By Allyn Vannoy

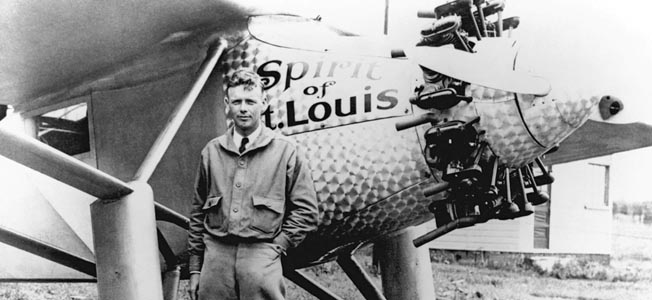

Joseph J. Foss (April 17, 1915–January 1, 2003) was born on a farm near Sioux Falls, South Dakota. When Foss was 12, he saw Charles Lindbergh while the “Lone Eagle” was touring with his Spirit of St. Louis airplane.

Foss’s Flying Circus on Guadalcanal

In 1933, upon the death of his father, Foss took over the running of the family farm, but the crops and stock were destroyed by dust storms. He then worked at a service station to pay for books and college tuition at the University of South Dakota––and for flying lessons. By 1940, after earning a pilot certificate and a degree in business administration, he enlisted in the Marine Reserves to join the Naval Aviation Cadet program.

After being designated a Naval Aviator and commissioned a second lieutenant, Foss served as an instructor and later attended the Navy School of Photography, at which time he was assigned to Marine Photographic Squadron 1 (VMO-1). Eager to see combat, he qualified in Grumman F4F Wildcats while still assigned to VMO-1 and was eventually transferred to Marine Fighter Squadron 121 (VMF-121) as the executive officer.

In October 1942, the squadron was deployed to the South Pacific and became part of the Cactus Air Force on Guadalcanal (“Cactus” was the code name of the island). On combat missions, he led a flight of eight Wildcats that became known as Foss’s Flying Circus. He shot down his first Japanese plane, a Zero, on his first combat on October 13, but was nearly killed himself.

By the time Foss left Guadalcanal in January 1943, his Flying Circus had shot down 72 Japanese aircraft, Foss being credited with 26. For his actions he received the Medal of Honor from President Roosevelt in a White House ceremony and appeared on the June 7, 1943, cover of Life magazine.

He eventually became a general in the Air National Guard after the war, the first president of the American Football League, president of the National Rifle Association, and governor of his home state of South Dakota.

The Mixed Legacy of Charles Lindbergh

Charles Lindbergh went from hero to villain to hero again. Born in 1902 near Little Falls, Minnesota, he was an unknown airmail pilot until his historic solo flight from New York to Paris in 1927. Suddenly he was thrust into the national spotlight and regarded as one of America’s great aviation heroes, drawing huge crowds wherever he went.

In the 1930s, however, Lindbergh, impressed with Nazi Germany’s advanced aircraft program, praised the Third Reich while criticizing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s foreign policies. Lindbergh became a leading spokesman for the antiwar America First Committee––a group opposed to the United States’ becoming involved in European politics and a possible new war. Germany even awarded Lindbergh a special medal (which he later returned). Advocating that the United States sign a neutrality agreement with Germany, he resigned his commission in the Army Air Corps in April 1941 after Roosevelt publicly denounced him. Lindbergh was widely vilified by the American public as being a Nazi sympathizer and an anti-Semite. Some even accused him of being a traitor.

Once Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Lindbergh changed course and supported America’s entry into the war. He tried to reenlist, but his request was refused. In April 1944, Lindbergh went to the Pacific as a civilian adviser to the U.S. Army and Navy and flew approximately 50 combat missions against the Japanese. After the war he maintained a low profile until his death from cancer in 1974.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments