By David Alan Johnson

John William O’Sullivan watched the Duke of Cumberland’s army as it stretched out in front of him, lined up in battle order on the northeastern side of Drummossie Moor, a mile or so from Culloden House. The army numbered about 14,000 men, but probably seemed even larger to O’Sullivan. He could see two rows of infantry, with cannon between the individual regiments and cavalry on each flank. Even in the midmorning rain, the red coats of the Duke’s men appeared vivid and intimidating. The swords of the officers glittered, and the muskets and spontoons of the infantry reflected the gray light. It was an inspiring sight—or a frightening one, depending on whether the person looking at all this power was a Jacobite or a Royalist.

To John O’Sullivan, the scene on the north side of the moor on the morning of April 16, 1746, was terrifying. O’Sullivan was the Quartermaster General of the Jacobite army. His own Jacobite force consisted of about 4,000 men, which meant that his army was outnumbered by more than three to one. O’Sullivan rode back to Culloden House to report what he had seen to the leader of the Jacobite cause, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, best remembered as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

A Battle 61 Years in the Making

The impending battle would begin in the early afternoon. Charles Edward Stuart would have agreed that it had actually begun 61 years before, in 1685, when Charles II died and his brother the Duke of York succeeded him as James II.

Charles was the grandson of James II and shared, among other things, his arrogance and his religion. James converted to Roman Catholicism in 1671 and behaved with the single-minded zeal of a convert. He seemed to go out of his way to alienate and offend as many of his subjects as possible. The vast majority of England was Protestant; only one in 400 was Catholic, according to Winston Churchill. The House of Commons tried to keep James from succeeding to the throne by passing the Exclusion Bill, but the bill was defeated in the House of Lords.

After succeeding his father as king, James dismissed Protestant government leaders and replaced them with Catholics. He also increased the number of Jesuit priests and advisers at his court and held Mass, which had been banned by law, openly. Irish soldiers and Catholic officers dominated the army. James was well aware that the vast majority of the English public, including the nobility, were outraged by his attempt to convert the country to Roman Catholicism, but he did not care about their opinion.

On June 10, 1688, James’s queen, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son, also to be christened James. To the public—as well as to the army, the Church of England, and Parliament—it seemed that a Roman Catholic succession was now inevitable if James remained king. To thwart such a succession, James’s son-in-law, Prince William of Orange, was invited to come from Holland, assume the throne, and in Winston Churchill’s words, “liberate England from the Papist reign” of King James. William was Dutch but, more important, he was Protestant and was married to Mary Stuart, the Protestant daughter of James. William accepted the invitation. He landed at Torbay in November 1688 to begin what became known as the “Glorious Revolution.”

James Receives a Cold Shoulder From the Army

James called for his commanders to rally around him to fight William and his followers. But his senior officers—including John Churchill, probably the ablest field commander of his time and ancestor of Sir Winston Churchill—refused to support him. Without the army behind him, James realized that his situation was desperate. He was all too aware of what happened to his father Charles I at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and his Roundheads. He had no desire to become the prisoner of William of Orange and his Protestants. James and his family fled England, arrived in France on Christmas Day 1688, and became refugees at the court of Louis XIV.

King Louis allowed James to set up a shadow court at St. Germain-en-Laye. He was hospitable enough to the deposed king, but his real reason for allowing James to set up his own court was to use him and his followers, who were known as Jacobites (from the Latin name for James, “Jacobus”) to further his own purposes—creating as much trouble as possible for King William and England. The French king financed the first Stuart restoration attempt a year and a half after James fled England. Louis provided 13,000 officers and men for a landing at Kinsale, Ireland, in a campaign that was to be led by James himself. King William landed with an army of his own in June 1690 and met James and his forces at the Battle of the Boyne on July 1. William routed James and his army. James returned to France to wait for the next chance.

Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Young Pretender

For James, that chance never came; he died in 1701. Subsequently, Louis announced that “James III” was his father’s rightful successor. However, the next French-backed attempt to return the Stuarts to the throne did not take place until 14 years later, in 1715. The campaign began well for the Jacobites, who landed in Scotland and captured Inverness, but soon afterward the Jacobite army was defeated and the rebellion collapsed. Reprisals against the Jacobite prisoners were brutal. Many of the captured rebels were sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. The lucky ones were beheaded.

Five years following this failed rebellion, James and Clementina, who was the youngest daughter of Prince Sobieski of Silesia, produced a son who was christened Charles Edward Louis Philip Casimir. Because his father was known as the Old Pretender (the Jacobites called him the Old Chevalier), Charles Edward Stuart was called the Young Pretender (or the Young Chevalier). His most popular nickname would be Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Charles may have been bonnie, but he was no intellectual. He had no interest in school or study, and was functionally illiterate. Throughout his life, he had to employ assistants to read and write for him. The letters that he attempted himself are filled with misspellings and show no knowledge of grammar. His father sent for the tutor of Louis XIV’s children, a Scottish Catholic named Andrew Ramsay, to try to refine Charles’s reading and writing skills. After several months of frustration, Ramsay gave up and returned to France. Charles’s lack of intellect went beyond his difficulty with reading and writing. He has been described as ”obtuse,” “opinionated,” and just plain stupid. One biographer diplomatically put it that “in intelligence he was less than gifted.” This deficiency would prove fatal for him and for the Jacobite cause.

As if to make up for his intellectual deficiencies, Charles Edward was gifted with good looks. He was tall and very handsome, with fair skin and reddish-blond hair. He was also well aware of his looks and was more than vain about his appearance. His wardrobe included laces, brightly colored jackets, jewelry, and expensive leather boots. Charles was not effeminate—he was also an outdoorsman and an enthusiastic hunter—just vain. He also liked to have his portrait painted. According to all contemporary reports, he certainly lived up to his nickname, “bonnie,” meaning handsome.

Charlie’s Brother Henry

Charles had a younger brother, Henry, who did not resemble him at all. Henry was much smaller than Charles, with an olive complexion, black hair, dark eyes, and a long, angular chin. On the other hand, he had a quick mind; he liked books and learning and had an aptitude for both. He would enter the Catholic Church and eventually become a Cardinal. Between the two brothers, Charles got most of the looks while Henry got all of the brains.

By the early part of 1745, James Stuart and his court in exile had moved to Rome—the Stuarts had actually been expelled from France by the Peace of Utrecht in 1715—Louis XV was king of France, George II was king of Great Britain, and Charles Edward Stuart was 24 years old.

In spite of the Utrecht treaty, Louis secretly asked Charles to come to Paris. Louis was preparing a campaign of retaliation against George II, who had sent troops to support the Austrians against the French in the Battle of Dettingen in June 1743. The Austrians and their allies won the battle. Now Louis wanted to get even and he needed Charles.

The Campaign of the 45

Charles immediately thought that Louis intended to finance an expedition to restore his father to the throne. But Louis had no such thought in mind. All he wanted to do was divert George from sending troops to Flanders in the ongoing war between England and France and, if possible, to force him into withdrawing some of the troops he had already sent to the Continent to suppress a rebellion in Britain. Louis did not plan to help either Charles or his father. He wanted to use them to help him accomplish his own objectives.

Charles was certainly no match for Louis in either intellect or deceit. According to British historians Peter Young and Brigadier John Adair, Charles was “an arrogant and stupid young man whose chief assets were a strong constitution and almost incurable optimism.” He had no idea what Louis had in mind for him, and believed what he wanted to believe. In Paris, Charles was told he would be sent to Scotland to raise an army, and was promised money and troops to support his campaign. Charles was elated, and immediately began to communicate with Jacobite contacts in Scotland—he was coming to put the Stuarts back on the throne, he said, and would have the backing of King Louis. The offensive about to be launched by Charles and his followers would become known as “the campaign of the ’45” or, most frequently, “the ’45.”

Charles sailed from Belle Ile, off the south coast of Brittany in the Bay of Biscay, aboard the French privateer Du Teillay. He landed on the island of Eriskay, in the Hebrides, on July 25, 1745. Seven men came with him, along with several French artillery pieces and several hundred muskets and broadswords. Eriskay was the home of the clan MacDonald. When he came ashore, Charles was disguised as a monk, had several days of scraggly beard, and was covered with dirt. He looked like anything but the grandson of James II. The head of the MacDonald clan stared quite openly at Charles, not knowing what to make of him.

From Eriskay, the Du Teillay took Charles across to the mainland of Scotland. He landed at Loch nam Uamh and began his campaign to recruit men from the Highland clans for his Jacobite army. In the Catholic regions, he was given a great deal of assistance from the local parish priests, who became his most energetic recruiting officers. Some of the clans refused to join Charles, but any number of them did. The Camerons sent 700 men, and made up the main part of the Jacobite force when Charles raised his Royal Standard at Glenfinnan on August 19. At that point, he had a thousand men and a statement to deliver—he had come in the name of James III to put the Stuarts back on the throne.

The 10-Minute Battle of Prestonpans

The Jacobites moved south in very good order for the next several weeks, trying to recruit more men along the way. The army encountered no real resistance. Several local militia groups were in the area of the advancing Jacobites, but the militias were much smaller in size and dispersed when the advancing army moved into their area. On September 15, Charles and his Jacobites entered Edinburgh. One of the city’s four gates was opened to admit a carriage, and a group of Camerons rushed the gate and pushed its way into the city. The regular garrison retreated to Edinburgh Castle without offering any resistance at all.

During the first few days that the Jacobites were in Edinburgh, Lord George Murray did his best to organize the men into a more efficient army. But four days after entering the city, word was received that a government force under Sir John Cope had landed and was on the way to stop the Jacobites. Lord George took the army, such as it was, to meet Cope’s force. At dawn on September 21, he led the Jacobites against Cope’s undertrained men at Prestonpans.

The Highland clans charged at the government troops, whooping and screaming and waving their three-foot-long broadswords, which panicked the enemy. The Highlanders fired one round from their muskets and threw them aside, preferring to use their broadswords on the already demoralized opponents. Cope’s government troops took one look at the charging Jacobites and ran. The Battle of Prestonpans was over in about 10 minutes. As it was, Lord George thought that the battle had been too easy and that it had given Charles an inflated idea of his army’s abilities. George knew the limitations of his army, and also had a fair idea of Charles’s and his own limitations.

William “The Butcher” Augustus

When word reached London of Prestonpans and the rout of Cope’s force, the general reaction was alarm. No one had any idea that the government troops had been young and undertrained; they only knew that a rebel force was coming south from Scotland and had already brushed aside an army that had been sent to stop them. King George was concerned enough to meet with Parliament and to ask for immediate assistance to put down the Jacobite rebellion in Scotland. On October 19, an army of infantry and artillery arrived from Flanders under the command of William, Duke of Cumberland, the king’s third son.

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, was known as “Billy the martial boy’” by his friends, and as “the butcher” and a few other less than flattering names by his enemies. He was a big man—his enemies would have said “fat”—weighing about 250 pounds. Cumberland had a reputation for being a strict disciplinarian, but was generally respected by his men—he was too distant to have been liked. In addition to being the third son of George II, he was also the younger cousin (by four months) of Charles Edward Stuart.

While Cumberland organized his troops before beginning his march to the north, Charles prepared to move south into England. Charles had convinced himself that he would be able to recruit thousands to his cause after he crossed the border, and that England was just waiting for the chance to overthrow King George and the House of Hanover in favor of James III. Actually, most of England was enjoying prosperity under George and had no desire to replace him with the Stuarts. Also, most of the English public distrusted Catholics and hated the French. They certainly had no use for a Catholic pretender attempting to depose George with French help. A popular Jacobite uprising was only a figment of Charles’s imagination.

The Jacobite army, about 5,000 men, crossed into England on October 31, both to recruit more men and to march against London. But Charles’s vision of thousands of men flocking to his standard was only a pipe dream, as he soon found out. Except for about 200 volunteers from the Manchester area, which would be known as the Manchester Regiment, there were no recruits to speak of. The march south cost Charles some of his Highlanders, who had no desire to invade England and risk losing their property, and possibly their lives, to further Charles’s ambitions. These men deserted the Jacobite army and returned to Scotland.

The Jacobites Return to Scotland

Lord George Murray, Charles’s most able commander in spite of his limited military experience, argued that the Jacobite army had absolutely no chance of reaching London, and should return to Scotland. The reasons he cited were lack of popular support in England and the fact that an army commanded by the Duke of Cumberland was on its way north. Charles argued back, shouting that he was being betrayed. But Lord George was the stronger of the two, and won out. The Jacobites began moving north and entered Scotland again on December 20.

Since he had marched out of Scotland less than two months earlier, Scotland’s attitude toward Charles had changed. While he had been wasting his time trying to recruit volunteers in England, much of Charles’s support in Scotland had disappeared. Edinburgh had been re-taken by a force from England, and much of southern Scotland was now anti-Charles where it had been mainly neutral before. Also, Charles received word that an English army under General Henry Hawley was heading north to intercept the Jacobites.

Charles wanted to wait for the enemy to come to him and to fight a defensive battle. But Lord George did not agree. The Highlanders were used to going on the attack, he argued, and the best and most effective course would be to confront the enemy, not to wait for him to attack. Charles grudgingly agreed to Lord George’s suggestion, and the army began to move toward General Hawley and his troops. The two forces met at Falkirk on January 17, 1746.

The Highland units were carefully lined up by Lord George at the top of a hill with the wind at their back. The Hanoverians charged up the hill into the wind and the rain. Lord George shouted at his men to hold their fire until the enemy was about 30 feet away, and the men did as they had been ordered—the Jacobite volley blasted the first rank of the red-coated soldiers. That was the last order the Highlanders obeyed that day. In spite of Lord George’s direction, the troops did what they had done at Prestonpans: They threw their muskets aside and ran, screaming, at the enemy and waving their broadswords. The Hanoverians fired as well and charged with their bayonets. But the Jacobites deflected the bayonet thrusts with their shields and chopped at the enemy with their broadswords. Lord George tried to make the advance as orderly as possible, but his troops were no longer listening. It did not matter, at least not at that stage. In the face of a howling line of Highlanders thrusting and chopping at them with swords, General Hawley’s troops broke and ran.

The Highlanders Win Out at Falkirk

This time the battle lasted 20 minutes. The Jacobites lost about 50 men, while Hawley’s losses were about eight times that number, including many officers. General Hawley, who has been described as “a foul mouthed and brutal old man,” was outraged by the conduct of his troops. After he rounded up the scattered units, Hawley hanged 31 of his men and had another 32 shot for cowardice and desertion.

After having routed an enemy army for the second time, Charles and his Jacobites garrisoned themselves at Falkirk for the next few weeks. The original intent was to stay a much longer time, but supplies began running low and the army’s store of gunpowder, which was kept in a church, blew up. The Jacobites left Falkirk on February 1 and retreated northward, while Cumberland’s army also moved steadily to the north to meet them. Charles and his troops reached Inverness on February 18.

The locals in the villages they passed through on their way north were definitely not sympathetic toward Charles or the Jacobites. They sold food to the army when the soldiers had money to pay for it, but offered no comfort or encouragement. Cumberland and his army were on the way, and everyone knew it as well as Charles and Lord George did. No one wanted to risk reprisals at the hands of the Hanoverian troops.

Waiting It Out in Elgin: Sending For Aid In France

From Inverness, Charles next traveled to Elgin, about 35 miles to the east along the coast. From there, Charles waited for reinforcements from France. Charles had high hopes for assistance from the French, but so far Louis XV had not sent very much help. He did send 120 men from the FitzJames regiment, but never intended to deliver a major force. Cumberland had taken a major part of the British army out of Flanders, and Louis had already accomplished what he set out to do: distract the English with a rebellion close to home. Charles waited in vain for any more support from Louis.

Charles and the Jacobites spent most of March at Elgin. Besides waiting for French troops that would never arrive, Charles also suffered from a fever and a skin disorder, caused by malnutrition, which kept him immobile. By the beginning of April, Charles had recovered from his illnesses and the weather had become more civil. The Jacobites moved to Culloden House, about six miles east of Inverness. Culloden House was the residence of Duncan Forbes, Lord President of the Scottish Court of Sessions. Charles took great relish in looting the cellar of the Lord President of its stock of wine and Madeira.

While Charles was at the Lord President’s house, the Duke of Cumberland continued his progress northward. After Prestonpans and Falkirk, he had been given command of all Hanoverian troops in Scotland—he might not have been a brilliant commander, but he had to represent an improvement over either Cope or Hawley. The army, complete with artillery, crossed the River Spey on April 12. Two days later, it reached the River Nairn, about eight miles east of Culloden and the Jacobite army.

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, turned 25 on April 15. His troops celebrated the event with beef, most of which had belonged to the Jacobites until they abandoned the herd on their retreat northward from England, cheese, bread, and local beer. (The officers had brandy.) When Charles received word of the celebration, he hoped that Cumberland and his army would be so drunk for the next day or so that they would not be able to fight. Charles clearly did not know his enemy.

Cumberland Studies Hawley’s Missteps

In the weeks since Falkirk, Cumberland had studied the problems that General Hawley had faced and took steps to counter them. The infantrymen were trained to stand their ground and fire in volleys when the Jacobites made one of their howling charges at the line. The Duke of Cumberland issued the following instructions to his troops: When the Highlanders charged and were within 10 to 12 paces, the red-coated ranks would be ordered to “Make Ready” and “Present.” With those commands, the men in the third (rear) rank were to cock and aim their muskets. When the kilted men came within point-blank range, still howling, the order would be given to fire. As soon as the third rank fired, the second rank would be ordered to fire, followed immediately by the front rank. By firing at such close range, there would not be time to reload, only to prepare to fight with the bayonet.

There is also some evidence that the British soldiers were given further training in bayonet drill. When the Highlanders’ charge carried to the British line they typically used their shields to push aside the bayonets of the redcoats, slashing down with their swords. At the moment the charging enemy raised his right arm to strike with his broadsword, Cumberland’s soldiers were taught to thrust their bayonet at the exposed underarm of the Jacobite to their right. This represented a significant tactical change, because it meant that each soldier would now protect the man to his right instead of himself. Between concentrated musket fire and the new bayonet drill, Cumberland hoped that the Jacobites’ charge would be turned against them.

The Jacobites attempted a night attack on Cumberland’s camp on April 15/16, hoping to surprise the men after their celebration the day before. But the plan was not very well thought out. The Jacobites became separated in the dark and never did reach Cumberland’s camp. After several hours of frustration, the planned raid was finally called off and the men retreated to Culloden.

Waking To The Sound of Cannon Fire

The Jacobites finally reached Culloden at about 6 am on April 16 “sullen and dejected,” having gone the entire night without sleep. O’Sullivan was so tired and hungry that he actually fainted. Many of the troops lay down and fell into a coma—they were beyond being just tired, they were drained and exhausted. For the past several days, the Jacobite army had been reduced to a diet of flour and water biscuits. Some of the men were suffering from severe malnutrition, which added to their fatigue. The commissariat kept insisting that supplies would be arriving shortly, but nothing ever happened. Charles later said that he sent some of the FitzJames horse to Inverness to buy meal for making oat biscuits. Charles himself “reposed with great difficulty having got some bread and whiskie.” The whisky might help to explain some of his actions later in the morning.

A few hours later, those who were awake heard cannon fire in the distance and the skirl of Cumberland’s pipers. (Cumberland had some Highlanders as well, including members of Clan Campbell.) At about 11 o’clock, O’Sullivan was able to rouse himself and investigate the activity on the other side of Drummossie Moor. After watching Cumberland’s army form into lines and ranks on the northeast side of the moor, and being all too aware of the condition of the Jacobites, O’Sullivan made plans for a retreat from Culloden. He ordered carts to be burned on the bridge over the River Nairn to prevent the enemy from following. The army was in no shape to fight, at least not on that day. A retreat was the only sane course of action.

But Charles would not hear of a retreat. With “whisky breath,” Charles somewhat inarticulately announced his determination to fight. He had taken command of the army himself, and had appointed O’Sullivan as his deputy. Lord George did not give his opinion, one way or the other, but it is unlikely that Charles would have listened to him or anyone else. It might have been because of his “incurable optimism,” but his decision to stand and fight was more likely due to his lack of mental potency and the effects of the whisky.

George Chooses Drummossie Moor To Make a Stand

Lord George did, however, offer his opinion on the choice of Drummossie Moor as a field of battle. The ground was not suitable for the Jacobites, he said, but it certainly did favor Cumberland and his forces. The flat landscape, with no hills or ridges between their front rank and the enemy, would give Cumberland’s gunners a clear field of fire. He begged Charles to consider a site on the other side of the River Nairn, which had hills and bogs and would offer more protection from the enemy’s artillery, but Charles flatly refused. He was in command, and O’Sullivan was his deputy commander. O’Sullivan had no complaints regarding the moor, and Charles saw no reason to overrule his deputy. He “distrusted his ablest general, Lord George Murray,” wrote historians Young and Adair, and “chose to lean on his hare-brained Quartermaster General, John William O’Sullivan.” Perhaps it was because he and O’Sullivan had the same type of intellect.

John William O’Sullivan was an Irish Jacobite with even less military experience than Lord George Murray. In spite of this, Charles gave a great deal of responsibility to O’Sullivan, and put a considerable amount of trust in him. This faith and trust seemed to have been based on the fact that O’Sullivan never contradicted Charles, something that Lord George often did.

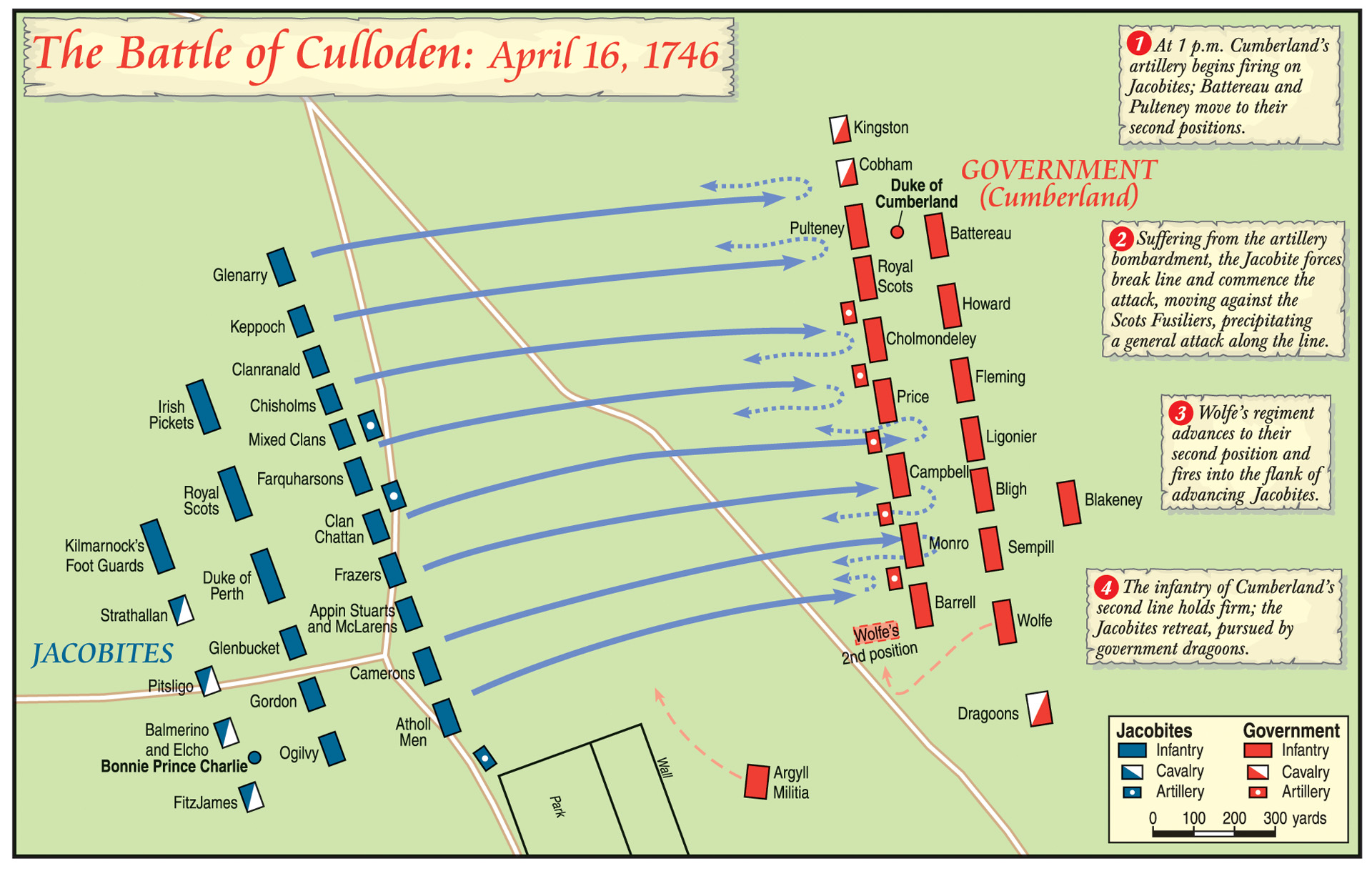

By one o’clock, Lord George and his officers had formed the Jacobite forces into three lines on the southwestern side of Drummossie Moor. In the front line were the Atholl Men, the Camerons, the Appin Stuarts, the Frazers, Clan Chattan, the Farquharsons, Mixed Clans, Roy Stewart’s men, and the MacDonalds. The second line consisted of Lord Oglivy’s Regiment, Lord Lewis Gordon’s Regiment, the Glenbucket Regiment, the Duke of Perth’s Regiment, the Royal Scots, the Irish Pickets, and FitzJames’ Horse. The third line was dismounted cavalry and Lord Strathallan’s regiment. Prince Charles and his lifeguards were situated at the rear. When they had formed up, Cumberland’s three-pounder battalion guns, along with some others to the rear and the left, began firing at them.

“A Continual Noise Like Ten Iron Doors Clanging”

Cumberland’s gun crews had been well drilled in the loading and swabbing out of a field artillery piece. First, a pound and a half of powder was rammed down the barrel, which was over three feet long, followed by a three-pound iron shot. A charge of powder was then poured into the touch hole, and the gunner set the charge off. As soon as the gun fired, with a booming crack, the recoil pushed it backward several feet. The crew wheeled it back into place, swabbed out the barrel, and began the process all over again.

Each battery fired at will, so the effect was not of a roaring volley but “a continual noise like ten iron doors clanging, one after the other.” The iron shot bounced toward the Jacobite lines, or arced overhead to strike men in the second or third lines.

One of the three-pound shot narrowly missed Charles, who was on horseback at the rear. The shot fell close enough to wound his horse, forcing Charles to take another. His groom was killed by another cannonball, which literally knocked his head off and splattered Charles with some of his blood. Cumberland’s gunners obviously had the range, and Charles was escorted away, taking his standard with him.

The iron cannonballs bounced toward the Jacobite lines with misleading slowness, and looked no more harmful than a rock skipping over the surface of a mill pond. But if one of them hit a man, it could take an arm or a leg right off, or disembowel anyone who was hit in the abdomen. Cumberland’s artillery was inflicting terrible damage on the Jacobite ranks. Officers shouted “Close up! Close up!” but as the gaps were closed, the round shot continued to kill and maim the Highlanders.

The Jacobite artillery fired back, four guns on the flanks and four in the center. The gunners seemed to be deliberately shooting over the heads of Cumberland’s ranks, trying to kill Cumberland himself. Because the enemy commander did not stay in one place very long, the Jacobites had no luck in hitting their target. Cumberland’s gunners were having their effect on the rebel artillery, as well as on the ranks of infantry. Nine minutes after the first Jacobite gun opened fire, the gunners stopped their largely ineffective barrage.

Weather Takes Its Toll Along With the Fighting

Along with the cannon fire, the weather was also taking its toll on the Jacobites. They had the wind at their backs at Falkirk, but here they had the wind and the rain in their faces. The wind also blew the smoke from the enemy’s cannon at them, which burned their lungs and hampered their vision. Cumberland was well pleased with his artillery, and with the effect it was having on the Jacobite ranks. “The cannon gave our men infinite spirits,” said a surgeon with one of Cumberland’s regiments. “The wind drove the smoke into the teeth of the enemy; their batteries were silenced … The thunder of our cannon was perpetual.”

Charles’s activities during the course of the battle are open to speculation. Some accounts that were written for his father state that he “rode up and down the ranks, spurring his men on.” He most certainly did not do this. There is evidence that he left the battle soon after he changed horses, and that Lord Elchro called him “a damned cowardly Italian.” He certainly did nothing at all during the first 20 to 30 minutes of the battle, while Cumberland’s guns were slaughtering his men. The Jacobite ranks waited for the order to advance, but it did not come. Charles wanted full command of the Jacobite forces, but now that he had it he did not know what to do with it.

This scene was a far cry from Prestonpans or Falkirk where the Highlanders took the initiative and charged the enemy with their broadswords. Now they waited for the order to advance so that they could use their swords on Cumberland’s men. The Highlanders pleaded with their leaders “as children to a father,” asking for the order that would allow them to move forward.

Some accounts say that Charles finally gave the order to attack by way of an aide, but that the aide was killed by a cannonball before delivering the order. Others insist that it was Lord George who gave the order. The Jacobites finally began their advance after about half an hour of cannon fire. The rain had stopped by this time, but the men could not see the enemy because of the cannon smoke. The Highlanders ran forward with the others of their clan—the Mackintoshes, the MacBeans, the Chattans—shouting, screaming, and waving their swords above their heads.

The Jacobites Advance

Cumberland’s gunners could not see any better than the Jacobites, but they could hear the enemy coming, even above their own cannon fire. The Highlanders’ shouting and their bagpipes’ skirrling carried forward to the English lines—and the gunners changed from round shot to grape. Grapeshot came in a paper cartridge that held the powder charge as well as lead balls, nails, and pieces of iron. The gunners rammed the entire cartridge down the cannon barrel, pierced it through the touch hole, and poured a small charge of powder into the aperture. Grapeshot turned the cannon into a gigantic shotgun. One of the officers referred to the grape canisters as “partridge shot,” recalling the ammunition he used when hunting game birds.

The Jacobites ran right at the enemy lines in three wedge-shaped formations, shouting unintelligible sounds and holding their broadswords above their heads. Halfway across the field, the Camerons and Stewarts collided with the Chattan clan, which slowed the charge. When Cumberland’s gunners opened fire with grapeshot, the charge was slowed still further. The small metal shot and bits of iron whistled through the air and mangled whatever they hit. It was not unusual for a single canister of grape to knock 10 men to the ground, wounding or killing every one of them.

To an Englishman of the 18th century and to most lowland Scots, the Highlands of Scotland were “a remote and unpleasant region peopled by barbarians who spoke an obscure tongue, who dressed in skins or bolts of parti-coloured cloth, and who equated honour with cattle stealing and murder,” according to historian John Prebble. In other words, Cumberland’s troops considered the Jacobites who were now bearing down on them to be less than human, and intended to show them no mercy. The Highlanders held just about the same opinion of their enemy and intended to show them the same degree of clemency.

At Prestonpans and Falkirk, the Jacobites fired one round from their muskets and ran at the enemy with their broadswords. But on Drummossie Moor they threw away their muskets before firing them, which is probably an indication of the frustration they felt after standing up to a half-hour of artillery fire. When a breeze dispersed some of the smoke, men on the Hanoverian right caught their first glimpse of the Jacobites as they charged. One of the soldiers wrote to his wife, “They came running upon our front like a troop of hungry wolves.”

The Rolling Thunder of Orchestrated Small Arms Fire

Cumberland had seven regiments in his front line: Pulteney’s Regiment; the Royal Scots; Cholmondeley’s Regiment; Price’s Regiment; the Royal Scots Fusiliers; Munro’s Regiment, and Barrell’s Regiment. Wolfe’s Regiment and the Campbells were at right angles to Barrell’s unit. In the second line were Battereau’s Regiment, Howard’s Regiment, Fleming’s, Bligh’s, Sempill’s, and Conway’s. Behind the two lines, in reserve, was Blakeney’s Regiment. Cavalry units were positioned at the flanks of the front line, and the artillery was placed between the front-line regiments.

Before the Highlanders could get within striking distance, the red-coated ranks were ordered to “Make Ready.” At that command, the men in the first rank put their muskets up to their shoulders. When the kilted men came within range, still howling, the order was given to fire.

The first rank fired and immediately began to reload; the second rank was then ordered to fire. As soon as the second rank fired they also began to reload, and then the third rank fired at the enemy. By that time the first rank had reloaded and was ready to fire again—it took about 20 seconds to load, prime, and cock a British army musket—and the process was repeated. An eyewitness said that “the fire of small arms began from right to left … which for two minutes was like one continued thunder equalling the noise of the loudest clap.” The soldiers opened their powder cartridges with their teeth, and their faces were black from the gunpowder.

Clan Chattan had 21 officers leading them in their charge. By the time they came within 20 yards of Cumberland’s infantry, all but three of them had been killed. Some of the Highlanders did manage to push their way through the front line, but they were bayoneted by the men of Fleming’s, Bligh’s, and Howard’s Regiments in the second line. “The brunt of the battle fell on Clan Chattan,” wrote one observer. Some of them just stood still in front of the redcoats—they would not advance into the musket fire and grapeshot, but were too proud to retreat. Since they had thrown away their muskets, they picked up rocks and threw them at the front ranks.

“The Highlanders Fought Like Furies and Barrell’s Behaved Like So Many Heroes”

Farther along the line, the men of Barrell’s and Munro’s Regiments were being charged by the right wing of the Jacobites: The Atholls, Camerons, and Stewarts of Appin. Cumberland’s men held their fire until the enemy was only 20 yards away, which allowed for only one volley from each rank. Barrell’s men were veterans, and were one of the few regiments at Falkirk that had not been unnerved by the attacking Highlanders. They held their ground here as well and were said to have been the coolest regiment along the line that day.

Wolfe’s regiment was situated at a right angle to Barrell’s and fired into the right flank of the Atholl Men. Thirty-two of the officers were killed in the attack, along with many of the men. But the Highlanders kept running forward, waving their swords in the air. Lord George Murray was with them, shouting “Claymore!” and brandishing his own sword. His horse took him right past the battalion cannon and to the rear of Cumberland’s army. By this time, his wig had been blown off, his sword was broken, and his coat was torn by bayonets and musket balls. The cannon and musket fire had panicked his horse, so he dismounted and began running back toward his own lines, desperate to send reinforcements for the attacking Highlanders.

The Camerons and Appin Stewarts had finally reached Cumberland’s front line, climbing over their own dead, and began chopping with their swords. The men of Barrell’s Regiment defended themselves with their muskets, and the clang of sword on musket barrel carried over the screaming and shouting. Barrell’s men remembered their bayonet drill, and gave as well as they got. The last thing that many of the Highlanders felt was the chilling surprise of unexpected death—a bayonet thrust from the red-coated soldier on his right instead of from the man directly in front of him.

Under the weight of the attack, Barrell’s Regiment fell back, and the Highlanders rushed through their line. “The Highlanders fought like furies and Barrell’s behaved like so many heroes,” said one of Cumberland’s men. The men of Barrell’s and Munro’s Regiments had hands and arms hacked off by broadswords, and the Camerons and Stewarts were bayoneted from all sides. But the men of Bligh’s and Sempill’s Regiments moved in from the second line to meet the Highlanders with their own bayonets. (Sempill’s men were lowland Scots.) Barrell’s and Munro’s turned around and joined the two incoming regiments. The Highlanders stabbed with their dirks (daggers) when there was not enough room to swing their swords, and the English and lowland Scots lunged with their bayonets. “Not a bayonet but was bent or bloody and stained with blood to the muzzles of their muskets,” wrote one of Barrell’s officers.

The Rifle Wins Out Over the Claymore

The Highlanders had finally met their match. This time the redcoats did not run and the clans discovered, as John Prebble put it, that “the claymores [broadswords] could make no impression against the bayonet charged breast high.” Cumberland’s training in bayonet drill and discipline was paying off for the Hanover regiments. Bodies of the kilted Jacobites lay three deep in some places, and the red-coated enemy kept on stabbing and thrusting. Blood formed in pools on the marshy ground.

Of the 300 or so Appin Stewarts who had charged the enemy, 92 had been killed and more than 60 were wounded, some fatally. One by one, the survivors of the attack began to withdraw. Lord George Murray, carrying a new broadsword, arrived with reinforcements—Glenbucket’s Regiment from the Jacobite second line—but by this time he was too late. The men were not able to advance through the retreating Appins and Camerons.

The battle was not over yet. Roy Stewart and the MacDonalds attacked the right of Cumberland’s line—just as the other Jacobite units had done, screeching and shouting and with swords held high. The men of Pulteney’s Regiment and the Royal Scots began firing in volleys by rank. But the Jacobites did not continue with their attack. Instead, they stopped about 100 yards short of the front rank, firing their pistols and waving their swords, “snarling at the infantry like animals encaged.” This was an attempt to lure the redcoats out of their lines, where they could be hacked to death individually. But the discipline of the red ranks held and Cumberland’s men continued their measured fire, which “chopped down the MacDonalds by scores.”

Their plan had not worked. The redcoats had not fallen into the trap, and the disciplined musket fire was slaughtering the Jacobites. The Highlanders began to withdraw. Some began to walk toward their own lines in an orderly manner, but the retreat soon became a rout. “What a spectacle of horror!” wrote an eyewitness. “The same Highlanders who advanced to the charge like lions, with bold and determined countenance, were in an instant seen flying like trembling cowards in great disorder.”

Conflicting Orders from Prince Charlie

When the retreating Highlanders were out of musket range, the artillery once again began shooting. The gunners no longer had to worry about hitting their own men, and fired grapeshot at the demoralized Jacobites. Non-commissioned officers shouted “Rest on your arms” to their men; the enemy was now beyond the reach of their muskets. Lord George knew that he had lost, but stood his ground and watched what was left of the Highland regiments move toward the rear.

By this time, Charles had been gone from the field of battle for some time. He rode to Gortuleg (now Gorthlick), about 20 miles away from Culloden, where he wrote two contradictory orders. Charles told Lord George to wait for him at Ruthven, and also ordered Cluny MacPherson to take his clan to Fort Augustus and meet him there. Actually, he had no intention of setting foot in either place. He had hopes that French ships were waiting for him off the western coast of the Scottish mainland, and wanted Lord George, the MacPhersons, and any other Highland clan in the area to cover for him while he made his escape. Charles believed that the Highlanders would try to collect the £30,000 that had been put on his head, and he knew all too well that Cumberland would kill him on the spot if he were captured. There is no evidence that anyone ever made any attempt to collect any of the reward money. But because Charles had very little honor himself, he could not conceive of it in anyone else.

On Drummossie Moor, the artillery stopped firing and the cavalry and infantry began to advance. General Henry Hawley, who had lost to the Jacobites at Falkirk, commanded the cavalry at Culloden. He encouraged both the cavalry and foot soldiers to kill any Jacobite they found that was still alive, and to bayonet any man they suspected might still be living. As far as most of Cumberland’s troops were concerned, the Jacobites were “traitorous rebels and papists, most likely to boot” and deserved anything they got, including slaughter. The dragoons stabbed and slashed at the wounded, and the infantry bayoneted anyone who was still moving. “Pillage, rape and murder were the order of the day,” Prebble wrote in Culloden, “the innocent suffering with the guilty.”

The battle had lasted just over an hour. Losses among Charles Edward Stuart’s followers numbered at least 1,200. Some reports give the number at 2,000, which was about half of the Jacobite force. Cumberland’s losses are officially given at 50 killed, 259 wounded, and one missing. Barrell’s Regiment suffered the worst—17 killed and 108 wounded out of a unit of 438 men.

Cumberland Becomes the Hero of the Hour

Shortly after the battle, the Duke of Cumberland received word that the Belgian cities of Hainault and Tournai were under attack by French troops and were in danger of being captured. He made plans to return to the Continent as soon as possible, but the French took both cities before he could leave Britain. King Louis had taken two cities of vital strategic importance from the British, largely because Cumberland and his army had been withdrawn from Belgium to fight in Scotland. Louis’s very limited support of Charles had certainly served its purpose.

Because of the battle at Culloden, Cumberland was the hero of the hour. England was almost wild with relief that the Jacobite threat was over, and could not do enough for the duke to show its appreciation. His father, George II, gave him £1,000—a small fortune at the time. George Frederick Handel composed The Conquering Hero in Cumberland’s honor. A flower, Sweet William, was named after him. (The Scots named a weed after him: Stinking Billy.) He was the toast of London, and every move he made became a headline in the press. But Cumberland’s military career had reached its high-water mark. After Culloden, he would be best known as the founder of the Ascot racing meet.

Charles Edward Stuart wandered across Scotland until September, when he escaped to France. Both O’Sullivan and Lord George also escaped. But the Highland clansmen whom Charles left behind were not as lucky. Those who were suspected of helping or supporting the Jacobites were killed or imprisoned or had their houses burned and their cattle driven off. Once again, the innocent were punished along with the guilty—many of those who lost their land and their lives had no ties at all with the Jacobites. Charles would live on the Continent, mostly in France and Italy, for another 42 years. He did not like to hear Culloden or the ’45 mentioned in his old age; these subjects were known to reduce him to tears.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments