By A.B. Feuer

The capture of Guantànamo Bay, Cuba, by U.S. Marines in 1898 was a brief but violent phase of the Spanish-American War. Overshadowed by the more publicized land and sea battles—and largely ignored by historians—the ramifications of this victory would have far-reaching consequences in future relationships between Cuba and the United States.

Bloody Conflict Between Insurgents & Spain

Guantànamo Bay was commercially important to the Cuban economy because of the sugar port of Caimanera on the western shore of the inner bay—about five miles from the open sea. At the entrance to the outer bay—Fisherman’s Point—a busy fishing village sprawled on a sandy beach beneath 30-foot cliffs. The Spaniards used the villagers to pilot ships entering the bay and bound for Caimanera.

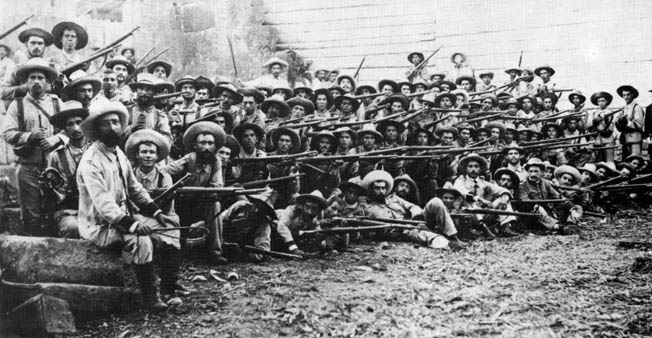

The Cubans had been in revolt against their Spanish masters since 1895. But after three years of bloody fighting, the conflict was still unresolved. The Cuban insurgents controlled only two provinces on the island—while the rest of the country was under the heavy fist of the Spaniards.

Spanish troops held Guantànamo City, Caimanera, and the railroad connecting the two cities. A line of blockhouses defended the rail line, and a blockhouse and rifle pits had been constructed on the cliffs overlooking Fisherman’s Point. A fort on South Toro Cay commanded the narrow channel leading from the outer to inner bay. Caimanera was also protected by a fort, and the Spanish gunboat Sandoval patrolled the inner bay.

Declaring War on Spain: The Blockade Begins

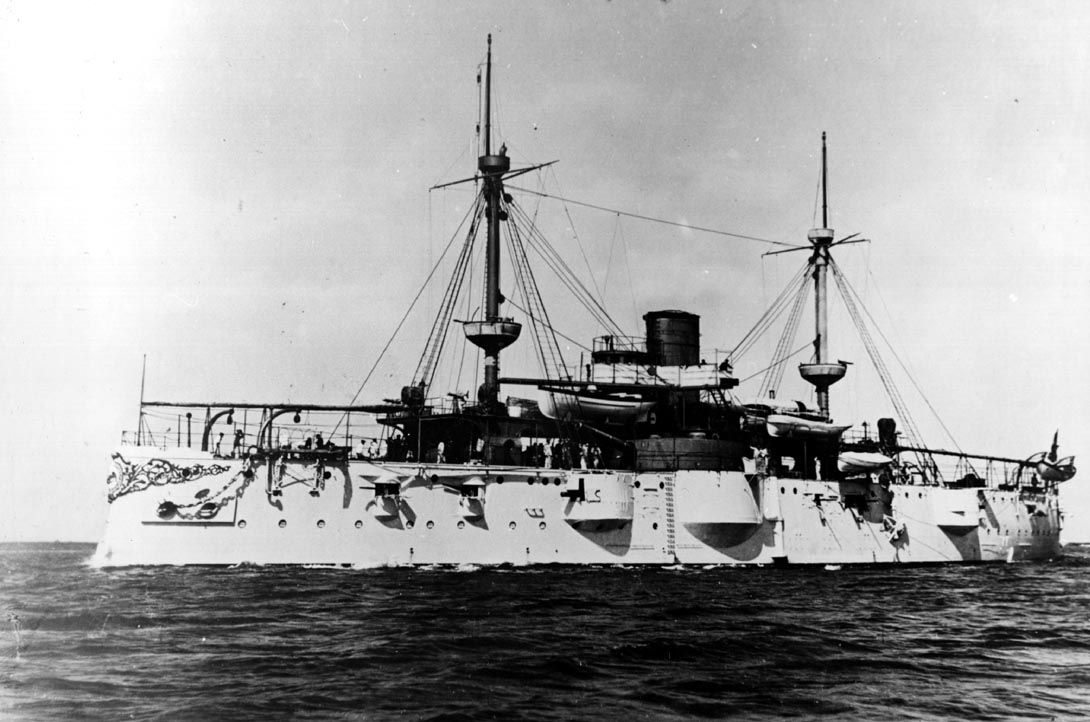

After the sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898—and the subsequent declaration of war by the United States against Spain—a naval blockade of Cuba, under the direction of Adm. William T. Sampson, was put into effect. However, recoaling a hundred blockading ships became an immediate major problem. Only 13 coaling vessels were available to the blockade fleet, and the nearest coaling station was at Key West, Fla., a distance of 90 miles.

Military Eyes Guantànamo As A Coaling Station

A few weeks before war was officially declared, U.S. Navy Secretary John D. Long had visualized Guantànamo Bay as an ideal advance coaling station, and directed the U.S. Marine Corps to organize a battalion for service in Cuba.

On April 6, 1898, Col. Charles Heywood, commandant of the Marine Corps, ordered selected Marines from bases on the East Coast to assemble at the Brooklyn Barracks at the New York Navy Yard.

“Brooklyn Barracks Bustled With Wartime Activity”

A detachment of 60 Marines of D Company, under the command of Capt. William F. Spicer, departed Portsmouth, N.H., by train. Private John H. Clifford was one of the group. In his article, “My Memories of Cuba,” which appeared in the June 1929 issue of Leatherneck magazine, Clifford described the flurry of excitement upon reaching the Navy Yard: “Brooklyn Barracks bustled with wartime activity. Detachments were arriving from everywhere. The barracks were overcrowded and finding a place to sleep was a problem. Eventually a battalion, consisting of five rifle companies and one artillery company was formed. The battalion strength was comprised of 636 enlisted personnel—along with 24 officers—and was placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Huntington.”

The Marine rifle companies were issued Lee straight-pull rifles—a high-velocity, 6mm weapon that used smokeless powder. The artillery company, under Capt. F.H. Harrington—and battery commanders First Lts. C.G. Long and William N. McKelvy—was provided with three-inch rapid-fire guns and the Colt 1895 machine gun.

John Clifford continued: “On April 22, with the Navy Yard Band leading the way, we marched down three Brooklyn streets. Thousands of patriotic, cheering Americans lined the parade route as we headed back to the yard and went aboard the Kanapaha.”

On April 26, the Marine troopship, escorted by the Montgomery, sailed for Key West, Fla. During the voyage, the rifle companies were exercised in volley firing, and the three-inch guns fired one round each. In the late afternoon of the 29th, the Panther anchored at Key West. The Marines disembarked, and for the next month drilled and engaged in gunnery practice.

Marines Prepare For Landing At Guantànamo

About three o’clock on the morning of June 6, the Marines struck their tents, loaded their baggage, and once again marched aboard the Panther. The next day the battalion sailed for Cuba and an amphibious landing at Guantànamo Bay. Before any attack could be launched, however, the telegraph cables connecting Guantànamo with Caimanera and Haiti would have to be cut.

The Marblehead, St. Louis, Yankee, and the cable-steamer Panther were assigned the dangerous task. The flotilla was placed under the command of Cmdr. Bowman McCalla aboard the Marblehead. McCalla had orders to reconnoiter the bay while the St. Louis and Adria cut the cable at its source—Fisherman’s Point.

The cable-cutting went off without a hitch as the Marblehead and Yankee steamed into the bay. McCalla observed Spanish soldiers entrenched on the cliffs and in front of the blockhouse. He immediately ordered his ship and the Yankee to open fire on the enemy position. The blockhouse was swiftly pounded to rubble and most of the trenches destroyed.

During the bombardment, the Marblehead and Yankee were in plain view of the Spanish artillery batteries on South Toro Cay and the Caimanera fort. The Spaniards fired several nuisance salvos, without effect, and at dusk, the St. Louis raced down the channel, fired a few quick shots, then dashed back to Caimanera.

Ships Begin Island Bombardment

Commander McCalla conferred with Admiral Sampson. They decided to land the Marine battalion at Fisherman’s Point and establish a campsite at the clifftop blockhouse.

Preparatory to the invasion, the Marblehead, along with the Dolphin and Vixen, bombarded the landing beach and enemy trenches. They were soon joined by the St. Louis, Yankee, and the Adria. The exact number of Spanish troops in the vicinity was not known; however, about five thousand soldiers, commanded by Gen. Felix Pareja, were reported to be encamped a short distance inland.

Aboard the Marblehead, a war correspondent for the Boston Herald described the amphibious operation: “The first landing of American forces on Cuban soil took place about eight o’clock on the morning of June 10. A detachment of 40 marines from the Oregon and 20 from the Marblehead went ashore at Guantànamo Bay and occupied the east entrance of the harbor below Fisherman’s Point.

Marines Land Unopposed At Guantànamo

“At one o’clock the Panther, escorted by the Yosemite, arrived with more than 600 marines. The men climbed into cutters and were towed by steam-launches to the beach.

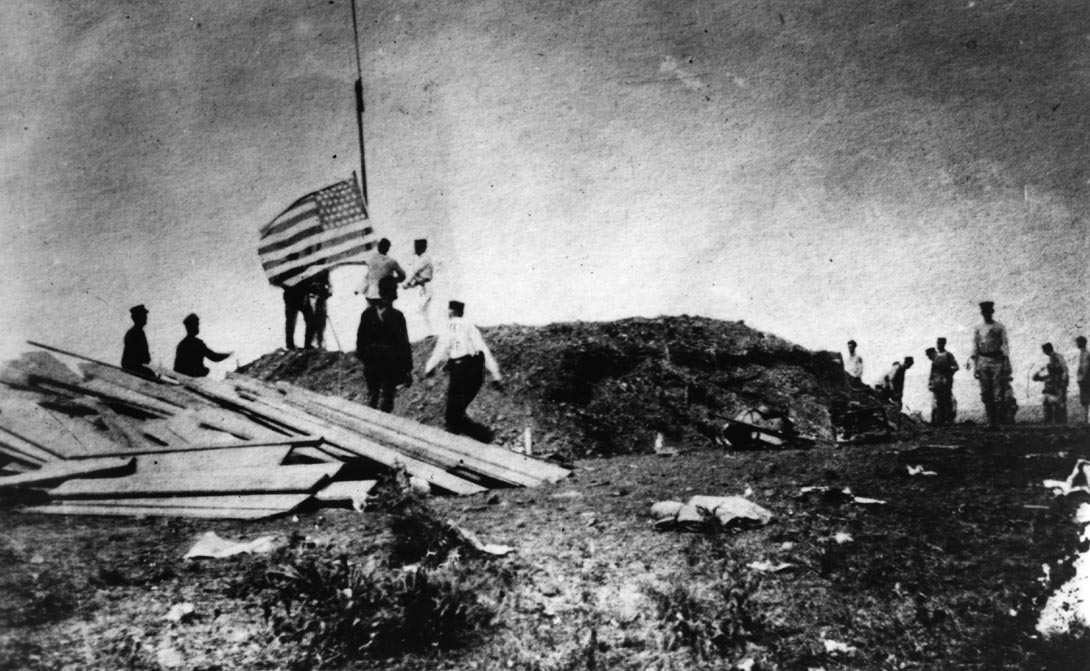

“The landing, carried out under a blazing-hot afternoon sun, was unopposed. B Company, under Lieutenant N.H. Hall, was the first contingent ashore. C Company, led by Captain George F. Elliott, was the next to land, and both companies deployed up the steep cliff to the ruins of the blockhouse.

“The entire assault proceeded as efficiently as a Sunday-school picnic. Within an hour, the marines had burned the village and taken possession of the hill. Color Sergeant Richard Silvey hoisted the Stars and Stripes above the blockhouse—the first American flag to fly over Cuba. The site was enthusiastically given the name of Camp McCalla, after the popular commanding-officer of the Marblehead.”

Vulnearable Camp McCalla

The Spaniards had evidently made a hurried departure from the hill. Scattered about the trenches and blockhouse were many personal possessions—along with hammocks, machetes, ammunition, and two field pieces. Also discovered in the rubble were a batch of official telegrams giving the strength of Spanish fortifications in the area. It was suspected that the messages had been deliberately discarded to deceive the Americans, but they were turned over to Admiral Sampson so he could investigate their authenticity.

In his report to Marine Headquarters, Lt. Col. Huntington commented on the Marine campsite: “The hill occupied by our troops is not a good location—but the best to be had at this time. The ridge slopes downward and to the rear from the bay. The plateau at the top is very small, and the surrounding countryside is covered with thick, almost impenetrable, brush. Our position is commanded by a range of hills about 1200 yards distant.”

With the bay at their backs—and the jungle and hills to the front and sides—the Marines were in an endangered position, but tents were pitched and outposts established. Shortly after sundown the Marines ate their first meal in Cuba—hardtack and coffee.

About 10 o’clock a sentry sounded an alarm. The Marines were rousted from their sleep, and a skirmish line was quickly formed. Spanish voices were heard in the distance and lights were seen in the brush, but no attack materialized.

The Marines had a restless night and awoke to another scorching hot day. The only sounds emanating from the jungle were the cooing of mourning doves—which in reality were the Spaniards signaling to each other.

Two Outpost Duty Privates Killed By Spanish

In the early afternoon, Colonel Laborde, commander of the Cuban insurgents in the area, told Huntington that the main Spanish force in the vicinity was headquartered at a freshwater well at Cuzco—six miles southeast of Fisherman’s Point. The well provided the only drinking water for the enemy troops—which comprised about five hundred soldiers.

Late in the day, Privates William Dumphy and James McColgan of D Company were on outpost duty about three hundred yards from camp. They were relaxing under a tree, but were soon lulled into carelessness by the constant heat and hypnotic sounds of the tropical forest. Suddenly, without any warning, Dumphy and McColgan were attacked and killed by a Spanish patrol that had sneaked unobserved through the thick brush. Both men were shot through the head at close range. The bodies of the Marines were stripped of shoes, hats, and cartridge belts—and then horribly mutilated with machetes.

“They Never Had A Chance To Defend Themselves”

In his handwritten diary, Private Henry D. Schrieder of C Company recalled the events that followed: “About five-thirty we heard shots. Moments later, a Cuban scout rushed into camp shouting that a Spanish force was heading our way. The outposts were immediately alerted and hurried measures were taken for defense of the camp. Enemy Mauser bullets quickly began zipping over our heads. The Spaniards were hiding in the brush on all sides of us. Many had leaves and branches tied around their bodies so that they could scarcely be distinguished from the undergrowth. With our entrenchments still not completed, we made easy targets.

“Colonel Huntington tried to lead the battalion in a counterattack, but the underbrush was so thick and thorny that he continued the advance with only one company. Upon reaching the outpost defended by Dumphy and McColgan, the butchered bodies of our fellow marines were discovered. They never had a chance to defend themselves.”

The search for the elusive enemy was abandoned at dark and Huntington and his frustrated detachment returned to the camp. Throughout the night, the Marines never slept. Deadly, high-velocity bullets riddled their defenses. Furious volleys—interspersed with sporadic fire—kept the battalion on adrenalin-flowing alert.

About one o’clock in the morning, Assistant Surgeon John B. Gibbs was standing in front of a hospital tent. He had just remarked to another doctor, “Let’s get out of this. I don’t want to be killed here!” when a Spanish bullet struck him in the head—passing through one temple and out the other.

Spaniards Launch Several Attacks

Sergeant Charles H. Smith and his squad from D Company were dug in on the east slope of the hill on picket duty. They withstood enemy attacks throughout the night. Smith was killed, and Corporal Glass and Privates McGowan and Dalton were wounded. First Lieutenant W.C. Neville and several men ventured out to recover Smith’s body, but they came under heavy fire and were forced to fall back.

Henry Schrieder continued his account: “The Spaniards launched a dozen attacks before daybreak. The assaults were most threatening after midnight, when it seemed that the camp was completely surrounded. We held our ground defiantly, and our volleys seemed to have been delivered with good judgment, for they sufficed to hold the enemy in check.

“The night was uncommonly dark but the Marblehead, anchored out in the bay, kept her searchlight trained on the thickets. The lightbeams—along with the muzzle flash of Mauser rifles—served to guide our aim.

“Snipers Became A Major Problem”

“At daylight on the 12th, the artillery field pieces, under the command of Lieutenants Long and McKelvy, commenced pounding the Spanish positions with rapid fire barrages. About this time, the Texas arrived and landed 40 marine reinforcements and two Colt machine guns. The weapons were hauled up the hill and mounted on the earthworks. The additional fire power promised more security for our men defending the camp, and gave Colonel Huntington the opportunity to deploy one company as skirmishers and move forward to dislodge the Spaniards. The efforts of the skirmishing party—supported by gunfire from the camp and numerous salvos from the Marblehead—seemed almost continuous, but the Spaniards kept shifting their attacks from place to place.

“Snipers became a major problem. Accordingly, all tents and supplies were moved to the side of the hill facing the bay, and a trench 40 yards long was dug on the south front. A barricade was also constructed as enemy forces were reported to be assembling for an all-out assault on Camp McCalla.

“At ten o’clock on the morning of the 12th, Privates Dumphy and McColgan and Surgeon Gibbs were buried on the south slope of the hill. The solemn ceremony was continually interrupted by the enemy—to whom the sacred purpose of those sharing in this observance must have been apparent. The prayers were concluded under the zing of Mauser bullets. The salutes we fired over the graves were aimed at the Spaniards.”

Following the burial service, a flagpole and a large American flag were sent ashore from the Marblehead. The permanent flag was raised over Camp McCalla by the Marine battalion adjutant, First Lt. Herbert L. Draper. As the Stars and Stripes whipped in the breeze, the Marines cheered and ships in the harbor fired salutes and blew their whistles.

At the conclusion of the flag-raising ceremony, a defense perimeter was established, and C and D Companies took over the outpost positions. Ten Cuban scouts were attached to each picket company.

Repelling the Spanish Charge of Camp

As soon as darkness settled over the jungle, a large Spanish force attacked the outposts. Hearing the gunfire, the Marblehead and Panther closed the shore and sent salvo after salvo into the woods. Several shells exploded in the vicinity of D Company. Word was quickly passed back to camp, and the ships were ordered to cease firing. Commander McCalla assumed responsibility for the error. He stated that upon noticing the muzzle flash from the Marine rifles, he had mistakenly believed that they were Mausers.

For most of the night, the men of D Company were kept busy defending their outpost. Under the circumstances, casualties were light. Sergeant Major Henry Good and Private Goode Taurman were killed, and Privates Burke, Wallace, Martin, and Roxbury were wounded. Just before daybreak, a large Spanish force sneaked through the high brush on the hill and charged Camp McCalla, but was beaten back by heavy rifle and machine-gun fire.

Later in the morning, reinforcements of 50 Cuban insurgents commanded by Lt. Col. Enrique E. Tomas arrived. The Cubans, familiar with guerrilla tactics, deployed in front of the camp—burning the thicket as they advanced—and cleared an area so as to deny the Spaniards the cover they had been using to their advantage.

Weary Marines Thwart Another Attack

Sporadic enemy sniper fire continued to plague the Marines. They stayed by their guns, ready for immediate action. By nightfall, the battalion was on the verge of exhaustion. In addition to the unbearable heat, the Marines had not slept or rested for more than 72 hours.

At daybreak on June 14—while half the Marine battalion was at breakfast—the Spaniards launched a heavy attack on Camp McCalla from the direction of the Cuzco hills. But once again they were beaten back. The Marblehead’s steam-launch, heading for Fisherman’s Point, opened fire on the retreating Spanish troops, chasing them along the beach with her rapid-fire one-pounder.

Taking the Battle To The Spanish

Colonel Huntington realized that his overly-tired Marines could not keep fighting off enemy raids, both day and night, while waiting for promised reinforcements to arrive. A large-scale Spanish assault could possibly drive the battalion off the narrow beachhead. Huntington discussed the situation with Colonel Laborde. The Cuban commander suggested a surprise attack on the Spanish headquarters at Cuzco. Defeat of the enemy troops—and destruction of their water supply—would force the Spaniards to withdraw from the area. A strategy conference was held with Commander McCalla, and the plan was given the go-ahead. It was nine o’clock when the Marines received their orders—and the sun was already hot and bright.

In his official report of the expedition, Captain George Elliott stated: “In accordance with verbal instructions, I left camp with 160 men of C and D companies—commanded respectively by First Lieutenant L.C. Lucas and Captain William F. Spicer. We were accompanied by 50 Cubans under Lieutenant Colonel Enrique Tomas. My orders were to destroy the well at Cuzco. This was the enemy’s only drinking water supply within 12 miles, and made possible the continuance of annoying attacks upon Camp McCalla.

When we were about three miles from Cuzco, I sent the first platoon of C Company, and 25 Cubans under Lieutenant Lucas, to traverse a high hill on the left. I had hoped to cut off any enemy pickets in the vicinity, however, our detachment was seen by a Spanish outpost. The Spaniards immediately ran to warn their main body of soldiers at Cuzco.

“Lucas and his platoon were successful in gaining the crest of the hill, but came under heavy enemy fire from the valley below—a distance of 800 yards. Meanwhile, Second Lieutenant P.M. Bannon led the second platoon of C Company along a path below the crest and hidden from view by the Spaniards. In order to keep from being seen, it soon became necessary for Bannon’s column to leave the narrow trail and proceed through the heavy brush. Captain Spicer and D Company followed in single file.

“We Were Under Attack By An Unseen Enemy”

“The crest of the hill was in the shape of a horseshoe—two-thirds encircling the Cuzco valley and the well. By late morning, C and D Companies, along with the Cubans, had occupied one-half of the horseshoe ridge.

“Meanwhile, Second Lieutenant L.J. Magill—on outpost duty with a platoon of A Company—heard the firing and came to our assistance. His detachment was directed to cover the left-center of the ridge.

“We were under attack by an unseen enemy. Individual Spaniards were sighted here and there and fired upon. They would dash from cover to cover, enabling us to find targets, which otherwise was impossible because of the thick chaparral in which the Spanish soldiers successfully concealed themselves.

“The enemy, rushing from one position to another, gave Magill’s platoon the opportunity to catch the Spaniards in a crossfire. The Spanish defense was quickly reduced to straggling shots.

“The Dolphin, which had been ordered to cruise along the shore and support us if necessary, was signaled to destroy the house used as the enemy’s headquarters, and also to bombard the valley.”

Spanish Headquarters Destroyed

By this time, however, the ship had steamed too far up the coast and her shells began falling on Magill’s position, forcing the platoon to dig in on the reverse side of the ridge. Sergeant John H. Quick jumped to his feet and—amid a barrage of Mauser bullets—signaled the Dolphin to cease firing.

Lieutenant Magill was ordered to form a skirmish line and move down into the valley toward the sea. Lieutenant Lucas, with 40 men, fought his way into Cuzco, destroyed the well, and burned the building being used by the Spaniards as their headquarters.

Magill’s platoon ransacked the enemy’s shore signal station and confiscated a heliograph signal outfit that had been in constant use since the Marine landing.

Spanish Retreat With Loss Of Fresh Water

The mission was a resounding success. Eighteen Spanish soldiers, including one officer, were captured—along with 30 Mauser rifles and a large quantity of ammunition. For the Americans, casualties were remarkably low—one Marine wounded and 12 overcome by the heat. Spanish losses were approximately 30 killed and 150 wounded. The fight at Cuzco was the first pitched battle between American and Spanish troops during the war. With their fresh-water supply cut off, the Spaniards retreated to Caimanera and the town of Guantànamo.

Striking the Spanish at Caimanera

On June 15, Captain John Philip, commanding the Texas, received orders to bombard the fort at Caimanera and drive out the Spaniards. The Texas, followed by the Marblehead, carefully steamed past the Toro Cays and entered the inner harbor. Captain Philip maneuvered the battleship as close to the shore as possible without running aground, and opened fire with his 12-inch battery. The Marblehead joined in the action—the blasts from its five-inchers drowned out by the thunder from the big guns of the Texas. The Suwanee took position off the starboard side of the Marblehead and participated in the attack.

Carlton T. Chapman, a war correspondent aboard the press boat Kanapaha, described the bombardment in vivid detail: “The St. Paul and other vessels remained in the lower bay. Sailors crowded the rigging and swarmed every lofty perch. They had grandstand seats and could see it all—the ships, the red-tile roofs of Caimanera, and the fort where exploding shells hurled thick clouds of yellow dust skyward.

“The marines on McCalla Hill had even a better view. A dark blue thundercloud in the background made a magnificent setting for the ships and the spiraling smoke which floated across the bay and melted into the distance.

The Texas’s Strikes Go Unanswered

“The sailors and marines cheered, shouted and waved their hats whenever a shell from the Texas struck the fort. The flash of the discharge and the resulting explosion seem to be instantaneous. Then comes the smoke from the guns—rolling and swelling out in a vast cloud—followed by shock waves from the explosions reverberating across the water and ringing in your ears.

“The battleship was silhouetted most of the time—standing out in bold relief against the flame and smoke one moment, and enveloped in a thick cloud of haze the next. Except for a few shots from the fort at the opening of the action, there was no reply from the Spaniards, The bombardment was halted after an hour and a quarter and the fighting men-of-war withdrew down the bay.”

The Marblehead’s launch remained in the channel and began grappling for mines. The boat’s crew had no sooner hooked one of the deadly devices when enemy soldiers along the shore opened fire on the sailors. The launch was struck several times, but the bow gunner turned his one-pounder on the Spaniards and the other members of the crew replied with their rifles. The battle was running hot and heavy. Suddenly the boat’s gun mounting loosened and the one-pounder fell overboard.

Spanish Soldiers Surrender At Camp McCalla

The Suwanee, hearing the shooting, dashed up the channel and shelled the enemy positions, driving the Spanish troops into the jungle. Henry Schrieder remarked: “Two mines were picked up by the Marblehead’sAdria launch. Both were French-made and packed with about a hundred pounds of guncotton each. The mines were manufactured in 1896 and placed in position when war was declared.

“Two Spanish soldiers came into camp and surrendered. They reported that their forces near Camp McCalla had been without food for three days, and one body of 500 men would give themselves up if not prevented by the officers.

“Spanish snipers in the bushes and trees along the north shore of the bay continue to be a nuisance. At dark, searchlight beams from the ships shined up and down the channel and into the thickets looking for any movement. About ten o’clock, the Marblehead, Suwanee, Dolphin and St. Paul steamed up the bay and bombarded the enemy shoreline for a half-hour.”

The following morning, June 16, the Oregon arrived escorting two large coal colliers. Captain Charles Clark, commanding officer of the Oregon, requested permission for his men to get in some target practice. The request was granted and, in the early afternoon, the Oregon fired a few salvos into Caimanera—hitting the telegraph office and railroad station. As soon as the first shell exploded, a train standing alongside the station immediately put on a full head of steam and took off up the tracks with its whistle shrieking.

Huntington Targets Remaining Resistance

A few days after the bombardment of Caimanera, Commander McCalla began to concentrate his efforts on clearing the enemy minefield, which still posed a danger to ships. A minesweeping operation was carried out using two steam-launches and two whaleboats from the Marblehead and Dolphin—but they were quickly fired upon by a detachment of Spanish infantry across from the Toro Cays. McCalla was determined to eliminate the danger, and an expedition was planned.

At three o’clock on the morning of June 25, Colonel Huntington left camp with C and E Companies, along with 60 Cubans under Lt. Col. Tomas. Their mission was to clean out Spanish resistance on the west side of the bay.

The Marines crossed the channel in 15 boats. Henry Schrieder narrated: “The Marblehead took position close to the beach to cover the landing. The boats advanced in three columns and the marines were landed quietly and rapidly. A thorough reconnaissance was made, but the enemy was gone. Evidence indicated that they had left in a great hurry—probably the night before. We reembarked at nine o’clock. A column of Spaniards was seen from the Marblehead—one or two men at a time crossing a dry lagoon a few miles to the northwest. They were not fired upon.”

Meanwhile, around June 22 to June 25, an American expeditionary force of about 16,000 men had landed east of Santiago without opposition. A week later, the historic battles of El Caney and San Juan Heights ended in victory for U.S. forces, and opened up the approaches to Santiago itself.

Santiago Surrenders; Peace Deal Signed

On the morning of July 3, a demand was sent to the city’s commander, Arsenio Linares, to surrender the town or suffer bombardment. After several days of negotiations, Linares surrendered the city on July 15.

Less than a week after the surrender of Santiago, Guantànamo Bay was used as a staging area for the invasion of Puerto Rico. This was the last important episode for Guantànamo Bay in the Spanish-American War. The conflict ended on August 12, 1898, with the signing of the peace protocol and an armistice.

The American base at Guantànamo Bay was not formalized by lease agreement between the United States and Cuba until five years later, when in 1903 it was acquired as a coaling and naval station.

In 1903, George F. Elliott was appointed Brigadier General Commandant of the Marine Corps, relieving Maj. Gen. Charles Heywood. Elliott was the only commandant to receive his early training at West Point, and retired with the rank of major general in 1910.

Originally Published August 4, 2015

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments