By Ron Smith

BACKSTORY: In World War II, the American submarine force was inordinately small—just 252 total boats, compared to the more than 1,100 deployed by Germany and over 600 built by Japan. Yet, the American subs, most of which saw service in the Pacific, accounted for 54.6 percent of all Japanese naval and merchant ships sunk. However, in compiling these statistics, the U.S. Submarine Force suffered heavy casualties—over 3,400 men (22 percent of the force) killed and 52 subs lost.

Although he was only 17 when he enlisted with his father’s consent in the U.S. Navy in the summer of 1942, John Ronald Smith (called “Ron” or “Smitty” by his friends) of Hammond, Indiana, was eager to pay back the Japanese for Pearl Harbor. After qualifying as a submariner following boot camp, he became a torpedoman in the aft torpedo room (the “caboose”) of the Salmon-class USS Seal (SS-183)––at a time when the American torpedoes were almost criminally unreliable and the U.S. Submarine Force was still trying to prove itself.

This article is adapted from The Depths of Courage: American Submariners at War with Japan, 1941-1945, by Ron Smith and Flint Whitlock.

“Battle Stations Submerged!”

At 7 am on May 4, 1943, as part of the crew aboard the U.S. submarine Seal was eating breakfast, the alarm was sounded: “Battle stations submerged!” A Japanese convoy had been spotted on the surface. The motormen shut down the diesels, the electricians in the maneuvering room switched to batteries, and the sub glided silently beneath the surface.

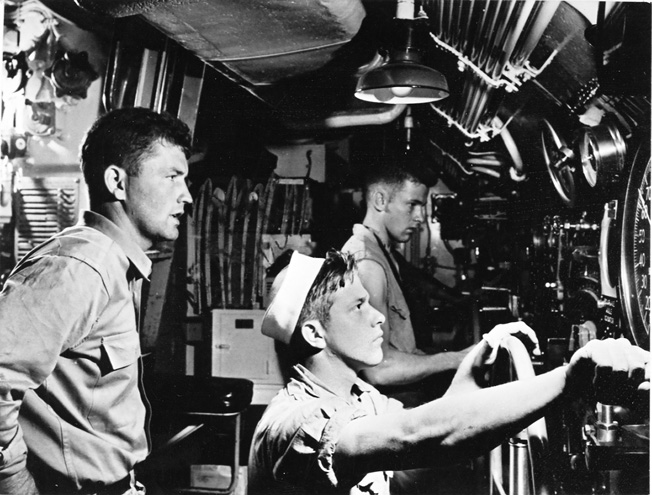

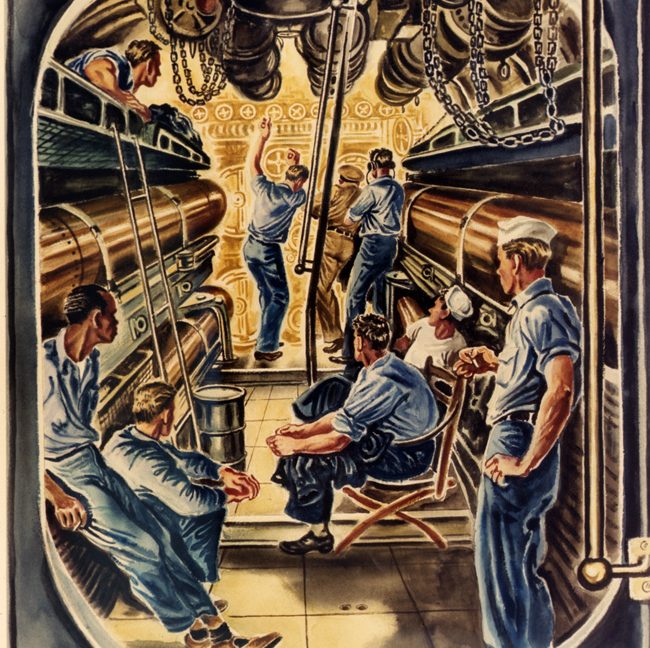

All routine activity aboard Seal ceased as every man hustled to his battle station. In the aft torpedo room, the men quickly removed the bunks and stowed them in the aft engine room. Horizontal I-beams were then swung into place across the room, front and rear, to support the four extra torpedoes in the room in the event reloading was necessary. Smitty took up his battle station seated between the aft tubes, eyes focused on the TDC—the torpedo data computer transmitter—mounted on the rear bulkhead, with headphones on his ears, a microphone pressed against his throat.

While the sub continued on its way to the intercept point, Smitty glanced around at his fellow sailors in the tight space—a scruffy, unmilitary looking lot. All wore ragged, cutoff dungaree shorts; sandals, no socks; an assortment of dirty skivvy shirts with the sleeves cut off or brightly colored Hawaiian shirts. Everyone was dripping with sweat. A few covered their stringy, unwashed hair with dark blue Navy baseball caps. Those old enough to shave had full beards; a few young guys, like Smitty, sported the first scraggly suggestions of facial hair. Yet, each man was a pro, an expert at his deadly craft.

There was short, muscular John “Big Ski” Kaczmerowski, looking confident, like a quarterback in a close game. Behind him, acting as backup, was Maylon “Woody” Woodard, a reliable man in a sub-versus-ship duel. There was skinny Dillingham, nicknamed “Seagull,” a torpedoman without peer. Two other sailors, one named Brown and the other nicknamed Dead Eye, stood by, ready to lend a hand and their considerable muscle with the reloading. Each man had an insouciant, almost cocky look to him, as if to say, “No big deal; we’ve done this a hundred times before,” masking any tension they might have felt and helping calm Smitty’s tightening stomach.

“Fire One, Fire Two, Fire Three”

Lieutenant John Haines, in the control room amidships, had already begun the plot as Seal moved to intercept the convoy. The TDC was being fed the distance, angle, and speed of the target, information that was entered into the torpedoes’ primitive “brains.” It was Smitty’s job to line up the marks on the dial of the TDC transmitter to the ongoing into the “tin fish;” he would push the big brass firing lever only if, after receiving the command to fire, the marks, or “bugs” as they were called, were perfectly aligned. An accurate plot would make the fish more likely to hit their targets, but, due to countless malfunctions, no one could be certain, even if the bugs were right on, that the torpedoes would actually detonate.

Over the headset, Haines, referred to as “Control,” alerted the other 58 officers and enlisted men in Seal to stand by for action; Smitty passed this news along to those around him. While the forward torpedo room was put on alert, the aft torpedo room was told to stand easy—for now.

Once the range and distance to the target—a fat oiler with the distinctly un-Japanese name of San Clemente Maru—had been entered into the TDC, the order to “Fire one” was given to the forward torpedo room, and the boat suddenly lurched as though it had collided with a brick wall.

“Fire two, fire three.” Two more lurches as 2,000 pounds of compressed air pressure from the “impulse bottle” violently kicked the tin fish out of their tubular homes.

“Lumpy” Lehman, the sonar man, reported over the circuit, “All fish running hot, straight, and normal.” Lehman had an amazingly sharp, discriminating set of ears; he could detect the faint shooshing of screws from as far away as 20 miles and tell the officers how many ships there were, what types of ship were in the convoy, how fast the ships were going, and even in what direction they were heading. Some wags aboard Seal swore Lumpy could even tell what the registration numbers of the ships were.

Waiting For Impacts

Now they all waited. Would the torpedoes strike home, or would there be nothing but silence? Some men crossed their fingers or fingered the crucifixes that hung from their necks or played with some other sort of talisman thought to bring them luck.

A few of Seal’s crew may have given a moment’s thought to the enemy sailors at whom the torpedoes were being directed, oblivious that their world was about to be shattered, that their lives were about to come to a sudden and violent end. Like the Americans, these sailors had girlfriends, wives, mothers, fathers, and children back home.

Like the Americans, most of these sailors were just doing a job that someone in higher authority had decreed they must do. Like the Americans, most of these sailors would have preferred spending their youth in other, more peaceful pursuits. But the Americans felt it was not healthy to dwell on such thoughts, to think of the enemy in human terms.

No, the business of war demanded that they think of the enemy as exactly that—the enemy—and attempt to kill as many of them as possible. After all, it was the Japanese who had bombed Pearl Harbor without warning; the Japanese who had brutally invaded Korea and China and Malaysia and the Philippines; the Japanese who had turned thousands of Korean girls and young women into their sex slaves; the Japanese who had beheaded captured Australian and British and American soldiers and airmen; the Japanese who had slaughtered their American and Filipino POWs along the march from Bataan; the Japanese who had committed atrocities every bit as horrible as those being perpetrated by the Nazis on the other side of the world.

And so the men inside Seal pushed such thoughts—if they had them—out of their minds and waited with eager anticipation to hear the explosions that would signal that the despised Japanese enemy sailors were plunging in agony to their deaths.

The men in the aft torpedo room focused on the second hand sweeping around the shiny bulkhead chronometer. “First one missed,” Woody muttered as the time for the intercept came and went. The second and third torpedoes also passed into the silence of failure.

“Tubes Aft, Stand By”

Seal’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Harry B. Dodge (USNA, 1930), swung the sub around so the aft torpedoes could be fired while the forward torpedo room reloaded, and Smitty heard Lieutenant Hanes’s voice in his headphones say, “Tubes aft, stand by.”

“Tubes aft standing by,” Smitty replied, making his posture just a little more erect, a little more military. “Stand by,” Smitty repeated for the benefit of his crewmates. Here he was, the newest and youngest member of the crew, issuing orders to these “old salts.” He was at last being given a chance to show what he could do. He hoped he would not fail this, his first big combat test.

The crewmen moved quickly to their firing stations. They had no idea what their target was—a carrier, battleship, cruiser, destroyer, oiler, tanker, freighter, or transport—nor did it particularly matter.

“Tubes aft, stand by five, six, and seven,” said Haines.

“Tubes aft, standing by five, six, and seven,” repeated Smitty.

Haines directed, “Tubes aft, open outer doors on five, six, and seven.”

“Tubes aft, aye,” said Smitty, and repeated the command for Big Ski and Seagull. They opened the valves from the “water round torpedo”—a tank located just below the torpedo tubes—and flooded the three firing chambers with seawater to equalize pressure to the sea; the fourth aft tube, number eight, was normally held back during an attack.

“Control,” Smitty reported, “outer doors on five, six, and seven open.”

“Tubes aft, switch on firing circuits on five, six, and seven,” said Haines, and Smitty repeated the directive.

Seagull threw the switches that armed the torpedoes, then gave Smitty the “okay” sign. “Firing circuits on for five, six, and seven,” Smitty told Haines.

“Very well, tubes aft. Set depth 12 feet.”

“Set depth 12 feet, tubes aft, aye,” Smitty said as the dials on the tubes were set to the depth ordered.

“Stand by five,” Haines said.

“Stand by five, tubes aft, aye.” Smitty watched the dials and waited for the marks on the TDC to line up.

“Fire five.”

As the bugs came into alignment, Smitty mashed the tube’s firing button at the same moment that Hanes, 50 yards away, pushed the firing button for number five, making sure that the torpedo fired even if the electric circuit failed.

There was a loud whoosh of compressed air, a deep-throated boom, and a spray of water that spurted into the compartment from around the tube’s gasket as the torpedo was launched.

The same procedure was followed for tubes six and seven, although Smitty was angry at himself for launching number six just as the TDC marks went out of alignment by two degrees; he knew that number six would miss its target.

Big Ski, cussing a blue streak, was having trouble with the number seven tube’s gasket right after the fish was fired. An eight-inch stream of water was pouring in and sloshing down into the bilges. Not a critical problem yet, but one that couldn’t be ignored.

“Hit the emergency valve,” Woody yelled over the noise of the rushing water. “Shut ‘er down!”

Big Ski moved over to tube seven and with great effort turned the manual control wheel. The stream of water was gradually pinched off, but not before Ski was a soaking, dripping mess.

“Tubes aft, close outer doors,” Haines commanded.

“Tubes aft, close outer doors, aye,” Smitty relayed, and Big Ski and Seagull cranked the outer doors closed.

“All fish running hot, straight, and normal,” reported Lumpy Lehman on sonar.

“We Hit the Son of a Bitch!”

Then someone who was clocking the first torpedo announced that it had missed. The crew in the aft torpedo room slumped. Damn these defective fish, they collectively thought.

A few seconds later there came a thumping roar followed by a jolt that felt as if the sub had been struck with a giant sledgehammer.

“We hit the son of a bitch!” shouted Big Ski. It was torpedo number six, the one Smitty knew for sure was going to miss.

The crew members began whooping and hollering and jumping up and down and slapping one another on the back, just as if their team had scored the winning touchdown. How lucky can you get? wondered Smitty to himself.

“Tubes aft,” said Haines, “start your reload. And good shot, Smitty.”

“Tube aft start reload, aye,” said Smitty. “And thanks, Haines.” (Except for the skipper, submarine sailors did not call the officers “sir” or by their ranks.)

The periscope was raised, then lowered. Frank Greenup, the executive officer, came over the intercom. “We just sank a large transport freighter,” he announced. “Looks like a lot of men in the water.”

Cheers erupted again in the aft torpedo room, and more celebratory dances were conducted. The crew gave Smitty a new nickname: “Warshot.”

Infantrymen can tell if their bullets are hitting the target just by looking; artillerists, too, can watch the results of their salvos. Airmen on bombers can scan the landscape below and note their bombs striking home, and gunners on surface ships can observe the havoc their shells cause. But submariners, with the exception of the officer manning the periscope, are denied visual confirmation of their marksmanship and must rely on aural evidence alone.

But even without sonar headphones, the men in Seal could hear the 7,354-ton San Clemente Maru breaking up as it sank. Then the boilers exploded—Ka-THWOOMP! Ka-THWOOMP! The shock waves hit Seal, shaking her and rattling the chinaware in her galley. Then they heard the cracking and popping noises as the freighter’s bulkheads caved in while the ship sank deeper into the ocean. So that’s what a dying ship sounds like, Smitty said to himself with morbid fascination.

200 Feet Below the Sea

Greenup broke into the crew’s reverie and celebrations: “There are two escorts up there looking for us now. Rig for depth charge. Rig for silent running. Close all watertight doors.”

Without wasting a second, Seal’s crewmen did what they had practiced a thousand times. The watertight doors between compartments were swung shut on their heavy hinges and dogged down. The bulkhead flappers that passed air between compartments were closed. Big Ski climbed up into the escape hatch to make sure it would not spring open from the shock of the depth charges and flood the interior. The air conditioning was shut off.

Seal plunged to 200 feet, where the oceanic pressure on the hull was 90 pounds to the square inch, and the electric motors were silenced so that not even the slow turning of the propeller screws would give their position away. Talking, walking around, dropping a tool, doing anything that might make the slightest noise was strictly verboten. This was the moment every submariner dreaded. The worm had turned; the hunter had become the hunted.

While they sweated it out down below, Seal’s crew knew that the enemy’s destroyers were crisscrossing above them, doing their best to locate them. Sonar operators on the destroyers, using submarine-locating equipment, were “pinging”—sending electronic signals into the deep water and listening for the telltale echo that would tell them a large metallic object was down there.

Once that echo was heard, depth charges would begin to cascade down on the immobile prey. Sometimes there would be only a handful of charges; at other times the depth charging would go on for hours. No one could be certain when—or how—it would end.

Japanese depth charges were generally regarded as less powerful than the American variety—containing 242 pounds of explosive and detonating at a relatively shallow depth—about 150 feet at the maximum.

By diving to 200 feet or more, the submarines were relatively safe, but not always. The charges could still be plenty lethal; no one knew how many submarines did not return because a lucky shot had split the pressure hull or damaged the propulsion or steering mechanism or wrecked a valve on a ballast tank, making it impossible for a sub to gain positive buoyancy and return to the surface.

The Thunder of the Depth Charges

Smitty and his mates in the aft torpedo room suddenly discovered they had a problem—a big one. When the order to rig for depth charges came, torpedoes had already been loaded into tubes five and seven, but the torpedo for tube six was only halfway in. As Seal dove to 200 feet, the outer pressure compressed the steel hull just enough to make it a tight fit for the torpedoes; consequently the torpedo in number six tube was stuck.

Everyone knew that a depth charge going off near the stern might jar open the outer door to tube six and cause a sudden inrush of seawater. If the blast were severe enough, it might even rip the outer door off its hinges, blow the torpedo back into the compartment, and cause the aft torpedo room to flood, killing everyone in the sealed-off compartment and making it hard, if not impossible, for the sub to surface. The crewmen manhandled the tin fish, trying to shove it home, but it wouldn’t budge.

Somebody had once told Smitty that he would hear a click just before the depth charge detonated; it was the trigger mechanism and would give those in the boat only a fraction of a second to grab something, grit their teeth, and hang on. Then it happened.

Click … KaBLOOM!

As feared, a depth charge went off close to the stern and water immediately began pouring into the compartment from around the protruding torpedo. Click … KaBLOOM!

Another one, then another. The lights flickered off and on, and the whole sub lurched and rocked as though some giant sea creature were pummeling Seal with its monstrous fists.

Click … KaBLOOM! With each explosion, the glass faces of gauges throughout the sub shattered. Lightbulbs popped, sizzled, then went out. Cork insulation and chips of paint flew. Cockroaches scurried for safety. The boat’s welded seams seemed ready to split apart, and water continued to gush in from around the half-inserted torpedo.

“Get that goddamned thing in there before the whole ocean pours in!” yelled Woody. Brown and Dead Eye did their best with the block and tackle, but the tin fish wouldn’t move. Five-feet, five-inch Big Ski went to lend a hand, grabbing the line in front of Dead Eye, but Dead Eye called him a dumb Polack and shoved him out of the way. Big Ski slipped on the wet deck and came up with a tube-door crank in his hand, ready to split Dead Eye’s skull. Dead Eye grabbed a mallet, and for a minute it looked as if the two Americans had declared war on each other.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Two more charges went off nearby, shaking Seal violently and bringing the two combatants back to their senses. More water gushed in; the outer door could blow at any moment.

Big Ski dropped the crank handle, shoved past Dead Eye and the others, and yanked the chock and block and tackle from the rear of the torpedo. He then pulled a wiping rag from his back pocket, placed it against the rear of the fish, and, grunting and straining with almost superhuman effort, shoved the torpedo fully into the tube all by himself. Everyone watched with stunned disbelief. It was a miracle; no one, especially not someone five-feet-five, could do that alone.

Click … KaBLOOM!

Coming out of his momentary stupor, Seagull Dillingham slammed shut the inner door to tube six as Smitty cranked it around into the dogs and locked it closed. Exhausted, Big Ski dropped to the deck, sitting with his head between his knees, sweating hard, his breath coming in clumps, the veins in his neck bulging like snakes. Everyone moved around him cautiously and quietly, not daring to say a word.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

The depth charges continued to rain thick and fast, and Smitty prayed that they would soon cease. After another 10 or 15 explosions, the hammering stopped. The entire battle had lasted about four hours, but to Smitty it seemed like several eternities.

The Seal‘s Escape

Finally, Smitty spoke quietly into the throat mike: “Control, tubes aft. All tubes reloaded.”

“Very well, tubes aft. Stand easy.”

The sub hunters had gone, and Seal swam silently out of the area, propelled at a slow but steady three knots. Eventually the order came to secure from depth charges and silent running. The boat surfaced, fresh air poured in, and the bunks were returned to their normal places in the torpedo rooms. Exhausted men fell into them.

Smitty took stock of himself. It had been his first combat, and he was surprised to find that he had been excited but not terribly frightened—he had been too busy to be really scared. He also noticed that he was more exhausted than he ever remembered being. As soon as a bunk came available, he slid into it, just a stiff mattress covered with green plastic, his nose only three inches from the oil pan under the 30-horsepower electric motor that powered the stern plates. Heedless of the motor’s noise, he fell asleep in seconds.

Several weeks later, in June 1943, after refitting and considerable additional training, Seal left Midway to begin her seventh war patrol. According to the secret orders in the sub’s safe, Seal was to patrol in Japanese waters off the home island of Honshu—a very dangerous place—some 3,000 miles from Midway.

Storm at Sea

After five days at sea, Seal ran into a typhoon, the Orient’s version of a hurricane. Plunging into waves taller than houses convinced the crew that this was no ordinary storm. The boat was rolling 30 degrees from side to side, and everything loose within the sub had to be lashed down or securely stowed. Sleeping men even had to be tied into their bunks to keep from being dumped onto the deck. Everyone except the saltiest of old salts got violently seasick. At the height of the storm, Smitty volunteered for a topside watch as starboard lookout. “I couldn’t sleep and I couldn’t eat,” he said. “Might as well do something useful.”

The storm was the most powerful, violent thing Ron Smith had ever experienced. The wind was blasting the rocking sub at speeds up to 100 miles an hour, and the rain, instead of coming from just one direction, seemed to be coming from all directions at once. Seal was battered from one wave to another like a shuttlecock. Smitty, on topside watch, fastened a lifeline around his waist, secured it to the railing, and held on.

“A swell would form like a hole in the ocean 50 to 70 feet deep,” Smitty related, “with a black wall on the other side just as high. Seal would fall into the hole like an airplane in a freefall dive, then slam into the wall of water on the opposite side, shuddering as she wallowed back up and over it.”

Most of the wave washed over the boat, and Smitty shut his eyes and held his breath, hanging on with all his might when he saw it starting to crest over him. Then down the black wave would crash, smashing into him like a giant wet fist, trying to rip him from the tenuous safety of the boat and throw him into the sea.

There was one redeeming feature to the storm: if any enemy ships were out their in the roiling sea, the Japanese sailors would be in the same stew—fighting Mother Nature instead of the Americans.

After enduring several hours of being banged around in the storm and soaked to the skin, Smitty was at last relieved and struggled to get below, where it was dry. He retreated to the mess hall that was pitching back and forth and grabbed a mug of hot coffee that kept sloshing all over him. He then dripped his way to the control room. “Why’re we riding this out on the surface, Chief?” he asked Red Servnac, an old salt and veteran submariner. “Why don’t we just submerge and get out of this shit?”

“Didn’t know it was going to be this bad,” Servnac answered. “It’d be hard to dive in this now. We’d probably take as much air into the dive tanks as water. Not sure we could dive.”

Lieutenant Jack Frost, the engineering and diving officer, leaning against the gyroscope table to keep his balance, joined the conversation. “It’s better we ride it out on the surface, Smith,” he said. “Seal can take it. She’s a tough girl.”

Still skeptical, Smitty nodded and headed back to the caboose—the aft torpedo room—stripped off his sopping clothes, wrung them out, and put them back on before sliding into a bunk and strapping himself in. At least my clothes got washed, he thought, sighing with resignation about the situation.

After three days, the storm moved on and Seal once again swam in calm seas, heading for Honshu.

Fate of the USS Runner

After a week––half of which had been spent struggling against the storm and the other half engaging in battle drills to sharpen the crew’s combat skills––Seal finally arrived off the northeast coast of Honshu, the enemy’s front yard. With daylight lasting 20 hours a day at this latitude, Dodge kept Seal submerged most of the time, coming up for only about four hours in the darkness to charge the batteries.

It was a risky thing to do, for if Seal were spotted by the enemy she would have to dive and get out of there fast––and who knew what would happen if the batteries didn’t get a full charge?

Being this close to Japan, the traffic was terrific. Ships went left and ships went right, but Dodge bided his time, staying low, refusing to shoot. Everybody wanted to know what the hell they were waiting for.

One day the dim thumping of depth charges detonating a long way off reverberated throughout the sub, but no one knew why. “Ask Control what’s going on,” one of the torpedomen directed Smitty, who was on the headphones.

“Control, tubes aft. We’re hearing explosions back here. What’s going on?” Smitty asked.

“Tube aft, Control,” said “Cowboy” Hendrix, a sailor manning the phones in the control room. “We hear it, too. Don’t know what it is, but it’s definitely not for us. Too far away.”

“Ask him if anyone else is close,” Big Ski told Smitty.

Cowboy reported that Mr. Greenup, the executive officer, thought that Runner was nearby, to the south of Seal.

The tempo of the explosions picked up, like the final minute of a Fourth of July fireworks show, but still at quite a distance.

“Sounds like they’re working someone over pretty good,” said a sailor named Lago. Men just stared at the bulkheads and listened.

At about 9 pm, the thumping stopped, and the crew in Seal relaxed a little. Then, about 45 minutes later, Lumpy Lehman came on over the circuit; he had picked up an emergency signal. “Sounds like the Runner. Weak signal, hard to read. Sounds like they are saying they’re stuck in the mud or something. Can’t make it out.”

Lieutenant Haines’s voice came on. “Sound, Control. Maybe they’ve run aground. Keep listening.”

“Sound, aye,” said Lehman.

The men of Seal were quiet. The signs were clear—Runner had probably gone down. A sister submarine was dying. Or dead. Seal was filled with a sobering silence. They knew that it could be their fate, too.

A Brilliant Maneuver

At 10 pm on July 7, 1943, Seal surfaced again in darkness to recharge her batteries. All four diesels ran at full power to squeeze as much juice as possible into the lead-acid cells during the short time available.

At 3:40 the next morning, radar picked up the blips of a large convoy streaming north at 12 knots: three big transports, five or six smaller ships, and a few escorts. The convoy was hugging the coastline, exposing only the starboard side and giving Seal little maneuvering room.

Dodge thought it was risky but worth a shot; he put Seal on a northerly course at flank speed on the surface to intercept the convoy. Throughout the boat, men practiced their procedures of preparing to engage. When Seal got to the ambush point, she went to battle stations submerged and dove to periscope depth. Target range, speed, and distance were fed into the TDC. Everything was ready for the attack.

Lumpy Lehman suddenly reported, “Small fast screws closing from port side.” It was a Japanese sub homing in for the kill!

“Drop her to 150 feet,” Dodge commanded. Lieutenant Frost ordered all ballast-tank vents opened, sending Seal on a steep plunge. The command had not come a moment too soon, as all hands on board heard the distinctive, high-pitched screeeeooooom sound of a torpedo ripping through the water just above them. Smitty nearly jumped out of his skin at the noise.

“Periscope depth,” ordered Dodge, and Seal rose at his command. They were still going to attack the convoy!

“Stand by, tubes forward,” said Haines.

“Tubes forward standing by, aye,” said Rick “Big Wop” Bonino, with a hint of glee in his voice.

Smitty listened intently on his headphones as Dodge maneuvered Seal into position for a shot from the bow tubes. In his mind’s eye, Smitty could see his counterparts in the forward torpedo room doing everything needed to prepare for the attack.

“Fire one,” said Dodge, and Seal lurched under the kick of compressed air. Two more torpedoes left the sub in quick succession. “All ahead full,” directed Dodge. “Tubes forward, start your reload. Take her down to 100 feet.”

“Tubes aft, stand by,” said Hanes. “Open doors five, six and seven.”

“We’re going under the son of a bitch!” exclaimed Big Ski.

“If those first three fish hit him, he’ll come down right on top of us!” yelled Lago.

“Knock off that shit, Lago,” shouted Woody. “The Old Man knows what he’s doing.” The torpedomen began cranking open the outer tube doors.

It was now clear to everyone: shoot from the bow tubes, go under the target, then hit him again from the other side with the stern tubes. It was a brilliant maneuver, one that, as far as Smitty knew, no one had ever tried before. But weren’t they too close to the shore? Wouldn’t Seal run aground once she got on the other side of the target ship?

“We’re at 365 Feet!”

There was no time to worry as Haines’s voice crackled in Smitty’s headphones. “Tubes aft, Control. Stand by to fire five.”

“Tubes aft standing by to fire five, aye,” said Smitty as he intently focused on the TDC box, waiting for the bugs to come into line.

Suddenly—Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Three shock waves smashed into and through Seal. The caboose was plunged into total darkness as the light bulbs blew out. It quickly became very cold and very wet as water began spraying from pipes burst by the force of the torque that had twisted the ship. Men were yelling, swearing, praying, giving commands, shouting warnings.

Instinctively Smitty reached out and grabbed anything he could find to steady himself and keep from being tossed around the blackened room with all its hard, protruding surfaces. He felt the boat tilt upward at a sickening angle. At that moment the dim emergency lighting came on.

“Holy Mother of God,” gasped Big Ski as he stared at the depth gauge. “We’re at 365 feet!” The old hull groaned under the weight of 200 pounds of pressure per square inch. Everyone knew that Seal’s maximum test depth was 90 feet shallower; she had never been this deep before.

Click … KaBLOOM!

“Rig for depth charge! Rig for silent running!” came the order from Control. Smitty, scared out of his wits, repeated it.

“A little late for that,” somebody wise-cracked as the aft torpedo crew dogged down the watertight door, closed the bulkhead flappers, and secured the outer tube doors.

Click … KaBLOOM!

“What the hell happened?” somebody demanded to know.

“The sons of bitches caught us with our pants down,” Woody replied.

Click … KaBLOOM!

Seal shuddered as though being beaten with a baseball bat the size of a smokestack.

“We’re getting gang-banged,” shouted Dead Eye as he hung onto a loading rack.

Water continued to spray into the compartment from ruptured lines. With the upward slant of the deck, the icy water was knee deep down near Smitty’s station and getting deeper.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Although the men of the Seal didn’t know it yet, seven Japanese destroyers had positioned themselves between the convoy and the coast, invisible to Seal’s periscope and radar. At the first salvo of torpedoes, the enemy tin cans had swung through the convoy, pinged Seal, and started dropping their deadly munitions. Seal had run into a captain—or seven of them—who could drop depth charges “down the hatch.”

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Sound and pressure waves reverberated through the hull, and Smitty was amazed that he could actually see the steel bulkheads bend and move with each shock as though the sub were made of aluminum foil.

The men in the caboose tried to climb higher, away from the rising water, but the deck, slick with an oily film, prevented traction. The water, only a couple of degrees above freezing, chilled the air and the men could see their breath clouds.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Damage Reports

Damage reports from the different sections of the sub were coming in thick and fast over Smitty’s headphones, and he relayed the depressing information to his mates: “Forward torpedo room flooding; a gasket on the sound head is leaking; control room is dry but the pump room is flooded almost to the control-room hatch; after-battery room has some water, still about eight inches from the batteries.”

This last bit of news was especially ominous, for if the water reached the batteries, it would combine with the acid to create chlorine gas and kill everyone on board.

“Forward engine room reports minor leaks, not much water in the bilges,” Smitty continued reporting to his mates. “After-engine room flooded to the decks.”

It was Smitty’s turn to report to Control: “Outer doors closed, water about halfway up the deck, stern depth gauges reading 365 feet.”

“Very well, tubes aft,” came the calm response from Control. Smitty wondered how Haines could be so unflappable at a time like this, but the officer’s calmness helped to settle Smitty’s nerves. Maybe things aren’t as bad as they seem, he said to himself.

“What time is it?” a torpedoman named “Hopalong” Cassedy asked Smitty, who moved so he could see the chronometer.

“Zero seven-twenty,” Smitty replied. It was July 9, 1943. He wondered if he would live to see July 10.

“It Don’t Get Closer Than That”

“It’s been less than an hour since the attack started,” Woody said quietly in disbelief. It seemed as if they had been under fire for hours. Somebody mentioned that the depth charging had ended about a half hour earlier. They were starting to breathe easier, but were still worried about water reaching the batteries.

“All compartments, we’re going to try to correct our trim,” Control said, but no sooner were the valves noisily opened than another rain of depth charges cascaded down.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

“The sound of a depth charge cannot be described,” Smitty later said. “There is no other sound like it. Worse than the loudest thunder, 10 times louder than a large bomb, a sound so powerful that it goes through the spectrum of physical sound that the ear can hear and turns into a pressure wave.”

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

“It don’t get no closer than that,” the crewman named Brown growled as his knuckles turned white from holding onto an I-beam.

The charges kept coming in a seemingly endless deluge. Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! There were so many explosions, the men began to think that the enemy destroyers were returning to port, reloading, and coming back to drop more. Maybe all of the depth charges in Japan were being used to sink Seal.

Smitty started to grow really scared. His fellow crew members were the best in the business, but they had no way to fight back, no shield to deflect the blasts, no magic wand to make the enemy disappear and the bombing stop.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

When, dear Lord, will it end? ran through each man’s mind. How much more of this shit do You expect us to take?

Lieutenant Frost, the diving officer, was unable to change Seal’s awkward angle by correcting her trim. Each time they tried pumping water from the tanks, the Japanese sonar men would hear the noise and more depth charges would come down. They definitely had Seal pinned to the mat and were not about to let her up.

Three more hours passed, but there was no cessation in the assault on nerves and eardrums.

“Sound, can you tell us anything?” Control asked Lumpy Lehman at one point.

“Control, I make seven destroyers and some smaller craft nearby, probably destroyer escorts.” This was the first time anyone had heard about the number of hunters who were up there. No wonder the cannonade never seemed to cease.

“Very well, Sound,” Control acknowledged quietly, again without emotion, almost as if he had just been given a weather report for fair skies and calm seas.

It was getting colder by the minute in the aft torpedo room. Is this my tomb? Is this where I’m going to die? Smitty thought. He wondered how his dad would take the news. And his girlfriend Shirley back in Hammond. They won’t even have a body to bury. The thought depressed him even further.

“Sounds like the Indians got our wagon train circled”

Lumpy Lehman gave his assessment of the situation: “Sounds like they’re circling us and takin’ turns runnin’ across the circle and droppin’ a load on us.”

Smitty repeated what he heard, and Brown tried to lighten the tension: “Sounds like the Indians got our wagon train circled.” The men in the caboose laughed a little harder than they might ordinarily have done. Then the room grew quiet again. Each man in the group would close his eyes and lower his head every once in a while. The others knew he was praying, as they all were.

Smitty issued his own silent prayer. Please, dear God, please help me, please help us. I don’t mind dying if it will help get this war over, but I don’t think it will. Please give me the strength to do whatever I have to do.

Lago tried to relieve the tense atmosphere with a dirty joke, but it fell flat.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Woody also made a contribution, but before he could get to the punch line, he was interrupted by Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Suddenly a new sound—a sharp, loud POING!—rang through the hull as though Seal had been turned into a large gong.

“Sonar,” said Dead Eye. “He’s pinging on us.”

“That son of a bitch really has us now,” offered Big Ski, standing up and facing the bulkhead. It was the first time Smitty had seen Big Ski scared. The destroyers had zeroed in on Seal with their active sonar and were echo-ranging, bouncing the signal off the massive steel hull of the helpless sub and calculating her position. It was the only sound that submariners dreaded more than the sound of depth charges. It meant the destroyers knew exactly where Seal was, as though she had a giant flashing neon target painted on her side.

An Underwater Picnic

A new sound now greeted the submariners’ vibrating ears: Pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. It sounded like a string of large, underwater firecrackers.

“Shit. Depth bombs,” Woody said.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Eight more depth charges went off, and a lot more bombs.

“They probably got an airfield near here,” said Hopalong.

“Yeah, and a goddamn bomb factory, too,” said Big Ski, shivering, “and we’re right at the end of the assembly line.”

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Big Wop Bonino, in the forward torpedo room, was keeping score of the number of charges dropped and periodically reported his count quietly over the circuit. “Two hundred and twelve,” came the latest total.

Somehow, incredibly, they were all still alive. Since their demise no longer seemed imminent, thoughts of living took over, especially thoughts of food.

“I’m starved,” said one.

“Me, too,” said another.

Suddenly the men started pulling cans of food out from secret storage places, such as from behind the spare torpedoes, and pooled their wares. There were several cans of Dole pineapples, some sardines, and a tin of soda crackers. The sailors broke out their knives and cut open the cans. “It would have made a nice picnic except for the freezing cold and the continuing explosions of the depth charges,” Smitty later said.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

“Boy, those bastards just ain’t givin’ up,” said Big Ski, his mouth stuffed with crackers.

Running Low on Oxygen and Time

The hours dragged by, but the Japanese destroyers refused to slacken their efforts to kill the picnickers. Strangely, it was becoming as routine as depth-charging could become. And, surprisingly, despite Seal’s odd upward angle, Dodge was managing to keep the submarine moving forward at reduced power, hoping to slip away from the enemy.

Damage reports came in from various parts of the sub. The pump room was flooded and out of commission, some vents were damaged, and engine mufflers had been blown away. Worse, the fuel tanks had been punctured and Seal was leaking diesel fuel; the oil would form a shiny rainbow on the ocean’s surface, making it very easy for enemy destroyers to track her movements.

A diminishing supply of oxygen was also becoming worrisome. Dodge ordered everyone to open five-gallon cans of a white powder—carbon dioxide absorbent—and spread it around to help preserve the oxygen. Cigarette breaks were cut down to five minutes every hour, but when the men lit up, they found it virtually impossible to keep the tobacco burning.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

Would it never cease?

Smitty slowly began to realize that their chances of making it out alive were diminishing by the minute. Not only was the oxygen running out and the water getting closer to the batteries, but the Japanese could continue to bomb and depth charge them from now until the end of time. After all, they were just off the coast of Japan. When a destroyer ran low on depth charges, it could just pull into the nearest port and reload. How stupid was Dodge for attempting this stunt? Smitty thought. How stupid was the Navy for sending them practically into the emperor’s bathtub?

Smitty was sitting on the inclined deck, his bare knees drawn up and his arms wrapped around them, his teeth chattering from the cold. How stupid was he for not bringing any warm clothes on this patrol?

Bitter thoughts ran through his head. Why did we have to get involved in this war, anyway? The Japs attacked us because we tried to keep them from getting the oil and rubber and steel they wanted. What business was that of ours? If they had done the same to us, wouldn’t we have attacked them first?

Smitty thought, Why should I have to die for something I didn’t start? After all, it doesn’t make any difference what kind of government you have as long as you have enough food, have a wife and kids, and are left alone. I bet the poor, dumb bastards in Japan and Germany feel the same way. I don’t mind dying if it would make a difference, but it won’t. Why are we humans so stupid? We’re all going to die, and it won’t make a damn it of difference in this war. Hell, we didn’t even sink the target!

Smitty continued with his black thoughts. And the Japanese continued to send their depth charges down.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

The seven sub hunters hung around all day, taking turns gleefully bombarding Seal, like bullies beating a puppy. The air in Seal was getting really foul. The batteries, too, were running out. Smitty didn’t know if there was even enough high-pressure air left to blow the ballast tanks and bring her to the surface. They were, Smitty knew, as good as dead. The destroyers just had to stay up there a few more hours and it would all be over. Maybe he should just close his eyes and give up.

Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM! Click … KaBLOOM!

“If We Die, We Die Fighting”

It was July 9, 1943. The chronometer read 2300 hours––11 pm. Seal had been submerged for 18 hours, and many of the men wondered if this would be the day of their death.

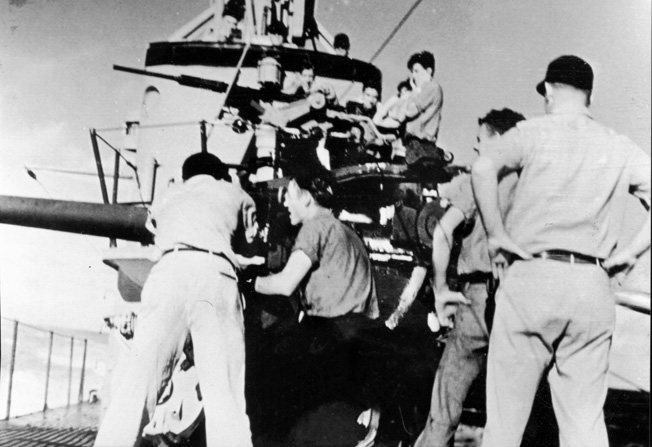

Lieutenant Commander Harry Benjamin Dodge had other ideas. To him, it was time to bring Seal to the surface and slug it out if need be. If he didn’t, he and his crew would certainly all have their names carved into a memorial slab somewhere. The chances of being able to outrun the enemy ships were slim to none, but they were better than lying 365 feet beneath the surface and waiting for the inevitability of asphyxiation.

Suddenly the order, “Battle-surface crew, report to the control room,” came over the headphones. Startled, Smitty repeated the command and stood up.

“What the hell is this?” grumbled one of the other sailors in the caboose, but he also stood up because he, too, was on the battle-surface crew. In fact, everyone in the aft torpedo room except Big Ski had some function on the battle-surface detail, and they all filed out.

Smitty was the last to leave the compartment and, as he did, he turned to Big Ski. Their eyes met. For a moment Smitty thought he might never see Big Ski again.

“You gonna be okay?” Smitty asked.

“It’s okay, Smitty,” Ski said, holding out his hand and shaking the youngster’s, almost as though he knew what Smitty was thinking. “Give ‘em hell, kid.”

The control room, illuminated only by red bulbs to preserve night vision, was already packed by everyone on the gun crews. Dodge climbed a couple of rungs on the conning tower ladder so everyone could see him. “I’m proud of all of you,” he said. “We’re not going to stay down here and die like rats. We’re going to wage this battle on the surface and if we die, we die fighting, like Americans. Bring her up, Lieutenant Frost.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” said the diving officer. The electric motors, nearly completely drained of their energy, strained weakly to push Seal upward. At a depth of 100 feet, Seal seemed to hang, unable to make the last few fathoms to the life-giving air above, ready to slip back down in a death dive. Then, without warning, she gave one last lunge, and the periscope broke through the waves, followed by the bridge and the conning tower.

No Destroyers in Sight

Dodge ordered the main induction valve opened so that it would draw air into the engines. “The huge engines pulled a vacuum in the boat that felt like it would suck your guts out through your nose,” Smitty said.

The diesels caught and roared to life. Dodge scrambled up the ladder, cracked open the hatch, and a blast of cool, fresh air, along with a small torrent of cold seawater, poured into the superheated interior, instantly turning the atmosphere inside the control room into a thick fog. Every man began rushing for the ladder, following their leader, spilling onto the deck, running for their guns, eager to hurt the enemy before they died.

Smitty slipped and slid across the dark, wet deck as he sprinted for his 20mm gun position aft of the conning tower. He opened the ammo locker and began retrieving shells as fast as he could, feeding them to the gunner, expecting that at any second now Japanese shells would rake Seal, for the destroyers had been up there all day, licking their collective chops, just waiting for Seal to surface.

The three-inch gun swung on its mount, the gunners straining their eyes to find targets in the pitch dark. The same for the 20s. Fingers tensed around triggers. It was now or never.

There was only one problem.

The seven Japanese destroyers were gone.

The men scanned this way and that, trying to pick out the enemy. But there was nothing, no one, not a sign of anything. The sea around them was black, vacant, empty.

The crew was happily perplexed. Perhaps the enemy had run out of ammo. Perhaps they had concluded that Seal was lying dead on the bottom of the ocean. Or perhaps they had just gotten bored and gone home. Whatever the reasons, the Japanese had vanished, leaving Seal totally and mysteriously alone beneath the stars.

Everyone was silent as they secured from battle stations, cleared the decks, and returned to the sub’s interior as Seal sped away.

They felt they had just experienced something that was beyond words, beyond comprehension.

Returning From the Silent Service

After this brush with death, Ron Smith returned to the States for a furlough while Seal was repaired and upgraded, during which time he met and married a young lady. Smitty was then ordered to report to a fully refitted Seal for more sea duty. But he was diagnosed with what is now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and did not return to combat. Instead, he was assigned as an instructor at Great Lakes Fleet Torpedo School at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago, and then to a naval ammunitions depot in central Indiana.

Smitty’s marriage failed, and then, with the war now over, Smitty was discharged and returned to civilian life in Hammond. There he met Georgianna Trembczynski in neighboring Calumet City, Illinois, and they were married in November 1946. He engaged in several careers, finally settling on the automotive industry; even though he swore a hatred for the Japanese, he eventually became the owner of a Toyota dealership. He lived in Austin, Texas, until his death in 2010.

After the war, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific, wrote, “During the dark, early months of World War II, it was only the tiny American submarine force that held off the Japanese Empire and enabled our fleets to replace their losses and repair their wounds. The spirit and courage of the Submarine Force shall never be forgotten.”

My friend Billie Davis Sullivan was on this boat from beginning to end. He was call Sully. He told me most of the stories in this saga, and more. Sully passed on the morning of his 94th birthday. He was well loved by all that knew him. I miss my friend. His best friends were called Moon and word used for a guy that was popular with the ladies. He was unaware that Seal sank a Japanese ship when they were run over and lost their main periscope.

I was just an eight years-old kid in the fall of ’45 when the submarine SS-183 and other surface ships visited our hometown in Camden, NJ. This was part of a (didn’t know it then) WWII Victory Tour. Got a never will be forgotten walkthru of the sub. Touched and felt everything within reach. Had to be dragged off the Seal, then on to a not as memorable tour of a destroyer. Thanks to all of those veterans, we are able to talk and write about it today.

The site-pier the Seal visited is now occupied by America’s Most Decorated Battleship, USS New Jersey (BB-62). Adjacent piers presently berth Cargo ships. I’ve made several attempts to pique the interests of responsible officials to remember and honor all the vessels in the 1945 Victory Tour, on any day worthy of choice. Unfortunately every effort to date has been unsuccessful. There’s still a few holidays left in life so just maybe… Semper Fi

GREAT ARTICLE. THANK YOU

[email protected]

Great story — I don’t know much of the details about Seal, so I may have to buy the book. Thank you for the heads-up!