By John Protasio

The concept of a ship that could submerge beneath the water and then resurface dates back as far as the late 1400s, when Italian Renaissance artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci claimed to have found a method for a ship to remain submerged for a protracted period of time. However, da Vinci refused to reveal his discovery to the world because he feared “the evil nature of men who practice assassination at the bottom of the sea.”

The Early Pioneers of Submersible Ships

A Dutchman, Cornelis Drebbel, built the first known practical submersible in 1620, using blueprints developed nearly 50 years earlier by English amateur inventor William Bourne, whose plans never got beyond the drawing board. A leather-covered, 12-oar rowboat, Drebbel’s craft was reinforced with iron against water pressure to a depth of 15 feet. He tested the submersible in the Thames while working under contract to the British court. King James I observed the tests, although it is probably apocryphal that the monarch ever made a test dive himself. Despite several successful tests between 1620 and 1624, the Royal Navy eventually lost interest in Drebbel’s invention, and none was commissioned or built.

During the latter years of the 17th century, a number of other European inventors and scientists worked on submarine designs. In 1680, Italian inventor Giovanni Borelli sketched plans for a submarine that could be sunk or raised using goatskins in the hull that were alternately filled or emptied of water by twisting a rod. A few years later, French physicist Denis Papin designed and built two submarines consisting of a heavy metallic box and air pump. When enough air was pumped inside, the operator could open holes in the floor of the sub to let in enough water to float the box. Papin reportedly tested a second, oval-shaped vessel on the Lahn River in 1692. There were also reports of Ukrainian Cossacks employing a submersible boat, much like a modern diving bell, that they propelled by walking beneath it on the bottom of the river.

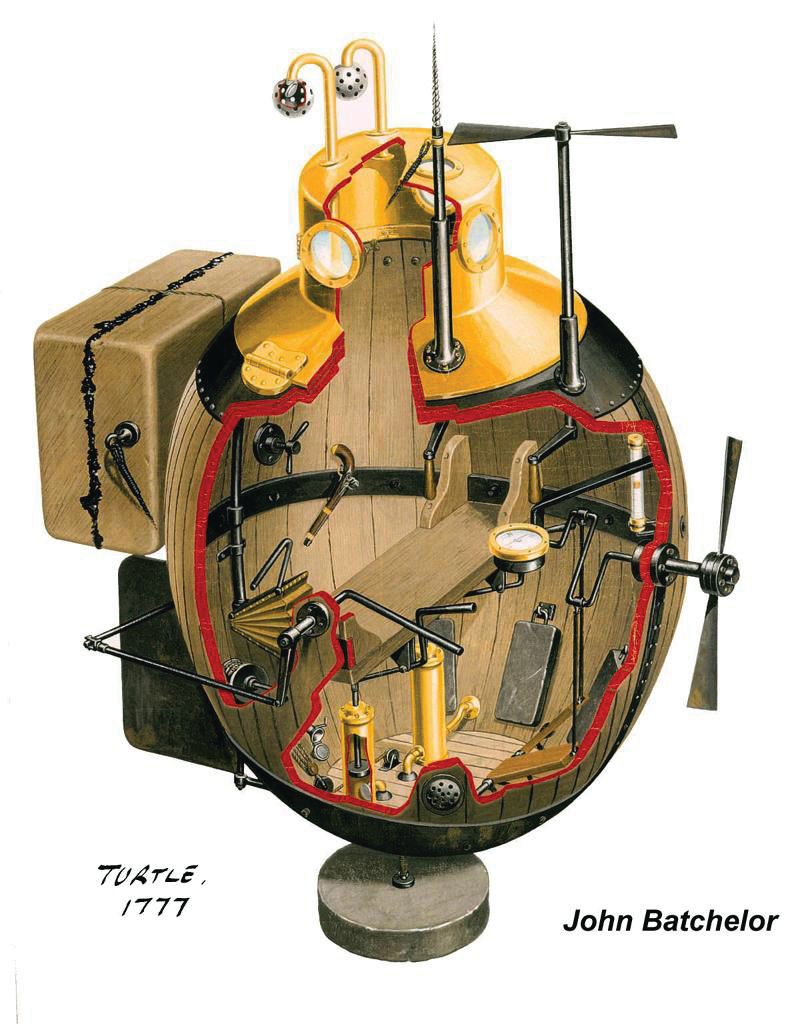

The Turtle: The First Military Submarine

The first military submarine was Turtle, which made its debut during the American Revolution. Built in 1775 by Connecticut inventor David Bushnell, the walnut-shaped submersible measured 7 feet high and 5½ feet wide. Bushnell designed it to be operated by one man and capable of submerging 20 feet deep for up to half an hour. Made of oak and covered with pine-tar pitch for waterproofing, Turtle looked more like a beer keg than a modern submarine. The ship dove and surfaced by means of brass pumps that took in or expelled seawater as ballast, while using 700 pounds of lead weights that could be played out in 50-foot increments on a line.

Following the outbreak of the American Revolution, patriots were desperate to strike a blow at British ships blockading New York harbor. Bushnell’s Turtle was pressed into service. To sink the British ship Eagle, Turtle would need to come alongside and fasten a 150-pound bomb to Eagle’s keel with a screw. Bushnell initially gave the piloting job to his brother, Ezra, but Ezra’s poor health led to the postponement of the plan. In the end a sergeant in the Continental Army, Ezra Lee, was chosen for the task. On September 6, 1776, Lee set out on the mission. Unfortunately for the Americans, he could not drill a hole into Eagle’s copper-reinforced bottom, and the attack failed.

The Submarine Takes its Iconic Shape

In 1801, expatriate American designer Robert Fulton, then living in France, demonstrated the copper-hulled Nautilus, the first fish-shaped submersible, which employed a screw to push rather than pull the vessel. The vessel included sails for surface propulsion and enough compressed air to keep a four-man crew underwater for three hours. In spite of successful trials on the Seine River in Rouen and at Brest, the French Admiralty declined to invest in Fulton’s new technology.

In the 1850s, the Danes were at war with the German states, and the Danish Navy blockaded German ports. A Bavarian artillery engineer, Wilhelm Bauer, devised a plan to utilize submarines to attack the Danish ships. With public support, he built Brandtaucher (Fire Diver). Disaster struck when the hull plates sprang a leak, and the ship sank to the bottom and became embedded in mud. Bauer persuaded his men to let the water flow in, equalizing the pressure inside and outside the submarine to enable the hatch to be opened. After six long hours underwater, the crew was able to flee its doomed vessel. Bauer did not give up. In 1856 he built Seeteufel (Sea Devil), a 52-foot submarine carefully equipped with a rescue device, for Russia during the Crimean War.

Submarines of the Civil War

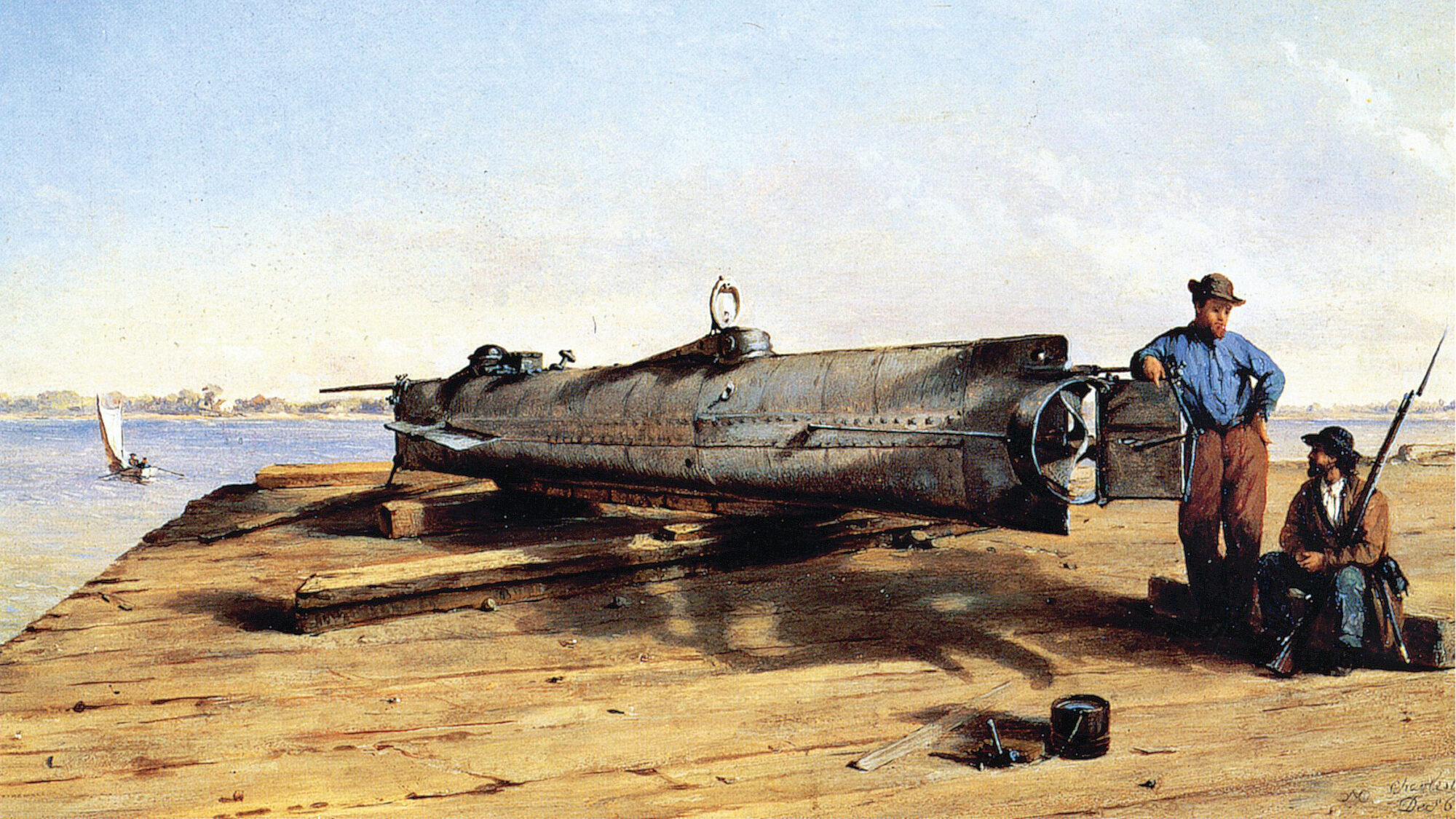

Confederates tried their hand at submarines during the Civil War. In 1861, New Orleans-based machinist James McClintock built Pioneer, a cigar-shaped vessel with conical ends, 30 feet long and four feet in diameter. Pioneer was built with countersunk rivets to join quarter-inch iron plate to its interior framework. This reduced friction while she moved underwater. During a subsequent test run, Pioneer successfully sank a schooner on Lake Pontchartrain.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, the Union Navy soon took New Orleans, and one of the financial backers of the submarine, Horace L. Hunley, ordered Pioneer scuttled to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. Hunley did not give up. He built another vessel, Pioneer II, or American Diver. He set out to sink a blockading Union ship, but a squall blew in from the sea. While being towed by a tug, the submarine sank after a big wave swept over its open hatch.

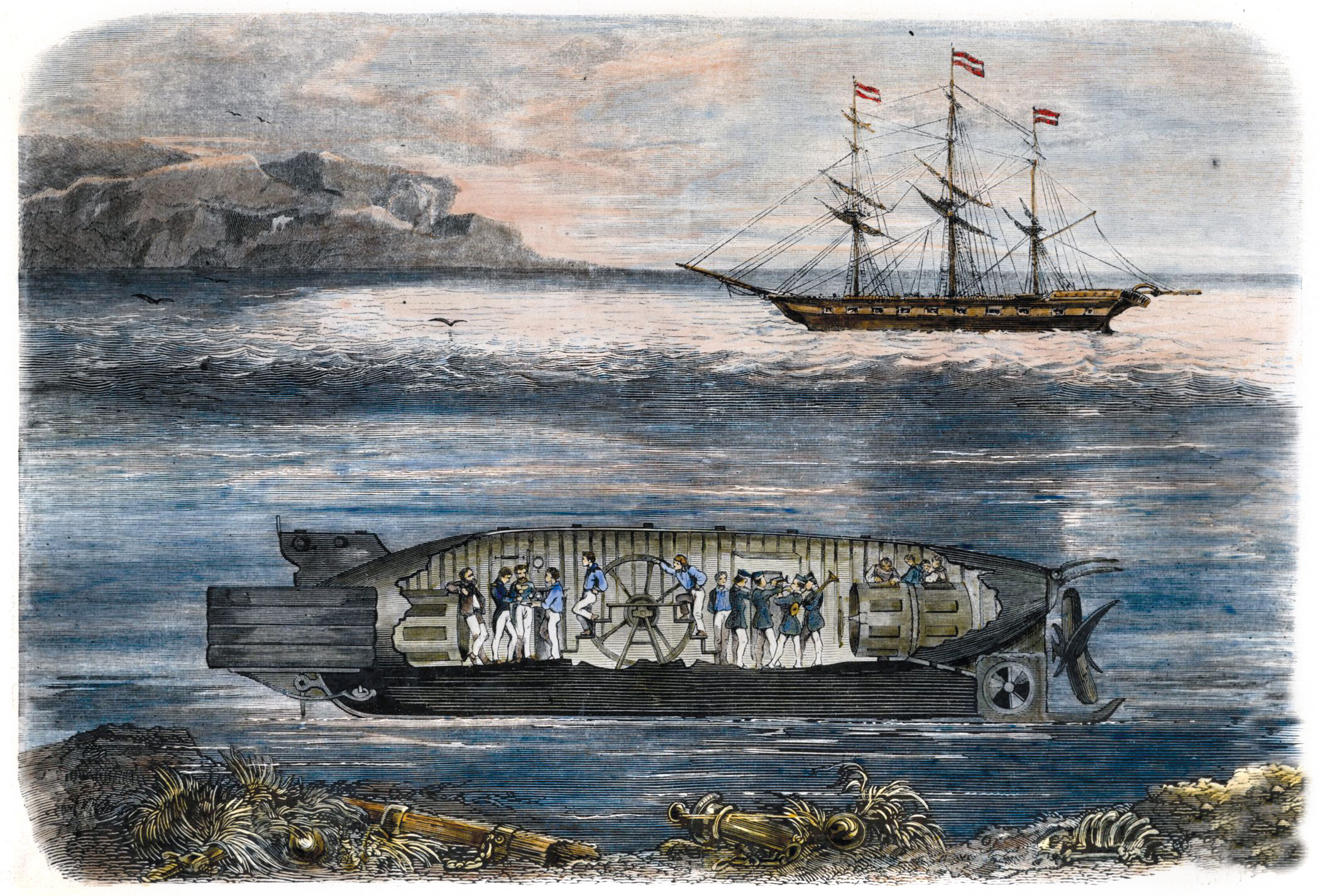

The determined Hunley built a third submarine, named after himself. The Horace L. Hunley was more advanced than its predecessors. Built from a boiler, the vessel had diving plates on each side of the hull, manual pumps to increase or decrease water ballast, and a single screw and rudder. The submarine had a snorkel for air and was equipped with a 90-foot-long spar loaded with black powder. A crew of eight hand-cranked the propeller shaft. Three crews were lost while testing the vessel in Mobile, including Hunley himself.

The submarine was raised, re-outfitted, and transferred to Charleston, South Carolina. On the night of February 17, 1864, Hunley set out to sink the Union warship Housatonic, anchored 12 miles outside Charleston harbor. The sub came up to the enemy vessel to attach the charge. While attempting to back away, Housatonic inadvertently rammed Hunley, setting off the bomb. In a matter of minutes, Housatonic sank. Unfortunately for the crew aboard Hunley, so did the sub.

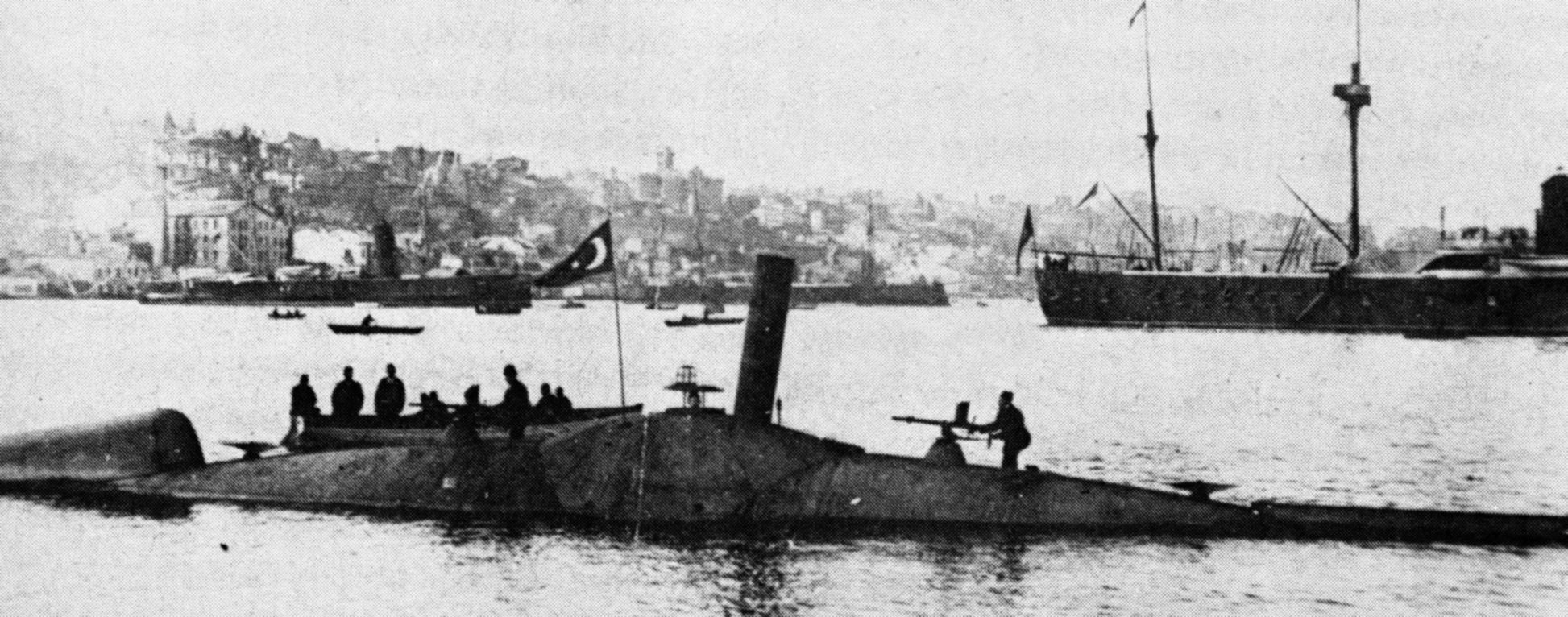

Early in the 1880s, George Garrett, an English clergyman, and Thorsten Nordenfeldt, a Swedish inventor, teamed up to build the first steam-powered submarines. Nordenfeldt III, their best, could submerge to a depth of 50 feet for a range of 14 miles. A steam engine powered the submarine on the surface and was shut down to dive. Nordenfeldt III also had twin torpedo tubes. Sold to the Ottoman Navy, Nordenfeldt III later had the distinction of firing the first underwater torpedo.

The Arms Race of the Early 20th C.

In 1889, an officer in the Spanish Navy, Don Isaac Peral, designed a more advanced submarine. Named after himself, Peral’s ship was entirely powered by electricity and made of steel. Peral was capable of 10 knots on the surface and eight knots submerged. In many respects, Peral resembled the submarines later developed during World War I. It had two torpedoes, fresh-air systems, and a fully reliable underwater navigation system. Despite two years of successful tests, the hidebound Spanish Navy terminated the project—a lucky break for the United States Navy, which would go to war with the Spanish nine years later.

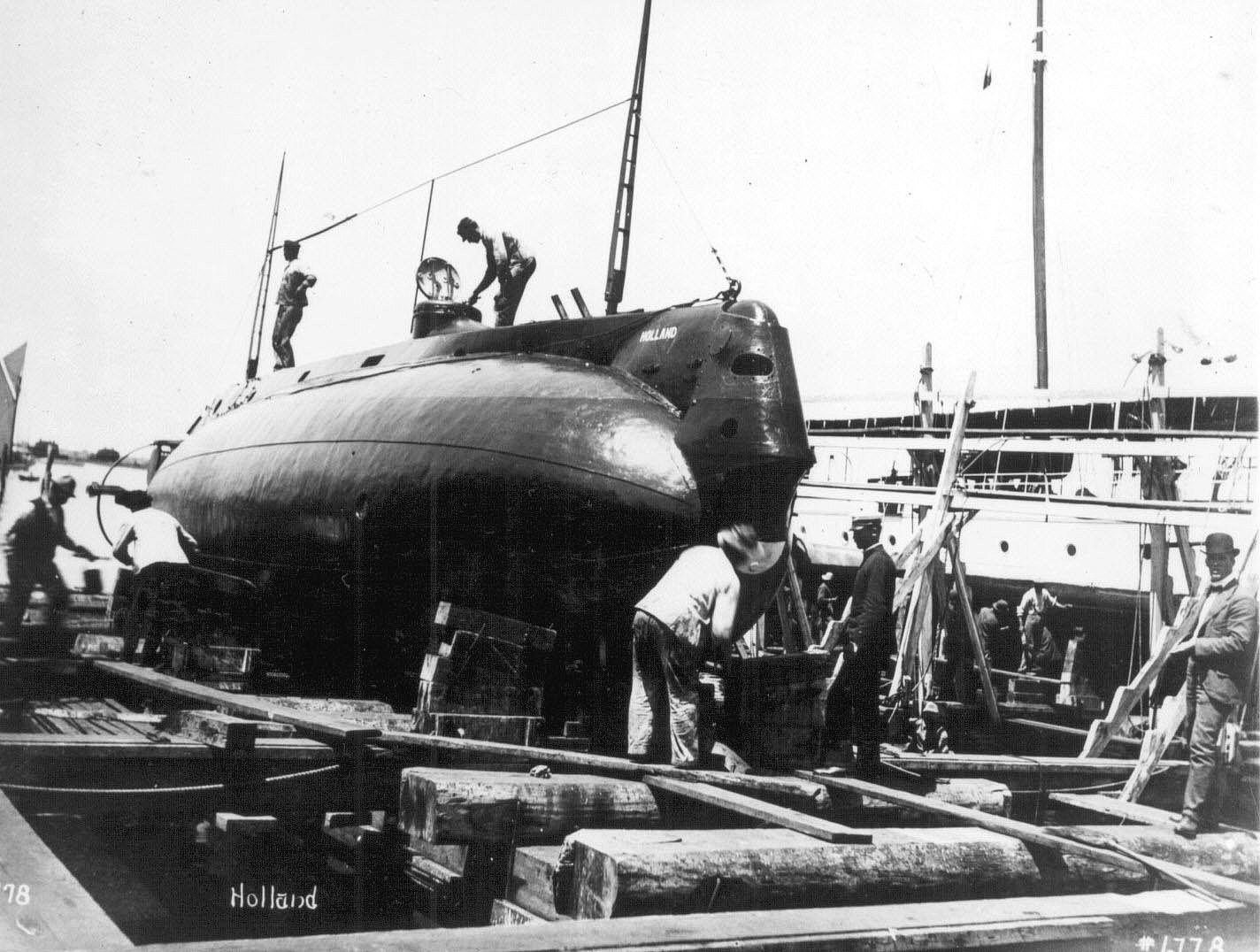

Americans became involved in the development of the submarine during the last few years of the 19th century. Irish inventor John Philip Holland built America’s best-known practical submarine, Holland. A gasoline engine powered the submarine on the surface, and a battery-driven motor did so when the vessel was submerged. Holland could fire 18-inch torpedoes from a single torpedo tube. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt witnessed the sub’s sea trials and recommended that the Navy buy Holland, but it was not until 1900 that it was formally commissioned. Six more submarines of the Holland type were ordered. Holland’s company later filled orders by Great Britain, Russia, the Netherlands, and Japan. The Holland Torpedo Boat Company was the forerunner of General Dynamics, which continues to build sophisticated submarines today.

Another pioneer in the development of the submarine was Simon Lake. In 1894, Lake launched the first practical submarine in the rivers of New Jersey. The following year, the Lake Submarine Company began to build the first steel submarine, Argonaut I. Lake’s submarines had the first bow and stern diving planes for depth control. In 1897, he patented the “even-keel” submarine. Lake developed the periscope and virtually eliminated the magnetic effect of metal surrounding the submarine’s compass. In 1898, Argonaut completed a 1,000-mile cruise above and beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean.

During the early part of the 20th century, Great Britain and Germany were engaged in a naval arms race. Both sides placed emphasis on battleships and other surface ships. Nevertheless, the two countries also constructed submarines. Typical of these submarines was Germany’s U-20, which would infamously sink the British liner Lusitania. U-20 displaced 650 tons running on the surface and 837 tons submerged. Two eight-cylinder diesel engines capable of 15 knots powered it on the surface, and two electric motors provided up to nine knots when submerged. U-20 carried an 88mm deck gun and seven torpedoes similar to the Whitehead torpedo developed by an English inventor of that name. The torpedoes were 12 to 16 feet long and weighed about a ton. Air driven, they could travel up to 40 knots for the first 1,000 yards with a warhead of 290 pounds of trotyl explosive.

World War I: The Strategic Impact of Submarines

The submarine proved its value early in World War I. On September 22, 1914, three obsolete British cruisers, Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy, were sunk by a single German submarine, U-9. Of the nearly 2,300 men aboard the cruisers, more than 1,400 were lost. U-9 sank the three cruisers with an expenditure of only six torpedoes.

The most notorious victim of a submarine during World War I was the Cunard Line’s Lusitania. On May 7, 1915, she was off Old Head, near Kinsale, Ireland, when she encountered U-20. With a single torpedo the German submarine sank the liner with the loss of more than 100 American passengers. This was doubly shocking since up to that time it was believed that any ship traveling faster than 15 knots was immune from submarines. Lusitania was going 18 knots when she was torpedoed.

A few months later, U-24 torpedoed and sank the passenger liner Arabic of the White Star Line. The Woodrow Wilson administration put pressure on Germany to refrain from sinking any more passenger liners. Germany agreed not to sink the liners unless they resisted—the so-called Arabic pledge. The following year, however, a German submarine torpedoed and damaged a ferry boat, Sussex. Germany restated her vow not to sink passenger liners.

German U-boats became larger and more powerful as the war progressed. One such example was U-53. This submarine was more than 200 feet long and carried two medium-caliber deck guns, with a range that was a great deal farther than its predecessors. On October 7, 1916, U-53 surfaced on the East Coast of the United States. Eventually, U-53 sank four ships off the American homeland. Since the sub was operating in international waters, the United States Navy could do nothing but protest ineffectually against the attacks.

A few months later, Germany announced that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. Any ship, including American vessels, would be sunk if they tried to go to or from Great Britain. This ill-conceived policy brought the United States into the war on the Allied side and fatally tilted the conflict away from Germany, whose submarine warfare proved decisive—for the wrong reasons.

The Interwar Japanese Submarine Fleet

During the interwar years, Japan developed a varied submarine fleet. Some carried aircraft, others cargo. Many were equipped with the most advanced torpedo of the war, the oxygen-propelled Type 95, nicknamed “Long Lance.” The size of Japanese submarines varied. Some were midget submarines with one-man crews and an 80-mile range. Others were medium- or long-range subs with the fastest submerged speeds of the war. Because of the Imperial Navy’s decision to attack enemy warships instead of merchant ships, Japanese submarines proved largely ineffective, sinking less than one-fourth as much merchant shipping as the submarines of the U.S. Navy. The lack of radar also hampered Japanese submarine warfare efforts.

World War II Submarine Warfare

When Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in the 1930s, he rebuilt the German Navy and ordered the construction of new U-boats to replace the 360 subs sunk or surrendered during World War I. When World War II broke out, the German submarines adopted new tactics, traveling in “wolf packs” to attack Allied convoys. The British had reintroduced the convoy system, installing radar on their ships and using high-frequency direction finders to locate the signals of the enemy submarines. Unbeknownst to the Germans, the British broke their code, allowing the British to know when and where German submarines would strike.

German submarines became larger and faster. In 1940 the Nazis developed U-300, a streamlined 550-ton vessel capable of reaching 19 knots when submerged. In July1942, German engineers scrapped U-300 and came up with U-301. In the end, only seven subs of this type were completed; an additional two were near completion before being damaged in an Allied air raid.

American submarine efforts were much more successful in World War II. A total of 314 subs served in the United States Navy. Fifty-two were lost during the war, with 41 of the losses directly attributable to enemy attacks. A total of 3,506 American submariners were killed in the war. In return, American subs devastated Japanese shipping, sinking more enemy supply ships than all other weapons combined, including aircraft.

Entering the Nuclear Age

After the war, the United States and the Soviet Union raced to build better submarines during the Cold War. Out of this came the nuclear-powered submarine, which could stay submerged longer and had a much longer range than World War II-era subs. Both sides placed ballistic missiles aboard submarines. These vessels carried long-range missiles with nuclear warheads. In 1955, Nautilus became the first nuclear-powered submarine. Advances in technology, including equipment that could extract oxygen from sea water, allowed the subs to remain submerged for weeks or months at a time. Three years later, Nautilus completed the first voyage beneath the Arctic ice cap.

Two American nuclear submarines, Thresher and Scorpion, were lost to equipment failures during the Cold War, while the Soviet Union lost at least four subs, including Komsomolets, which held the depth record among military submarines of 3,000 feet. Komsomolets sank in April 1989 in the Barents Sea off Norway after a catastrophic fire aboard ship. A total of 42 Russians died in the frigid waters.

Most of the wars since World War II have been land wars, with submarines playing little part in them. However, in 1982 Argentina seized the Falkland Islands off the Argentine coast. Great Britain responded by dispatching elements of the Royal Navy to the South Atlantic, blockading the islands with submarines. During the war, the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS Conqueror. The cruiser was sunk, and 368 men were lost. It was the largest loss of life during the entire war. General Belgrano had the unwanted distinction of being the first (and so far only) ship sunk by a nuclear-powered submarine.

The modern submarine is a deadly weapon. From a leather-covered, 12-oar rowboat to a vessel armed with nuclear warheads capable of wiping out entire civilizations, the submarine has made great strides militarily. Perhaps da Vinci was right to fear “the evil nature of men who practice assassination at the bottom of the sea.”

The General Belgrano was the former USS Phoenix. She survived the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor and served the US Navy with distinction throughout the war.