by Frederick Grant

On December 25, 1065, King Edward the Confessor presided over a spectacular Christmas banquet at his palace on Thorney Island in the Thames River, just two miles upstream from London. The king was an old man, white bearded and frail, but the magnificence of his robes and glitter of his crown hid his real condition from the casual observer.

The king was dying, and the court knew it. Since November he had had a series of “brain maladies,” possibly cerebral hemorrhages or strokes, and did not have long to live. Edward used up his last remaining reserves of strength in the Christmas festivities; the very next day he took to his bed, never again to leave it.

He had earned the sobriquet “the Confessor” because of his piety and overall saintliness. He attended to government business when he had to, but much preferred prayers and contemplation to the affairs of this world. The Confessor’s main goal in life was to build a monastery dedicated to St. Peter on Thorney Island. He devoted long hours to this project and had a palace built nearby so he could watch the abbey’s construction progress. The abbey church, or “Minister,” was to the west of London, so people later started calling it “Westminster Abbey.”

He had earned the sobriquet “the Confessor” because of his piety and overall saintliness. He attended to government business when he had to, but much preferred prayers and contemplation to the affairs of this world. The Confessor’s main goal in life was to build a monastery dedicated to St. Peter on Thorney Island. He devoted long hours to this project and had a palace built nearby so he could watch the abbey’s construction progress. The abbey church, or “Minister,” was to the west of London, so people later started calling it “Westminster Abbey.”

Edward longed to see the consecration of his new abbey church, and perhaps it was this that kept him alive those last few weeks. On December 28, 1065, the church was consecrated, and though Edward was too ill to attend the ceremony, he could now die in peace.

“Do Not Mourn for Me”

By early January 1066, the king was failing fast, and all knew it was just a matter of time. Edward suffered periods of delirium, and at times he lapsed into a coma. On January 4, the king regained consciousness and remarked to the entourage, “Do not mourn for me, but pray God for my soul and leave me go to him.” Edward was longing for the next world, but his subjects still had to live in this one. Who was going to take his place as king? Unfortunately, Edward had taken a vow of chastity just prior to marriage, a move not likely to produce any heirs. His wife was more like his sister, and this childless union was about to bear bitter fruit.

The dying monarch offered his hand to Harold, Earl of Wessex, one of the most powerful magnates in the realm, and told him to protect the kingdom. With this

gesture, Edward the Confessor made his choice for the next king of England. His earthy duty done, the Confessor died January 5, 1066.

But the succession was not as clear-cut as it seemed. In Anglo-Saxon England it was the Witan, an assembly of notables, who chose a successor when a king died. The Witan was a rather amorphous body of royal councilors that included nobles and high churchmen. Custom dictated that it was they, not the king, who chose England’s next ruler, though of course a king’s wishes would carry great weight.

Choosing the Next Candidate for the English Throne

But the Witan had to carefully consider its course. Harold Godwinson had been endorsed by the king on his deathbed, but there were other factors in favor of the earl. In the old king’s declining years Harold had been the virtual ruler of England and all but acknowledged heir apparent, at least in some people’s minds. Even when the Confessor was alive Harold was given near-royal status with the titles Dux Anglorum, “Duke of the English,” and subregulus, “subking.”

Harold had no royal blood, but he wielded power effectively, which was almost as good. Before long some descriptions of him proclaimed him Dei Gratia Dux, “Duke by the grace of God.” By implication, even the Almighty was endorsing his rule; now, all that was needed was selection by the Witan to make it official.

There were other candidates for the English throne, but the Witan had good reason to dismiss their claims. There was Edgar, great-grandson of an earlier English king, but the lad was only 13 and perilous times demanded maturity on the throne. Swen of Denmark and Harold Hardrada (“hard ruler”) of Norway might be possibilities, but foreign “imports” were not to the Witan’s taste. Finally there was William, Duke of Normandy, whose territory was just across the channel in France.

William was (probably) born in September 1027, natural son of Robert I of Normandy and a tanner’s daughter named Arlette. Before 1066 William was called “the Bastard,” but the stain of illegitimacy was no barrier to his advancement. He succeeded his father when he was about eight years of age, and by 20 was a tough and experienced soldier and able administrator. Some claim he was sensitive about his illegitimate birth, but the early Middle Ages were a rough, bloody era that cared little about a man’s origins if he proved his worth. It may be that his mother’s humble origins, not her lack of a wedding ring, made William touchy. When he besieged the town of Alençon, its citizens covered the walls with hides to protect them from Norman fire. The Duke took this as a personal insult—a reminder that his maternal grandfather had been a humble tanner. After taking the city he had the offending citizens’ feet chopped off. His enemies’ suggestion that he “stank like a tannery” would also induce a blinding rage.

In 1066 Duke William of Normandy was 38 years old and in the prime of his life. He would become grossly fat in later life, but now he was tall (about five-foot-ten), muscular and agile, with a fist “that could fell an ox.” Normandy was a fractious, turbulent place, where unscrupulous nobles and their retainers were always on the verge of revolt, lusting for power and not afraid to kill to achieve their selfish ends. In the early years of William’s rule petty warfare was endemic, bloodshed and rapine commonplace. William restored order to his rebellious domain by being even more ruthless than his vassals. He achieved a well-deserved reputation for cruelty, and it was said his “eye could quell the fiercest baron.”

Duke William Claims the Crown Should Be His

In terms of heredity, William’s claim to the English throne was weak. Putting aside his illegitimate birth, his great-aunt Emma had married two English kings and had been Edward the Confessor’s mother—hardly a ringing endorsement for the crown. William was unscrupulous, but he also had his own sense of rough justice. He claimed the English throne because he felt Edward the Confessor had promised it to him. Never mind the fact that the Witan was the real “power behind the throne” when it came to the succession—William felt the crown was his.

These feelings were substantially reinforced by a curious event that remains mired in controversy to this day. It seems that in 1064 the then-Earl of Wessex had sworn an oath of fealty to William, in essence pledging to support his claims to the English throne. An oath was a sacred thing in the Middle Ages, something not to be taken lightly.

Norman influence in England did not suddenly begin in 1066. Edward the Confessor was half Norman and had lived in exile in Normandy for a number of years. Norman architecture was beginning to be seen in England around this time. More important, Edward surrounded himself with Norman friends and gave English estates to Norman nobles.

Seen against this backdrop, it’s entirely possible that Edward the Confessor had promised the English throne to Edward on some occasion. It was said that the Confessor chose William during the latter’s visit to London in 1051. Scholars now believe the visit was a myth, but apparently the king sent William some kind of pledge.

In any event, the Witan chose Harold as the new king the day after Edward’s death. As we have seen, Harold was already ruler in all but name, and though he did not have a drop of royal blood he had already proven himself. He was also native-born and a mature adult in his forties, not a stripling youth like Edgar.

Harold Godwinson Crowned the Day Edward Is Buried

Edward the Confessor was buried in his beloved Westminster Abbey and Harold was formally proclaimed king that same afternoon. Harold accepted the crown with apparently few qualms and was duly invested with the tokens of royalty. A crown was placed upon his head, a sword of protection girded around his waist, and a scepter of virtue and rod of equity placed in his hands. He was soon to be weighed down by his broken oath to William, a political albatross around his neck heavier than any robe of state.

How could this have come about? How could a man like Harold, who obviously had a desire to rule England, blithely give his allegiance to William of Normandy? The circumstances surrounding his oath to William have been obscured by the passage of time and partisan politics. Medieval chroniclers sometimes slanted the facts to conform to their own prejudices, and Norman scribes rarely gave Harold the benefit of the doubt.

As far as anyone can tell, the story of Harold’s oath began in the summer of 1064.

Some Norman chroniclers maintain Harold had been dispatched to Normandy as the Confessor’s special emissary. Harold was supposed to deliver a message that confirmed William’s right to the English throne, though he might have been on a diplomatic mission of an entirely different nature. Still others claim Harold was merely on an excursion, a hunting or fishing expedition that went awry.

How Harold Came to Pledge Oath of Fealty to William

Whatever the case, Harold’s ship fell afoul of the English Channel’s unpredictable weather and he was soon blown off course. He had the singular misfortune of landing in the territory of Count Guy of Ponthieu, a rapacious noble who thought he could hold Harold for a large ransom. The unfortunate Harold was “bound hand and foot” and cast into a dungeon. Luckily for Harold, Guy was William’s vassal, and the Duke of Normandy quickly secured his release. Harold stayed with William for a while, and the two men found they were kindred spirits. They hunted together and Harold even accompanied William on a military expedition.

It was during this “honeymoon” period that Harold apparently swore an oath of fealty to William, thus pledging his support of the Norman as future King of England. And talk about “under the table” dealings: Unbeknown to Harold, William had placed some holy saints’ relics underneath the table where the oath was being taken. The presence of such relics made the pledge particularly sacred and binding.

Now, only a year and a half after these controversial events, Harold was King of England. In William’s eyes he had broken his pledge and betrayed the Norman’s friendship.

William felt betrayed, and there was only one way to erase the affront: Invade England and take by force what should have been his by right.

In April 1066 a strange sight appeared in the night sky that seemed to portend disaster. A bright smear of light was trailing across the inky void, a fearful apparition that some monks called a “long-haired star” or cometa. Later ages would call it Halley’s comet, but in 1066 the phenomenon produced more fear than wonder. It seemed to presage disaster and was seen by most people as an omen of evil tidings. But where and on whom would the disaster fall?

Fighting Two Fires with a Single Bucket of Water

Harold must have seen the comet, but his immediate concerns were more down to earth. William of Normandy was probably going to invade England, and the new king had to make the necessary preparations. But a new threat loomed in another quarter: Harold’s own disaffected brother Tostig had allied with the Norwegian king Harold Hardrada, and it looked as if they were going to launch their own separate invasion. The English king was like a man trying to fight two fires with a single bucket of water—which conflagration posed the greatest threat?

The first step was to marshal his forces and raise an army, no easy task when standing armies were nonexistent and truly professional soldiers were few. The Anglo-Saxon army had two major components: The fyrd and the housecarls. The fyrd was the militia, basically a levy of peasants. These included ceorls, freemen farmers who had rights as well as duties, and one must not picture them as downtrodden slaves of the soil. Although the plow and not the sword was their natural “weapon,” they probably did have some rudimentary military training.

The other fighting body in Anglo-Saxon England was the housecarls. There’s some ambiguity about the nature of these men; traditionally they were thought of as professional soldiers or well-trained bodyguards. Recent scholarship suggests they were interchangeable with thegns, land-owning nobles with a degree of wealth and status. In any event, these housecarls were well trained and equipped, ready to serve at a moment’s notice when the king gave the word.

Harold also assembled a powerful fleet of ships to contest William’s passage of the English Channel. Through much of the summer Harold had his fyrd levies stationed along the threatened coastlines of Sussex and Kent, and had a fleet positioned at the Isle of Wight.

The weeks passed, and William did not come. The fyrd could only be called out for 40 days, and in any case the peasant levies would have to return home to reap the all-important harvest. If the grain wasn’t harvested, meat salted down, and wool woven, England might face a winter famine every bit as bad as foreign invasion, and perhaps a good deal worse.

King Harold Gives Demobilization Orders

After weeks of waiting in vain, King Harold had no choice but to allow the fyrd to disband and the fleet to disperse. The demobilization orders were given on the Nativity of St. Mary, September 8, 1066. Once winter came, England was safe from invasion until the next spring. But there was still enough time for an invasion, and William’s fleet had been delayed by contrary winds.

Just as the demobilization started a courier brought Harold disturbing news: An enemy force had landed on English shores. The invaders were not Normans but a large force of Norsemen under the command of Harold Hardrada of Norway. This was not a mere raiding expedition for plunder, but a serious bid for the English throne. In fact, Harold of England’s own rebel brother Tostig was with the Norse invaders in the capacity of ally and adviser.

There was not a moment to lose. King Harold gathered what forces he could on such short notice and marched—or rather, rode—to the vicinity of York, roughly two hundred miles north of London. King Harold met the Norse host at Stamford Bridge on September 25 and utterly defeated them. Thousands of Norsemen were slaughtered in the rout, including Harold Hardrada. The English were not in a forgiving mood; earlier the Norsemen had sacked and burned Scarborough, and now it was time to wreak a terrible revenge. Tostig had also perished in the battle, so Harold would never again have to deal with his sibling’s treacherous plots.

Stamford Bridge was a great victory, and the English celebrated in York for several days. The revelry was cut short by disturbing news: William of Normandy had landed at Pevensey. Harold hurried back to London with his men and stayed in the capital for a few days to gather additional forces.

Forests Ring with Sound of Chopping Axes

That William landed at all was something of a miracle. The Normans may have had Viking roots, but they had largely forgotten the seafaring ways of their ancestors. True, sailors could be recruited, and ships could be gathered or built from scratch, but the process was time consuming. Soon Norman oak forests rang with the sounds of chopping axes as trees were felled to build ships. Shipwrights took hammer and adz to shape the raw wood into planks, and before long William had a substantial fleet at the mouth of the Dives River for his great enterprise.

The number of ships needed depended upon the size of William’s army. Medieval chroniclers had a tendency to inflate statistics, and modern estimates are at best educated guesses. One authority reckons William’s fleet at some 450 ships—enough to carry 10,000 men and 3,000 horses across the channel. As previously noted, an adverse wind delayed the expedition for a month, but a westerly breeze finally came up that let William sail to St. Valery, at the mouth of the Somme. Here the English Channel narrows, so England is that much nearer.

Once again, unfavorable winds stalled the expedition, and William found himself bottled up at St. Valery. Actually, the delays were a blessing in disguise, since the long wait caused Harold to partly demobilize his army and disband his fleet. The Pope himself supported William’s quest for the English crown, and the Norman proudly displayed a Papal banner for all to see. In Norman eyes this was a good omen; God would not abandon William’s cause. Sure enough, the winds turned favorable and the Norman fleet set sail for England. William led the way in his flagship Mora, a large lantern hanging from its mast as a beacon for the other ships.

When the Normans landed at Pevensey, they were pleasantly surprised to find no English opposition. William made a brief reconnaissance then ordered a march inland. The invaders pillaged the countryside, stripping the area of food like a swarm of hungry locusts. Towns and villages were laid waste, their inhabitants put to the sword or made refugees. William and his contemporaries had few scruples about such methods; it was simply part of war.

King Makes Controversial Decision To Fight William Immediately

About this time Harold made a decision that would change the course of English history: He would fight William immediately. This decision—seen with the advantage of hindsight—remains controversial. To this day scholars endlessly debate the issue. William was ravishing Sussex, Harold’s original power base, and maybe that warped the English king’s judgment. Or perhaps the victory at Stamford Bridge had made him overconfident. If medieval contemporaries could not fathom his motives, how can we do it 900 years later?

Certainly there’s much to be said for the tactic of waiting. Harold’s army had been bloodied and the men were exhausted. According to some estimates, when Harold marched to Hastings “not one half of his [potential] army had assembled,” though fresh soldiers were coming in all the time.

Leaving London on October 11, Harold and his long-suffering army marched the 60 miles to Hastings in about two days. They made camp and, according to some sources, spent the night “drinking and singing.” If the stories are true, many probably eschewed such noisy bravado in favor of catching a few winks of much-needed sleep. They were going to need it, because the battle would begin on the morrow.

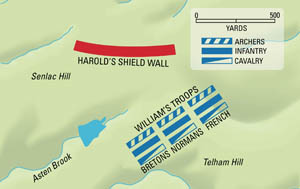

King Harold was going to fight a defensive battle, a wise choice because of William’s mounted knights. The Anglo-Saxons used horses for transportation, not pitched battle, and a man on foot can be at a disadvantage when fighting a mounted opponent. Harold deployed his men on the high ground of a cross ridge that straddled the only road out of a narrow peninsula. The flanks of the ridge are protected by steep valleys, and the position is fronted by the marshy Valley of Senlac, a corruption of the Anglo-Saxon Santlache or “Sand Lake.”

England’s Fate Hangs in the Balance

Saturday, October 14, 1066 dawned, and England’s fate hung in the balance. Each side had about seven thousand men, so they were equal in numbers. Harold placed his men in a shield wall position, shoulder to shoulder, shield edge to shield edge, an unbroken line some six hundred yards long. The shield wall was not only long, but deep. Some sources say the wall was six men deep, some 10–12 men deep. In any case, the housecarls were probably in the front ranks, the lesser trained fyrd peasants in the rear.

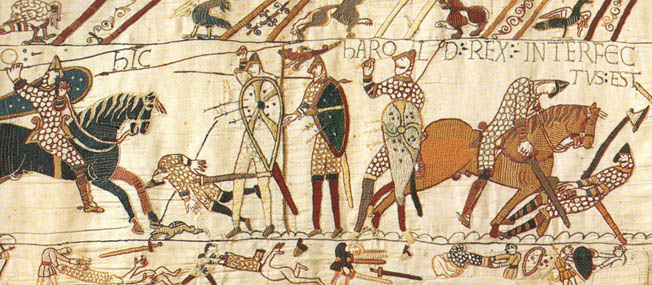

Many of Harold’s housecarls had coats of mail and helmets, but probably men in the poorer fyrd levies had much less protection, maybe a leather jerkin with metal pieces sewn on for added strength. The Bayeux Tapestry shows most English troops in full mail, but these coats were very expensive and surely beyond the reach of the poorer farmers. Harold’s men had spears, swords, and battle axes as weapons. Two types were in use at the time, the two-handed axe and a short axe called a “seaxe” or “sax.” When wielded in the hands of an expert, these axes could produce horrifying wounds in a matter of seconds.

Across the Valley of Senlac, William of Normandy and his army readied themselves for battle. The Duke’s army was arrayed in three divisions, each with archers, infantry and cavalry. The right division was composed of Flemish and French troops under the command of Count Eustace of Boulogne, while the left had Bretons led by Count Alan Fergant. The center was largely Norman infantry and cavalry under William’s half-brother Bishop Odo of Bayeux. Odo, who later commissioned the famed Bayeux Tapestry, seemed to prefer club to cross and fought as hard as any secular knight. Each division had a “layered” formation of archers in the front ranks, then infantry, and finally mounted knights.

“Irresistible First Shock” of Mounted Norman Knights

The backbone of William’s host was the mounted Norman knight. Each knight wore a coat of mail or hauberk, which extended to his knees and was split in the middle for greater ease of riding. The hauberk sleeves ended at the elbow; only great lords like William would have additional protection such as mailed gloves. A knight’s head was protected by a mailed hood called a coif and a helmet. The nasal, a little metal projection in the front of the helmet, afforded some minimal protection to the face.

Norman weapons included a sword, lance, and possibly a club or mace. But a list of weapons had to include the horse, because horse and rider made a formidable fighting machine capable of shock action. A century or so before Hastings the stirrup had been adopted, giving the knight a better seat on his mount. A line of mailed knights charging at a full gallop was an awesome spectacle indeed. Only a few years after Hastings, during the First Crusade, a Byzantine princess witnessed a charge by mounted knights and was impressed. She spoke of an “irresistible first shock” and added that a knight “with lance in his hand could punch a hole in the walls of Babylon.”

The battle began at 9 am. King Harold marked his position by flying two standards: The Dragon of Wessex, which some describe as a royal standard, and his own personal banner emblazoned with jewels and the image of a fighting man. It was said the Normans spotted these standards and so knew the English king was commanding in person. When William learned his great adversary was just across the valley, he swore that if victorious he would build an abbey on the battle site, its altar positioned where Harold’s standards flew.

Norman Archers Attack after the Beginning Fanfare of Trumpets

A fanfare of trumpets from both sides announced the beginning of the battle. The last brassy note had hardly echoed across the morning stillness before elements of William’s army was on the move. The first attack was by Norman archers, who advanced to about 50 paces from the English lines before unleashing a cloud of arrows. Few if any of the lethal shafts found their mark; the bowmen were shooting uphill, and the shield wall was proving a very effective barrier. Feathered shafts pincushioned English shields, but little damage was done.

The bowmen made little impression on the English line, so William sent his mailed infantry forward to see what they could do. The infantry advanced at a brisk pace, the battle cry of “God’s Help!” shouted in Norman French to bolster their fighting spirit. But before they could close with the shield wall, the English unleashed a barrage of missiles that stalled the Normans in their tracks. All sorts of weapons were cast at the oncoming foe—lances and javelins streaked down, and throwing axes somersaulted through the air. It was said that even stones tied to sticks pelted down on the Norman infantry, the latter possibly weapons from the poorer members of the English fyrd.

Norman soldiers crumpled to the ground clutching the missiles that impaled them, and rear ranks had to stumble over the inert or writhing bodies of fallen comrades. The infantry attack was failing, so William sent in his mounted knights for support. The mailed Norman knights spurred their horses forward, some holding their lances overarm and others in a couched fashion. Onward they galloped, the thunderous tattoo of flailing hooves mixing with the clash of arms and the screams of the wounded.

Sheer Butchery of Battle Rages On

The knights reached the shield wall, but a “hedgehog” of English spears prevented the knights from coming too close. The shield wall would part in spots, just enough for English axemen to step out and engage the knights. The fighting was sheer butchery. Swinging English axes came down with force, biting deeply with a sickening thud into legs, thighs, chests— whatever part of the body was exposed. The axemen knew their business, and Norman arms were lopped off at a single stoke in a spray of crimson. Norman horses, too, were vulnerable, and the axemen killed or crippled as many mounts as they could.

The Normans had never fought such foes, but the English axemen had never engaged mounted knights, either. The knights were also skilled soldiers; a well-placed sword-stroke could decapitate a man, the headless trunk gouting streams of arterial blood before collapsing in the mire. The contest raged for a long time, but finally the tide seemed to turn against William’s army. The Bretons on the Norman left broke, and most historians feel this headlong retreat was real, not a ruse. Scenting victory, the English right began to pursue the fleeing Bretons, who by this time were literally bogging down in marshy soil.

Panic can be infectious, and before long the rest of William’s army was showing signs of the “contagion.” The Norman center and right began to waver; the knights who were still fighting at the shield wall turned tail and began to go down the slopes. The Normans were now in serious disorder, and some of them were genuinely panic-stricken. It was time for Harold to order a general advance while the Normans were still off balance. An all-out attack might rout William and clinch a decisive victory. The English would be running downhill, and even had the advantage of momentum.

Why didn’t Harold order a counterattack? Some historians speculate—and that’s all it can be, speculation—that Harold’s army was just too big to be effectively commanded on foot. Harold was on foot at his command post and possibly out of touch with what was going on in the flanks. Other historians have opined that Harold was gripped with a terrible fatalism that October day, passively waiting for God to determine his fate. By contrast William took an active role in the battle, commanding, exhorting, and galloping to threatened points.

“Look at Me Well! I Am Still Alive!”

The Normans were so confused a rumor circulated that William himself had been slain. This was a rumor that had to be nipped in the bud at once, or all was lost. William was more than just a battlefield commander; he was the Duke of Normandy and the heart of the Norman cause. His death would be a calamity of epic proportions, since the Normans would find themselves leaderless and trapped in enemy country.

William rode up to his milling soldiers and raised his helmet enough for his features to be clearly seen. “Look at me well!” William shouted, his rasping voice heard over the din of battle, “I am still alive, and by the grace of God I will yet prove victor.” By acting swiftly William scotched the rumor and restored order to his wavering army. A vulnerable moment had passed, and Harold lost his best chance for victory. In fact, the Normans turned the tables and cut off the soldiers from the English right, the latter still absorbed in chasing the hapless Bretons. These English were dangerously exposed, too far from the main shield wall for their comrades to come to their aid. The Normans surrounded them and hacked them to pieces.

There was now a lull in the battle, a time when both sides rested and regrouped. The battlefield was a place of carnage, a slaughterhouse where blood-daubed bodies and severed limbs lay scattered about, and the grass was trampled and matted with gore. Here and there a wounded soldier probably tried to crawl to safety if he could, but the state of medieval medicine was such that many wounds were invariably fatal.

Sweat-drenched and exhausted, men on both sides probably rested, cleaned bloody weapons, or swallowed a few mouthfuls of bread to assuage their hunger. Accounts vary but the battle was renewed around midday. Once again the Norman knights charged the English line, a tidal wave of steel, chain mail, and horseflesh that crashed against the shield wall dam, foaming and eddying but unable to make a breech.

William Resorts to a “Ruse de Guerre”

The battle raged on, and William decided to resort to a “ruse de guerre,” or trick of war, to overcome the stubborn English. This time, the Normans would purposely retreat, hoping the English would be fooled enough to break ranks and come down the ridge. When the Bretons had retreated, their panic had been real. Now, however, this retreat would be the bait for a well-laid trap.

Unfortunately for the English, the ruse worked not once but twice in succession. Norman knights would fight furiously at the shield wall, then break off the attack in seeming fright or discouragement. English soldiers would rise to the bait and give chase—only to find that their quarry was not as panic-stricken as they had supposed. By the time they discovered their error, they would be cut off from the main English body and slaughtered in detail. The shield wall still existed, but was being rapidly decimated by the Norman ruses. It’s even possible that the wall was shrinking and was thinner in some places than it had been in the morning.

William of Normandy was a good soldier with a superb sense of timing, and he knew the English line was weakening. To hasten its collapse he ordered his bowmen forward once more—but told them to shoot high in the air so their missiles would take an arching flight.

Such a trajectory would not only get behind the shield wall, it would expose more English to Norman arrows. It was done as he ordered, and cloud after cloud of feathered shafts came down on the English in an unnatural rain. Scores fell dead or wounded with each lethal discharge.

Harold Blinded, Bloodied, and Then Hacked Up

Night was falling, and as twilight approached Harold was struck in the eye with an arrow. The king was wounded but not mortally, and some accounts say he pulled the shaft out of his socket and fought on. Half blinded and face covered with blood, Harold must have been in agony and not able to defend himself well. It is said that the shield wall was breaking up around this time, and some Norman knights managed to reach the king and dispatch him before any of his followers could come to his aid. The Normans hacked Harold to pieces, his body so mutilated it later proved difficult to identify.

Harold’s agony was over, and with his passing the English cause itself was in its death throes. The battered English army disintergrated, and there were few leaders left standing to attempt a final rally. Even Harold’s brothers, Leofwine and Gyrth, who had probably commanded troops on the flanks, were numbered among the slain.

Fleeing English survivors scattered, including some who took refuge in a forest behind the battlefield cross ridge. But there was still fighting spirit in the defeated soldiers; some of the fugitives turned on their Norman pursuers in a nearby ravine and killed them. Because of this mishap the Normans thereafter called the ravine “Malfosse,” or “evil ditch.”

William Gains Kingdom, Crowned on Christmas Day

But a last paroxysm of fighting around Malfosse could not erase William’s great victory. He had not only won a battle, he had gained a kingdom. William was a hard, cruel man but not entirely devoid of finer feelings. Harold’s mutilated, dismembered corpse was identified by his mistress, reverently gathered together, and placed in a purple cloth, the color symbolic of royalty. He was given a decent burial in a gravesite near the sea. In William’s eyes Harold had broken a sacred oath, but perhaps the Norman remembered they had once been friends.

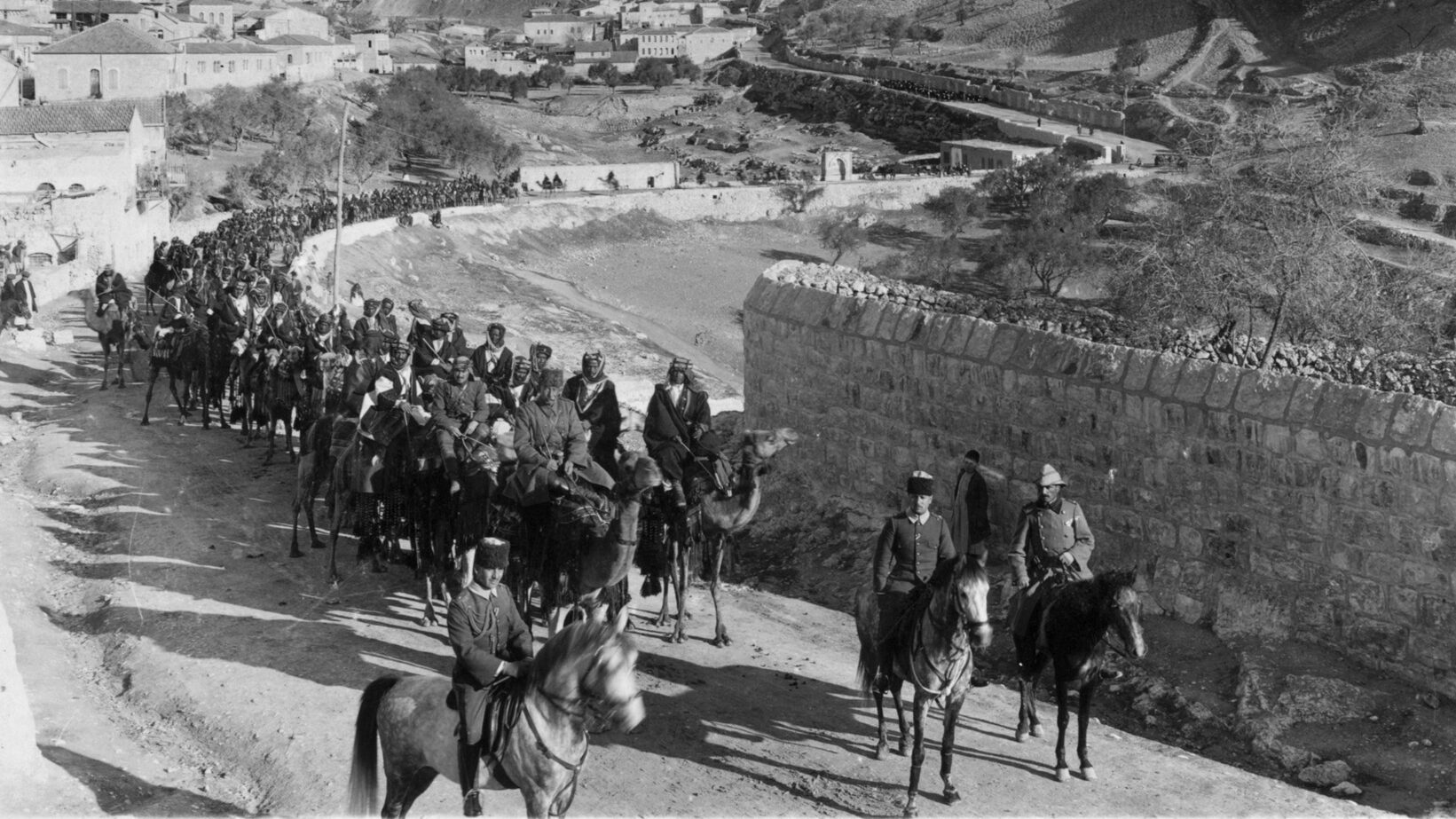

William was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, 1066. Hastings, however, did not end the fighting; Northern England had to be pacified, and there were sporadic revolts that William crushed with characteristic brutality.

The Conquest changed the course of English history. Continental customs such as the feudal system were firmly established. Most important, the Norman victory at Hastings brought England into the medieval European “mainstream.” No longer would the island kingdom be considered a marginal appendage of Scandinavia.

As for William, the stain of illegitimacy—if there ever was one—was washed away by the holy oil of kingly power and majesty. On October 14, 1066, William the Bastard won a new name, a title that still resonates over the centuries. Now he was William the Conqueror.

Originally published August 5, 2015

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments