By Blaine Taylor

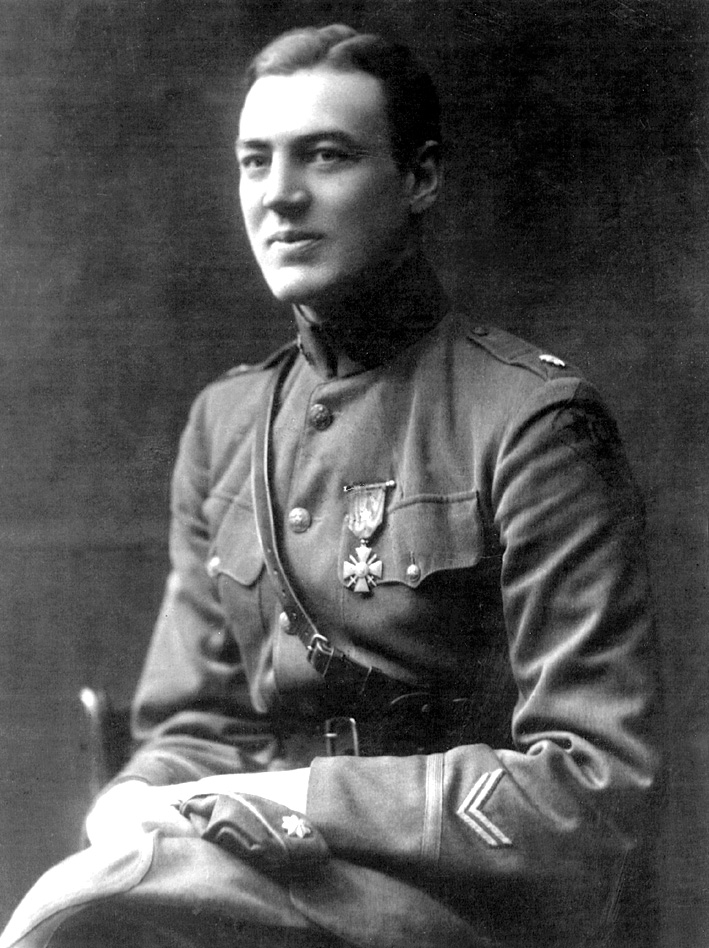

In July 1918, 30-year-old U.S. Army Captain Hamilton Fish, Jr., was in war-torn France with the 15th New York National Guard Regiment—also known as the (U.S.) 369th Infantry. This would not have been unusual, except that the regiment was an all-black unit led by white officers. Furthermore, the regiment was under French command because it was not allowed to fight with the then rigidly segregated American Army proper. Nevertheless, blood was red no matter what the skin color, and battle was about to be waged.

As Fish noted in his 1991 autobiography, Hamilton Fish: Memoir of an American Patriot: “The Germans launched an all-out offensive—the Battle of Champagne-Marne—against our lines. Just before the battle began, I wrote what I thought would be my last letter to my father:

“‘Dear Father: … I am assigned with my company to two French companies to defend an important position [a hill] against the expected German offensive.

“‘My company will be in the first position to resist the tremendous concentration against us and I do not believe there is any chance of any of us surviving the first push. I am proud to be trusted with such a post of honor and have the greatest confidence in my own men to do their duty to the end. The rest of our Regiment is dug in far to the rear except for L and M companies; the latter is holding a village in our rear.

“In Case I Am Killed…”

“‘My company is expected to protect the right flank of the position and to counterattack at the sight of the first Boche [as the French called the Germans]. In war some units have to be sacrificed for the safety of the rest and this part has fallen to us and will be executed gladly as our contribution to final victory. How fond I am of you, and to thank you for all your care and devotion—words utterly fail me. I want you in case I am killed to be brave and remember that one could not wish a better way to die than for a righteous cause and one’s country. Your affectionate son, Hamilton.’”

He was not killed, however. “When the attack did come, my company was ready, holding its position despite the ferocity of the fighting. Company K—my company—lost three dead, and had six wounded and four poison gas casualties. I survived unscathed, though my horse was killed during an artillery attack, my helmet was hit by shrapnel, and I had a few other close scrapes.”

The German offensive had failed, leading to what their Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff was to call “the black day of the German Army,” August 8, 1918. The French commander of Fish’s regiment, General Gouraud, noted that “It was a hard blow for the enemy. It is a beautiful day for France.”

Added Fish, “We began to sense that the tide of victory was turning in our directions.”

Actually, Hamilton Fish, Jr., had almost not become a soldier. He came from a dyed-in-the-wool Republican political family and hailed from the same district as his later “friend” and bitter foe, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His great grandfather, Nicholas Fish, was a colonel in the Revolutionary War, the first Adjutant General of the State of New York, the first Supervisor of Revenue in New York, and, as he told it, “An intimate friend of Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton.”

His grandfather, also named Hamilton Fish, was a member of the House of Representatives, Lieutenant Governor and Governor of New York, one of its two U.S. Senators, and U.S. Secretary of State under President Ulysses S. Grant. Our Hamilton Fish was born in Garrison, NY on December 7, 1888, while his father—also named Hamilton Fish—was Speaker of the New York Assembly at the state capital of Albany as well as a member of Congress.

Our “Ham” Fish attended St. Mark’s School and graduated from Harvard University (as did FDR) at the age of 20 with a cum laude degree in political science. He was offered an appointment to teach government and history at Harvard, “which I regretfully declined,” he noted.

As he added later, he was proud of his pre-World War I heritage and record, and had every right to be: “I am directly descended from Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam, and Louis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Robert Livingston, the first Lord of the Manor, and of Thomas Hooker.” (His later nemesis, FDR, was also of Dutch descent.)

From Harvard to War

“Was Captain of the Harvard football team and am the only remaining [in 1979] member alive of Walter Camp’s All-Time All-American Football Team. Was three times elected on the Progressive Ticket [Theodore Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party], and a member of the [State] Assembly from Putnam County.” (FDR had also served in the State Legislature.)

After graduation from Harvard in 1910 as an All-American tackle (and later being named to the College Football Hall of Fame), young Fish earned two law degrees before going on to the State Assembly. Then came the war.

“I had served for two years in the National Guard,” he remembered later, “training at Plattsburg, N.Y., while I was an Assemblyman in the New York State legislature. My commanding officers were impressed by my performance and recommended that I be promoted to captain. An examination was required to achieve the promotion, but I had studied the drill regulations extensively and knew I could pass the exam.…

“On the day of the examination, I was met by a major I did not know who himself had not been made captain until he was well over 50 years old. He asked me a number of questions that had nothing to do with military training and declared me too young for a captaincy. I did not know then that my great grandfather Nicholas Fish had been the youngest major ever commissioned in the Army, aged 18 years and three months. If I had known, I would have invoked his example. As it was, I merely told the major that I thought my age, experience and background were sufficient to make me a qualified candidate.

“But the major would not even allow me to take the exam, and told me that if I did take it, he would ask me questions about cooking that I would be sure to fail. I protested that whatever my knowledge of cooking, I knew the drill instructions as well as he did, but the major persisted in his refusal.”

In New York City, a disappointed Fish ran into Colonel William Hayward of the National Guard, who was then organizing an all-black regiment to train for combat duty in France. “He asked me if I wanted to join the Regiment as a captain. I accepted his offer on the spot and became one of the first officers of what was later designated the 369th Infantry Regiment, the famed Harlem Hell Fighters.”

War was declared on Imperial Germany on April 2, 1917, and the following summer two thousand regimental men began their training at Camp Whitman, NY. In October they received orders to travel to Spartanburg, SC for more combat training.

Dealing With Racial Tensions

Fish sensed trouble. He wrote: “Realizing that the presence of so many black troops in the predominantly white and segregated town … could cause trouble, I telegrammed Franklin Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, telling him of my fears and requesting that he do what he could to have us sent directly to France.… Despite my appeal to Roosevelt, our orders remained unchanged, and we went to Spartanburg for 12 tension-filled days. It was made obvious that we were not welcome in the town. Soldiers were assaulted, forced off the sidewalk and subjected to other racial harassments.”

Calling a hasty conference with local officials, a forceful Captain Fish informed them “that if any of the town’s citizens sought by force to interfere with the rights of the black troops under my command, I would demand that swift legal action be taken against the perpetrators. This quieted things down temporarily.” On October 24, the regiment was recalled to Camp Whitman.

There, however, the 369th faced more trouble when it found itself housed next to a white Alabama regiment. “Early one afternoon, I learned that the Alabamians intended to attack us during the night … I had to borrow ammunition … as we had none. After arming our soldiers, I and my fellow officers told them that if they were attacked, they were to fight back; if they were fired on, they were to fire back.”

A midnight meeting between Fish and a trio of Alabama officers led to a later newspaper story that he had challenged them to a fistfight (which he denied), but in reality, all three returned to their regiments to prevent what he asserted “would be a massacre … and I was left standing there with my revolver cocked in the firing position, unsure how to release the hammer without discharging a round,” as he recalled in 1991.

On the way overseas to France, Fish discovered to his dismay that their troop convoys were steaming without benefit of destroyer escorts at a time when German U-boats were sinking all manner of Allied vessels. Again, he wrote to FDR: “I am writing the following facts to you as a friend who has confidence in your discreetness and as a friend who believes in your good judgment and ability to remedy a condition which in the near future will endanger the lives of thousands of American soldiers … I have no desire to criticize anyone and only hope to remedy the condition before it results in a disaster.”

They landed in Brest, France, on December 26, 1917. After being transported in icy-cold, unheated rail cars to the port of St. Nazaire, Fish and his men found themselves, he wrote in his memoirs, unexpectedly employed as stevedores, “making preparations for other American troops on their way to France.” He continued, “We had been trained to fight as soldiers, not to work as laborers, and all of us were anxious to get to the front lines, but the American military command was reluctant to integrate the armed forces by assigning black troops to white regiments. (As a Congressman during World War II, I played an active role in trying to integrate the armed forces.)”

Integration reform did not take place in any of Northern-born President Roosevelt’s four administrations, but in that of his Southern-born successor, Harry S Truman of Missouri, who, like Fish, was a World War I veteran.

Canteens Full of French Wine

Placed under French command by American Expeditionary Force Commander General John J. Pershing (who had commanded black cavalry troops against the Apaches in the earlier days of his career), the 369th turned in its American gear at Chalons, and was temporarily issued “French rifles, helmets, belts and canteens that had no water but, much to the delight of the men, were filled with French wine. After a month or so, we were judged ready to fight … and assigned to the French 4th Army under the command of the famous one-armed French Gen. Gouraud, with whom I became quite friendly, thanks to my fluency in French.”

On the way to the front, they were suddenly hit by a German artillery barrage: “It sounded like a gale at sea. Several shells exploded on the battery wounding a number of French soldiers and some of mine as well.… We filed into our new positions in the trenches, which had rows of barbed wire extended in front. When we weren’t standing in the trenches, we slept in our dugouts, which were 50 feet deep.”

During one nocturnal incident, a French soldier upset a box of grenades that then tumbled down into the sleeping quarters, wounding a trio of Fish’s men. “I went down into the dugout accompanied by a French lieutenant to see what I could do. The lieutenant was overcome by the sight and fainted. As a result, I had to carry all three wounded soldiers 50 feet to the surface. Amazingly, despite the seriousness of their head and body wounds, all three survived.”

In September 1918—while Fish was attending staff school at Langres—Germany launched its final offensive of the war in the Meuse-Argonne. According to National Guard records, “at Sechault, France on Sept. 29, 1918, from Harlem streets and other New York City neighborhoods they came … marched toward a date with destiny in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive …. ‘The day dawned clear and cool. There was expectancy in the air.’ A fierce artillery barrage preceded the attack by the 369th, nicknamed the ‘Hell Fighters’ by the enemy.

“A Horrifying Exchange of Machinegun and Artillery Fire”

“After a brutal struggle during which heavy casualties were sustained, Sechault was taken and the 369th dug in to consolidate their advance position. The action depicted earned the (French) Croix de Guerre for the entire Regiment, but the Meuse-Argonne claimed nearly one-third of these black fighting men as casualties. This distinguished National Guard Regiment left its proud mark on the AEF as “The Regiment that never lost a man captured, a trench or a foot of ground.”

As for Fish, he recalled, “I rushed back to my company, just in time for the fighting, which raged incessantly for the next 48 hours in a horrifying exchange of machinegun and artillery fire. When it was all over, 30% of my Regiment had suffered casualties. For my part in the battle, I was awarded the Silver Star. The citation read:

“‘… Constantly exposed to enemy machinegun and artillery fire, his undaunted courage and utter disregard for his own safety inspired the men of the regiment, encouraging them to determined attacks upon strong enemy forces. Under heavy enemy fire, he assisted in rescuing many wounded men and also directed and assisted in the laborious task of carrying rations over shell-swept areas to the exhausted troops.’”

In his 1991 memoirs, Congressman Fish added, “The Meuse-Argonne battle was the single most important battle of World War I. Had the Germans succeeded, they would have had an open path into Paris and to the North Sea, but we stopped them. It was now only a matter of time before Germany was compelled to surrender,” which it did, by requesting an Armistice on November 11, 1918.

Fish wrote to his father, “It seems almost a dream, in spite of the fact that peace has been discounted for the past two weeks. I am glad the killing of human beings is over and hope that it will be a lost art in the future.”

Thus, a frontline soldier who had seen war firsthand would become the Congressman of 1920-1944 who opposed FDR on the thorny issue of America’s entry into World War II—until Pearl Harbor.

Fish’s Journey Home

Nevertheless, he wrote, “The record that we, the men of the 369th, compiled on the field of battle was an outstanding one. We spent 191 days in the frontline trenches, longer than any other American regiment. We were the first Allied regiment to reach the Rhine.… I will always remember the brave black men who served with me in the trenches of France.… Nor will I forget the bravery of my loyal sergeants.… At the end of World War I, I told my men, ‘You have fought and died for freedom and democracy. Now, you should go back home to the United States and continue to fight for your own freedom and democracy.’”

Back home, Hamilton Fish was one of three who wrote the Preamble of the American Legion. The Legion made him its only living honorary National Commander.

In 1920, when FDR ran for vice president as a Democrat and was defeated, Hamilton Fish was elected as a Republican Congressman from the Orange-Dutchess-Putnam District, which included his rival’s home, Hyde Park. He served in Congress for 25 years and was the ranking minority member of the Foreign Affairs and Rules Committee, despite FDR’s intensive but failed attempt to see to his defeat for re-election in 1942.

Fish introduced the bill in Congress to bring back the body of the first Unknown American Soldier, who today rests at Arlington National Cemetery, and was selected to place the wreath on the Tomb at the burial services on November 11, 1921.

In 1922, he introduced and secured passage of the Palestine Resolution—the American version of the British Balfour Resolution—for a Jewish homeland in Arab-occupied Palestine. He became the chairman of the first Congressional Committee in 1930-1931 to investigate Communist propaganda and activities in the United States. At the Oslo Conference on August 15, 1939, Fish headed an American delegation to the Interparliamentary Union two weeks before Hitler invaded Poland, and introduced the plea for a 30-day moratorium seeking to settle the critical Danzig war issue by arbitration.

All of this earned him the enmity of President Roosevelt, who refused to allow him into the White House, even after December 7, 1941, allegedly for an untrue remark he had once made about FDR’s mother. For his part, Congressman Fish was against both the Lend-Lease and Selective Service acts as being too warlike, and once even suggested that his by now hated rival should invite Communist Russian Marshal Josef Stalin to the White House.

Fish’s Legacy

According to biographer James MacGregor Burns in Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom, 1940-45, “[FDR] reserved his hatred for people in his own social world, such as Hamilton Fish, who he felt had betrayed him; as they did for him.” In the campaign of 1940 came the famous “Martin, Barton and Fish” speech and radio address by FDR in which the President singled out the trio of top Republican conservatives as his opponents.

FDR died in 1945 at age 62 and Fish, who died on January 20, 1991 at 102, lived long enough to see his rival’s Pearl Harbor activities called into question. He noted in an interview, “I have been studying Communism for 50 years. The Soviets themselves have turned against Roosevelt’s great friend Stalin.” As for the “Martin, Barton and Fish” epithet, he merely smiled, adding, “It got enormous applause. He had enormous popularity.”

Fish wrote five books, including FDR: The Other Side of the Coin—How We Were Tricked into World War II, and was lauded by American Legion Magazine for sponsoring successful legislation promoting veterans’ hiring and medical benefits. Fish also lived long enough to see the entire U.S. Armed Forces fully integrated with both blacks and women.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments