By VanLoan Naisawald

Darkness had settled over the harbor, the lights along the shoreline casting a faint glow on the murky harbor water. It was almost 9:30 pm, February 15, 1898, and the outline of a large warship—the USS Maine—was clearly visible as she rode at anchor at Buoy No. 4. A few crewmen might have been visible on deck but the ship showed no warlike evidence. Her captain was in his cabin writing a letter. It appeared that it would be just another quiet night. The ship was being hosted on a peaceful state visit, and had been sitting quietly in the harbor since January 25.

Then, with startling suddenness, an immense red, orange, and yellow flash lit the entire harbor. A second or so later a thundering crash and concussion shook everything around. The USS Maine had blown up!

The mystery over the cause of the blast has never been officially solved despite two formal naval boards of inquiry and the passage of over a hundred years. At the time of the tragedy it was immediately assumed by many and much of the press that it had been an act of sabotage by Spaniards or Spanish sympathizers, or even by Cubans trying to provoke the United States into a war with Spain. Indeed, at this moment relations between Spain and the United States were not of the most friendly nature. The United States was in an expansionist attitude, feeling its newfound strength, and also in an altruistic mood, determined to rid Spanish-held Cuba of what was seen as cruel imperialism.

The William Randolph Hearst newspapers had been screaming for action against the Spanish, and the American public had begun to heed. It was an accepted fact that the Spanish had resented America’s more than 30 years of quasi-benevolent and openly expressed sympathy toward the native Cubans revolting against their Spanish colonial masters. But the official position of the U.S. government was one of neutrality and hope for peaceful change. Thus, a friendly visit by a U.S. warship had been scheduled—much against the better judgment of U.S. Consul General Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of Robert E. Lee and former Confederate cavalry leader. But the State Department insisted. Thus the Maine had sailed into Havana harbor at 9:30 am on January 25, 1898, the first friendly U.S. Navy visit to that port in three years.

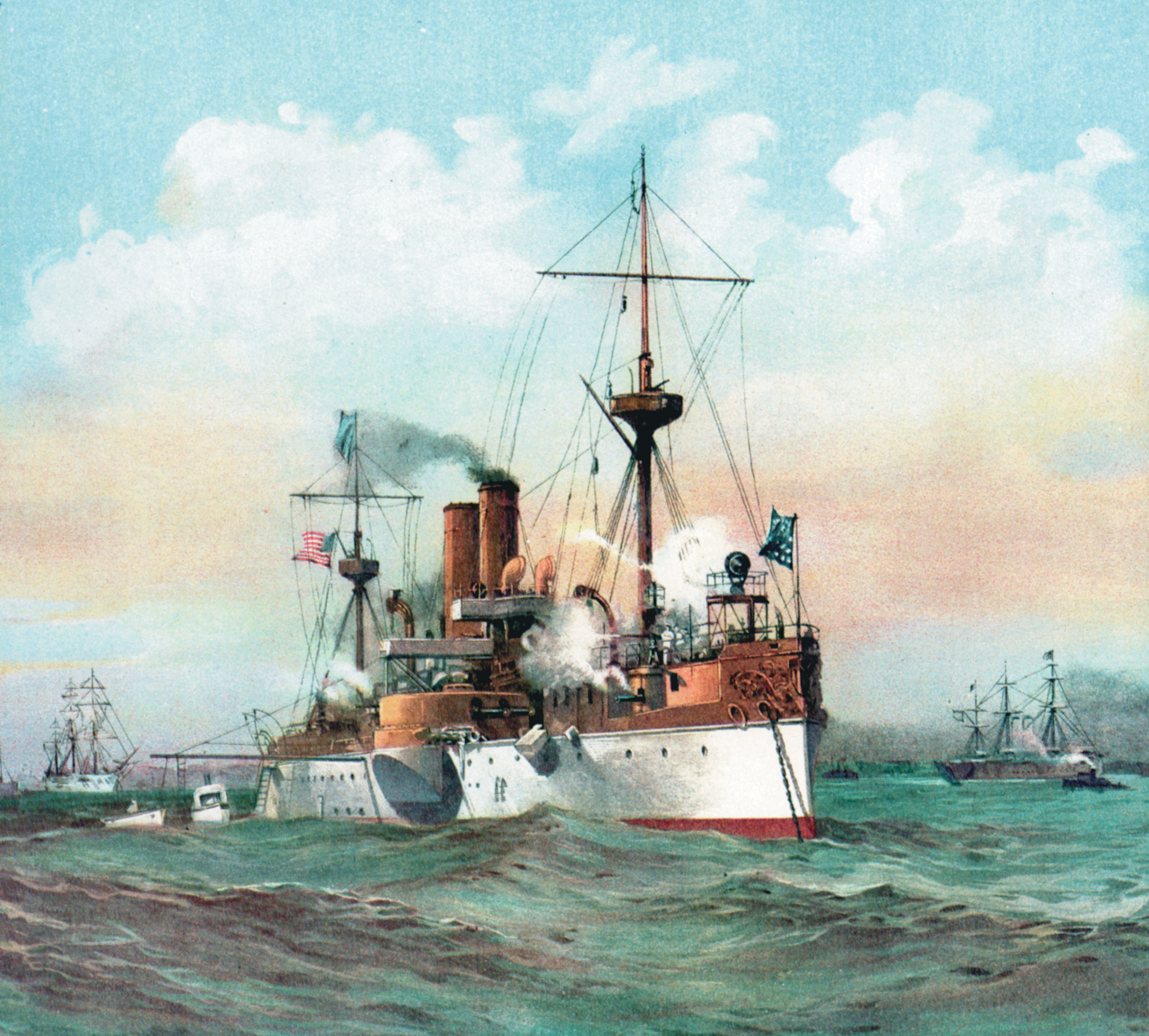

The ship had been a picturesque sight as she sailed slowly past centuries-old Morro Castle at the harbor mouth, her long, white hull and ochre-colored superstructure glistening in the morning sun. The Maine was not originally termed a battleship but an armored cruiser of 6,650 tons. She would later be termed a second-class battleship. But she was a new ship—just three years old—and she was the first U.S. warship designed by naval architects and built in a government shipyard.

Her power was supplied by coal-burning steam engines that turned her two screws for a top speed of some 171/2 knots. Her main armament was four 10-inch guns paired in two turrets, one forward and one aft. But these turrets were placed radically differently—one was offset to port and the other to starboard. The idea was to increase their lateral area of fire. Each turret would have an arc of 180 degrees to its outboard side and a small 64-degree arc to its inboard side. They were not placed amidships as was the conventional method. In addition to her main armament she carried six 6-inch guns and 15 other guns of assorted caliber. An inventory taken the previous June showed her carrying a full ammunition load.

As the Maine approached Havana harbor her captain, Charles D. Sigsbee, unsure of what the reception would be and aware of the possibility—not probability—of hostile acts, still had his ship discreetly prepared for action. However, much of the on-deck gear that would normally be removed if a ship were “cleared for action” remained visible. Crew could easily be seen on her decks in dress uniform and, while her guns were not loaded, ammunition had been passed to the mounts. Outwardly the Maine showed no warlike preparations.

Just outside the harbor a pilot dispatched by the harbor captain was taken aboard. The pilot showed Captain Sigsbee a plot of the harbor. Buoy No. 4 was vacant—Would this be acceptable? Sigsbee replied that it would. He later testified that the actual position of Buoy No. 4 differed from that shown him on the plot but he had not been alarmed by this—such a shifting could have occurred for perfectly innocent reasons. Sigsbee then asked the pilot if the Maine had been expected; no, she had not, came the reply. However, it would later be learned that Consul General Lee had advised the authorities that she was arriving on the evening of January 24.

In any event, the Maine anchored at about 10 am, for the last time, at Buoy No. 4, 400 yards off the Machina Wharf and the vicinity of the Customs and Court Houses. As the American ship secured her lines her officers and seamen on deck no doubt noticed a large Spanish warship some 250 yards northwest of the Maine and a German ship—the Gneisenau—some 400 yards to the north. Sigsbee would state later that friends had told him Buoy No. 4 was a little-used one and none could recall a man-o’-war ever using it.

Nevertheless, Buoy No. 4 is where the Maine came to rest. The ship secured, Sigsbee undertook the protocol-required visits to the appropriate Spanish civil and naval authorities. He saw neither nervousness nor signs of concern on their parts. For almost a month the Maine lay tied up. Captain Sigsbee and his officers had infrequent contact with Spanish officials and the populace, and the crew was not given shore leave. Recollections of the tenor of the Spanish ashore were that it was of reserved politeness.

Only two isolated instances gave any indication of impending trouble. In the first, an unknown person had shoved an inflammatory anti-American Spanish-language circular into Sigsbee’s hand during a shore visit. The second was simply a few derisive calls from a ferryboat full of Spanish military and Cuban civilians returning from a bullfight in nearby Regla. These events were taken as isolated instances and of no great concern.

Yet despite the absence of widespread open hostility, the Maine’s skipper ordered that an unusually sharp lookout be maintained at night. Instead of the normal reduced in-port watch, Sigsbee required a quarter-watch for night hours so that one quarter of the crew was instantly available to man the Maine’s secondary batteries—with 6-inch ammunition beside the guns. Although visitors were allowed aboard, very few came, and those who did were carefully watched and followed discreetly lest any package be left behind. But so quiet was the situation that Sigsbee wrote the Secretary of the Navy in early February that he was confident of the ship’s safety.

At 9:10 pm, February 15, the Maine’s bugler sounded Taps, its mournful, long notes echoing across the placid but foul-smelling harbor waters. The day had been another quiet, uneventful one. As darkness settled, the watch was strengthened per Sigsbee’s orders. The lights of Havana flickered along the shoreline as the crew, unquestionably bored with their long confinement aboard ship, turned into their bunks.

Thirty minutes later Sigsbee had just completed a letter to his family and was placing it in an envelope when he was suddenly “jarred by a bursting rending, crashing roar of immense volume.” He rushed from his cabin. Fire, smoke, intense structural damage—particularly in the forward part of the ship—greeted his eyes. The ship was slowly settling by the bow into the mud of the harbor. It was immediately obvious to all on board and those ashore that some sort of huge explosion had torn the ship apart. But Sigsbee’s well-trained crew did not panic, though some crewmen trapped by fire or wreckage began to dive overboard. Then cries for help began to pierce the night. Sigsbee quickly saw conditions out of human control. There was no power, fires were spreading, and there was obvious danger of more explosions. Thus he gave the command to abandon ship.

Help came rapidly from several directions. Crewmen were able to launch several of the Maine’s boats, which began rescuing men in the water. Then a boat from the nearby steamer City of Washington arrived as well as several manned by Spaniards. All joined in rescuing wounded and swimming men from the water. But smoke, flames, and sporadic small explosions continued throughout the night.

With dawn all that remained visible of the Maine was a mass of twisted and charred metal poking above the dark harbor water. Only the rear or mainmast, with its circular crow’s nest still intact, remained erect to indicate that the pile of bent metal had been a ship. That mast now stands in Arlington National Cemetery as a memorial to those who lost their lives; today, beneath the Arlington mast rest the remains of 229 crewmen, 167 of whom are marked as “Unknown.” More than 250 officers and men were lost. The later-recovered foremast stands today at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md.

Just over an hour after his ship had literally blown up under him, Sigsbee telegraphed the Secretary of the Navy telling him of the disaster, crew losses as he knew them, and the fact that Spanish authorities had already expressed what he believed to be genuine concern and sorrow. He carefully included the statement that “public opinion should be suspended until further report.” Unfortunately, regulation of public opinion was not within the capability of the Secretary of the Navy.

In the hours immediately following, Sigsbee maintained a public silence, but in another telegram to the secretary he asked that divers be sent immediately to recover the ship’s code book, as well as any evidence that might bear on the cause. He then ventured: “The Maine was probably destroyed by a mine. It may have been done by accident. I surmise that her berth was planted previous to her arrival; perhaps long ago. I can only surmise this.”

Six days later a U.S. Navy court of inquiry went into session aboard the U.S. lighthouse tender Mangrove in Havana harbor. From the record there does not appear to have been any preconceived ideas as to the cause of the explosion. The court’s investigators looked at what they believed was every conceivable possible cause. Evidence was taken from survivors and witnesses, and observations by Navy and contract divers. The court concluded that the explosion had been forward of her bridge and a little to the port side, an area that included coal bunkers and full powder magazines.

Because the Maine was a coal-burning ship, the court sought evidence of undetected fire in one or more of the coal bunkers. Testimony stated that most of the bunkers near the site of the explosion, as well as those that still contained coal, had been checked within 24 hours of the explosion. Most of the bunkers near the site of the explosion had been empty. Bunker A-16 on the port side had been full, filled in November 1897 at Norfolk, Va., with 40 tons of coal and untouched since.

In front of A-16 were two empty bunkers. A-16, the crew testified, was not normally readily accessible; also, it was usually the first to be filled and the last to be emptied. Access to A-16 was through the other two or by an emergency hatch. The two empty ones had been painted the day before and their doors were then kept shut. Coal had been taken from the starboard-side bunkers. The court carefully questioned the engineering personnel about inspection of the bunkers, especially A-16. Inspections had been carried out on schedule and nothing untoward detected. The last inspection had been at 7:45 on the night of the explosion.

The court turned to the boilers. It was discovered that only two were in use—the two aft ones, and these with but 100 pounds of pressure rather than the at-sea loading of 120. No evidence of cause was found here. What about paint? Testimony revealed that all paint was in the aft section of the ship, where no explosion had occurred. Even medical supplies of an inflammable type had been stored aft.

The magazines where Maine’s full store of powder and projectiles were stored came under scrutiny. Again, no evidence of cause was found. Sigsbee had been strict about crewmen wearing slippers on entering the magazines and access was rigidly controlled. Temperature checks were diligently carried out and all systems were in working order. Further, divers discovered that the entire contents of the forward magazines had not exploded nor had the projectiles detonated.

At this point the court turned its focus to possible outward causes. Evidence emerged that seemed to indicate that possibly here lay the cause. A diving team testified that part of the keel was at one point found to be within 18 inches of the surface and bent upward in the form of an inverted V. One of the team contended that he believed some of the plates on the port side had been bent inward, though some were bent outward. But the divers confessed they could see but 12 to 18 inches at any one time—their electric lamps proving no better in the murky harbor waters.

Two pieces of evidence that hinted at sabotage were presented but were given little credibility by the court. The first was testimony of an anonymous Spanish-speaking civilian who contended he had heard three Spanish military men talking with a civilian about blowing up the Maine. The second was an anonymous letter received by the American consul after the fact that told of a plot by several Cubans to blow up the ship for monetary reward. But it was later found that these were fictitious and without credibility. Further, the court found no evidence of neglect or culpability by the ship’s officers and crew.

The court took testimony for 18 days, deliberated for four more, then, on the 23rd day—Monday, March 2l, at 10 am—announced its verdict: The Maine had been destroyed by a mine, the detonation of which caused a partial explosion of two or more forward magazines—a conclusion reached in part by testimony of several witnesses who claimed they heard two distinct and separate explosions.

But meeting concurrently with the American court was a Spanish one, and its findings disagreed with those of the American court—they contended the cause was internal. They, too, had evidence from divers. One Spanish diver stated the starboard forward side of the vessel was bulged outward and that the bilge and keel “throughout its entire length extant, were buried in the mud, but did not appear to have suffered any damage.” Another testified that “the entire vessel forward appears open, having undoubtedly burst toward the outside.”

Other witnesses pointed out the lack of any waterspout one could have assumed to have been present if a mine had detonated. Also, there was a sharp crack to the explosion rather than a muffled report of an underwater type. And, there was no evidence of dead or stunned fish from an underwater explosion. The Spanish divers also reported the lack of any electrical wires that could have been used to send an impulse to a submerged mine.

But what today seems to be equally important is that two factors were not discussed by either court. First was lack of reason for a mine to have been present at that buoy. This anchoring station was within the confines of an enclosed harbor, with shipping always close about, not a logical place to set a mine for defensive purposes. A more logical site would have been outside or at the entrance to the harbor. Indeed, it later emerged that the Spaniards had not mined the other major port—Santiago—until after war had been declared by the United States. The second factor was the lack of any discussion of gas.

While the Spanish court’s findings seemed to factually challenge those of the United States, they were peremptorily rejected by the American public. The Hearst press screamed for war, and war it would be—what became known as that “splendid little war.” The loss of the Maine did not cause the Spanish-American war but it was certainly a catalyst and it provided a catchy battle cry—“Remember the Maine” much as did “Remember Pearl Harbor” 43 years later.

In any event, the war ended and 12 years passed. The United States became the owner of large overseas colonies and an international power. In its exuberant youthful strength it forgot much of its antagonism toward Spain that the memory of the Maine had once engendered. But then a growing number of requests and petitions began to reach official Washington to have the Maine raised and the bodies of lost men recovered. Further, it was found that her tangled remains had become a hindrance to shipping. Then there was always the lingering question as to whether raising the ship would reveal any new evidence to confirm or refute the mine theory.

So in 1910 Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to raise the Maine. A large cofferdam was erected about the remains and pumps went to work. With the emergence of the battered, slime-covered hulk in November 1911, the Navy convened a second court. But the findings of this one were about the same as those of the original: The Maine had been destroyed by an exterior explosion. A minor difference was that the second court believed the site of the explosion was more aft, and this had been of a low order but had detonated the 6-inch reserve ammunition. That seemed to settle the matter for all time, though the source of the initial explosion was never found nor determined with certainty.

The question of intent also remained. If the explosion was accidental, a latent mine was possible. So, too, was an internal accidental cause. But the courts found no evidence of such. If the explosion was deliberate, was it sabotage, and if so, by whom? An explosion of that magnitude would certainly have required prior planning and its execution certainly more than one individual. The Maine’s watch had never spotted any person swimming toward the ship pushing a bundle ahead, nor had a small boat approached her in the manner of the recent attack on the USS Cole.

A submersible vessel of the type of the CSS Hunley was within the realm of possibility, but the existence of such a craft would surely have been known to the U.S. authorities and thus would have led to precluding the Maine’s visit to Havana harbor. As for a member or members of the crew being guilty, there was never the slightest evidence of dissatisfaction or disloyalty. It also seems a bit odd that over the years, even up to the present time, if there had been persons responsible, either as individuals or acting on the part of a foreign government, that this would not have emerged.

Significantly missing from review by both courts was the subject of gas. According to experts in the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Mines, in 1898 knowledge of coal gases was very scant. Today it is known that coal gives off the very deadly and highly inflammable methane gas, an odorless and tasteless gas which, when present in the air in a ratio of but 5 to 14 percent, is extremely dangerous. But in 1898 this was not common knowledge.

At that time, ships often lay at anchor with the below-decks temperature running over 100 degrees, with crude electrical systems by modern safety standards, no forced air ventilation, and no devices present to detect the presence of dangerous gas. Moreover, the Maine’s crude (again, by modern standards) electrical power-generating system was located adjacent to Bunker A-16. Such were the conditions aboard the Maine—a spark, fire, and explosive condition if ever there was one.

Oddly, while the American courts failed to address any gas theory, the Spanish one did. In its summation, that court noted the proximity of ammunition storage to the coal bunkers, a fact it said should have required “ventilation sufficient to prevent the accumulation of gases and the development of caloric….” The Spanish court leaned heavily toward spontaneous combustion of coal as the base cause, which then ignited the ammunition. The Spaniards apparently had come close. With the benefit of hindsight and modern technology, today it seems most likely that methane gas was the culprit for the loss of the Maine.

In reviewing all the factors available today it seems quite certain the explosion was internal and accidental. There was no evidence of disloyal action by any U.S. crewman. Evidence of sabotage would certainly have surfaced by now, the more so with the several changes in governments of the countries involved. There was no valid reason for a mine to have been placed in such a harbor location. But all the conditions for a methane explosion were present in quantity. There was the full-for-some-time and untouched Bunker A-16. It was located in close proximity to an active electrical-generating plant where sparks can be a way of life, particularly in that era of crude electrical technology. In the language of a popular cliché, it was an accident waiting to happen.

This writer became interested in the fate of the Maine in the late 1960s and had begun research in the National Archives. With the benefit of limited technical training, I began to seriously question the external theory. Taking the evidence I had accumulated, I visited the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Mines. Discussions with several of their senior engineers brought forth the belief on their part that methane gas had been the probable culprit. I wrote a rather lengthy article on this and sent it in 1971 to the U.S. Naval Institute for possible publication in their Proceedings magazine. A greatly reduced version of the article was subsequently published in their February 1972 issue.

That article was followed in 1976 by Admiral Hyman Rickover’s book on the explosion of the Maine. His consultants leaned toward the spontaneous combustion of gas theory. They concluded that external cause did not seem to fit the evidence. But there are still those who question the spontaneous explosion theory, contending that such combustion would have been detected. The more one reads, the more methane gas seems to appear as the guilty culprit.

It was with fitting ceremony, on March 16, 1912, that the remains of the USS Maine, with the Stars and Stripes, were towed out to sea and allowed to settle to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. n

The author, being of Army service, has little knowledge of Navy ceremonial protocol, and is unaware of any surrounding the resting site of the Maine. But it would seem an appropriate gesture, if one does not already exist, for every U.S. war vessel passing close by to have a ship’s party on deck and the colors dipped in salute of the Maine’s fallen men.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments