By Don Troiani

The American Civil War may well have been the first major conflict in which soldiers felt the need to wear some sort of a personal identification badge in the event that they were killed or wounded in battle. A great apprehension among soldiers was “the nameless grave,” the fear that loved ones might not recover their remains or learn what had become of them. Although hand-written slips of paper with soldiers’ names and information were often attached to their uniforms before they went into battle, a more reliable solution quickly took hold—the personal identification badge.

In the days when military secrets were not so secret, such badges openly proclaimed not only the soldier’s rank, but also his regiment and often his corps and division. These badges fell into three categories: identification disks with die-stamped information, identification badges with engraved inscriptions, and corps badges that displayed the same information but within the shape of one of the various army corps symbols.

In the days when military secrets were not so secret, such badges openly proclaimed not only the soldier’s rank, but also his regiment and often his corps and division. These badges fell into three categories: identification disks with die-stamped information, identification badges with engraved inscriptions, and corps badges that displayed the same information but within the shape of one of the various army corps symbols.

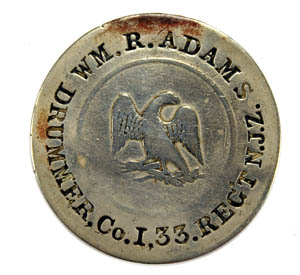

Identification Disks: Precursor to the Dog Tag

The first type was a coin-like disk, often stamped with the soldier’s hometown and state, that would aid in identifying his body for burial or shipment home. Some consider this type of badge to be the forerunner of the World War II-era “dog tags.” Fabricated of gilt brass or white metal, they were typically worn on the chest suspended from a patriotic clasp featuring an eagle or a favorite commander such as George B. McClellan or Philip Kearny. Generally, there was an eagle or hero on one side of the disk, often with the inscription “War of 1861,” since no one knew how long the conflict would last. On the reverse side, the soldier’s name, company, regiment, and hometown were stamped with individual letter punches. Occasionally, instead of a patriotic figure on the face of some disks, a blank space was provided for listing the battles in which the soldier had participated. Soldiers and jewelers often used U.S. quarter-dollar silver coins as an inexpensive substitute for commercially produced disks. One side of the coin was shaved smooth to accommodate the engraved information. A hinged T-bar pin was sweat-soldered to the reverse, leaving the coin motif fully visible, possibly as proof of the silver content.

Cloth Badges

Early in the war, Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny ordered his troops to wear a red cloth patch on their caps so that he might recognize the soldiers of his command. These were quickly accepted as a proud symbol by the men of his hard-fighting division. In March 1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, devised a similar system of cloth badges to be worn on the caps of the men in each army corps so that troops from different commands could be easily distinguished by their officers. The cut-out cloth emblems took various shapes: a circle for I Corps, a three-leaf clover for II, a diamond for the III, and a Maltese cross for V. Each badge’s shape was also a different color to differentiate the three divisions composing each corps: red for the 1st Division, white for the 2nd, and blue for the 3rd. The concept was immensely popular with the soldiers, who quickly began to have their own customized badges fabricated and engraved by jewelers and pin makers. Not to be outdone, sailors in the Navy also adopted pin-on badges, some adorned with ship profiles such as ironclad monitors.

Both Humble and Ornate

Northern jewelers nationwide were astonishingly quick to exploit the ready market of soldiers eager to possess such a badge and, indeed, to have a better one than their comrades. Newspaper ads for badges were plentiful, and soldiers were enlisted as “agents in the field” for various firms. Many badges were simple thin-sheet silver stampings or cut-outs, with an engraved inscription, or colored enamel-filled center, or both. Some, however, were ornate gold and silver wonders of craftsmanship produced by the most prestigious American firms, such as the farewell badge that famed Brig. Gen. Joshua L. Chamberlain pinned to the chest of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin in May 1865. Made by Tiffany & Company, which was a premier supplier of military goods of every type imaginable, from uniform buttons to weaponry, the badge was made of enameled gold displaying the Maltese cross of V Corps on a white ground. Edged with diamonds, the badge was crowned with a larger center diamond that was reputed to have cost $1,000—an astounding sum at the time. After the war, Chamberlain commissioned Tiffany to make a gold and enameled charm bracelet for his wife, Fanny, which incorporated military and rank symbols as the primary ornaments.

Northern jewelers nationwide were astonishingly quick to exploit the ready market of soldiers eager to possess such a badge and, indeed, to have a better one than their comrades. Newspaper ads for badges were plentiful, and soldiers were enlisted as “agents in the field” for various firms. Many badges were simple thin-sheet silver stampings or cut-outs, with an engraved inscription, or colored enamel-filled center, or both. Some, however, were ornate gold and silver wonders of craftsmanship produced by the most prestigious American firms, such as the farewell badge that famed Brig. Gen. Joshua L. Chamberlain pinned to the chest of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin in May 1865. Made by Tiffany & Company, which was a premier supplier of military goods of every type imaginable, from uniform buttons to weaponry, the badge was made of enameled gold displaying the Maltese cross of V Corps on a white ground. Edged with diamonds, the badge was crowned with a larger center diamond that was reputed to have cost $1,000—an astounding sum at the time. After the war, Chamberlain commissioned Tiffany to make a gold and enameled charm bracelet for his wife, Fanny, which incorporated military and rank symbols as the primary ornaments.

Confederate soldiers also used identification badges, but not nearly to the extent of their Yankee foes. Most were made of thin-sheet silver or brass and incorporated designs such as stars and crescents. Surviving examples of these badges are exceedingly rare, and fakes abound.

Quite a few Union identity disks have survived to the present, a large number having been found by relic hunters on Civil War battlefields and camps. Many museums do possess some badges, but few have more than two or three on display at any given time. You can see many more at a good Civil War collector show in the dealers’ cases or when a collector decides to mount a display of badges.

I found it interesting when you talked about the changes that civil war identification badges suffered. In my opinion, it’s interesting to know about how back in the day, different types of insignias were worn to help identify soldiers. Plus, it’s great that through different museums and collectors, we’re able to look back in history and see how the personal identification badge was born. I think you did a great job explaining the importance of personal batches for military enforcement.