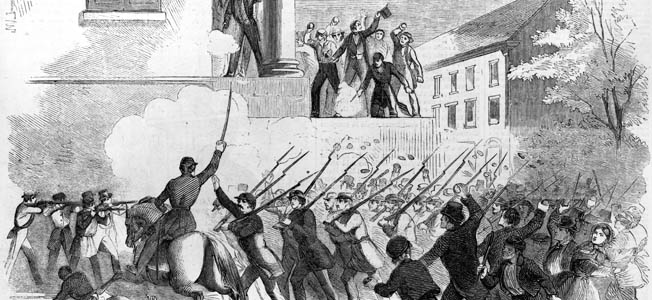

St. Louis became home to Camp Jackson (named for the governor), a base that attracted some 900 volunteers whose ranks included many of the pro-southern Minute Men. Their presence deeply incensed Lyon. Emboldened by the considerable growth of his arsenal force (it was now almost 8,000 strong), he determined to capture the camp, and after scouting the camp himself he returned to the arsenal, continuing to make preparations to fight.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments