By Peter Suciu

While lightly armed cavalry already seemed anachronistic by the time of the Napoleonic Wars, the success of the Polish lancers in that conflict convinced many nations to adopt a similar fighting force. Founded by Jan Henryk Dabrowski, the legion brought with it a form of square-topped shako that was already being used by Austrian lancers in Galicia. The Polish lancers, known as Ulans, fought not only with lances but also with sabers, pistols, and rifles. They wore a double-breasted jacket with a colored panel on the front, along with their distinguishing headgear. The square-topped shako evolved to resemble the traditional Polish cap and thus became known as a czapka, the Polish word for cap. The original cap dated back to the 17th century and was made of cloth and edged with fur.

By 1770, the lancer cap had evolved into the distinctive four-sided top cap that is most recognizable today. This evolved in the early 18th century into a cap that was supported with stiff ribbed sides with a peak added to the front. The Polish Legion was among Napoleon Bonaparte’s earliest foreign troops, and these men saw action in numerous campaigns, including those in the West Indies, Italy, Egypt, and Russia. Throughout the wars, the forces of the newly established Grand Duchy of Warsaw used the czapka not only for its cavalry units but also for infantry and artillery units, where the Polish headdress was used in place of the typical shakos that were popular throughout the rest of Europe.

The success of the Polish lancers inspired other nations to form their own legions. The standard 19th-century Polish cavalry version was a high, four-pointed cap with the regimental insignia on the front. Following the Congress of Vienna, the Duchy of Warsaw and other Polish lands were split up among Russia, Austria, and Prussia, with Russia gaining the lands and title of the Kingdom of Poland. Throughout the 19th century, both Russia and Austria fielded Polish units, with units on each side using the same tall czapkas.

Several versions of lancer caps were used throughout the 1830s and 1840s. The 1846 dress British Army regulations included the following description: “Cap-cloth; colour of the facings, eight inches and three quarters deep in front, nine inches and a half at back, and the top nine inches and a half square; gold cord across the top and down the angles; on left side a gold bullion rosette, with embroidered V.R., on blue velvet; round the waist a band, two inches wide, of gold lace, with a blue stripe; in front a gilt ray plate, with silver Queen’s arms and regimental badges; peak and fall of black patent leather, braided with gold; gilt chain, fastening to lion’s heads at the sides.”

This was the cap that was used by the lancer regiments in the famous Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War, but it was not the most commonly encountered version. This was the 1856 pattern of lancer cap and subsequent versions. As with the German models, over time the height of the British lancer cap was reduced, until it was just six and half inches high in the front and eight and a half inches at the top. From 1856 onward, feathers were generally worn on officers’ helmets, while other ranks wore a horsehair plume; the color of each was determined by the regiment. And while the British lancers took part in combat in many campaigns after the Crimean War, none of these were in Europe, and the lancers never again wore the cap into battle. In its place, the foreign service helmet (pith helmet) was used, and that was what Winston Churchill wore when he took part in the last British cavalry charge in the Sudan in 1898.

The French Army, following the downfall of Napoleon I, ceased to use the czapka, but the hat was brought back into service with the reformation of a new Imperial Guard under Napoleon III. The cap was vastly different in that it was far shorter than the earlier version, but as with most lancer caps it retained the characteristic four-sided top, which resembled a mortarboard of academic dress. This cap was used from 1857 until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. With the downfall of yet another Napoleon, the Imperial Guard was disbanded for good, and although the Garde Nationale à Cheval used a full-dress uniform that included the czapka, the cap was taken out of service for good following the end of the conflict in 1871.

Although most lancer units throughout Europe retained the basic look of the early Polish units, including the famous czapka, there were a few notable exceptions. One of these was in Portugal, a nation that traditionally followed British lines when it came to uniforms. In 1885, spiked helmets were issued widely throughout the Army, and some officers were outraged by this. One officer wrote, “If they take away our czapkas, they should also take away the lance, as one makes no sense without the other.” After a series of debates and disputes, the czapka was reintroduced in 1892 and modified in 1895. The new czapka retained the square top placed on the 1885 spiked helmet, but retained the rear peak, so that the result was not entirely a lancer cap but more of a lancer helmet, possibly the only such type of headdress in the world. These were used by Portuguese Lancer Regiments 1 and 2.

One other notable exception among lancer caps was used by the Paraguayan 4th Cavalry Regiment of Acà-Carayà, a unit that was first raised during the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870), which saw Paraguay face off against the forces of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. Although the war went badly for Paraguay, the Acà-Carayà reportedly fought well, and was called into action again in the Gran Chaco War (1932-1935) against Bolivia. The cap was made of leather dyed red, white, and blue for the colors of the flag, with an ornamental strip of local monkey fur attached to the top and a horsehair plume in the back. These caps remain in use today with synthetic materials—fortunately for the monkeys of the nation.

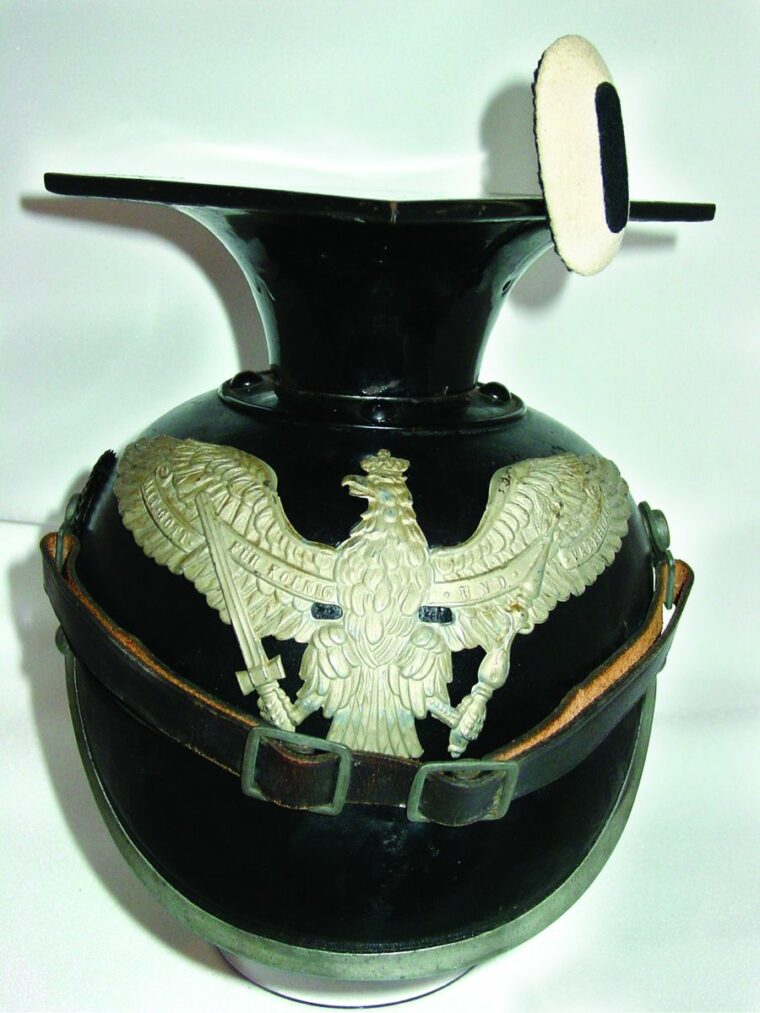

But it was the British and German versions that lived on and evolved into the most recognizable modern lancer caps. Prussian and German armies of the 19th century are widely remembered for their Pickelhauben (spiked helmets), a type of headgear that spread throughout Europe as well as North and South America. In fact, the Prussians had adopted that helmet from the Russians, who in turn had adopted the czapka from the Poles. The Prussians progressed from a Polish-style tall helmet, the Model 1843, to the shape more familiar to modern collectors of Imperial German headgear of the World War I era. Known as a Tschapka in German, this headgear consisted of a body of pressed blackened leather with a short visor on the front. On the left front was worn the national colors via a cockade, and after the unification of Germany a state cockade was worn on the right. These caps originally closely resembled the tall Polish version, but beginning with the Model 1867, a major reduction took place in the height of the cap, with the Wappen (front plate) now placed on the front of the shell.

The appearance of the lancer helmet, which was first modified in 1889 and then again in 1915 during World War I, closely resembled the mortarboard of academic dress. During the war, several ersatz models of the German Tschapka were used, including some made of tin and even felt, although collectors should know that the later varieties have been highly faked in recent years. At the outbreak of the conflict, the helmets used in the field were a gray color.

A new Polish legion was formed to fight alongside the French Army in World War I, and was known as the Blue Army. After the war, Poland was reestablished and the various units, regardless of which side they had served, retained the same basic traditions in the new Polish Army. By this time, the czapka was a headdress whose time had passed, but the Polish headgear lived on as it evolved from the tall leather czapka to the rogatywka (peaked cap). The asymmetrical, peaked, four-pointed cap was also based on the early square Polish caps that had been in use since the 14th century. While shorter and less rigid than the czapka, the cap retained the same basic shape.

The rogatywka was first used in the Polish-Soviet War during 1919-1920 and remained the ceremonial headdress of the Polish cavalry although the French-style Adrian helmet was used for combat. After World War II, the Polish Army adopted a more Soviet-style peaked cap, but in the 1980s the rogatywka reappeared as the primary headdress of the ceremonial honor guard at Belvedere Palace. Although it has been removed from widespread use, the modern Polish Army still uses the four-sided cap with certain orders of dress, retaining its ties to its historical past.

Following the success of the Polish Ulans, many nations adopted lancer regiments, complete with modified versions of the czapkas. By the outbreak of World War I, Germany, France, Austro-Hungary, Great Britain, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, and Russia all fielded lancer regiments, and most were still wearing the czapkas as dress caps. In the opening stages of the war, German, Belgian, and Austrian units wore the czapkas onto the battlefield. Special waterproof covers were used until the units were taken out of service as trench warfare made quick-moving cavalry a thing of the past.

While the Germans wore the caps onto the field during the Great War, their British rivals did not. By 1914, the lancer cap was reduced to use as part of the British Army’s dress uniform. As with the other continental versions, the British lancer cap had also transitioned from a tall cap to a shorter version, but there is actually conflicting evidence as to when the first lance cap pattern was introduced. Examples of these earliest czapkas, which date to just after the Napoleonic Wars, are rare indeed. Several patterns were used, but few examples of these helmets remain, even in museums.

At the outbreak of World War I, the British lancers were outfitted with peaked caps instead of their dress lance caps. After World War I, the lancer caps were generally retired by most nations in favor of more modern headgear, and even with dress uniforms the lancer cap was taken out of service in the British Army in 1939. Today, a few nations still carry on the tradition of lancers, which are now generally armored units, but the traditional lancer czapka saw its last charge 90 years ago.

Lancer caps were a unique form of headdress, but as with any item of militaria, they have been widely copied and faked. Because many of the parts are easy to remove and thus misplace, many examples are a mix-and-match of parts that don’t really belong together. Additionally, while many nations, notably the British, used these only in ceremonial roles, their examples are more plentiful than those of other nations, such as Germany, that wore them onto the field of battle.

Some later variations, notably the mid-war felt versions from Germany, have been so widely reproduced that collectors are wary of trusting any as being real. Other examples, such as those from the Polish Legion during the Napoleonic Wars, are so uncommon that few exist in private collections. Collectors are advised to look to reputable dealers when seeking out these items. Unlike the later steel helmets that eventually replaced them, the lancer helmet—with proper precautions—can make a lovely collectible from a bygone age.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments