By Roy Morris Jr.

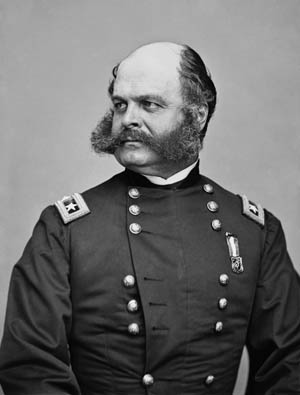

Nothing in Ambrose Burnside’s pre-Civil War career indicated that he would be anything but a successful and energetic general. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Class of 1847, he had served in the Mexican War and on the southwestern frontier, being wounded during a skirmish with Apaches. He was well liked and well considered by his superiors.

The first hint of trouble came after Burnside resigned his commission in 1853 to open a munitions factory in his native state of Rhode Island. He intended to manufacture a new breech-loading carbine he had personally designed. The Burnside carbine was a short rifle with no fore stock that fired a .54-caliber metallic cartridge—the first American firearm to use such a round.

A Major General in the Rhode Island Militia

The success of Burnside’s Bristol-based enterprise depended entirely on receiving a government contract. But despite producing and selling 200 of the weapons to the Army, he failed to secure the expected contract. As a consequence, he was forced into bankruptcy, with creditors assuming control of the carbine’s patent. Eventually, some 55,000 Burnside carbines were sold to the government, along with millions of rounds of metallic ammunition. Burnside did not receive a penny of the profits.

The success of Burnside’s Bristol-based enterprise depended entirely on receiving a government contract. But despite producing and selling 200 of the weapons to the Army, he failed to secure the expected contract. As a consequence, he was forced into bankruptcy, with creditors assuming control of the carbine’s patent. Eventually, some 55,000 Burnside carbines were sold to the government, along with millions of rounds of metallic ammunition. Burnside did not receive a penny of the profits.

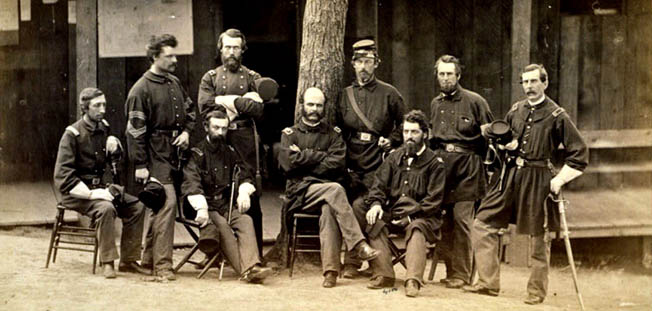

When the Civil War began, Burnside, then a major general in the Rhode Island Militia, was named a colonel of the 1st Rhode Island Volunteers, a 90-day regiment he had helped organize. Rushing to the nation’s capital, he fought competently at the First Battle of Bull Run and was promoted to brigadier general.

In the spring of 1862, Burnside led an expedition down the coast of North Carolina, capturing Roanoke Island, New Bern, Beaufort, and Fort Macon, despite being threatened with mutiny several times by the men in his combined Army-Navy invasion force and almost drowning off the coast of Cape Hatteras.

The Battle of Antietam

At the Battle of Antietam, Burnside needlessly delayed his arrival on the battlefield by fretting over the construction of a stone bridge across Antietam Creek. The picayune bridge-building prevented his friend McClellan from crushing Robert E. Lee’s Confederates and perhaps winning the war outright. Adding insult to injury, the bridge proved entirely unnecessary—the water in the creek was only knee deep.

Twice Lincoln offered Burnside command of the Army of the Potomac, and twice Burnside turned him down. Lincoln’s offers were both personal and political. He genuinely seemed to like Burnside, and he also wanted to soften the blow of removing the popular McClellan by replacing him with his best friend.

Finally, in November 1862, Burnside accepted the president’s offer and began making plans to attack Lee at Fredericksburg, Virginia. His plan depended heavily on surprise, but Lee was waiting for Burnside with his full army on Marye’s Heights when the Union attackers swarmed through the city on December 13. Wave after wave of Union attackers rushed the entrenched Confederate position, only to be decimated by massive rifle and artillery fire. Burnside muttered in anguish, “Oh, those men, those men.” More than 12,000 casualties were inflicted by Lee’s soldiers, at a cost of less than half that number.

“Burnside’s Mud March”

Following an ill-fated flank march that became infamous as “Burnside’s Mud March,” Burnside was mercifully removed from command and transferred west to the Department of the Ohio. He returned in time to lead the IX Corps in the various battles of Ulysses S. Grant’s Wilderness campaign before coming to grief in the rubble of the Crater.

Grant pronounced a harsh, if fair, judgment of Burnside’s career: “An officer who was generally liked and respected, he was not fitted to command an army. No one knew that better than himself.” Burnside had tried twice to tell Lincoln that very thing. It was too bad for everyone involved that the president had failed to believe him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments