By Flint Whitlock

Since the days of ancient Babylon, artists have taken the time to record their visions of war. Long before the invention of photography, scenes of battle were being sketched, painted, and sculpted by talented individuals able to imbue their creations with sentiments of glory, dignity, and heroism. The march of an army, the death of a general, and the charge of a brigade could all be captured for the enlightenment and education of generations to come.

Not until Spanish artist Francisco de Goya came along in the mid-1700s and recorded scenes of death, destruction, and human misery did war art dare to deal with the seamy and squalid side of combat. Matthew Brady’s photographs completed changing people’s perspective of war as intrinsically glorious and made them understand that war is a terrible enterprise that must be avoided whenever possible. Thanks to Brady (and other Civil War photographers) people could view actual images of real carnage that sickened and revolted them—headless corpses, bodies burned beyond recognition, hideous skeletal remains exhumed from shallow battlefield graves.

Although the wars that have taken place since the mid-19th century have been recorded primarily on film—moving and still—as well as video, it would be easy to conclude, therefore, that a soldier or sailor or marine armed with pencil, pen, and watercolor brushes is nothing more than a quaint anachronism.

But such a conclusion would be wrong. Even today, at the start of the 21st century, the combat artist is alive and well. Artistically talented individuals in uniform continue to sketch away, recording the mundane and the momentous, adding a personal, mind’s-eye touch to a scene that might otherwise be recorded only by the impersonal eye of the camera—or, given the limitations of photography, scenes beyond the ability of the camera.

World War II saw combat artists from all sides recording their impressions of the conflict. Sometimes the scenes they drew and painted captured the visual beauty—a lushly foliated tropical shore, a flight of aircraft silhouetted by a setting sun, a stark and stunning mountain vista. At other times the artists concentrated on capturing human faces—the grizzled, unshaven face of a soldier who had seen too much combat; the small, frightened face of a refugee child; the face of a pretty girl who reminded the boys of their girls back home. The tragedy and suffering of war—bombed-out villages, long lines of pitiful civilians, piles of dead in a concentration camp—also filled sketchbooks by the dozen. Whatever the subject, the artist was there to get it down on paper or canvas, to selectively leave in or omit certain details to convey his impression of the scene.

During World War II the Germans had an extensive kriegsmaler, or war painter, program, stemming quite possibly from the fact that Adolf Hitler considered himself an accomplished artist and was keenly interested in the arts, especially if they glorified the militarism of the Third Reich.

Each major German army, naval, or air force headquarters had attached to it a Propaganda Kompanie (PK) composed of writers, photographers, and artists whose twofold job was not only to capture the images of war but to boost morale on the home front.

Britain, Russia, Australia, Italy, Japan, and other combatant nations also had war artist programs. While many of the drawings and paintings produced were primarily for reproduction in newspapers and magazines, a large number of works also found their way onto museum walls.

The United States, too, employed a number of war artists. The first was probably New York muralist Griffith Bailey Coale. In the spring of 1941, he volunteered to become a Naval Reserve officer and “make paintings from sketches and drawings ashore and afloat of ships, docks, and all the intricacies incorporated in the running of a mighty navy.”

He got his wish—and perhaps more than he bargained for. On October 31, 1941, while sailing with a convoy to Iceland, Coale witnessed the German submarine attack on, and sinking of, the destroyer USS Reuben James, the first American warship lost to enemy action in the Atlantic; his paintings of the scene were reproduced in several magazines. The Navy’s Office of Public Relations, recognizing the value of having artists reflect the activities of that branch of service, instituted a program to attract those willing to risk their lives for art’s (and history’s) sake.

Captain Leland P. Lovette, the Navy’s director of public relations, expressed the purpose behind the program: “Painters could catch the dramatic intensity of a scene and put it down on canvas. They could also omit the confidential technical details a camera might reveal, thus making many interesting subjects unavailable for publication. Subjects beyond the range of photography can be vividly depicted by painters, such as action at night, or in foul weather, or action widely scattered over the sea or in the air.”

The Marine Corps, too, employed artists on the front lines. Brig. Gen. Robert L. Dening, public relations director for the Corps, said, “A special case for art in time of war may be made, for it is then that a man’s spiritual, as well as physical, being is most severely in need of sustaining strength.”

Marine Corps artists were first and foremost warriors. They were expected to hit a hot landing beach, wade in with the troops, and trade fire with the enemy. Then and only then would they make sketches, later finishing the work in the safety of a rear area.

In January 1943, a War Department Art Advisory Committee was formed and 42 Army artists—many of whom were already well- known painters and commercial illustrators—were selected to work in combat areas around the world. George Biddle, the head of the committee gave them their marching orders:

“Any subject is in order, if as artists you feel that it is part of War; battle scenes and the front line battle landscapes; the dying and the dead; prisoners of war; field hospitals and base hospitals; wrecked habitations and bombing scenes; character sketches of our own troops, of prisoners, of the natives of the countries you visit … the tactical implements of war; embarkation and debarkation scenes; the nobility, courage, cowardice, cruelty, boredom of war; all this should form part of a well-rounded picture. Try to omit nothing; duplicate to your heart’s content. Express, if you can, realistically or symbolically, the essence and spirit of war. You may be guided by Blake’s mysticism, by Goya’s cynicism and savagery, by Delacroix’s romanticism, by Daumier’s humanity and tenderness; or better still follow your own inevitable star. We believe that our Army Command is giving you an opportunity to bring back a record of great value to our country.”

Curiously, the only subject that Biddle advised the artists to stay away from was “official portraits.”

In the middle of 1943, however, the Army’s combat artist program came under fire from a suddenly budget-conscious Congress. From a war budget of nearly $72 billion, the Army combat art project’s miniscule $125,000 budget was cut. LIFE magazine picked up the contracts of many of the civilian artists, while a few generals assigned some of the enlisted artists within their commands to continue their work with individual units. In 1944, Congress reversed course and reinstated the Army’s combat artist program.

Not all the combat artists served in an official capacity. Within every infantry or tank company, artillery battery, Air Corps squadron, or naval vessel there were bound to be three or four men with artistic talent and even some with special art training or a professional art background.

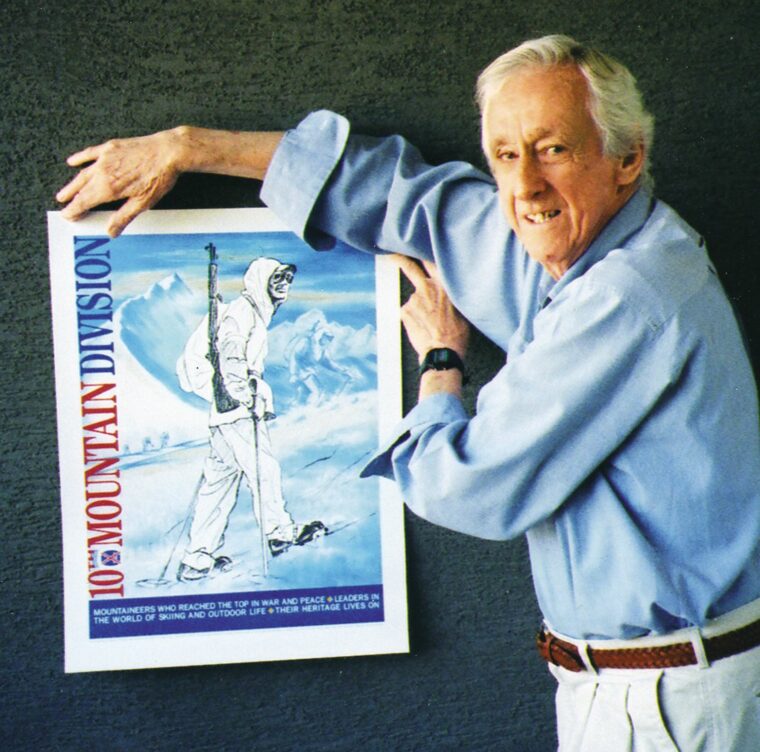

One such soldier within the 10th Mountain Division, the last American infantry division to be deployed for combat in Europe, was Jacques Parker, assigned to Company C, 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment.

Born in France to a French mother and an American father attached to the U.S. Consulate, Jacques attended L’Ecole St. Cyr Militaire, an elementary school run by Jesuits in Nevers, where rudimentary military training was part of the school day.

In the late 1920s the family moved to East Orange, New Jersey. Gifted both athletically and artistically, the lithe and nimble Parker loved sports—basketball, gymnastics, track and field, and, especially, cross-country skiing.

Parker showed his artistic abilities at an early age, making drawings of the subjects around him or imaginary scenes from his head. He even received his first pair of skis in exchange for a mural he painted on the wall of a local sporting goods store. After graduating from high school, he attended the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts with the dream of one day becoming a famous illustrator on the order of Norman Rockwell.

World War II, however, intruded upon Parker’s plans, as it did to so many others. He had been at the Newark School for only two and a half years when Germany invaded Poland and France and Britain declared war on the Nazi state.

Parker’s first thought was to somehow get into the war. “Back in 1940 and 1941, when England was alone against Hitler,” he says, “I so admired the handful of guys who were flying Spitfires around the clock and holding off the German Luftwaffe. At that age, being rather romantic, I wanted to join the Eagle Squadron [volunteer American aviators flying for the Royal Air Force], so I went up to Canada to enlist.

“I went to a recruiting office and there were two RAF officers sitting there—both of them had seen combat. One had a very crisp British accent. They asked me why I wanted to join the RAF and I did my best to answer their questions. The problem was, as they explained it to me, Americans in the Eagle Squadron were getting killed and, as the U.S. was getting closer to being involved in the war, there was a dispute between the Canadian and British governments—did an American citizen have to temporarily relinquish his American citizenship in order to enlist? Who would be responsible if you got killed?

“The officer got out from behind the desk, put his hand on my shoulder, and said, ‘Go home, son.’ I said, ‘Yes, sir,’ and, with my tail between my legs, I left.”

With his dreams of aerial combat dashed, Parker returned home downhearted but not discouraged. He next applied to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at King’s Point, Long Island, but was again rejected, this time for being underweight. His spirits suddenly picked up when, shortly after Pearl Harbor was attacked and the United States was thrust into the war, he learned that a special unit of skiers and mountaineers was being formed.

When the unit that would eventually become the 10th Mountain Division was organized in late 1941, Parker eagerly sought to be part of the “ski troops.” The division was unique; it was the only military unit that used a civilian agency (the National Ski Patrol System) as its official recruiter, and counted hundreds of foreign-born, world-class skiers, and ski instructors—from Norway, Switzerland, and Austria—in its ranks.

Getting into the 10th was not easy. For one thing, a volunteer had to have three letters of recommendation attesting to his character. For another, an applicant had to demonstrate his proficiency at either skiing or mountaineering or some other specialized skill required by the mountain troops.

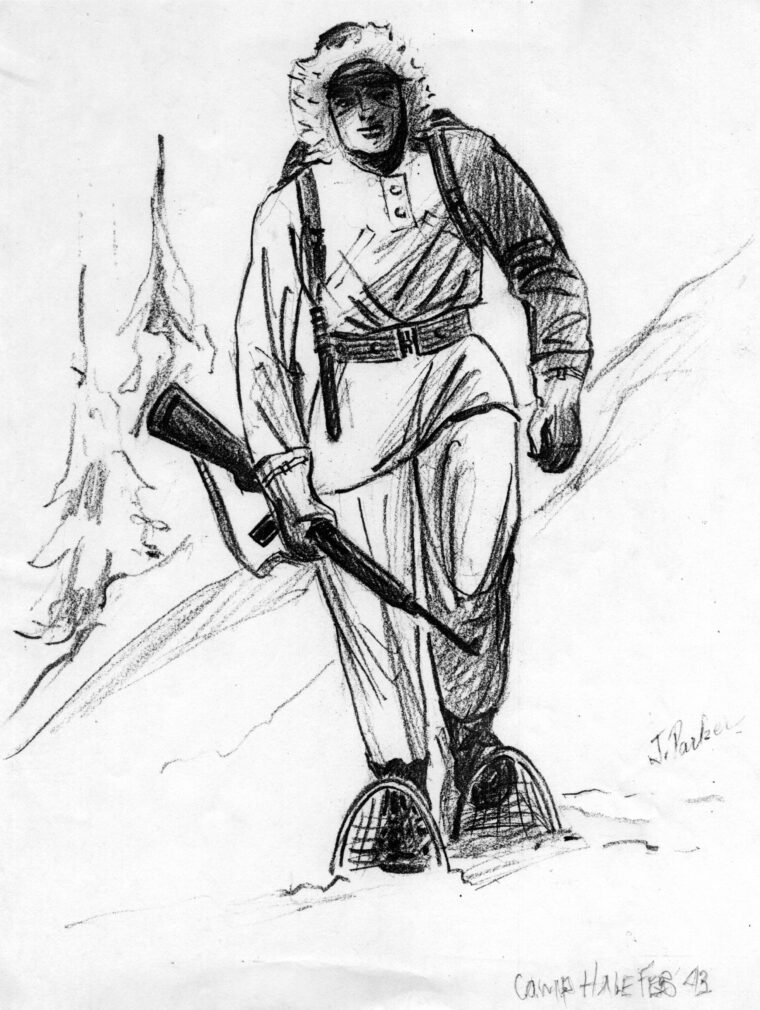

Fortunately, Jacques Parker was an accomplished cross-country skier, and obtaining the letters of recommendation was no problem. After a few weeks of training at Fort Dix at the end of 1942, he was sent by train to Pando, Colorado, near Leadville, site of the newly built Camp Hale and home to the 10th Light Division, Alpine, Pack.

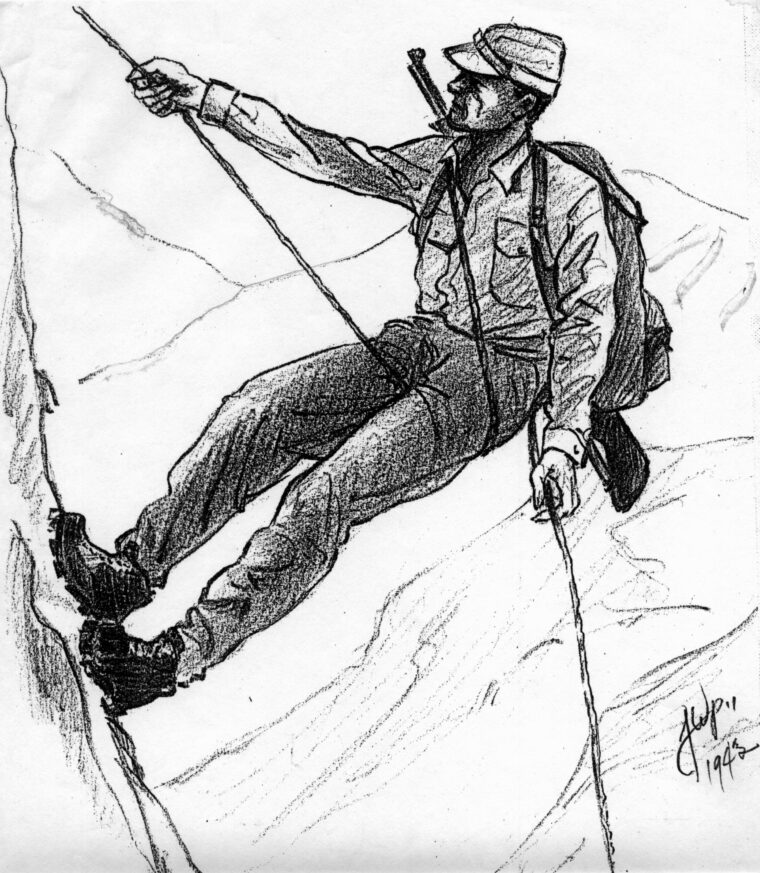

“When I got out to Camp Hale, Colorado,” Parker said, “I was 17 or 18 years old. I was taught the ‘Arlberg technique’ that Hannes Schneider, the great ski instructor, had brought over from his native Austria. Another Austrian by the name of Schaeffer was my instructor. He was an older chap with a heavy accent. I later became a ski instructor with the division, and also taught rock climbing.”

An inveterate sketcher, Parker drew everything that caught his eye—on anything that would hold a pencil line. “There were no art supplies at Camp Hale,” he said, so he used stationery or pads of paper he bummed from supply sergeants and other soldiers.

Parker made friends with Frank Kappler, Dartmouth class of 1936, who was the editor of the division’s biweekly newspaper, the Ski-zette. Kappler had a few former newspaper journalists and photographers on his staff but needed someone who could draw. With a number of excellent artists in camp from which to choose, Kappler selected Parker. “He was meticulous,” says Kappler, who would become a reporter for LIFE magazine after the war.

From the spring of 1942 until the summer of 1944, the 10th trained at Camp Hale, becoming what some have called “the most overtrained American infantry division of the war.” The men ached to see combat, and Parker hoped he would have the chance to draw something more than scenes of training and barracks life.

In June 1944, the division, not knowing if it were just a failed experiment and would be broken up to provide replacements for units with heavy combat losses, received a new commanding general. George P. Hays had received the Medal of Honor in World War I and had just served as the commander of the 2nd Infantry Division’s artillery in France. Hays brought a renewed fighting spirit to the burned-out, overtrained 10th and assured them that they would soon be seeing combat.

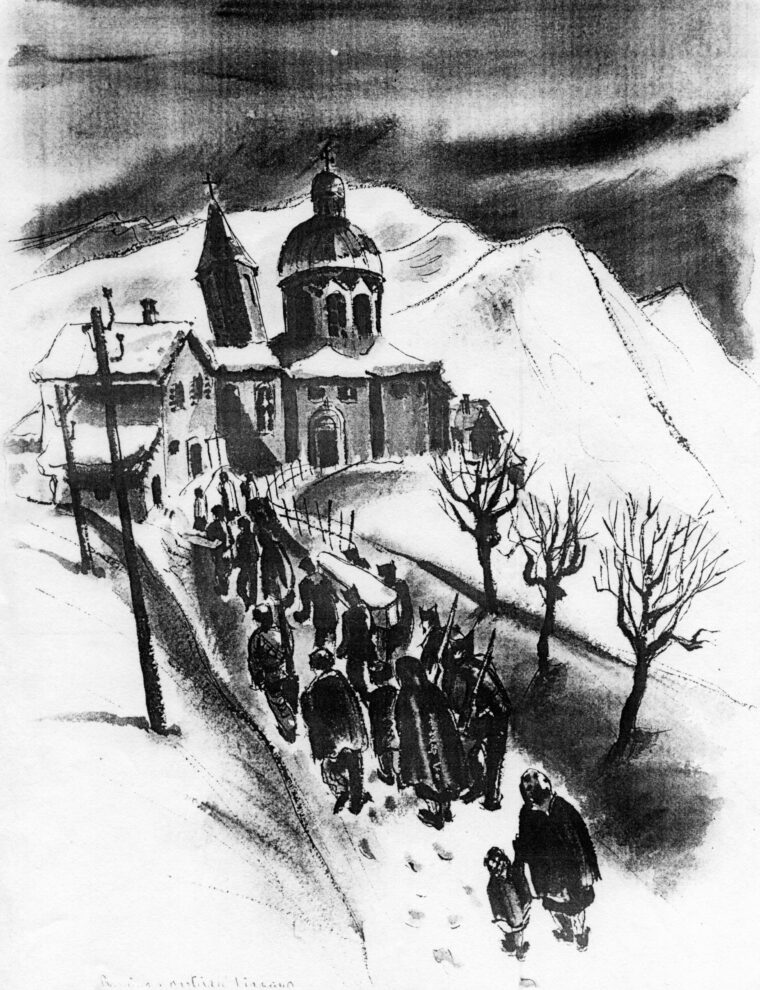

After training at Camp Swift, Texas, for six months, the outfit was redesignated the 10th Mountain Division and shipped to the one location where mountain fighting was still taking place—Italy. At the end of 1944, the division arrived in the port of Naples and was taken by train to the snowy, craggy peaks of the Northern Apennines, north of Florence.

Here Lucien Truscott’s Fifth Army drive had stalled in the autumn of 1944, and the Allies had been unable to punch through the Germans’ alpine redoubt and into the vital Po River Valley just to the north. Although the 10th was highly trained in mountain and winter warfare, no one was expecting the combat-inexperienced division to be able to do much better than the other combat-hardened outfits that had already been turned back by the enemy and the elements. The 10th determined that the key to seizing the mountain range was first seizing a five-mile-long series of connected peaks—an area known as Riva Ridge.

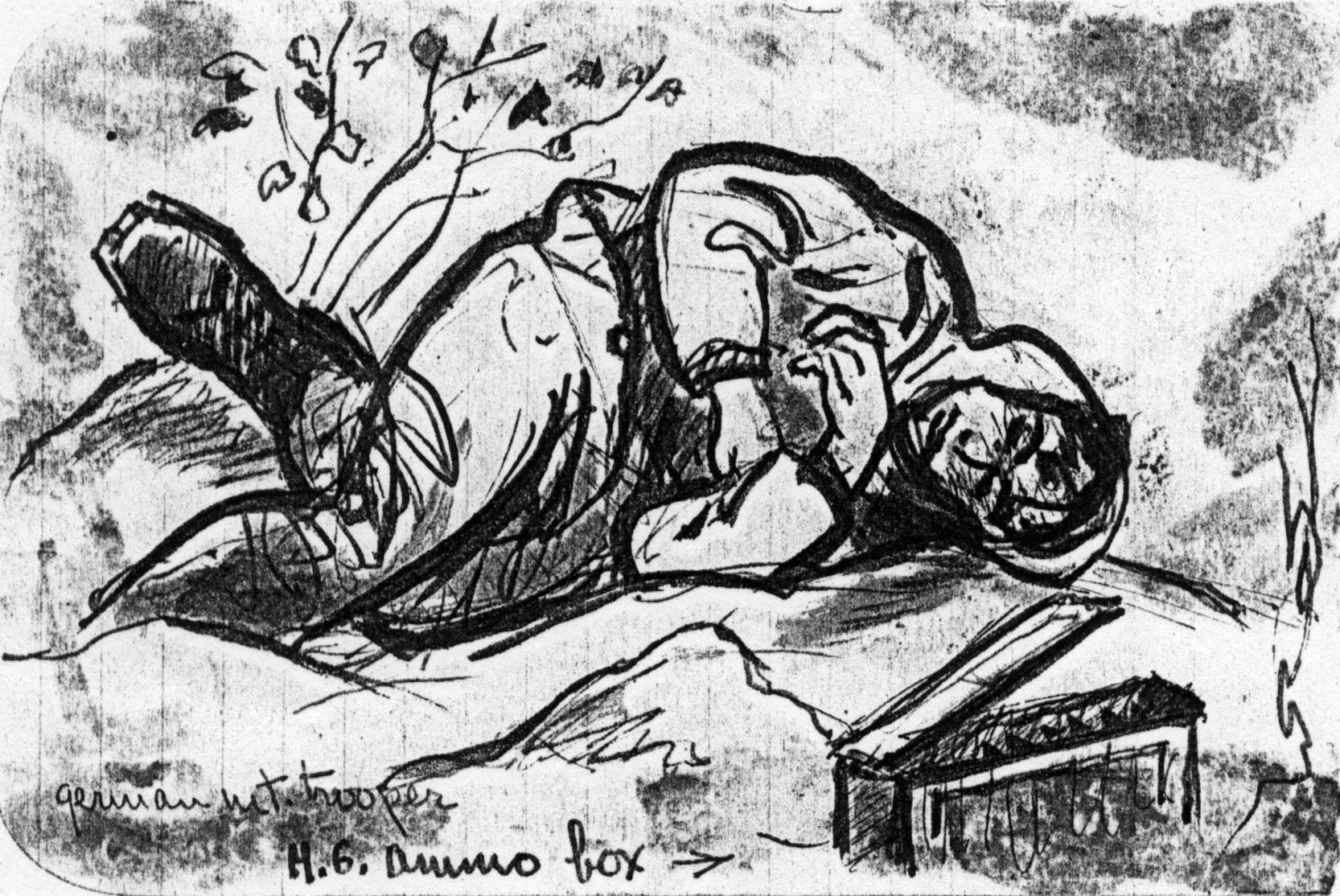

Riva Ridge, a commanding terrain feature that overlooked the all-important Highway 64, was occupied by a battalion of Gebirgsjäger (mountain troops). From their lofty perch, the Germans could call down devastating artillery fire any time they saw hostile movement toward the highway, the ridge, or the neighboring mountains.

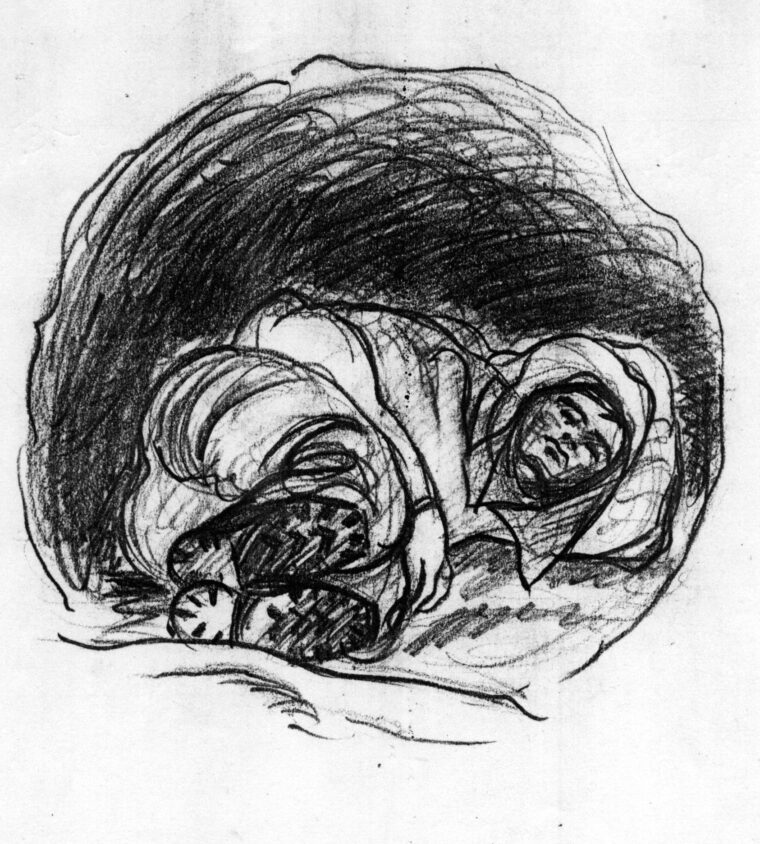

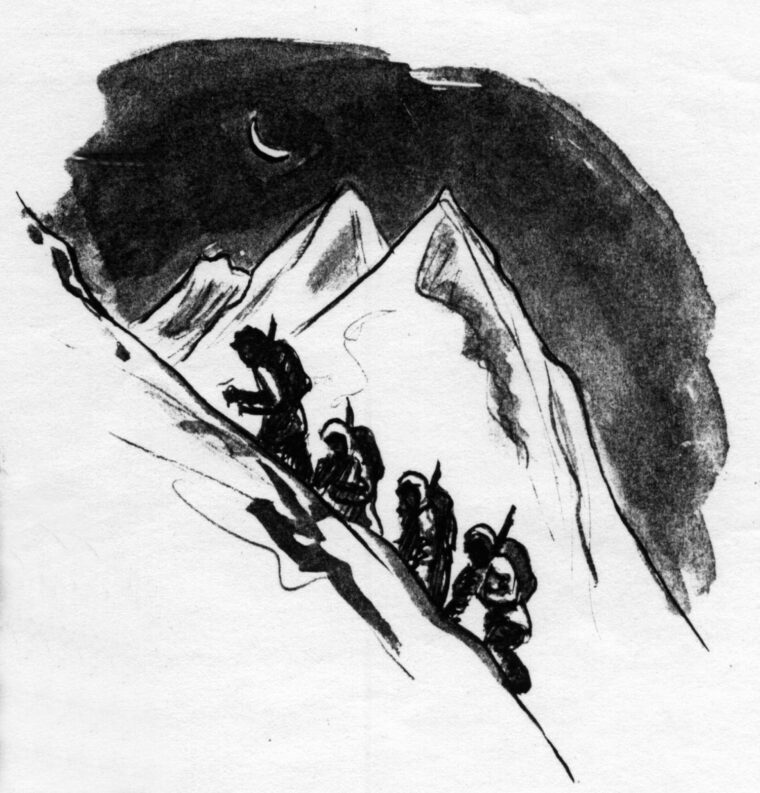

As a sergeant in charge of a .30-caliber machine-gun squad, Parker took part in the famous February 19, 1945, night climb up the nearly sheer face of Riva Ridge—the 10th’s first major combat action.

“We climbed all night, trying to be as quiet as could be,” says Parker. “Lieutenant John McCown was in the lead of our four-man section, and I took up the rear. As we reached the top, I joined Lieutenant McCown and peered over. Nobody there. We saw this small hut with a little chimney. Lieutenant McCown looked at me and then looked at the chimney. I nodded and reached for a grenade, but I thought no—it’s his baby. So he took one of his grenades and dropped it down the chimney and there was a huge boom because the blast was contained. It blew the door off the hut.

“I then went back down the ridge to bring up the rest of the company that was hiding in the woods down below—3,000 feet down below. That was probably the scariest part of my whole time in Italy. I slid, I scrambled, I tried to be as crafty as could be. We had prearranged a sort of bird call. When I got to the edge of the woods, I tried it. No answer. There was nobody there. It was eerie. I thought I might get shot by our own men. Then somebody returned the call, grabbed me, and pulled me into the woods. I was lying there, half laughing in a delirious way. With the company together, we went back up the ridge.”

The 86th Regiment took the ridge away from the Germans. Since no photographers accompanied the 1,000-man assault, Parker’s drawings are the only visual record of the event.

After Riva Ridge was secured, the rest of the division was able to assault a number of nearby, enemy-held mountains—a combat action that took nearly a week of bloody fighting and resulted in considerable losses to both friend and foe.

To maintain some degree of calm, Parker continued to draw and paint between battles. He carried a small watercolor tablet he had picked up somewhere, along with a pen, a brush, and a bottle of India ink. “I would either use spit or melted snow to wet the black tablet,” Parker recalls. “Sometimes I would have five or 10 minutes of quiet when I could draw something.”

At one point, a fellow soldier “liberated” a sketchbook from an Italian town and gave it to Parker. “I still have that sketchbook today,” the artist says.

Knowing that Frank Kappler always liked his work, Parker sent some of his best sketches back to Kappler, still editing the division paper, now called the Blizzard, at division headquarters. Parker carried his drawings in his mountain rucksack, but once while under enemy fire he had to abandon his rucksack and lost about a third of his artwork. To protect the drawings, he rolled them up and sent them back to Kappler inside empty mortar tubes.

Although he had photos taken by the division photographer, Roy Bingham, Kappler loved Parker’s artwork “It was beautiful stuff, because Jacques was in the line. He was a gunner!” says Kappler.

In March 1945, while the 10th was still battering its way through the mountains and spearheading the Fifth Army drive toward the Po Valley, Parker was medically evacuated.

“Why I wasn’t wounded I’ll never know,” he says. “We had been going for quite a while with whatever rations we had. I had become, without even realizing it, in bad shape, nutritionally. I remember wandering around with all my equipment on in some town or village when a medic came along. He asked me a few questions. I guess I was half-dazed. Nutritionally I was shot, but I had all this adrenaline like everybody in combat did—you’re operating on adrenaline and nerves. They put me in a truck and the next thing I know I’m in the 38th Evac Hospital in Florence.”

Parker couldn’t eat. “At the time, as a way of restoring your appetite, they would give you a little shot of whiskey. I slowly began to eat and regain my physical strength.”

In the cot next to Parker was a British flyer who had been wounded. “He had this wonderful moustache. I tried to grow a moustache to emulate him. Before we parted, he gave me a little container of moustache wax. The moustache lasted for a while, but I don’t think it was me.”

As he got stronger, Parker was transferred to the main U.S. military hospital in Livorno, on the west coast of Italy. Even in the hospital he continued to sketch the scenes around him.

“The Red Cross gave me paper and watercolors and brushes in the hospital,” he says. “I never stopped drawing and painting.”

During his recuperation, one of the doctors, a psychologist, came to him with an unusual request. “The doctor and I had gotten to be pretty good friends,” Parker says, “and he knew I was an artist. One day he said, ‘You’re perfectly all right, and it looks like the war’s going to be over any day now. Would you do me a favor while you’re here? We have a problem with a guy downstairs who was in the 34th Infantry Division who slogged it up from Southern Italy.”

The captain told Parker that the soldier was a lieutenant with a complex personality and a drinking problem. “He’s from Boston and was a very well-known comic-strip artist before the war. Would you go down there and talk with this man? We’ve had a hard time getting through to him.” Parker said he would.

The lieutenant was in a basement room with an iron-grille door. “This was where they put the ‘nut cases,’ in a sense,” Parker says. “You could hear the guys in the back who were really in bad shape.”

Parker paid several visits to the lieutenant, each time talking about art and earning more and more of his trust. “Every day he would relate a little more to me,” says Parker. “The captain told me that I helped open him up so the staff could help him. I remember that there was a column next to his bunk on which he had painted this beautiful trompe l’oeil ‘worm’ coming out of the shadows. I guess they had given him some paints and art supplies as part of his therapy. Art can be therapy.” After the war, Parker visited the ex-lieutenant, who was then living in New York’s Greenwich Village and working as an art director for a major life insurance company.

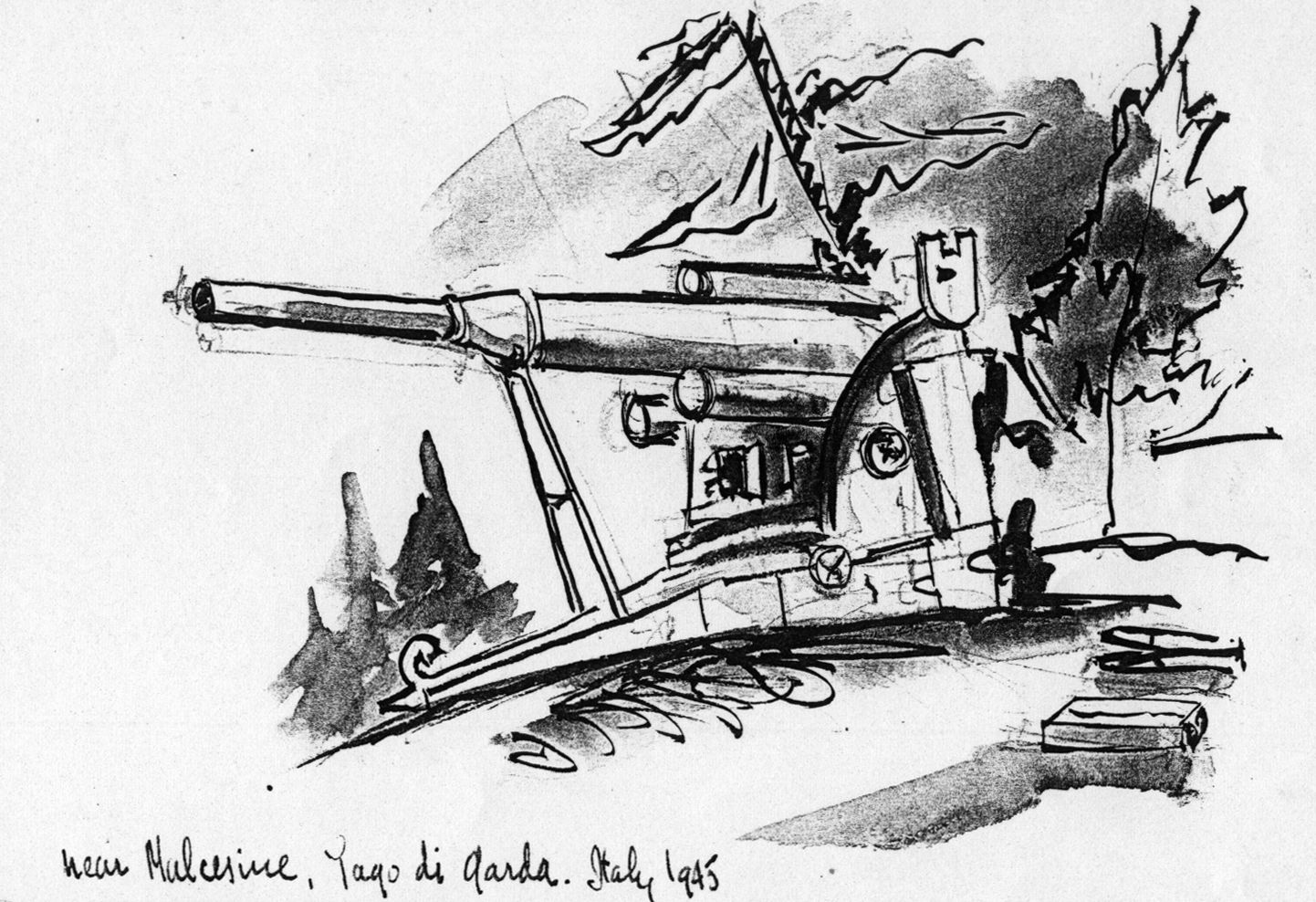

By the end of April 1945, the war in Italy was nearly over. The 10th Mountain Division had spearheaded the Fifth Army’s drive into the Po Valley, was first across the Po River, and had chased the retreating Germans all the way to Lake Garda, at the foot of the Alps.

“By then there was no purpose in my going back to the company,” says Parker, “so Frank Kappler went through channels and got me reassigned to the Blizzard staff.”

Besides working at Kappler’s side, Parker also made the acquaintance of Henry Moscow, who would go on to be the editor-in-chief of the New York World Telegram and Sun. “Henry Moscow was a gruff guy but he was one hell of an editor,” laughs Parker. “Once he took a pencil and lined through a guy’s story and said, ‘If you take out all those !*@#! adjectives, now you’ve got a story.’”

After the Germans surrendered, Kappler arranged for Parker to sketch the portrait of General Hays. “The general was wonderful to work with,” Parker remembers. “He was a very regular, straightforward, simple guy. I knew his time was limited, so I did everything I could to get the portrait right.”

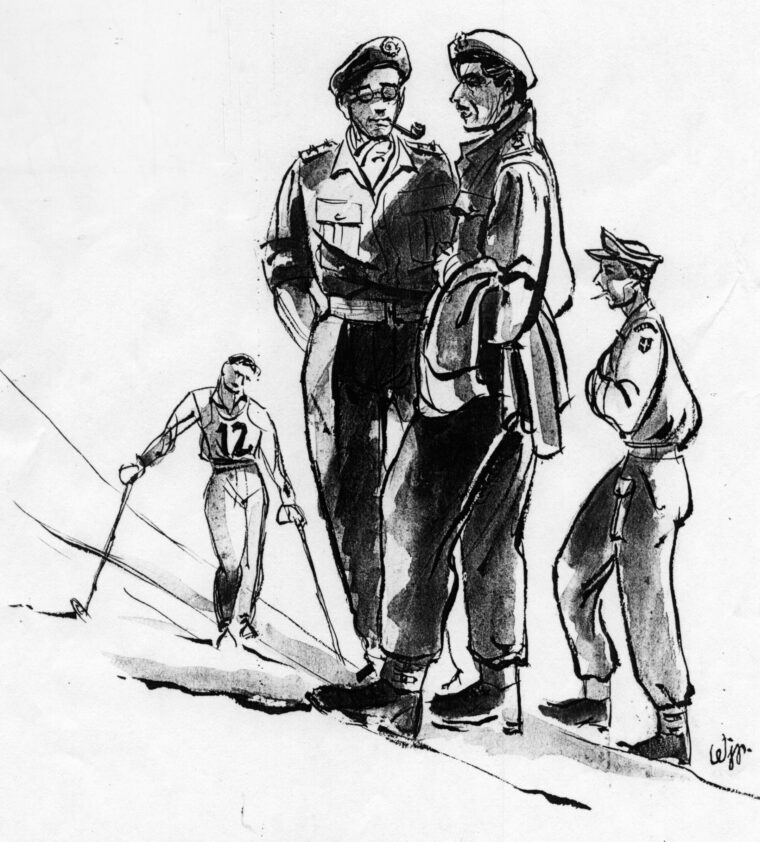

In the summer of 1945, the 10th held a ski race on Austria’s Gross Glockner mountain. “The Austrians there were our hosts,” Parker says. “We had guys like Steve Knowlton, who was an Olympic skier, and Walter Prager, the Dartmouth ski-team coach. An English team was also there. Fritz Kaiser, a photographer with the Blizzard, and I were assigned to go up there to cover the race. He took the photos and I did the drawings. That was my last assignment for the Blizzard.”

As a civilian after the war, Jacques Parker decided to pursue art as a full-time career and lead a “Bohemian” lifestyle. He found a loft in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, practically rubbing elbows with such famous painters as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, and dance maven Martha Graham.

Rather than live the financially precarious life of a painter, however, Parker opened his first commercial art studio and worked as a freelance illustrator for a number of advertising agencies. He also combined his artistic skills with his love of skiing and created over a dozen paintings of mountain and skiing scenes that became covers for Ski magazine in the late 1940s and early 1950s. For the next 50 years he worked for many of New York’s major advertising agencies and for such clients as Air France and IBM. The recipient of numerous awards, Parker also served as director of design for the City of New York under Mayor Ed Koch and taught at the Parsons School of Design. He also has had a few exhibitions of his fine art.

Still active as a designer, illustrator, and painter, Parker looks back on his time spent with the mountain troops with deep regard and appreciation. “The 10th gave so many of us a profound sense of brotherhood and accomplishment. It was another dimension to our lives.”

Flint Whitlock has written several books, including Soldiers On Skis, the story of the 10th Mountain Division in World War II, Rock of Anzio, a chronicle of the U.S. 45th Infantry Division, and The Fighting First, the experience of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division on D-Day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments