By Chuck Lyons

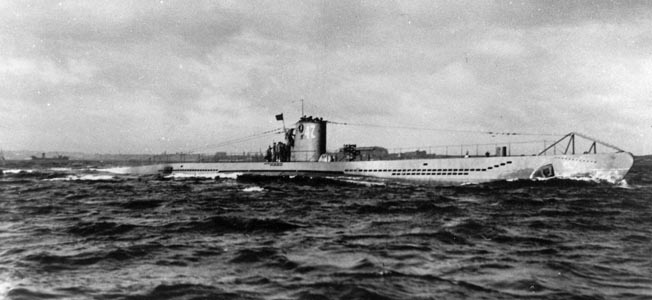

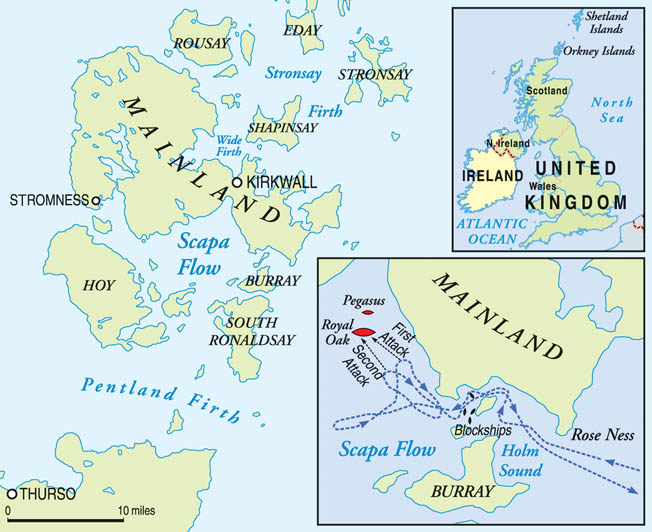

In October 1939, illuminated by the northern lights, the German submarine U-47 threaded its way through sunken barriers and slipped into the British anchorage at Scapa Flow, a 125.3-square-mile natural port off the northern coast of Scotland, in the Orkney Islands.

Penetrating the anchorage had long been an unrealized German dream, one that U-boats had attempted twice in World War I; both times they had failed. One U-boat had been rammed and run aground and the second destroyed with all hands.

But now, at last, a German submarine slid quietly across its surface.

U-47 and its 31-year-old captain, Günther Prien, moved across the anchorage from the east where they had entered and then turned toward the north, searching for targets. Prien was surprised at how few British ships were in the area.

He had expected hundreds and was unaware that Sir Charles Forbes, commander in chief of the British Home Fleet, had become concerned by German aircraft recently spotted in the area and had ordered most of the fleet to disperse.

Finally, a lookout on U-47’s bridge spotted a small cluster of ships including the 1914 battleship Royal Oak silhouetted against the northern lights.

Unknown to Prien and the crew of U-47, the 29,000-ton Royal Oak had just returned to Scapa Flow after a battering from storms in the North Atlantic. Some of her smaller caliber guns had been rendered inoperable by flooding and many of her life rafts had been seriously damaged. Because of her condition, Forbes had decided to keep the Royal Oak in Scapa Flow to provide added antiaircraft fire if needed.

In the darkness, U-47 slid toward the big ship.

The Royal Oak, like Scapa Flow itself, was a veteran of World War I, but by the outbreak of World War II, the 25-year-old ship was no longer considered fit for modern combat. She had been launched in 1914, had seen battle in 1916 at Jutland, and had later served as part of Britain’s Atlantic, Home, and Mediterranean Fleets.

At the end of World War I, Royal Oak had also served as escort to several German vessels that had surrendered and were interned at Scapa Flow, which had been used by ships since prehistory.

In 1904, in response to the German naval action, British naval planners had decided a northern base was needed to control access to the North Sea. Scapa Flow was chosen, and the area was reinforced with minefields, artillery, and concrete barriers.

Primarily because of its distance from German airfields, Scapa Flow was again selected as a main British naval base when World War II broke out. By then, however, the defenses built earlier and during World War I had fallen into disrepair and new “block ships” were sunk in an attempt to block the Flow’s three entrances. Navigable channels remained, however.

German Commander of Submarines Commodore Karl Dönitz, who had commanded a submarine in World War I and who had developed the German Rudeltaktik (“wolf pack”) submarine attack tactic while a British POW, decided early in the outbreak of hostilities to attack the Flow.

Such an attack, he realized, could, if successful, force the British Home Fleet out of Scapa Flow, thus lessening the British hold on the area and allowing greater German access to the North Atlantic and the convoys that sailed there with supplies for the United Kingdom.

Such an attack would also be seen as an act of vengeance for the ships of the German High Seas Fleet that had surrendered at the end of World War I and—like those escorted by the Royal Oak—had then scuttled themselves in Scapa Flow.

In addition, Dönitz believed, the propaganda value of the attack and its effect on British morale were inestimable. In a single attack, Germany could bring the war to Britain and show the British that even their home waters were not safe from German aggression.

Dönitz was aided in his planning by aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by German aeronautics pioneer Siegfried Knemeyer, who received an Iron Cross for the mission that supplied the photos. (Knemeyer’s flight may have been the aircraft that had moved Forbes to scatter the fleet.) Dönitz also handpicked U-boat Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien as commander of the actual attack.

Prien was a loyal member of the Nazi Party and had in fact been called “the most Nazified U-boat captain.” He had been at sea in the Merchant Marine and the German Navy since he turned 21 and, by the end of the war, would be credited with sinking or seriously damaging 40 Allied ships. At the time of the Scapa Flow mission, however, he had been in command of U-boats for less than a year. The Scapa Flow attack was only his second patrol of the war.

The proposed raid was scheduled for the night of October 13-14, 1939, when the tides would be high and the night moonless. U-47 approached the British base a little after midnight through the narrow approaches of Kirk Sound, the most easterly of the three entrances to Scapa Flow.

Staying on the surface, Prien first sailed toward the southeast across the Flow and toward the island of Hoy before realizing a navigational error had the submarine heading toward some dangerous shoals. Prien turned to the north, spotting what appeared to be several ships anchored in that area. (Fifty-one ships––18 of which were combat vessels––were reported to be in Scapa Flow at the time.)

“It was absolutely dead calm in there,” Prien later said. “The entire bay was alight because of bright northern lights.”

Sailing north between the sunken block ships Seriano and Numidian, U-47 grounded itself temporarily on a cable strung across the channel from the Seriano and was briefly caught in the headlights of a taxi onshore, but no alarm was raised in either incident.

As U-47 moved north, a lookout on the bridge spotted the Royal Oak about 4,400 yards to the north and correctly identified the ship as a battleship of the Revenge class. Mostly hidden behind her was a second ship, only the bow of which was visible to U-47. (Prien misidentified that second ship as a battlecruiser of the Renown class, but it was later determined to be the World War I seaplane tender Pegasus.)

The submarine quietly approached the Royal Oak and fired a three-torpedo spread, then turned quickly to escape.

One of the three torpedoes struck the Royal Oak’s bow at 12:58 am, and the dull thud and muffled explosions of its detonation confused the sailors onboard. Most thought the cause was an internal problem on the ship, perhaps in the paint locker. The hit caused little damage other than severing the Royal Oak’s starboard anchor chain.

When Prien realized there was no surface or air reaction to his attack, he fired a torpedo from his rear tube, but this torpedo also missed the battleship. He then turned U-47 back to the north and fired another array of three torpedoes, hitting the Royal Oak amidships at 1:06 am.

“There was a bang and the next moment the Royal Oak blew up,” Prien said. “The view was indescribable.” (Kept secret by the German naval command when it jubilantly announced the attack was that several of the torpedoes fired by Prien failed to strike the Royal Oak or to detonate because of long-standing problems with their depth steering and magnetic detonator systems. These problems continued to bedevil the German submariners.)

The Royal Oak heeled over from the force of the explosions, and its gun barrels shifted with the heel, pulling the ship even more quickly onto her side. All her lights went out as the power failed. Water poured in through the gaping hole in her side and through the hatches, which were all open at the time, standard practice for a ship in port.

Men asleep in their bunks or just lying there were trapped by the speed of the deluge. In minutes the Royal Oak was going down, and those few men who had been able to get on deck were in the freezing water swimming through a thick oil slick.

“It was so cold that I was told that it was colder than the inside of a fridge,” one survivor later said.

Meanwhile, U-47 turned away to the east and slipped out of Scapa Flow by the same channel it had used to enter the British anchorage. The Royal Oak continued to take on water and finally disappeared below the waves at 1:29 am, only 13 minutes after U-47’s second successful hit.

After the sinking, Prien and his crew reached the German North Sea port of Wilhelmshaven on October 17 and were immediately greeted as heroes. Hitler sent his personal airplane to ferry the crew to Berlin, where each man aboard U-47 was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class. Prien received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, Germany’s highest military award. It was the first time the award had been made to a German submarine officer.

Prien was later nicknamed “the Bull of Scapa Flow,” and his crew at one point decorated U-47 ’s conning tower with the painted image of a snorting bull, which later became the emblem of the 7th U-boat Flotilla. Prien also found himself in demand for radio and newspaper interviews, and his autobiography, ghost-written by a German journalist, was published the following year.

Of those men in the water who attempted the half-mile swim to the nearest shore, only a handful survived. Many more were rescued by the tender Daisy 2, which had been tied up for the night to Royal Oak’s port side.

When the Royal Oak was hit and began to list, Daisy 2’s commander, John Gatt, quickly cut his ship clear, snapped on his floodlights, and began picking up survivors, managing to pull 386 men from the cold water, including the Royal Oak ’s commander, Captain William Benn. Rescue efforts continued until nearly 4 am.

Out of the Royal Oak ’s complement of 1,234 men and boys, 833 were killed that night or died later of their injuries. Among that number were 126 “boy sailors,” young men under the age of 18 who were stationed on the ship.

“I was a very lucky man [to survive],” said survivor Bert Peacock, who was 17 years old at the time of the attack.

Immediately after the sinking, there was confusion—and sometimes wild speculation—as to what had caused the sinking. It was only when divers descended to the wreck and discovered the remains of a German torpedo that the cause was confirmed as having been a U-boat attack.

That confirmation was nonetheless followed by additional speculation including a rumor that a local German spy had paddled out into Scapa Flow and led the U-boat into the harbor, a rumor that was labeled “nonsense” by the authorities.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, announced the attack to the House of Commons, calling it “a remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring”––an indication of the more gentlemanly attitude taken by both sides at that stage of the war.

Six months later, the commander of a German heavy cruiser sank a British destroyer off the coast of Norway, stayed on the scene to rescue 31 British seamen, congratulated them on putting up a good fight, and then recommended the British captain for a Victoria Cross. It is said to be the only time in British history that the award was given on the recommendation of an enemy.

In his announcement to the Commons, Churchill said the sinking of the Royal Oak would have only a minor effect on British naval readiness and answered questions including several as to why so many “boy sailors” were aboard the Royal Oak.

Three days after the U-47attack, four Luftwaffe Junkers Ju-88 bombers also raided Scapa Flow in what was one of the first bombing attacks on Britain during the war. The attack badly damaged the battleship HMS Iron Duke, and one German bomber was shot down by an antiaircraft battery during the attack.

There exists an underlying and as yet unresolved mystery about the attack.

When Captain Prien reported on Scapa Flow, he stated that he had sunk the Royal Oak and that he had also torpedoed a second ship that night, a ship he identified as the battlecruiser HMS Repulse. The Repulse, however, had left Scapa Flow earlier in the day. Researchers have suggested that U-47 may have instead hit HMS Iron Duke, the British Atlantic Fleet’s flagship, the same ship later attacked by the four Ju-88 bombers. When those planes arrived at Scapa Flow on October 17, the Iron Duke already lay beached on Hoy Island and was reported to have a large hole in her bow.

The British Admiralty, however, never confirmed that HMS Iron Duke had been hit by a torpedo, possibly because it was considered too sensitive to report that the fleet’s flagship had been attacked by a German submarine inside a British anchorage.

A Board of Enquiry held shortly after the Royal Oak sinking found that there were 11 possible submarine routes into Scapa Flow still open. It also uncovered information that junior officers at the base had complained that Scapa Flow was not safe but that senior officers had chosen to ignore these views.

Admiral Sir Wilfred French, commander of the Orkney and Shetland Isles, was eventually held responsible for what had happened and was put on the retired list despite his insistence prior to the Royal Oak sinking that Scapa Flow needed additional safeguards. History has labeled the blame put on French as “unjust.”

In addition, when it became public knowledge that 126 of the 163 “boy sailors” on the ship had been killed—a fatality rate of 77 percent—it became generally accepted in the British Navy that the centuries-old practice of allowing young men under the age of 18 to serve on warships should be discontinued in all but the most exceptional circumstances.

In Germany the raid was celebrated as a triumph, and Commodore Dönitz was promoted to rear admiral. The sinking of the Royal Oak, which was the first of the five Royal Navy battleships and battlecruisers sunk in World War II, while having little effect on the naval superiority of the British, did establish, as Admiral Dönitz had envisioned, that the anchorage British planners had considered impregnable was in fact vulnerable, and it gave a solid body blow to British morale. The German Navy had shown it was capable of bringing the war home to Britain.

In the very last days of the war, Dönitz was named the last president of Germany, replacing German Führer Adolph Hitler after the latter killed himself on April 30, 1945.

Scapa Flow, which was capable of holding the entire Grand Fleet, was temporarily abandoned until its defenses could be improved, but it eventually became the main British naval base of the war. New block ships were sunk, booms and mines were placed over the main entrances, coast defenses and antiaircraft batteries were installed, and Churchill ordered the construction of a series of causeways to block the eastern approaches to Scapa Flow. They were built by Italian prisoners of war being held in Orkney.

In the months following the attack on the Royal Oak, Captain Prien and his crew continued to prove themselves one of Germany’s top U-boats. On their sixth patrol in June 1940, for example, they sank eight ships for a total of 51,483 tons of Allied shipping lost.

U-47 was last heard from in March 1941.

A radio message was received from her on the morning of March 7, sent from the North Atlantic near the Rockall Banks, west of Scotland. It was her last message. She is presumed to have been sunk there by the British destroyer HMS Wolverine and lost with all hands—including her commander, Günther Prien.

Today the Royal Oak, still lying beneath the waters of Scapa Flow, is a recognized war grave, and each year on October 14, a team of Royal Navy divers descends to the wreck. There they fly the Royal Ensign from her overturned hull.

Love the stories I’ve read previously. Looking forward to more features.