When an Israeli tribunal found Adolf Eichmann, the right hand of Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich, guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against Poles, Gypsies, and Slovenes, and membership in the Nazi Gestapo, SS, and SD—all three deemed criminal organizations by the Free World—he remained obstinate.

Despite the fact that Eichmann implemented and carried out the directive for the systematic extermination of European Jewry as outlined at the infamous Wannsee Conference in 1942, he denied responsibility and stunned those present in the courtroom as he maintained that he was only following orders. “I cannot recognize the verdict of guilty,” he said.

Eichmann was, in essence, the executioner of hundreds of thousands of innocent people. Although he never directly killed anyone, he was responsible for issuing orders that led to the deaths, orders issued under the authority of his superiors. Eichmann packed the rail cars with human cargoes. His directives led to the deplorable conditions of the concentration and death camps that were wracked with starvation and disease.

Still, he asserted, “I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel guilty myself.”

On January 27, 2016, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Israel released Eichmann’s handwritten appeal of his death sentence that was handed down on December 15, 1961, and ultimately carried out a few minutes after midnight on June 1, 1962.

According to the distorted worldview that Eichmann held, he concluded that the trial judges had “made a fundamental mistake in that they are not able to empathize with the time and situation in which I found myself during the war years.”

Eichmann had also written to Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, president of Israel at the time, “It is not true … that I myself was a persecutor in the pursuit of the Jews … but only ever acted by order of [others].”

Amazingly, in his written appeal the war criminal who never rose above the SS equivalent rank of an army lieutenant colonel alludes to the “unspeakable horrors which I witnessed,” and goes on to relate, “I detest as the greatest of crimes the horrors which were perpetrated against the Jews and think it right that the initiators of these terrible deeds will stand trial before the law now and in the future.”

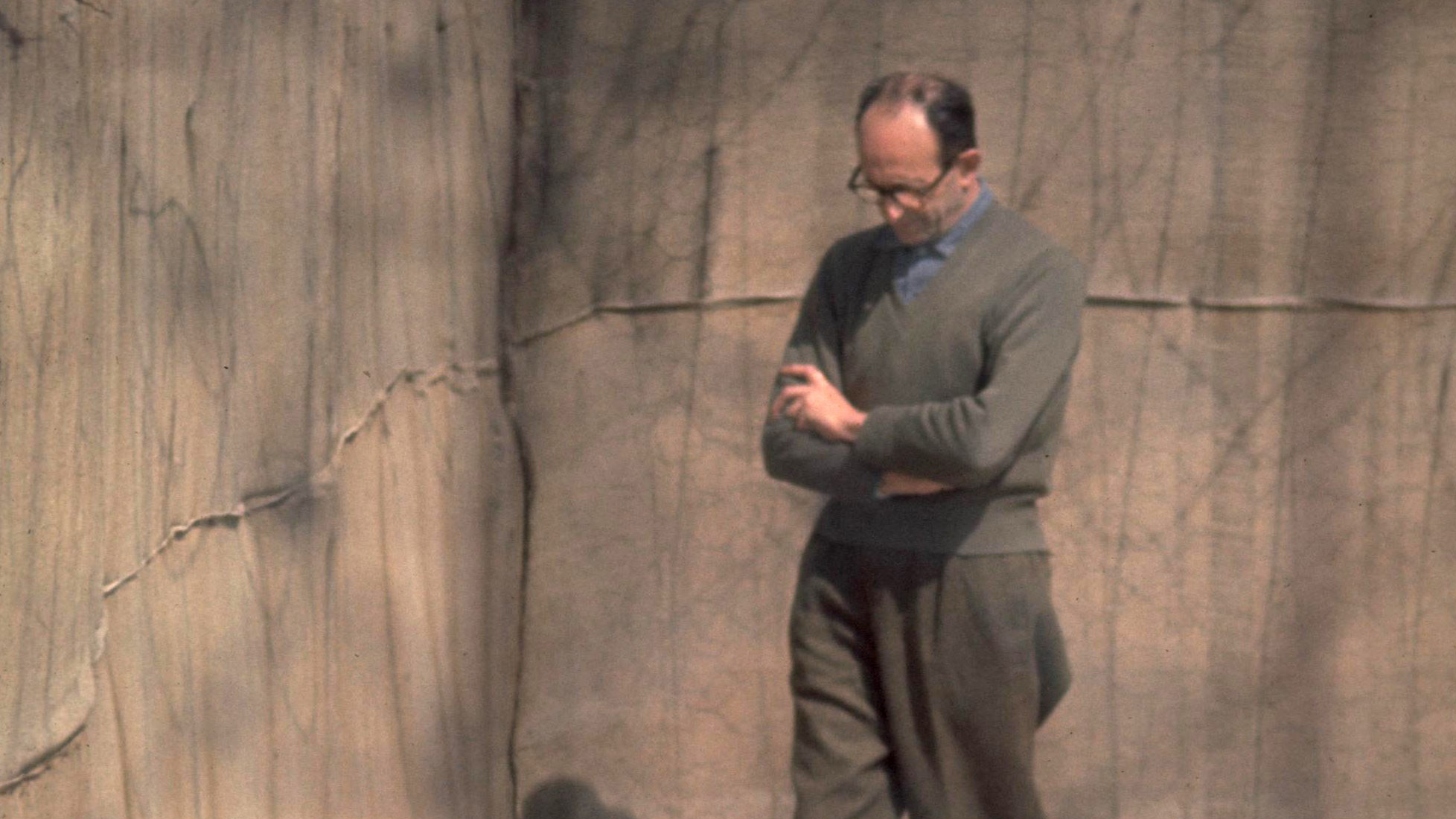

After hiding in Argentina and living under an assumed name until Mossad agents captured him on a street in Buenos Aires on May 11, 1960, and spirited him back to Israel for a trial in which the prosecution spent 56 days and called 112 witnesses in presenting its case, the bespectacled former SS officer appeared frail, merely a shadow of the Nazi strongman who wielded the proxies of the highest ranking officers in the SS.

In a statement issued with the release of the Eichmann appeal documents, current Israeli President Reuven Rivlin commented, “Not a moment of kindness was given to those who suffered Eichmann’s evil—for them this evil was never banal; it was painful; it was palpable. He murdered whole families and desecrated a nation. Evil had a face, a voice. And the judgment against this evil was just.”

More than simply an interesting footnote to the violent history of the Nazi era and the human tragedy of the Holocaust, Eichmann’s appeal reveals how totally and completely an individual may rationalize any action, no matter how heinous. Such a possibility is, in this case, chilling.

In the end, it is true that no human being can ultimately hide behind the weak defense of only “following orders” when those orders involve activities that civilized people must acknowledge are criminal in their very nature.

A lesson? Let it be so. Certainly a reminder.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments