By David H. Lippman

Winston Churchill was against it. So was Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark in Italy. But the American chiefs of staff were for it, and so was General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in northwest Europe. The result was Operation Dragoon, one of the most controversial invasions of World War II, a stunning Allied victory that may have let the Soviet Union dominate Eastern Europe.

The original plans for the 1944 Allied invasion of Europe called for two massive invasions of France. The first, Operation Overlord, in Normandy, was the D-Day so familiar to the world. The second would be an “anvil” on which the Overlord “hammer” would resound, in the south of France, trapping the German war machine between the two massive invasions.

But as the Allies drove inland steadily from the Normandy bridgehead, Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, seeing victory as a mere matter of time, began to question the necessity of the southern France operation. He worried that the Soviets, driving hard from the east into Poland and Romania, would simply replace Nazi control of Eastern Europe with harsh Stalinism, replacing one tyranny with another. Churchill wanted to see the Allies pursue operations in Italy or use their naval superiority for landings in Yugoslavia in the Adriatic to drive toward Vienna, thus beating the Soviets into Eastern Europe.

Churchill was adamant about opposing this second invasion—even though he had agreed to it at the Tehran Conference in November 1943—telling Ike in August, shortly before the invasion began, “And if that series of events should come about, my dear general, I would have no choice but to go to His Majesty the King, and lay down the mantle of my high office.”

Eisenhower knew Churchillian rhetoric and bluster when he heard it, and he admired the British prime minister immensely. As Eisenhower’s public relations aide Harry Butcher wrote, “Ike said no, continued saying no all afternoon, and ended up saying no in every form of the English language at his command…. He was practically limp when the Prime Minister departed.” But politics aside, Ike had good military reasons to invade southern France.

Securing France’s Southern Flank

The biggest reason was an obvious one—supply. Eisenhower needed a major port to support his fast-moving legions, which were using up gasoline faster than it could be delivered to the front. With the destruction of the artificial “Mulberry” harbors by storms and the damage to the great port of Cherbourg by German demolition, Eisenhower did not have a port. Marseilles in the south of France would fill the bill nicely.

In addition, more than 100,000 German troops were holding southern France. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s drive along the Loire River was resulting in a long, poorly guarded right flank, open to attack by those troops. If all of France could be cleared of the enemy, Ike would be able to secure that flank. The best way to do this would be to join the Overlord and Anvil forces, as planned.

Furthermore, Ike wanted more troops on the border of Germany by winter—and that meant the drive from southern France had to kick in. In addition to the 36 Allied divisions breaking out of Normandy, Eisenhower needed those 10 divisions assigned to Anvil. Once the major southern French ports were open, an additional 40 U.S. divisions could be moved into the European Theater of Operations through them.

Another factor in Eisenhower’s mind was that half of the forces planned for the Anvil invasion were themselves French. So far France had played a limited role in her own liberation. Bringing French troops into play would empower that nation militarily and politically.

Eisenhower did not concern himself with the political issues that worried Churchill—that was the Combined Chiefs of Staff’s job. But they were becoming increasingly skeptical of Churchill, whose genius and rhetoric occasionally alternated with schemes that led to disaster, like the intervention in Greece in 1941 or the failed Anzio invasion in 1944. Churchill’s reversal on the southern France invasion seemed like another one of his madder ideas.

So the invasion of southern France went ahead, with the name changed from “Anvil” to “Dragoon,” for security reasons. Churchill himself yielded to the overwhelming American pressure, including the code-name change, saying he had been “dragooned” into the operation.

Defending Provence

The defense of Provence was the job of the German 19th Army under General Friederich Wiese. He in turn answered to General Johannes Blaskowitz, head of Army Group G. Wiese commanded 250,000 men in three corps scattered cross the Riviera’s beaches, described by historian William C. Breuer as a “land of pink oleander, grassy seaside terraces, garden walls, pastel villas, lush shrubbery, ornate estates, hyacinths, and white beaches.”

Wiese had three corps at his disposal divided into nearly seven divisions, three of them static coastal units long on emplaced artillery but short on transport. To make matters more difficult, many of his men were not Germans, but conscripted Russian and Polish POWs, who preferred a German Army uniform to starvation and would be unlikely to fight well. Some of them could not even be assigned to routine guard duty because few spoke German and fewer still could pronounce the passwords.

Wiese had only one panzer division at hand, the 11th, under Maj. Gen. Wend von Wietersheim, which was at half strength with 14,000 men, but only 26 PzKpfw. IV tanks and 49 PzKpfw. V Panthers at hand. However, the division was under Adolf Hitler’s control and could not be released from reserve without the Führer’s permission.

The Luftwaffe had 186 airplanes, and the Kriegsmarine could respond to invasion with 28 torpedo boats, nine submarines, five destroyers, and 15 patrol craft. Neither would be useful against the 300,000 men, 2,000 warplanes, and hundreds of ships that German intelligence estimated would hit southern France.

Wiese would depend heavily for defense on his 106 coastal artillery which ranged up to 340mm guns and could fire 700-pound shells more than 20 miles. He also relied on German engineering, which had turned holiday beaches into deathtraps with Teutonic efficiency: the sands were studded with blockhouses, anti-tank walls, tank traps, pillboxes, minefields, and decommissioned tank turrets mounted in concrete and villas camouflaged to conceal his heavy guns. He had 600 concrete pillboxes all told. But the overall picture was bleak. The best he could hope for was to inflict a bloody nose on the Franco-American invaders, then stage a careful withdrawal to the Reich through the Rhone Valley.

The Germans had one advantage. They knew the Allies were coming. Thanks to their own codebreaking efforts and spies on the ground in Italy, the Germans had a rough picture of the Allied invasion. It was too big to be kept secret anyway, and there was only one target—the Riviera and the Mediterranean ports.

The problem for the Germans was, as usual, Adolf Hitler. He ordered “no withdrawal” from southern France, his primary strategy since Stalingrad. Wiese’s men would have to stand and die on the Riviera’s beaches.

The First Phase: Commandos and Paratroopers

Meanwhile, the Allies prepared their invasion. They had the usual advantages: air supremacy to empower massive aerial reconnaissance, detailed information from the French Underground, decrypted German messages from their codebreakers, and, most unusually, a vast collection of photographs shot by prewar holiday-goers on the Riviera beaches.

Early in the war, the U.S. military had issued a call for citizens to provide such photographs, and now the request paid off. As historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “Thus, over the shoulders of a smiling couple in bathing suits taking the sun on the Ile de Porquerolles, one observes a pier suitable for tying up PT boats. The man who snapped Mademoiselle standing on the ramparts of an old fort inadvertently chose a background which helped an Intelligence officer to make a panoramic sketch of that part of the coast. A bather standing waist-deep in the waters of Baie de Bougnon tells us that an LST may beach there dry-ramp.”

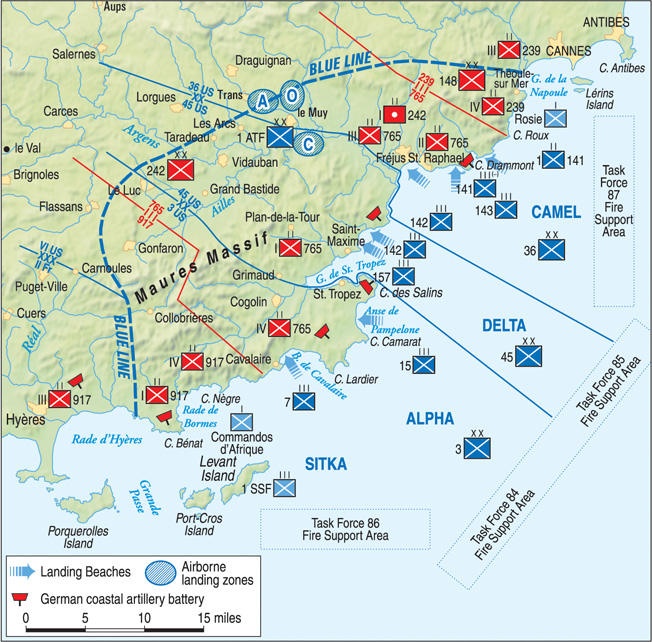

The Allied plan was not too complex. The target was a 45-mile stretch of the Cote d’Azur between Cavalaire sur-Mer and Agay, the targeted beaches being east of the German-held fortress of Toulon. Shortly after midnight on D-day, 2,000 Americans and Canadians of the elite 1st Special Service Force—the legendary “Black Devil Brigade”—would land on the Iles d’Hyeres, two pine-covered islands on the west flank of the assault beaches. Their target was a three-gun 164mm battery on the Ile du Levant, the easternmost island, which could inflict chaos on the assault. The Black Devils would silence this battery before the main force arrived on the Riviera.

Simultaneously, a detachment of French commandos, code-named Romeo, would attack the mainland just north of the Iles d’Hyeres to block the main coast road leading from Toulon to prevent German reserves from moving up on the beaches.

![Generaloberst von Blaskowitz, Chef einer Heeresgruppe im Westen, ¸berzeugt sich auf einer Besichtigungsreise von der Verteidigungsbereitschaft eines bestimmten K¸stenabschnitts. Hoch ¸ber einer Stadt gewinnt der Generaloberst einen Einblick in die Verteidigungsmˆglichkeiten. PK-Kriegsberichter Bronsema (Scherl) 27.6.44 [Herausgabedatum]](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/W-Op.-Anvil-feb13-11.jpg)

On the extreme right flank of the invasion area, another French naval demolition team was to land by rubber boats a short distance west of Cannes and establish similar blocking positions.

Next would come an airborne assault by the slapped together 1st Airborne Task Force, which consisted primarily of Britain’s 2nd Parachute Brigade, the American 517th Parachute Regiment, two more American parachute battalions, and an American glider battalion. This temporary outfit even included the antitank platoon of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the legendary Nisei outfit. The task force was to drop around Le Muy and capture the town, which stood at the center of a web of roads. Lt. Col. William P. Yarborough, commanding the Task Force’s 509th Parachute Battalion, told his men their job was to “raise as much merry hell behind enemy lines as the law allows.”

The task force consisted of a mix of green and veteran troops and had only a few weeks to mesh together. But it had one advantage, the boss was Maj. Gen. Robert T. Frederick, age 37, who had brilliantly led—mostly from the front—the Black Devils in Italy.

Landing the American Divisions

After the paratroopers dropped, the plan called for three American divisions to land. All were veteran divisions, coming under the VI Corps, led by gravel-voiced Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., a hard-driving cavalryman who was as tough on the battlefield as the polo ground.

Alpha Force, consisting of Maj. Gen. John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel’s 3rd Infantry Division, would storm two beaches 13 miles apart, at Cavalaire and Pampelonne. In the center, Delta Force would land Maj. Gen. William W. Eagles’s 45th Infantry Division at Baie de Bougnon and La Nartelle. On the right flank, Camel Force would deliver Maj. Gen. John E. Dahlquist’s experienced 36th Infantry Division onto the coast at Saint-Raphael. Once the three divisions had consolidated their beachhead, the 2nd French Corps, under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, would pass through the American beaches and drive on the ports of Toulon and Marseilles.

The whole force would come under the command of General Alexander “Sandy” Patch, commanding the U.S. Seventh Army. Patch was a soft-spoken and religious man who mixed easily with his fighting men, chatting with them while rolling a cigarette from a sack of Bull Durham. He had fought in World War I and led the Americal Division in battle against the Japanese on Guadalcanal, defeating a tough enemy. Patch had a lot of worries as he mounted the offensive. His only son, Captain Alexander M. Patch, Jr., was fighting with an infantry outfit in Normandy.

Once the French were ashore in force, they would be joined by the French I Corps, and De Lattre would move up to command the First French Army.

The French were eager to fight but annoyed that they would not have a major role in the initial landings. Patch mollified them by saying, “Don’t forget, it is you who will have the honor of seizing our two principal goals—Toulon and Marseilles!”

With the plan in hand, there was little left to do but mount up the assault. Landing day was to be August 15, 1944, and the convoys began steaming out of Italian, Corsican, and North African ports on August 10.

Within a day, the Germans knew the Allies were moving from Abwehr agents in Spain, air reconnaissance, and decrypted radio messages. “Large Allied convoys have left North African ports with troops and supplies. Destination unknown,” read the message to Army Group G. Wiese and Blaskowitz correctly assumed the Allies were headed for the Riviera. They asked Hitler for permission to bring up the 11th Panzer Division. No answer.

Meanwhile, the Allied invasion fleet was bearing down on the Riviera. Allied aircraft pounded the German installations and airbases in southern France, pinning down the defenders. The Allies had 5,000 aircraft deployed in the Mediterranean, 2,000 on Corsica and Sardinia alone.

The Allied armada was impressive, even by World War II’s gargantuan standards. A total of 880 ships, vessels, and beaching craft reached the assault area under their own steam, and 1,370 landing craft were carried in the various davits. The boss was Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, nephew of a New York City mayor Abram Hewitt, flying his flag in the headquarters ship Catoctin.

His force included three American battleships—the Texas, Nevada, and Arkansas—all veterans of Normandy, a British battleship, the Ramillies, and the French Lorraine. All were older dreadnoughts, no longer fast enough to keep up with the fast carrier task forces being used in the Pacific, but still packing 14-inch (12-inch for the Arkansas) guns that could bust through concrete blockhouses. Also in the task force were three heavy American cruisers, seven British escort carriers, two American escort carriers, and numerous American, British, and French light cruisers and destroyers.

The Allied nature of the invasion force was seen in its escorting armada. Among the ships present was Greece’s destroyer Themistocles, Canada’s transport Prince Henry, Australia’s escort carrier HMS Attacker commanded by Captain H.B. Farncomb, and New Zealand’s 24 Seafire fighter aircraft on HMS Stalker, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. G. Reece. Some of the ships were historic: USS Nevada had been beached during the attack on Pearl Harbor, HMS Ajax had cornered the German pocket battleship Graf Spee, HMS Ramillies had seen action for 28 years, gunboats HMS Aphis and HMS Scarab had served on the Yangtze River and been pulled out in advance of the Japanese attack on Shanghai in 1941.

“Resistance by All Available Means”

On the 13th, Hitler finally acted on Blaskowitz’s request and ordered “resistance by all available means” on the southern French coast. That meant 11th Panzer Division could limber up. Blaskowitz’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Heinz von Gyldenfeldt, barreled into his boss’s office, shouting, “Here’s the order! It just came through.” Moments later, Gyldenfeldt was on the phone to 19th Army, giving Wiese the good news.

That afternoon, the 11th Panzer Division was loaded onto 33 trains to head east the next day, but the unit was forced by Allied air attacks to abandon the trains and take to the roads. Armored cars in the lead, the division thundered for the Rhone with its “vehicles bristling with foliage, speeding along the main highways in broad daylight, leaving ample space between them, darting from one place of concealment to the next,” according to the division’s chief of staff.

That same day, the British destroyer HMS Kimberley steamed through the lines of Allied ships bearing a precious passenger: Winston Churchill himself, who swallowed his pride for the opportunity to watch an actual invasion in action. From the ship’s bridge, he flashed his V-sign while GIs on the transports alongside cheered him. Also present on the destroyer was Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson, and aboard the Catoctin was Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal.

Operation Dragoon got started at 10 pm, on August 14, when the heavy cruiser USS Augusta arrived off the Hyeres roadstead to supervise the raids on the western flank. Just after midnight, some 396 troop carriers roared off airfields from around Rome, carrying more than 5,000 paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Task Force to their destinations.

The planes also dropped 300 life-size dummies dressed as American paratroopers rigged with noisemaking equipment and explosive charges, which simulated the sound of battle when they hit the ground. The noise and pyrotechnics frightened defenders of the 244th Infantry. The diversionary effort was extremely successful, as German troops chased or ran from the dummies through the woods and valleys behind the invasion coast. Next day, Radio Berlin fumed that the fake paratrooper attack was something that “could only have been contrived by the lowest and most sinister type of Anglo-Saxon mind.”

The First Casualties of Operation Dragoon

The invasion of southern France began with Operation Romeo’s 800 French commandos, under Lt. Col. Georges-Regis Bouvet, going ashore at Cap Negre from 20 landing craft. Their job was to scale a 350-foot cliff and destroy German artillery. Leading the commandos in a rubber boat was Sergeant Georges du Bellocq, who climbed over barbed-wire obstacles and into a network of trenches he thought was empty. Then he heard a voice yell, “Ludwig! Ludwig!” Bellocq leaped up and opened fire. The enemy soldier screamed once, then “gurgled and shut up,” probably the first German to die in the invasion of southern France.

The gunfire set off a lively firefight—between German positions. “From that moment on during the whole rest of the night,” Bellocq recalled, “the Jerries hardly left off shooting at one another.”

At the same time, Sergeant Noel Texier, who had been told this would be his final combat mission, led his men ashore at Cap Negre and began climbing its 350-foot high cliff. The Germans above hurled grenades down at him, and Texier was killed—probably the first Allied soldier killed in Operation Dragoon.

Meanwhile, Bouvet, in his landing craft, waited for the green flares that would mean his advance party had reached the right beach. No sign of them. He decided to go in anyway. The Canadian midshipman commanding his Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) refused to go in. The determined Bouvet shoved a pistol in the Canadian’s ribs and ordered him to go ashore. The French commandos landed a mile west of their beach.

Undeterred, the Frenchmen climbed out of their landing craft. Before scaling the cliff, they marked the end of years of exile by scooping up handfuls of wet sand and pressing it to their lips.

Amid chirping crickets, the Frenchmen climbed the cliff, taking the Germans by surprise. They picked up Bellocq’s team and started destroying gun emplacements and setting up a roadblock on the coastal highway. Bouvet’s band killed 300 Germans, took 700 prisoners, and only lost 11 dead and 50 wounded.

Next up was Task Force Sitka, the 1st Special Service Force, under Colonel Edwin Walker. Their targets were the 164mm guns that could savage the invasion. French intelligence officers insisted the guns had been destroyed when the Germans took over the Toulon base in 1942, but the attack went in anyway.

The American-Canadian force, remembering they had not been fed before their previous assault landing in the Aleutians, demanded dinner before they went ashore. They got steaks.

The Black Devils Attack

The Black Devils disembarked from Prince Henry at 1:30 am and found little opposition. They did find what 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment commander Major Edward Thomas called “maquis brush, a head-high impenetrable growth,” which slowed down the advance. Soon it came under machine-gun and mortar fire. Sergeant Kenneth Betts recalled, “A mortar shell hit right directly in front of me, mushrooming out on both sides. If I had been anywhere else other than right where I was, I would have been dead. It didn’t knock me out, but it did make me foggy. It wiped out five guys on one side and five guys on the other side—I didn’t get a scratch. They said, ‘Betts got it this time!’ No, I didn’t. I walked out and someone yelled at me, ‘Holy Christ! There’s a corpse coming at me!’ they thought it wiped us all out. I heard, ‘I need a volunteer to take the wounded back,’ and I said, ‘I’ll volunteer, Mack,’ and he said, ‘I thought you might.’ I said I had had enough of this island already.”

The “braves,” as the First Special Servicemen were called, fought through the difficult terrain and found the three menacing guns, all deserted—no German troops. The Black Devils attacked and found the guns to be dummies—ordinary drain pipes skillfully deployed by the Germans to imitate heavy coastal guns. “Another dry run!” yelled a brave, and the Germans answered him with mortar fire. The German garrison of 200 men was holed up in a cave at the other end of the island with eight or 10 mortars, machine guns, and plenty of ammunition. The Black Devils moved in on the cave supported by shells from the British destroyer HMS Lookout.

As dawn broke over the Ile du Levant, the Black Devils had the cave surrounded on three sides. Bazooka men fired their missiles into the cave’s mouth, and the Germans put out white flags. The battle was over.

Colonel Walker signaled Admiral Lyal Davidson, “Islands utterly useless. Suggest immediate evacuation. Killed: none. Wounded: two. Prisoners: 240. Enemy batteries: Dummies.”

Davidson told Walker to stay put, and that turned out to be the right move: two Black Devils walking along a path later in the day came face to face with two German soldiers. Both sides were equally stunned to see each other and stared mutely for moments until both parties fled in opposite directions. Finding there was still resistance on the island, the Black Devils moved in to find 58 Germans holding out in a Napoleonic-era stone fort with 12-foot walls. The Black Devils called for naval gunfire, and the USS Augusta loosed her 8-inch shells at the fort, but her shells bounced harmlessly off the old fortress.

While this went on, the destroyer Somers spotted two strange ships on radar. They turned out to be a German auxiliary named Escabart and her escort, the corvette UJ-6081, which had been the former Italian corvette Camoscio, before the Germans seized her when Italy changed sides in the war.

Somers challenged them with a searchlight. They did not answer, so the destroyer opened fire and her first shot sent the Escabart bursting into flames. The corvette turned east at high speed with Somers in hot pursuit. The crew in Augusta’s combat information center watched the action on its radar screens with great interest. An ensign exclaimed, “Maybe it’s the Tirpitz!” The Germans, unaware of this compliment to their vessel, abandoned ship after daybreak, unable to escape. A boarding party from Somers found the corvette had taken 40 hits and could not be salvaged. They picked up her charts and left UJ-6081 to sink at 7:22 am on the 15th. But the flaming Escabart alerted every German on shore that something was up.

On the Catoctin, Patch worried about the Black Devils. He sent an aide to find out what was going on. “In that case, general,” said the visiting Forrestal, “I wouldn’t mind being in the party. It’ll give me a chance to stretch my legs.” Forrestal went ashore to help the aide. At 11 pm on August 15, the Germans holding the old fort, seeing themselves surrounded by Black Devils and Allied warships, surrendered.

At the opposite end of the assault area, film star turned U.S. Navy Lt. Cmdr. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., led Task Force Rosie, designed to block the coastal roads from Cannes to the invasion area. His operation consisted of the two British China Station gunboats, four fast PT boats, a fighter-director ship with sound equipment to broadcast a recording of naval gunfire, and 67 French commandos of Groupe Navale d’Assaut de Corse under Captain de Frigate Seriot.

Fairbanks’s little flotilla sailed within radar range of the French coastline, spewing out metallic chaff and playing its recordings as loudly as possible. The commandos went ashore and ran smack into a minefield. Unable to achieve their objectives, they tried to withdraw, only to be mistaken for Germans and shot up by prowling Allied aircraft. Only 40 of the Frenchmen survived, and they were captured by the Germans. Luckily for them, they were liberated the next day by the 36th Infantry Division.

Aphis and Scarab hurled four-inch shells at the Germans. Lt. Cmdr. John D. Bulkeley, commanding the destroyer Endicott, shepherded the PT boats onto the correct course. Two years before, Bulkeley had earned the Medal of Honor for carrying General Douglas MacArthur from Corregidor to safety. Once again, Bulkeley was in the thick of the action. British Vickers Wellington bombers dumped strips of chaff to confuse German radar operators.

The naval and sonic ruses de guerre worked well. Next day, Berlin Radio announced that the Germans had fended off a bombardment of Cap D’Antibes by “four or five battleships.”

The Germans were certainly puzzled. At his headquarters near Avignon, Wiese was awakened by 4 am to reports of landings and naval actions. “What do you think of it?” asked Wiese’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walther Botsch. “Where do you think the main attack will be?”

Wiese stared down at his map and said, “I don’t know, Botsch. I simply don’t know. We’ll have to wait and see what develops.”

Meanwhile, the parachute Operation Albatross was opening up. Le Muy was where Route Napoleon met National Highway Seven, and the paratroopers went in at 4:30 am.

Before climbing into his C-47 Dakota transport plane, Yarborough told his men, “Troopers, you have been chosen to spearhead the invasion that may break the Krauts’ back. You now know where we are going. We are going to hold there until hell freezes over or we are relieved, whichever comes first! In case anything happens, I want you to know how proud and glad I am to be with you. I’ll see you in France! God bless you all!”

Another source of support came from Archbishop Francis Spellman, on hand as apostolic vicar to the armed forces, to give his blessing and encourage the troops with a last-minute service attended by numerous non-Catholics. After returning to New York, Spellman wrote personal letters to the parents, wives, and next of kin of many of the men he blessed.

“We’re Looking For Krauts”

The parachute assault was spearheaded by pathfinders, who dropped with radar sets and T-lights. The British pathfinders got their radar beacons set up, but the Americans were less successful. But when the British paratroopers landed, Lieutenant T.W. Williams had a close call. He saw a shadowy silhouette nearby and prepared to shoot it. Then the silhouette called out, “Who are you?” in English. Williams called back, “Who are you?” and the silhouette answered, “I’m Brigadier Pritchard.” Williams lowered his gun and thus avoided killing the commander of 2nd Parachute Brigade.

The paratroopers’ aerial armada stretched 100 miles and brought in 5,607 paratroopers and more than 150 artillery pieces. But the planes headed for the 509th Parachute Battalion’s drop zone could not find it—the pathfinders had not set up their beacons, and the drop zone was covered with fog. The pilots dropped their paratroopers based on estimates of their flight position as suggested by the hilltops.

At 4:18 am, the red light went on in Captain Ernest “Bud” Siegel’s plane, and the former New York State Police officer leaped out, leading his men into the dark. Siegel’s parachute caught on a tall tree, leaving him swinging 15 feet off the ground. He cut the harness strands with his trench knife and scrambled down the tree.

That fate befell many of the 509th. Pfc. Leon Mims’s chute snagged on the top of a towering pine tree, and the 25-year-old Georgian was trapped, angling 40 feet in the air. A shell from a German gun exploded against the tree, shaking Mims loose and sending him tumbling down through the branches and to the ground. A buddy came up and gave Mims a shot of morphine. Mims told the paratrooper to leave him there. Mims would lie there, racked with pain, the morphine wearing off, for three days, until a Frenchman moved him by wheelbarrow to his house to await pickup.

Fortunately for all concerned, the paratroopers were dropped near their drop zones. Blue lights drew the men of the 509th together, and they set out on their way. A Frenchman invited his liberators to his house to celebrate with wine. “Hell, no,” snapped Yarborough. “We’re looking for Krauts.”

The 517th Parachute Regiment, dropping 10 minutes later, was more scattered by the fog. Lieutenant James A. Reith, a platoon leader in the 517th Infantry Regiment, found himself standing next to a mysterious figure staring up at the sky. The stranger smelled of fish. Reith remembered an intelligence briefing that said German troops smelled like fish from a salmon-heavy diet, and Reith did a double take on his companion. He was wearing a German helmet. Reith whipped out his .45 and shot the German in the stomach.

Soon scattered groups of the 517th were banding together and fighting like their buddies in Normandy two months before, for unfamiliar objectives against an unknown enemy. At least they had a shorter wait for daylight. But it was difficult. Someone asked the 517th’s commander, Colonel Rupert D. Graves, “Where are we?”

Graves answered, “I feel reasonably certain that we’re somewhere in France. Other than that, I haven’t the faintest notion where we are.” He led two privates.

Others landed far from their objectives. Lt. Col. Melvin Zais, a future four-star general, landed 25 miles from his objective. He assembled 105 paratroopers, and they headed off to their drop zone in the gathering dawn, in approach-march formation. As they hiked through the countryside, a flight of Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter bombers swooped down on them. The Americans took cover from the bombs. Finally, a paratrooper was able to put out a yellow smoke pot, the recognition signal, and the P-38s zoomed upward.

Zais was not through battling his own side. They spotted another file of armed men in different uniforms heading in the same direction as the Americans. Zais deployed his men to attack, then someone said, “Look! Some of them are wearing red berets!” They turned out to be some of Pritchard’s 2nd Parachute Brigade, who had also been dropped off-target. The two Allied groups joined forces and kept moving. They ran into a German convoy and at last could start doing their job. The Anglo-American force chewed up the German convoy with bazookas and machine guns, and all enemy troops were killed or captured.

Paratroopers and Germans were slugging it out all over the drop zone area, playing cat-and-mouse in the dark. American troops hollered the password “Lafayette,” expecting to hear the countersign, “Democracy.” Sometimes they forgot. Sergeant Leo Turco of Rochester, New York, stumbled alone through the dark until he heard a dark figure call out, “Is that you, Sergeant Turco?”

Turco lowered his Thompson submachine gun and said to Private Dan Rotundo of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, “For God’s sake, Rotundo, you’re supposed to call out the password, not ‘Is that you?’”

4,200 Sorties

One plan fell apart quickly. Lieutenant Jim Reith of the 517th was assigned to kidnap General Ferdinand Neuling, who commanded the German 62nd Corps, from his residence, the Villa Gladys, in Draguignan. The French Underground had an agent living right next to the villa, and she provided the Allies with all kinds of details on the general’s life and movements, even his breakfast routine—6 am precisely, two fried eggs, bacon, and toast.

But at 5:35 am, Reith and his crew were 20 miles from Villa Gladys, and the detailed plan came to nothing.

Still, the paratroops by and large did their job. All across the drop zones, paratroopers, individually or in groups, many wearing war paint and with their heads shaved, ambushed German convoys and couriers, blew up bridges, planted mines, and sprayed German patrols with gunfire. German survivors fled to report vast numbers of American and British paratroopers manning roadblocks, which created confusion at Neuling’s headquarters. Yet despite these efforts—Captain Bud Siegel led a successful attack on a German force that netted 60 POWs—Le Muy remained in German hands, and German troops began destroying the port installations at St. Tropez.

Glider-borne reinforcements were due at 8 am, but only the American gliders arrived. The British gliders could not be landed in the continuing fog shrouding their landing zones.

Meanwhile, the seaborne invasion got down to business. The minesweepers went to work at 5:15 am, clearing invasion routes. At 5:50 am, the Allied bomber force arrived to pulverize the 30-mile stretch of invasion beaches. As historian William Breuer wrote, “The ground shook and shivered and thrashed about under the enormous pounding. Gigantic orange balls of fire and gushers of earth shot into the air. Countless forest fires broke out. Wooden buildings were turned into splinters and stone structures into powder.”

Some 1,300 heavy bombers blasted the defenses for 90 minutes, raising a vast cloud of dust and smoke. The Allies flew more than 4,200 sorties in direct support of the assault.

At 7:30 am, the heavies wheeled home, but the naval bombardment began at 6:06 am, when the cruiser HMS Ajax fired the first shot of 16,000 shells from 400 Allied naval guns. Landing Ships, Tanks (LST) equipped with rockets hurled their missiles through the haze, drenching the beach with explosives. The bombardment smashed bridges across the lower Rhone, trapping the 11th Panzer Division on the wrong side. Watching through his binoculars, General Lucian Truscott exclaimed, “How can anything live under such a bombardment?”

At 5:55 am, loudspeakers blared, “Lower the landing boats,” and the transports began swinging out landing craft of all types, loaded with three infantry divisions. The loudspeakers followed with the command, “Assault troops to your boarding stations! Board your landing boats!” For some of the Americans who climbed down nets into landing craft, burdened with rifle and pack, it was their fourth invasion.

The 36th Infantry Division went in on the right, Major Carthel “Red” Morgan, of Amarillo, Texas, leading the 3rd Battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment ashore. A veteran of Salerno, he expected a rough invasion. His landing craft crunched as it hit the rocky slope of Green Beach at 8:03 am. But instead of heavy gunfire, the invaders were greeted by silence. “What do you want to do now, Major?” a sergeant inquired.

“Get the hell on inland as fast as we can and while we can!” Morgan yelled, and the troops moved in. Their advance was not checked, but at neighboring Blue Beach, Lt. Col. William A. Bird’s 1st Battalion of the 141st ran into automatic weapons fire and artillery, which sank three landing craft as they pulled off the beaches. Blue Beach was protected by an elaborate system of trenches. But the Germans were stunned, dazed, and demoralized by the heavy naval bombardment. As the Americans charged onto the beach, the exhausted Germans began staggering out of their trenches and bunkers, arms raised in surrender. Bird’s battalion began moving inland.

Chaotic Assault on Camel Red Beach

The 36th Division’s third assault, on Camel Red Beach, led to chaos and controversy. H-hour for Lt. Col. George E. Lynch’s 142nd Regiment attack was set for 2 pm, to provide time for warships, bombers, and minesweepers to wreck the defenses. Destroyers dueled with coastal guns along the Gulf of Frejus, and 93 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers hammered the Germans to little avail.

Next, Apex drone boats were sent in to explode underwater obstacles, and the remote-controlled devices ran around in circles. Truscott watched one of them that “went out of control, dashed wildly up and down the beach, turned out to sea to our consternation, then turned about again.” Two ran aground, and the destroyer Ordronaux sank one to avoid being rammed, two were boarded and put out of action, and only three exploded according to plan.

American Navy engineers claimed that German radio operators had “stolen” the radio direction of the “female” or explosive drone units from the “male” Apex directing boats. The Americans tried again with naval gunfire, bringing in the battleship Arkansas and her 12-inch guns along with two cruisers and four destroyers. Still the German batteries fired back, and most of the underwater obstacles remained in place.

Concerned with that, Rear Admiral Spencer J. Lewis, a Battle of Midway veteran commanding the assault force, tried to reach General Dahlquist, commanding the 36th Division, to discuss the situation. But Dahlquist had gone ashore to follow the battle and was out of touch. Out of options, Lewis took responsibility and ordered the Beach Red team to land at the already secured Beach Green.

As the landing force changed beaches, Truscott was stunned and furious—he had not been consulted on the move. Neither had Hewitt. Truscott saw the change of beaches as a threat to his timetable. A livid Truscott climbed into a landing craft and streaked to Green Beach to find Dahlquist.

When Truscott found Dahlquist, the senior general exploded. “Dahlquist, if you ordered that change I will relieve you, and if Colonel Lynch ordered it, I will try him by general court-martial!” Dahlquist told his boss the Navy ordered the change on its own, but Truscott was not happy. Truscott was less happy when he read a signal from Dahlquist to Lewis that read, “Appreciate your prompt action in changing plan…. Opposition irritating but not too tough so far.” Truscott called Lewis’s action “a grave error, which merited reprimand at least, and certainly no congratulation. Except for the otherwise astounding success of the assault, it might have had even graver consequences.”

As it turned out, the 36th Division did well, suffering only 75 casualties and capturing 236 POWs. The day after the landing, the 36th took Cap Frejus without much trouble.

The 3rd Infantry Division had a relatively easy time on the left compared to its previous assaults. It hit two beaches 13 miles apart and moved to pinch off the St. Tropez peninsula and its vineyards. When the German soldiers finally did emerge from their pillboxes, where they had holed up during the preliminary bombardment, they seemed dazed and surrendered quickly.

On Alpha Red Beach, the 756th Tank Battalion’s Duplex Drive Sherman tanks “swam” steadily to shore, providing the invaders with instant tank support. But when the Americans arrived, they found the Germans were gone, the trenches unmanned, the only defenses the active mines that kept exploding. By 8:50 am, Alpha Red Beach was secured.

The 15th Infantry Regiment came ashore at Alpha Yellow Beach, finding it dotted with bathhouses and elaborate fortifications held by Polish “volunteers.” It took an hour to clear the beach.

The 3rd Division achieved all of its objectives by nightfall and took 1,600 POWs while suffering only 264 casualties.

House-to-House Fighting in Sainte-Maxime

In the center, the Thunderbirds of the 45th Infantry Division, which included numerous Cherokee and Apache from Oklahoma and New Mexico, had to worry about narrow sea lanes as well as the enemy sandwiched between Alpha and Camel Beaches.

General Eagles’s men were to attack the beautiful Gulf of Saint-Tropez and the fashionable resort town of Sainte-Maxime, full of stucco villas that were now run down and shabby. The 45th Division’s men were veterans of Anzio, and when they came under German machine-gun and rifle fire, they methodically blasted German defenders out of pillboxes and bunkers with grenades and dynamite charges. The division stormed into Sainte-Maxime and spent two hours in house-to-house actions with rifles, bayonets, and grenades, digging the Germans out.

Sergeant Vere “Tarzan” Williams of the 157th Infantry had a feeling something was going to go wrong. He said later, “I was in the second wave that hit the beach and went on this hillside to get the rest of the company. There were mortar shells landing on the side of the hill, getting closer to us. Then one landed about 15 feet to my right. I felt something hit my leg, and I looked down but didn’t see anything. Then I saw the man in front of me and the one in back of me bleeding. One had his face bleeding and the other had his hand hit. I looked at my leg again and saw a hole in the pants leg. I opened my pants and saw blood running down my knee, so I took off my pack. The other men were laying on the ground, calling for the medic.”

Williams felt the Germans were zeroing in on their position, so he told the men the next round would land among them. They managed to move behind a large boulder, just as a German shell landed in the very spot where they had been standing. Williams was one of only seven casualties in the 157th on D-day, but his premonition saved his life.

After being temporarily patched up, Williams was sent to the rear and evacuated by sea. On the ship that took him back to Corsica, a sailor produced a bottle of champagne. “I can’t say that I like champagne all that much, but that really was good. The bottle was passed around twice for 11 men,” he said later. Williams recovered from his wounds and was soon back in action, long before his family got two telegrams—the first saying he was missing in action, the second that he was wounded in action.

In Sainte-Maxime, the fighting continued. Two Thunderbirds saw the swastika banner flying over the town’s railroad signal tower, shinnied up the pole, and ripped off the German flag and replaced it with Old Glory. Down below, sweating, weary Thunderbirds cheered as the Stars and Stripes fluttered in the breeze.

To clear out the town, the 45th brought in its tanks, which blasted open bunkers at a pointblank range of 50 yards, wrecking them. The division accomplished all of its objectives and took 205 POWs while suffering 109 casualties.

As the Americans moved ashore and inland, the Germans struggled to cope. General Neuling, the imperturbable commander of the German 62nd Corps, kept his uniform immaculate and his temper cool as the bad news flooded in. But he could not communicate with his forward units to order counterattacks. His only line was to Wiese’s headquarters 120 miles back at Avignon.

Wiese was also taking things calmly at his headquarters. The Allies’ objectives were obvious—Toulon and Marseilles—and everything depended on the 11th Panzer Division reaching that area in time. Their tanks had reached Avignon at dawn. Now it was a race to see who would get to the Riviera ports. The Germans did not know it, but they had already lost the race—all bridges between the Mediterranean and Avignon had been destroyed by Allied aircraft. Wietersheim would have to move his division across the Rhone by anything that would float. It would be four days before 11th Panzer could reform as a fighting unit east of the broad Rhone River.

Meanwhile, the Americans continued to advance. Captain Jess Walls and 250 paratroopers of the 509th Parachute Battalion hooked up with the 45th Infantry Division to attack an ancient, thick-walled citadel in the center of St. Tropez and brought up bazookas and machine guns. That seemed not enough to overcome the defenses, but the Germans hung out a white flag at 3:30 pm and surrendered the citadel. It took hours of house-to-house fighting to eliminate the German pockets. Some 130 Germans were captured or killed.

At 4:30, Truscott came ashore with his headquarters party at Sainte-Maxime. He asked his French liaison officer, Colonel Jean Petit, “Well, Jean, how does the soil of France feel to an exile?” Petit’s eyes were filled with tears, and he was too choked with emotion to reply.

Truscott got a briefing on the situation—the 45th was starting to hook up with the paratroopers and the three assault divisions were pushing inland—and said to an aide, “I guess this is a fitting celebration of the 27th anniversary of my original commission as an officer in the United States Army.”

Rough Landing For the Airborne

That afternoon, the troop carrier squadrons delivered reinforcements to the paratroopers on the ground—the 551st Parachute Battalion was airdropped into the landing zones. Pfc. Thomas B. Waller landed hard in a dry creekbed, shot at by Germans. Once on the ground, he cut his way out of his harness, assembled his rifle, and scrambled out of the creekbed. He then saw two Germans lying dead on their backs, staring sightlessly into the sky—the first German soldiers he had ever seen. He stared at them for several moments. Then he hustled to his company’s assembly area.

En route, he saw six German soldiers coming toward him. Waller raised his rifle and then lowered it. The Germans were prisoners being brought in by Waller’s company commander, Lieutenant Dalton, who had surprised them.

Another paratrooper, Lieutenant Dick Goins, had an equally odd encounter with the enemy. After landing in a cornfield, he looked up to see five Germans coming toward him. He was about to fire when they threw up their hands in surrender and offered Goins watches and rings to save their lives. They turned out to be Russian “volunteers” who had been told that American paratroopers were murderers and thugs who would kill any German who fell into their clutches. Goins simply took them prisoner.

After the 551st Parachute Battalion landed—mostly in the right place—337 glider tugs delivered the 550th Glider Infantry Battalion and the Japanese American antitank gunners. Night and overcast made for a difficult journey. Things got worse when the gliders slammed into huge wooden poles called “Rommel’s Asparagus,” the German name for anti-glider obstacles in the various fields chosen as landing zones. Gliders slammed into the ground at 90 miles an hour and were ripped into splinters by the tall wooden stakes. Lt. Col. Ed Sachs, who commanded the 550th, was hurled against the tubular wall separating the pilots from the soldiers, fracturing several of his ribs. The pain was terrible. He ignored pleas to be evacuated for medical treatment, recovered his map case from the wrecked glider, and hobbled off for his command post.

Technical Sergeant Ralph Wenthold of the 551st watched a glider land in an orchard, have its wings sheared off by two trees, smash head-on into another larger tree, and disintegrate. Bodies flew in all directions.

The flimsy gliders crumpled as they hit boulders, trees, and Rommel’s Asparagus. Of the 404 used in the assault, only 45 were deemed salvageable.

But the airborne operation had worked well. Frederick’s 1st Airborne Task Force, an ad hoc outfit, had suffered 450 killed, captured, and missing, and another 300 wounded. The actual parachute and glider drops had caused 290 casualties, most of them in the 550th Glider Battalion.

Frederick’s men were organized and in good shape, linking up with the seaborne forces. They had captured more than 1,000 Germans, and hundreds of dead Germans littered the roads and fields. The only weakness: the British 2nd Parachute Brigade had not taken the key crossroads town of Le Muy. Brigadier Pritchard claimed the Germans were too strong, even for his paratroops. Frederick ordered the newly arrived 550th Glider Battalion to take the town.

“This Has Been the Worst Day of My Life”

By midnight, with the Americans consolidating their positions and readying for new attacks, the German high command was facing yet another disaster in the West. In Rastenburg, East Prussia, Adolf Hitler stared down at his maps. The Führer had been listless and lethargic since the attempt to kill him on July 20, and his lack of energy suggested that he knew the war was lost.

The invasion of the Riviera was just another piece of bad news on a day full of reverses—the Russian Army was advancing remorselessly in Belorussia and western Poland, Eisenhower’s tanks were racing toward Paris and Germany, Allied bombers were pulverizing Germany’s cities nightly—and now this new invasion of southern France, and apparently no way to stop it. A gloomy Hitler looked up from his maps and muttered, “This has been the worst day of my life.”

Depressed but calm, Hitler told his generals that he was ready to consider whatever measures were necessary in the event that the situation in France continued to deteriorate. The generals were dumbfounded. Normally the Führer called for defense to the last man. Now he was willing to yield ground and save lives, even retreat to the West Wall on the German frontier. Perhaps he was recognizing defeat.

As August 16 began in southern France, the 550th Glider Battalion moved up to Le Muy to assault the small town that was the 1st Airborne Task Force’s prime objective. It was defended by 1,000 German soldiers dug in with antitank guns, mortars, and automatic weapons. The Germans realized the significance of the town and its road net and were determined to hold it.

The “Five and a Half” battalion attacked at 2:30 am, moving through British positions silently to obtain the advantage of surprise. They did not get it. As soon as the Americans reached the edge of town, the Germans opened fire with automatic weapons, cutting down the glider men. Sachs pulled back to reorganize and prepare for a daylight assault.

At 11:40 am, the glider gang tried again, using a flanking movement to encircle the town. A French Underground man pointed out a house to Lieutenant Paul Egan, and he and his five-man team rushed it. They captured seven German captains and a colonel hiding in the basement, while releasing an American paratroop officer and glider pilot who had been captured and were being held there. The Americans also captured the German aid station along with 33 wounded Germans and six medics.

The German defenders were soon swept up by the aggressive glider men, and the battle raged around the town’s church steeple, which dominated the nearby fields. Every time a shot rang out in Le Muy, the Americans shot at the church steeple, drenching it with lead, wounding by mistake Private Paul A. Stinner when he climbed into it to have a look around.

By mid-afternoon, the Americans had Le Muy along with 700 POWs, and 300 more Germans dead and wounded.

On the second day of the invasion, the French 2nd Corps began landing on the secured beaches with great emotion. “I kept my eyes closed so as not to be aware of too much happiness too soon,” said a French soldier of his homecoming. “And then I bent down and scooped up a handful of sand, with the feeling that what I was doing was a private act, separate from anybody else’s.” Many French soldiers had the same sense of exultation. A witness to one French landing saw the troops “massed in the bows of the ship, fascinated by the beach; they jumped down with a single bound, bent down to pick up a handful of sand, then skipped like madmen to the nearest pine trees, where they regrouped, shaking each other’s hands, or embracing like brothers, meeting again after a long absence.”

At La Nartelle, Hewitt, Patch, Forrestal, and Admiral Andre Lemonnier, chief of staff of the French Navy, came ashore, and a crowd emerged, seeing Lemmonier’s French hat, to welcome the liberators. Lemonnier made a short speech, but nobody heard it—everyone was too busy cheering.

The Franco-American invasion continued to expand its gains. The 517th Parachute Regiment fought to seize Les Arcs. The 36th Infantry Division pushed eastward along the Cote d’Azur toward Cannes and Nice. The Germans hit back with coastal batteries, so the Navy was called in. All night long warships and batteries exchanged salvos.

Now General Neuling was in personal danger—the American paratroopers were moving in on Draguignan. The German general was determined to hold his headquarters to the last man. The defense of Draguignan consisted of 750 men with no hope of reinforcements. Against this the 551st Parachute Battalion moved in for a night attack.

At 11 pm, the paratroopers attacked, charging through the fields and streets with ferocity. General Ludwig Bieringer, commanding the town’s defenses, was astonished at the speed of the American attack—his command post was quickly surrounded and he was captured at his desk. Bieringer, fearing the worst at the hands of tough paratroopers, offered them a one-mark bribe not to shoot him.

All night long the wild battle for Draguignan continued, but the Americans soon gained the upper hand. Two paratroopers captured an entire German hospital through bluff—they convinced the German lieutenant colonel commanding it that they had a large force of paratroopers ready to seize the building. By later afternoon of D+2, the Americans secured the town. With its capture, the 1st Airborne Task Force’s work was complete—all of its objectives had been taken and were being held.

Meanwhile, the last battle of the invasion was coming to a close. The Black Devils had yet to oust a band of Germans holed up in three stone Napoleonic forts on the offshore island of Port-Cros. Royal Air Force Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers and the cruiser USS Augusta had shelled the position for 48 hours to no avail. The British battleship HMS Ramillies steamed to within six miles of the target, pointblank range, and hurled 15-inch shells into the forts. Within a short time, white flags rose over the battered forts, and the Black Devils charged in to disarm the dazed defenders.

The Germans now faced the harsh facts— they could not drive the Americans into the sea. Fresh French troops were pouring into the beachhead, headed for Toulon and Marseilles. Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels readied the German people for the evil tidings with a broadcast that said, “We must be prepared for a German withdrawal from France. We must expect the loss of places with world-famous names.” Army Group G was in peril of being destroyed.

The French began moving in on Toulon and Marseilles, with the tough 1st Free French Infantry Division and the 3rd Algerian Division leading the assault. Marseilles and Toulon were liberated on August 28. Within a month, Marseilles’ great docks were supplying the advancing Allied armies. The campaign itself continued with Truscott trying to achieve a Cannae in the Rhone Valley and just missing. But the invasion of southern France reached its conclusion on September 11, 1944, when Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army linked up with the French at Saulieu, 40 miles west of Dijon.

“Gentlemen, We’re Here to Stay!”

The invasion of southern France was a fairly complete victory. The amphibious assault had gone in textbook manner, and the drive north covered 500 miles in one month. American casualties were 3,000 killed and missing and 4,500 wounded, while the French had 1,144 killed and missing and 4,346 wounded. Besides suffering far heavier casualties, the German armies lost 100,000 POWs, about a third of their total effectives in the south. More German troops were put out of action by Dragoon than in Tunisia. Blaskowitz was relieved of what was left of his command.

All that was left to debate was whether the invasion of southern France had been worth it. Churchill and Clark insisted that it prevented the Allies from freeing Eastern Europe, but Samuel Eliot Morison argued, “Unless the Allies managed to push the Germans beyond the Po, this operation would have had to start with an amphibious landing on the Istrian peninsula near Trieste. All naval planners, as well as the French and American generals, looked upon that with dismay. It would have meant thrusting a naval force up the long, narrowing and heavily mined Adriatic between enemy-held shores. The distance from Gibraltar to Trieste is 1,000 miles more than the distance from Gibraltar to Marseilles, and a Trieste operation would require about threefold the shipping to support the same number of troops as an invasion of Southern France.

“Even if the Germans were routed out of Italy so that no amphibious landing near Trieste were necessary, the obstacles to sending a military force from the Adriatic to the Hungarian plain were tremendous. The so-called Ljubljana Gap is an area between the Julian and the Dinaric Alps where the mountains are not quite so high as they are to the north or the south. A route through it had been developed by Austria in the 19th century to link Vienna with Trieste. Between them, passing through Ljubljana, a double-track railway and a 20-foot-wide road had been constructed. The highway was very winding and poorly surfaced, with gradients up to one in 10, and it crossed two 2,000-foot passes dominated by much higher mountains…. Mr. Churchill in his arguments against Anvil, and even the official historian of British Grand Strategy, stressed the ‘rugged nature’ of the Rhone valley up which troops there committed would have to march; but the route north from Marseilles is an open speedway compared with the Ljubljana route to Vienna, which Mr. Churchill seems to have viewed as a sort of Sherman’s march through Georgia in reverse.”

British historian Max Hastings has a simpler view: “Though Eisenhower is often, and sometimes justly, criticized for lack of strategic imagination, he and [U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C.] Marshall were assuredly right to insist upon the concentration of force in France.”

As matters developed, Marseilles and Toulon were critical to the Allied advance. The two ports injected 905,000 American soldiers and 4.1 tons of matériel into the advance. With the loss of southern France, the Germans were forced her to go to the defensive on their own border. Churchill may have had reservations about the campaign, but Marshall had none. He called Dragoon “one of the most successful things we did.”

All the analysis was in the future. On the night of August 17, Truscott took up his headquarters outside Saint-Tropez. He reviewed the messages from his commanders and said, “Gentlemen, we’re here to stay!”

The entire war policy by the US and Britain was handle poorly. Churchill’s fear of Hitler prompted an accommodation with Stalin that was certainly not necessary to the degree it went, especially considering the eventual resources of the Commonwealth. Roosevelt remarked several times that he could handle “Uncle Joe”. Considering both his condition during and after 1943, and the fact that he was surrounded by Russian sympathizers, little wonder that Stalin got almost all he wanted. All of these negatives were compounded by a shortage of real wartime experience of many on the general staffs of the US and Britain. Had it not been for some outstanding field commanders who took it upon themselves to exercise initiative and and a hard headed view to results, the war could have ended with even worse political consequences. Example: WW I.

What is missing from this article is how badly Ike blundered (a second time) by reigning in Gen. Jacob Devers’ 6th Army Group plan to cross the Rhine in late November 44′ above Strasbourg with overgrown undermanned defenses on the opposite bank. His troops were fully supplied and already trained in river crossings with more than enough amphibious vehicles to achieve it. Had he been unleashed, a fresh juggernaut would have raced up the east bank rolling up the German left flank; trapping them on the west bank to surrender or be annihilated. Ike pulled back on Patton at Falaise to wet nurse Monty’s impotent progress south of Caen losing the opportunity to bag an entire German army that came back and mauled Montgomery in the Market Garden Fiasco. Ike pulled back on Devers because Devers wasn’t a “Club Member”. Some surmise the Germans would have been ready to sign in February had Devers been green lighted and 50,000 allied casualties would have been avoided. Twice, Ike bet on the wrong horse for either political or personal reasons with disastrous results.

Well hind-site is 20/20 no doubt about it. Arm chair generals are a dime a dozen. Who can judge a commander who made mistakes ,just like all people, but won the war. If they knew then what we know now the German people would have strung up Hitler in 1923. Unless you know what Ike did or didn’t know or were in his shoes try to judge less harsh if your being honest.

It’s easy to cast blame long after the fact: In a massive battle such as this, the fact that it ended just as had been planned says all that needs to be said.

All the arm-chair generals can nit-pick to their heart’s desire, but the fact remains that the Germans were routed, and we won.

The only question really is, why was all this necessary in the first place?

Just the rantings and ravings of a mad-man, or delusions of a narcissistic lunatic, bent on world domination, was the cause of it all.

If only somebody could have gotten to him early on, and snuffed out the existence of the power-mad “fuehrer,” it would have saved the world more than 60 million lives.