By David Dean Barrett

More than seventy years after the fact, the use of atomic bombs by the United States in the final days of World War II remains one of the most controversial events of the 20th century. During his speech announcing the destruction of Hiroshima by an atomic bomb, U.S. President Harry S. Truman used the phrase, “Rain of Ruin.” However, by changing, “Rain” to “Reign” the quote can describe Hirohito’s time as emperor of Japan and the government that ruled the country during this period, because it was the actions of those leaders that ultimately caused the ruin of Japan.

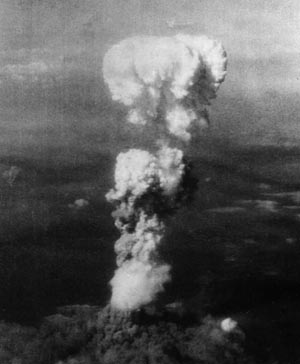

Hiroshima, Japan, August 6, 1945, 8:15 am local time: Two glimmering silver Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers fly high above the city about half a mile apart; a third circles several thousand yards away. The lead aircraft carries the number “82” on its fuselage, a large black R encircled on its tail, the name Enola Gay on its nose, and the atomic bomb Little Boy in its belly.

The doors to the forward bomb bay open, and a large gun-metal gray projectile falls out, bottom first, flips over, and hurtles nose down toward the metropolis below. With the abrupt loss of weight the plane lunges upward, then banks violently to the right, noses down, and accelerates away as fast as its four 2,200-horsepower radial engines will drive it.

The city below is serene, an azure blue sky above it. People are engaged in their daily routine: adults going to work, children to school. It is morning rush hour. Residents pay no attention to such a small group of American planes.

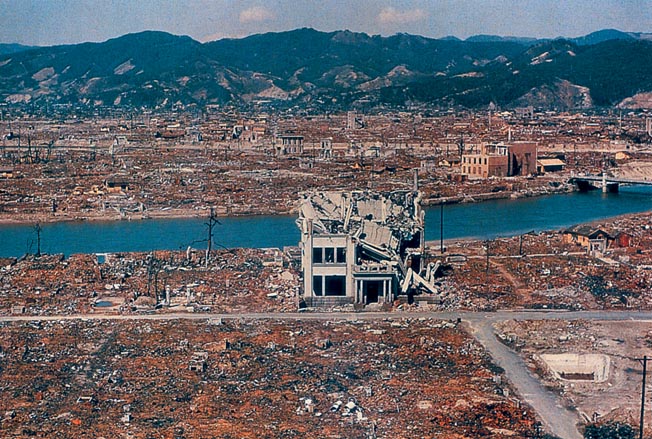

The bomb drops for 43 seconds before exploding 2,000 feet above the ground in a pinkish burst that cuts across the sky. A fireball—a football field in diameter—erupts from the flash without a sound. An iridescent bolt of light strikes the ground. The heat from the blast melts the surface of granite within a thousand yards of the hypocenter. Roof tiles soften and change color from black to olive or brown and are ripped off. A huge mushroom cloud, filled with every color in the rainbow, ascends five miles above the ground.

Over the center of the city silhouettes are burned onto walls and the street, as people are instantly vaporized. A mile from the epicenter, thousands of Japanese soldiers doing morning calisthenics on the military base drill grounds are instantly roasted to death.

A supersonic blast of wind tears across Hiroshima in a concentric ring for two miles, demolishing all but a few earthquake-proof buildings. People are picked up, blown through the air, and smashed against anything still upright. Some are transformed into grotesque carbon statues and litter the ground like leaves fallen from a huge tree.

The city becomes pitch black, silent. Gradually the blackness dissipates like fog and gives way to gray. Zombie-like figures slowly slog through the ruined city; their shredded and burned skin hangs from them. A woman carries a baby with no head. Fires burn everywhere. Dead bodies glut the river and litter the ground; many are nothing but skeletal bones. Children cry for their mothers. Black rain begins to fall.

Three days later the same fate befalls Nagasaki. Such grim descriptions call to mind concern mainly for the suffering and hardship of unsuspecting Japanese civilians. While their torment was unquestionable, such a singular view argues that the effects of the atomic bombs render their use indefensible.

However, to completely understand the decision to use such weapons requires a thorough examination of the historical context of both the use and effects of the bombs. The war engendered hardship on both sides of the battlefield, diplomatic intransigence, and Japanese abuses of power.

There were five principal topics in the last year of the war that need to be considered: unconditional surrender; the Japanese strategies of Spirit (at the start of the war) and Defense in Depth (in 1944); the escalation of the war; the Japanese wartime government; and, finally, the key decisions made by the leaders in both Japan and the United States during the final months of the war.

Unconditional surrender means quite simply that the defeated state agrees to whatever the victor decides. It is the equivalent of a revolution for the vanquished nation because its primary objective is the removal of the government in power. Most conflicts have not and do not end in this fashion; instead, they are concluded by negotiation between the belligerents and the establishment of mutually acceptable, if not desirable, terms or conditions. While the Allies’ demand for unconditional surrender during World War II was not unprecedented, it was unusual, and it grew out of an American initiative for a specific reason.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt first considered the idea of forcing the Axis nations to accept unconditional surrender in the spring of 1942. Almost a year later, in January 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill formalized this intention into official policy at their meeting in Casablanca. When he was later asked why the Allies were demanding unconditional surrender, Roosevelt replied, “We are fighting this war, because we did not have an unconditional surrender at the end to the last one.” Thus the requirement’s genesis went all the way back to the armistice that ended World War I and the Germans’ belief that they “weren’t defeated”—a belief that angered Germany, spawned Hitler, and led to a second world war.

FDR continued to reinforce the demand for unconditional surrender over the next couple of years. At a press conference in July 1944, Roosevelt stated, “Practically all Germans deny the fact that they surrendered during the last war, but this time they are going to know it, and so are the Japs.”

After Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945, Truman inherited the legacy of unconditional surrender. Just four days later, during his first address to a joint session of Congress, he too called upon all Americans to support him in carrying out the ideals for which Roosevelt lived and died—and the first of these was unconditional surrender.

The ongoing buttressing of this war aim among the Allied nations caused one historian to state, “If the Americans had made the first move toward peace with the Japanese, Stalin would have denounced it as a treacherous attempt to negate a part of the Yalta Agreement, specifically Stalin’s commitment to enter the war against Japan 90 days after Germany’s surrender, by striking a deal before Russia entered the war.”

This comment is grounded on an enticement made at Yalta by Roosevelt, specifically to allow the Soviets to take possession of southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, internationalize the port of Darien, and restore the Soviet lease on Port Arthur.

As an aside, neither Germany nor Japan took opportunities to negotiate an end to the war. The former had an occasion—with France and Britain in the late winter and early spring of 1940, and again with Russia in 1942-1943—and did nothing. Japan could have considered ending to its war with China in the late 1930s and chose not to.

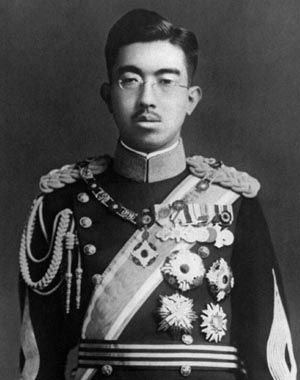

During World War II, the Japanese government was fundamentally a military oligarchy. It was made up of three components: the emperor, considered divine; the prime minister, appointed essentially by the emperor; and the prime minister’s cabinet, partially chosen by him and partially by the incumbents—explicitly the Chiefs of the General Staff of the Army and Navy. The latter augmented the military’s power and influence considerably because it allowed them to place the most hawkish members of their respective services into these positions.

Decisions made by the prime minister and his cabinet had to be unanimous. This meant any dissenter had the effect of a veto vote; this created a dysfunctional government. Whenever a unanimous decision could be reached, it was presented to the emperor for his approval, which was largely a rubber stamp.

As such, the emperor knew and agreed to the decisions being made but did not exercise his power in the same fashion as a traditional monarch. However, in extraordinary circumstances he could be asked to make his opinion known to the members of the cabinet, and, because of his divinity, he could provoke a binding decision.

Three prime ministers led Japan during the Pacific War: Hideki Tojo (October 18, 1941-July 22, 1944), Kuniaki Koiso (July 22, 1944-April 7, 1945), and Kantaro Suzuki (April 7, 1945-August 17, 1945).

The last of these, a retired admiral, guided the country primarily with five other men: Army War Minister Korechika Anami, Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, Army Chief of Staff Yoshijiro Umezu, Navy Chief of Staff Soemu Toyoda, and Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, the only civilian. The group was referred to as “The Big Six” or the “Supreme Council at the Direction of War.”

Virtually all Japanese leaders lived in mortal fear. Assassination of political and military leaders had become commonplace in Japan beginning with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In the 27-year period from 1909 to 1936, eight members of the government and military, including five prime ministers, two generals, and an admiral, were murdered. The message from junior officers, the most frequent perpetrators of these murders, was clear: either support a politically aggressive ideology or you risk your life.

The word bushido, used to describe the fighting spirit and behavior of Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen during the Pacific War, was a perversion of its historic meaning. Bushidorefers to the “way of the warrior” and is further defined as “a hybrid code of ethics refined from both the deep honorable tradition of the Japanese warrior class and the spiritual wisdom of Buddhism and Confucianism.”

Thus, the application of the Bushido Code had less to do with war, pride, power, and conquest and more to do with a path to human refinement, and for some, enlightenment.

The roots of bushido are firmly planted in a serious and structured approach to living rightly, even if that meant dying for the achievement of living by the code. This is why seppukuor harakiri (suicide by disembowelment) became an accepted practice in Japanese culture for hundreds of years. It was thought that maintaining the honor of oneself or the family was paramount to all else, including one’s own life.

The eight accepted elements of bushido are: rectitude, courage, benevolence, respect, honesty, honor, loyalty, and self-control.

In the 20th century, Japanese militarists hijacked the code and reduced it to little more than courage and loyalty. Combining this version of bushido with an obligation to die for the emperor, military leaders instilled absolute obedience in their subjects.

Japanese servicemen did indeed exhibit courage and loyalty throughout the war, but nothing in their conduct resembled the other six elements of bushido (save a perverted sense of honor), as they behaved in some of the most sadistic and barbaric ways imaginable toward both their battlefield enemies and the people living under Japanese occupation.

From 1931 until the spring of 1944, the Japanese military doggedly held to an idealistic belief that the “spirit” of its soldiers was superior to that of any of its enemies and would result in victory on the field of battle. In combat this meant that, while artillery, mortars, and machine-gun fire would be used tactically to soften up an adversary, bayonet charges and hand-to-hand combat would ultimately defeat them.

This concept of military strategy showed some success in Japan’s war with China and the early stages of World War II. However, against the United States beginning in the summer of 1942, it ran into a wall of lead and steel the likes of which the Japanese had never experienced. Banzai charges became little more than a death sentence for the Nippon soldiers facing overwhelming American firepower.

Worse still, the failed charges often led to major breakthroughs that were exploited by the Americans to win the battle. But Japanese military leaders stubbornly clung to the approach for two more years.

Finally, in the spring of 1944, Japan adopted a new stratagem, albeit no less onerous for its troops. Believing American morale to be brittle and that with enough casualties they could still win something better than unconditional surrender, the Japanese embraced the strategy of “Defense in Depth.”

Defense in Depth requires the defender to deploy his resources, such as fortifications, field works, and military units, at and well behind the front lines. Although an attacker may find it easier to breach the more weakly defended front line, as he advances he continues to meet increasingly stiff resistance. The deeper he penetrates, the more his flanks become vulnerable, and if the advance stalls the attacker risks being enveloped.

Japanese military planners went even further, adding their own unique spin to this scheme. From the inception of their training, Japanese troops were indoctrinated with the belief that it was dishonorable to surrender and that they had a duty to die for their emperor.

Knowing this axiom, expedient battlefield commanders rationalized the use of tactics that ignored the possibility that their troops might need to retreat. Because battles were often fought on islands, the defenders could literally dig into the volcanic or coral landscape, where it was virtually impossible for an attacker to bypass or flank their fortified positions.

The result was indeed a formidable defense, which imposed ever higher casualties on the Americans. It remained to be seen whether American morale could be broken in this manner.

The last year of the war was far and away the bloodiest for American forces; 64 percent of all the casualties and 53 percent of battle deaths occurred during this time. This happened partially because of the strategy of Defense in Depth and partly because of the progressively larger land, sea, and air battles being fought.

The campaign to seize the Marianas Islands in the Central Pacific is a case in point. It began with the invasion of Saipan on June 15, 1944, just nine days after the D-Day landings in Normandy, with an American task force of about two thirds D-Day’s size and more than 7,000 miles away. The assault offered dramatic proof of how American might had grown in the 21/2years since Pearl Harbor.

The combined operation encompassed Marine, Army, and some of the largest naval forces of the war. One historian observed, “The fuel needed for the battle would have powered the entire German war machine for a month in 1944.”

The battle to seize Saipan took 24 days and ultimately featured the largest banzai attack of the war early in the morning of July 7, when more than 4,000 Japanese soldiers stormed the American lines along the island’s northwest coast. When it finally ended at around six in the evening, all the attackers lay dead. But they had killed or wounded more than 1,000 Americans.

In the waters west of the Marianas between June 19 and 20, one of the greatest air-sea engagements of World War II—two to three times larger than the Battle of Midway—took place between the American and Japanese navies in the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

Also called “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” this two-day battle saw American aviators decimate their Japanese counterparts, shooting down 426 aircraft of all types or 90 percent of Japan’s striking force. The additional destruction of three of Japan’s fleet aircraft carriers forever ended her ability to use carriers to conduct offensive operations in the war.

The fall of Guam on August 10, the last of the Marianas Islands to fall, shattered Japan’s inner ring of defense. The conquest of the Marianas provided the United States with bases for its long-range, four-engine heavy bomber, the B-29. All three islands served as points of origin for the strategic bombing of the Japanese homeland—an offensive that began November 24, 1944—and would, in due course, include the 509th Composite Group stationed on Tinian, which would deliver nuclear weapons to its targets.

Once the United States had gained control of the Marianas and the seas surrounding them, American air forces quickly moved to cut off Japan’s industries from strategically vital oil, iron ore, and bauxite resources in the territories Japan occupied in Southwest Asia.

The victory also led to the termination of an ineffective and expensive China-based B-29 bombing campaign against Japan. Strategically, Japan had been defeated, but Japanese leaders, unwilling to accept unconditional surrender and still believing that they could cause massive American causalities when the home islands were invaded, refused to surrender.

But taking this strategic position in the Pacific came at a high cost. In two months of grueling island and naval campaigns, U.S. forces killed 60,000 Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen, while the Japanese inflicted just under 30,000 casualties on the Americans—5,500 of whom were KIAs.

In the months immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese took nearly 140,000 Allied combatants and more than 300,000 civilians as prisoners of war. By war’s end, an appalling 27 to 38 percent of the military prisoners had died in Japanese captivity compared to only two to four percent of those held in German camps. Those who did survive often looked as though they had come out of Nazi extermination camps. As early as 1942, it had become common practice for the Japanese to massacre prisoners, triggered by the mere threat of invasion by Allied forces.

On August 1, 1944, the Japanese formalized their policy toward Allied POWs. A “kill order” was sent to the commandants of all its POW camps. With the Allies advancing everywhere in the Pacific, the order made it clear the Japanese did not want any of the POWs in their possession to be repatriated. The order stated, “It is the aim not to allow the escape of a single one, to annihilate them all, and not to leave any traces.”

In December 1944, the Japanese massacred 139 American POWs held in the Philippine province of Palawan. The murders sparked a series of rescue missions, the most famous of which was “The Great Raid” in January that freed more than 500 Americans. But Allied prisoners remained in grave jeopardy until Japan surrendered.

As the time approached for invading the Philippines in late October 1944, Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific Command was tasked with securing Peleliu to protect General Douglas MacArthur’s flank from an airstrip on the island that potentially threatened his forces.

The Battle of Peleliu, September 15-November 27, 1944, on a tiny coral islet about 600 miles southeast of the Philippine island of Mindanao, became the first to test the potential of Japan’s strategy of Defense in Depth.

In preparation, Japanese defenders honeycombed Peleliu with bunkers, blockhouses, and pillboxes. Most of these fortifications tunneled into the island and all bristled with interlocking rings of rifle, machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire. The Japanese plan forced American Marines and soldiers into squad-level tactics at point-blank range to eliminate positions, all the time subjected to a murderous onslaught that created mountainous losses for the Americans.

Marine Corps commander Maj. Gen. William Rupertus had predicted that the battle would take three days. Instead, the ensuing slaughter to seize Peleliu’s six square miles raged for 73. Marines and soldiers suffered nearly 8,000 wounded and 2,000 dead. Japanese losses were nearly absolute—between 10,500 and 11,000 died.

No longer would large numbers of Japanese expose themselves in banzai charges against American forces. They would make their enemy blast them out of fixed fortifications—one bunker, one pillbox, or one cave at a time. The Defense in Depth strategy had proven its bloody effectiveness, and it would be employed with even greater sophistication during the last land battles of the Pacific War: Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, from October 23-26, 1944, was the largest naval battle in history. Three days earlier, on October 20, U.S. troops invaded the island of Leyte as part of an effort aimed at not only fulfilling MacArthur’s pledge to retake the Philippines, but to further isolate Japan from the countries it occupied in Southwest Asia.

Despite the desperate commitment of nearly all its remaining capital ships to the fight, the Imperial Japanese Navy suffered its heaviest losses of the war. Thereafter, the IJN posed no significant threat to the Allies. Its few remaining ships limped back to Japan and, deprived of fuel, remained there until the end of the war. Leyte Gulf claimed the lives of 3,000 Americans and more than 10,500 Japanese.

The battle for the Philippines was the largest and most protracted campaign of the Pacific War. The fighting continued until Japan’s surrender, generating 62,000 American casualties, of which 14,000 were KIA. Japan suffered a staggering 336,000 dead.

By November 1944, American engineers and Seabees had turned Guam, Saipan, and Tinian into colossal airbases. The initial phase of the bombing campaign against the Japanese home islands, which took advantage of the B-29’s speed and high-altitude capabilities, yielded poor results due in large part to the jet stream and the frequently cloudy weather over the country.

But everything changed shortly after General Curtis Lemay assumed control of the XX Bomber Command in January 1945, as he radically altered bombing tactics. Rather than sending his B-29s in high-altitude daylight attacks, he would send them in at night at much lower altitudes.

In a raid that will forever mark this turning point, on the night of March 9-10, 1945, Lemay ordered more than 300 B-29s, using a mix of incendiary cluster bombs and high-explosive bombs, to strike Tokyo. The attack caused an urban conflagration—a firestorm—and became the single most destructive aerial bombing raid of the entire war in all theaters. Nearly 250,000 homes were destroyed as 16 square miles of the city were incinerated. The death toll was estimated at between 80,000 and 100,000 people—more outright than either of the atomic bomb attacks.

Similar raids continued for the next several months along with the aerial mining of Japanese ports. By August, Lemay had few targets left as much of Japan’s war economy and about 60 percent of her major cities lay in ruins.

The February 19-March 26, 1945, battle for Iwo Jima, an eight-square-mile volcanic island situated midway between American B-29 bases in the Marianas and their targets on the Japanese mainland, was one of the most bitterly contested of the Pacific War. Three airfields, an early warning radar station, and a strategic location made taking the island a necessity.

Prior to the land assault, the U.S. Army Air Forces bombed Iwo Jima for more than 70 days. Then naval forces shelled it for a further three days. Once ashore, Marine artillery fired half a million shells at Japanese positions, and throughout the battle Japanese defenders were subjected to continuous close air support from American carrier planes and further naval bombardment.

Nevertheless, the Japanese were so methodically entrenched inside Iwo Jima, in places five stories below ground, that once again as at Peleliu the vast majority of its hardened positions had to be taken at extremely close range by a handful of men at a time.

Over the 36 days of combat, the Marines lost 5,931 men KIA along with another 890 members of the Navy, mostly corpsmen, and more than 19,000 wounded. Only a few hundred of the Japanese garrison of between 21,000 and 22,000 survived. The battle marked the first time in the war that U.S. forces suffered more casualties than the Japanese. Japan’s new strategy had emphatically raised the cost in blood for the Americans.

Only 350 miles southeast of the Japanese home islands, Okinawa was the ideal staging point for the upcoming invasion of Japan. As on Peleliu and Iwo Jima, the Japanese employed the Defense in Depth to maximize American casualties. The battle was fought April 1-June 22, 1945, at times in torrential rain and knee-deep mud.

Likely the foremost example of horrific combat was a “pimple of a hill” known as Sugar Loaf, barely 50 yards wide and 300 yards long. The Marines were forced to assault its summit 11 times before they finally held it. In the process, 1,656 Marines died and another 7,429 were wounded over the 12 days it took to take the hill.

With terrible effect, Japan also used kamikazes in the greatest numbers yet during Okinawa’s 82 days of fighting. By the battle’s end, 2,000 planes, sometimes flying in waves of 200 to 300 at a time, caused more damage and inflicted more casualties upon the Allied armada than in any other battle of the Pacific War. Kamikazes sank 36 ships, damaged 368, killed nearly 5,000 sailors, and wounded a like amount.

When the battle for Okinawa concluded on June 22, more than 12,500 American servicemen were dead along with nearly 39,000 wounded and 33,000 non-combat casualties, mostly from “battle fatigue.” On the Japanese side, 95,000 men perished and as many as 10,000 surrendered. The battle also saw a heavy loss of civilian lives; estimates run from a low of 42,000 to as many as 150,000––one third of the island’s population.

In early April 1945, as the war with Germany reached its awful conclusion, the Soviet Union denounced its neutrality pact with the Japanese government. Signed four years earlier on April 13, 1941, the Russians told Japan they would not renew it. The Japanese should have taken the Soviet change of position for exactly what it was—an ominous confirmation that the U.S.S.R. would soon become an enemy of Japan.

Immediately following Roosevelt’s death in Warm Springs, Georgia, on April 12, Harry S. Truman succeeded him as president. After Truman took his oath of office, Secretary of War Henry Stimson told the new president that he needed to meet with him about a most urgent matter.

On April 24, Stimson and General Leslie Groves, in overall command of the Manhattan Project, briefed Truman for the first time about America’s top-secret atomic-bomb program. They told Truman they expected to have a bomb ready to test in a few months.

Three days after Germany’s surrender on May 8, Prime Minister Suzuki convened a meeting with The Big Six to discuss how Germany’s capitulation affected Japan’s wartime strategy. Foreign Minister Togo made his first attempt to move his government in the direction of ending the war after the members also received a dire report on Japan’s economy and war production.

Instead, Generals Anami and Umezu, along with Admiral Toyoda and Prime Minister Suzuki, asked Togo to convey Japan’s warmest regards to the Soviet Union, looking toward a friendlier relationship where it would be possible to purchase petroleum, aircraft, and other supplies it needed. Some members even suggested that it might still be possible to persuade the Soviets to join Japan in the war.

This perspective completely disregarded the reality that Russia had rescinded its Neutrality Pact with Japan a month earlier, had been an enemy off and on for 30 years before the war, and had been an ally of the British and Americans for over three years. Nevertheless, Togo attempted to carry out the Prime Minister’s request.

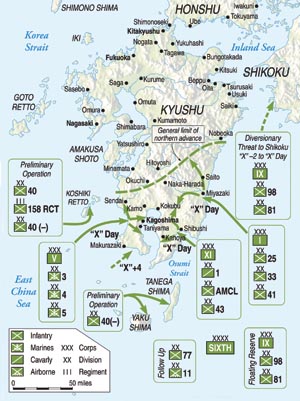

In Washington, on May 25, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) met and approved Operation Downfall, a two-phase plan for the invasion of the Japanese mainland. Phase I, code-named Operation Olympic, focused on the lower one third of Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese home islands.

The attack, scheduled to begin on November 1, 1945, included the following inventory: 766,700 men, 134,000 vehicles, 1.5 million tons of supplies, 22 fleet and 10 light aircraft carriers, and 2,794 aircraft. By itself, Olympic would have been substantially larger than the D-Day invasion of Normandy. The Chiefs expected 350,000 Japanese troops and no more than 2,500 aircraft to be defending Kyushu.

Phase II, Operation Coronet, targeted the Tokyo Plain. Slated to commence on March 1, 1946, it would have been even larger: 1,026,000 men (many in transit from the European Theater), 190,000 vehicles, 3,328 planes, and 2,640,000 tons of supplies. This amazing commitment of resources was about to be directed at an enemy whose merchant and naval fleets were already at the bottom of the ocean, whose air defenses were meager, and whose entire land area was blockaded by Allied warships.

In Tokyo on June 8, 1945, despite his country’s desperate situation, Emperor Hirohito acceded to the military’s call for all-out resistance through a heroic last stand by “100 million Japanese,” the majority of them civilians. Only two weeks later he decided to follow the recommendation of his closest adviser, Marquis Koichi Kido, and sent peace feelers to Moscow.

Ten days later the JCS briefed Truman on the plans to invade Japan. Prior to the meeting, Truman voiced his concern that the United States could end up fighting another Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other and asked the JCS to provide specific casualty estimates; a consistent answer was not forthcoming.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall sidestepped the question and gave an estimate of only 31,000 casualties, which was tied to only the first 30 days of combat and had come from MacArthur’s experience on Luzon in the Philippines.

Admiral William D. Leahy countered that he thought casualties could indeed be similar to Okinawa, where they amounted to 35 percent of the invasion force. Given the size of Olympic, it would mean 250,000 casualties with perhaps as many as one in four killed in action—or 60,000 more dead Americans.

Admiral Ernest J. King responded that the terrain on Kyushu offered more room to maneuver than on Okinawa. Therefore, casualties would be lighter. No one actually gave Truman a figure for the entire battle, although he had already heard former President Herbert Hoover’s estimate of 500,000 to a million dead (for both Olympic and Coronet)—an estimate that likely came from the “Smart Colonels” at the Pentagon.

Apart from the casualty discussion, General Marshall once again raised the idea of using gas against the Japanese, seeing it as no less humane than the flamethrowers or phosphorous already in widespread use, but he failed to gain agreement among any of the other attendees. The atomic bomb was not part of the plan, as it has not yet been tested. At the close of the meeting, Truman approved only Operation Olympic after he requested and got unanimous support for it.

In Tokyo in early July, Japanese military leaders finalized their plans for the defense of the home islands. The plan, called Ketsu-Go, involved as many as 28,000,000 civilians fighting with single-shot, muzzle-loading muskets, longbows, sharpened bamboo spears, and pitchforks acting as “cannon fodder” to draw fire away from Japanese soldiers. Women aged 17 to 40 and men from 15 to 60 comprised this civilian militia.

According to the 1944 census, the three prefectures over which the battle for the lower one third of Kyushu would have been fought contained a population of nearly four million people, a large percentage of whom would have been forced to participate in its defense.

The plan also included 2,000 conventional aircraft and more than 10,000 kamikaze planes flying directly off Kyushu to attack Allied troop ships and landing craft. Striking in waves so large that in three hours they would equal the 2,000 sorties the Japanese sent against Okinawa in three months, they expected to completely overwhelm the American invasion force.

In addition, the Japanese planned to employ 1,300 “special attack” (kamikaze) mini-subs and an unknown number of suicide divers with high-explosive charges strapped to their backs who would wait in the shallows along the beaches and swim out and attempt to sink landing craft.

Finally, rather than the 350,000 troops expected by the JCS for Operation Olympic, by August there were already 900,000 Japanese soldiers in Kyushu.

In the predawn hours of July 16, 1945, a $2 billion gamble by the United States government culminated in the successful detonation of the first atomic bomb at Trinity Site, Alamogordo, New Mexico. Scientists observed the explosion a mere 10,000 yards away from the blast, or between five and six miles. Truman, meeting with Stalin and Churchill at Potsdam, Germany, received word of the test later the same day.

The next day Stalin, Churchill, and Truman met to discuss Germany’s postwar fate and the continuing war with Japan. Truman was particularly interested in reaffirming Stalin’s commitment to join the war against Japan 90 days after Germany’s surrender, something the Soviet leader did in fact verify. A few days later Truman took Stalin aside during a break and mentioned “the bomb” without specifically calling it “atomic.” Stalin acted as though he did not understand but actually did; Russian spies had infiltrated the Manhattan Project, and Stalin knew the bomb was nuclear.

On July 21, American codebreakers intercepted an exchange of communications between the Japanese ambassador to the Soviet Union, Naotake Sato, and Foreign Minister Togo. In the cable Sato expressed the opinion that the best the Japanese could hope for in terms of a peace agreement with the Allies was to keep the emperor. Togo responded that The Big Six would never agree to that sole condition.

Four days later the Anglo-American Allies and China (the Soviet Union had not yet declared war on Japan) released the Potsdam Declaration demanding Japan’s acceptance of its terms or face “prompt and utter destruction.”

According to Commander George M. Elsey, duty officer of the White House Map Room from 1941 to 1946, the Potsdam Declaration definition of unconditional surrender was modified to: “We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces.”

The change from a blanket all-inclusive unconditional surrender to the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces was made because the United States. knew the Japanese, from decrypted messages, wanted to retain the emperor; the modification in language provided such a path. The same day Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb any time after August 1, weather permitting, as a visible target was required for its use.

By July 28, 1945, as General Marshall had predicted, even the most moderate of the Japanese leaders (Foreign Minister Togo) viewed the Potsdam Declaration as a weakening of American resolve and a basis for a negotiated peace rather than unconditional surrender.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, before Togo got a chance to begin discussions Prime Minister Suzuki quickly, at the insistence of General Anami, chose to “mokusatsu” the offer. (Roughly translated, it meant to “kill with silence.”) The decision sealed Japan’s fate.

On August 6, the B-29 Enola Gay dropped the Little Boy uranium atomic bomb on Hiroshima. After receiving the news, the Japanese leadership failed to meet for three more days because some members of The Big Six had more pressing matters to attend to.

General Marshall, who had been following the immense buildup of Japanese forces on Kyushu, began to seriously question the feasibility of Olympic. According to the latest American decrypts, Japanese troops on Kyushu now numbered 900,000 with nearly three months remaining before the invasion.

As a result, Marshall did two things. First, he cabled General MacArthur and asked if he thought the invasion should be moved to Hokkaido, the northernmost Japanese island. This would have been akin to moving the D-Day invasion from Normandy to Norway three months before its commencement.

Second, he considered the seemingly unthinkable; should the United States use as many as nine atomic bombs as tactical weapons in support of the invasion, over which American troops and Marines would then attack? Marshall had been following the scientific data coming out of Alamogordo after the Trinity test and believed American forces would be better off facing the risks of radiation than the vast numbers of Japanese defenders.

On August 9, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and attacked its Kwantung Army in Manchuria with well over a million men. With the bulk of its artillery, aircraft, and best troops long since stripped and sent to reinforce many of the islands previously mentioned in the Central Pacific, the Japanese were no match and the Russians rapidly gained the upper hand. The Soviets also struck, in much smaller numbers, the Japanese forces in Korea and in the Kurile Islands north of Hokkaido.

Later the same day, The Big Six finally met to discuss whether the war should be brought to an end or whether Japan should continue to resist. Suzuki, after requesting a vote, found the group deadlocked three to three.

On one side, Suzuki, Togo, and Yonai wanted to end the war with the sole condition of maintaining the emperor “with the understanding that the said declaration [of surrender] does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler” of Japan.

On the other side, Anami, Umezu, and Toyoda wanted to either fight the “decisive battle” on Japanese soil against the Americans or demand three more conditions in addition to the emperor—specifically Japanese control over war crimes trials, disarmament, and a guarantee of no Allied occupation force in Japan.

The men also discussed the recent atomic attack on Hiroshima. Admiral Toyoda told the group that no country in the world, not even the United States, could build more than one atomic bomb. Implied in his statement was a willingness to dismiss the loss of Hiroshima as a casualty of war since he assumed no further atomic attacks were possible.

About 1 pm, The Big Six, still meeting, got word of the second atomic bomb hitting the city of Nagasaki. The news stunned the men but failed to change any of their opinions. It did, however, elicit a menacing comment from Suzuki:“Maybe the Americans will simply stand off and continue to drop atomic bombs.”

[As a sidebar, it should be noted that the Japanese had two atomic bomb programs of their own during the war; both the Army and Navy each had projects. In fact, Prime Minister Tojo took a personal interest in the Japanese bomb project, believing that “the atomic bomb would spell the difference between life and death in this war.” Ironically, there was a consensus among Japan’s nuclear physicists that no county would be able to develop an atomic bomb during the course of the war.]

In an effort to break the stalemate among The Big Six and reach some decision, Togo and Suzuki, in a nearly unprecedented move, secured Emperor Hirohito’s agreement to provide his opinion to the group. The emperor told the cabinet he favored accepting the Potsdam Declaration with the single condition of keeping the Imperial Polity.

Anami, along with Umezu and Toyoda, only agreed to peace as long as the Allies accepted this condition. They also insisted on the conditional wording mentioned previously. If the Allies refused, Japan would continue to fight the war—this in spite of two atomic bombs and Soviet entry into the war against Japan.

The next day, August 10, news of the surrender offer with its single condition reached Washington. Truman immediately called a meeting to discuss whether the offer could be accepted as an unconditional surrender.

In the ensuing discussion, Undersecretaries of State Joseph Grew and Joseph Ballantine took issue with the language associated with the condition to keep the emperor, i.e., that the said declaration did not comprise any demand that prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler of Japan. They told the group that acceptance of the stipulation would allow the Japanese to continue with the same form of government that took them into aggressive war, and thus could potentially once again become a threat to peace, and that in the end they would have fought for almost four years accomplishing nothing.

Truman agreed and asked Grew and Ballantine to assist Secretary of State James Byrnes in drafting a counterproposal. The offer included two statements in direct response to the condition demanded by the Japanese, specifically, “From the moment of surrender the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers,” and “the ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.”

In no way did these declarations by the Allies not comprise a demand which prejudiced the prerogatives of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler of Japan. The statements ended the emperor’s authority.

Two days later, when the Allies’ counter-offer reached Japan, Anami immediately rejected it as it did not preserve the Imperial Polity. He flatly stated that Japan should either go back to fighting the war or demand all four conditions to end it. The Allied proposal sparked two more days of bickering among The Big Six that achieved nothing.

Worse yet, a group of junior Japanese officers plotted a clandestine coup to overthrow the Suzuki government should the peace initiative prove successful. Anami knew of the plot and neither supported nor quashed it.

Finally, on August 14, Togo and Suzuki again asked Hirohito to address the cabinet. The emperor told the group he wanted to accept the Allies’ counterproposal. Reluctantly, Anami, Umezu, and Toyoda all agreed. Additionally, Hirohito offered to record an imperial rescript to be broadcast to the Japanese people the following day telling them the war was over.

On the night of August 14-15, the conspirators launched their coup in an effort to derail the surrender. They seized the imperial grounds, essentially taking the emperor hostage, although they intended him no harm. They then attempted to gain the support of General Takeshi Mori, head of the Imperial Guards. Failing, they killed him and his aide, Colonel Michinori Shiraishi, and used Mori’s official stamp to forge a document that appeared to lend his support to the coup. Other members of the conspiracy went to the homes of Suzuki and Togo intent on assassinating both men; neither was home.

Next, the collaborators proceeded to the Household Ministry, determined to destroy the two copies of the imperial rescript stored there. Coincidentally, at the same time, the last American bombing mission of the war approached Tokyo. Fearing an atomic attack on the capital, officials blacked out the city. The soldiers tore the ministry building apart in the darkness looking for the rescripts but could not locate the hidden recordings.

The leaders of the coup d’état made one last attempt to get Anami’s backing, but he refused. He had given his word to the emperor and could not change it now.

In a final act of desperation, the conspirators attempted to gain control of a radio station with the objective of broadcasting a plea to the Japanese people to not accept the peace but failed to accomplish even this.

Shortly before 6 AM, Anami committed seppukuat his home, and one by one the principal members of the coup followed suit. Major Hatanaka used his pistol to put a bullet through the center of his forehead; Lt. Col. Jiro Shiizaki put a sword into his belly and then a bullet into his head, and Major Hidemasa Koga cut open his stomach.

Finally, at noon on August 15, Japanese radio broadcast the imperial rescript proclaiming the end of the war. In his speech to his people on that fateful day, Emperor Hirohito never used the word “surrender.”

Instead, he told his subjects that since the war had “developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage,” they would have to endure the unendurable for future generations and accept the Allied provisions to end the war. He added that Japan had not fought to aggrandize its territory, but rather to ensure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia.

The emperor did specifically mention the effects of the atomic bomb as a factor in reaching his decision, stating, “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable…. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Essentially, in an act of supreme benevolence, Hirohito said Japan would fall on its sword to save humanity from the Americans. Thus began the myth of Japan as victim in World War II and not an aggressor.

Within a few years of Truman’s fateful decision, debate began about whether the bombs were necessary. Were there other alternatives the president had that could have spared the Japanese from atomic annihilation?

What we know is that, in spite of the overwhelming losses in the last year of fighting, the destruction of two cities by atomic bombs, and the Soviet Union’s entry in the war against Japan, three members of Big Six—Anami, Umezu, and Toyoda—still wanted to either fight the decisive battle on Japanese soil or require four conditions for ending the war, and they showed absolutely no willingness to end the deadlock eight days after the attack on Hiroshima, until Emperor Hirohito intervened a second time.

Absent that act, their stance would have meant the war would have gone on and likewise at a minimum so would have the American campaign of blockade and bombardment.

As such, for however long it took to finally secure Japan’s surrender, the entire Pacific Theater would have remained at war. In Japan this would have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands—or possibly millions—from disease, starvation, exposure, and the ongoing air and sea attacks.

In the territories still occupied by Japanese military forces, Japan’s so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere—Manchuria, parts of China, Korea, Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Vietnam, Thailand, and New Guinea—people died at a rate of between 100,000 to 200,000 per month throughout the entirety of the war. Allied civilian and military POWs in these areas would most certainly have been at grave risk.

Lastly, the Allied forces necessary to sustain the blockade and bombardment lost, on average, 7,000 men killed per month. Consequently, any delay in bringing a termination to the war would have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

So what options did Truman have to the bomb in August 1945? There were three: he could have continued to blockade and bombard, resulting in the losses just mentioned; he could have gone ahead with the invasion, likely incurring hundreds of thousands and possibly millions of Allied casualties and killing millions of Japanese soldiers and civilians; or he could have allowed the Soviets to play a much greater role on the assumption he was willing to allow the war to continue significantly beyond its historic end on September 2, 1945.

The last option seems unlikely to have brought a rapid end to the war since, to seriously threaten the Japanese home islands, the Russians would have needed massive naval forces to carry out a large-scale invasion over water, specifically across the Sea of Japan or the Strait of Tartary, the latter 41/2miles wide at its narrowest point. The Red Army had become the most powerful land army of the war, but it had next to no ability to conduct amphibious operations beyond river crossings.

In the end, given Truman’s dual objectives of unconditional surrender and a desire to finish the war as quickly as possible while at the same time minimizing the loss of life, the atomic bomb offered the best chance of success and, in fact, accomplished both of those aims.

Once we had the atomic bomb, there was no option but to use it. In the end, using these bombs saved millions of lives, Japanese, American, and others. Rest assured if Japan had developed an atomic weapon they would have had no compunction about using it anywhere they could.

MacArthur wanted to use those 9 atomic bombs that Marshall thought about using against the Japanese, and bomb the Chinese at the Yalu River during the Korean War. Truman fired MacArthur and forced him into retirement.

You can read about MacArthur’s Korean plan here:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/douglas-macarthur-atomic-bombs-will-win-the-korean-war/

For many since the war, the question was less a matter of using the bombs than the choice of targets. Hiroshima did have a military base though not a very significant one. Nagasaki was a purely civilian city and had the largest concentration of Christians in the country. They were loyal to the government but not enthusiastic about the war. The actions by the Japanese in the occupied countries probably had a lot to do with the attitudes of the firebombing of largely civilian targets and the nature of the surrender terms presented to the Japanese. Probably the greatest effect of the bombing was to serve an object lesson in future military campaigns that this was one weapon that required a lot of thought before putting it to use. So far, so good.

This article ignores the threat to Japan of a Soviet invasion of the home islands and a possible result of shared occupation between the US and USSR. Certainly, the Zaibatsu leaders dreaded the Soviets. The “peace” group in the Japanese government recognized the Soviet threat and wanted to end the war before the Soviets went any further than Manchuria and the Kuriles.