By Paul Garson

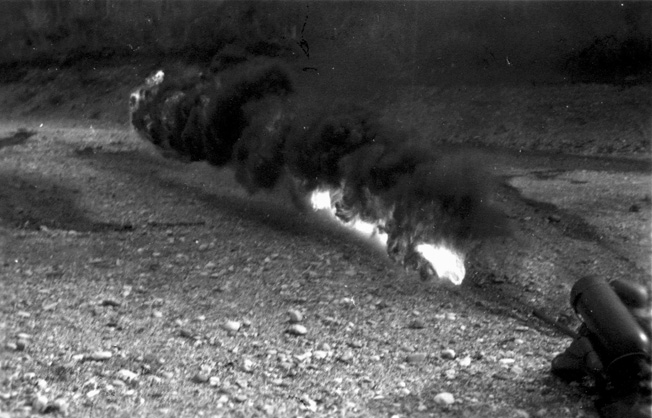

Few weapons in any army’s arsenal are as terrifying as flamethrowers. Just the thought of being burned to death or hideously scarred for life is enough to send even the bravest, most battle-hardened troops fleeing in panic.

Modern flamethrowers, or Flammenwerfern, were invented in Germany in the early 20th century and effectively employed in World War I by German Strosstrüppen (shock troops) and Sturmpioniere (combat engineers).

However, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which placed severe limitations on German armaments, banned the German possession, importation, or manufacture of flamethrowers–strong testimony to their success on the battlefield due, in great part, to their psychological effect.

Flamethrowers Before World War II

After he became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Adolf Hitler made the decision to abrogate many of the provisions of the treaty. He quietly began adding aircraft, warships, and tanks to his nation’s arsenal. He also approved the resumption of the manufacture of flamethrowers.

The use of projected fire as a weapon goes back many centuries. The Greeks used it in naval engagements, and the Byzantines used it in their battles against Arab ships. The Chinese, too, employed flamethrowing devices as a weapon. In 1901, Richard Fiedler, a German inventor, created the first practical working model and sold it to the Kaiser’s army. It saw its first use in battle in February 1915 near Verdun. The weapon’s maximum range was only 20 yards, a drawback that limited its effectiveness, but the element of terror was still strong.

A modern flamethrower is a simple weapon. When the trigger is pulled, a quantity of flammable liquid under pressure is forced out of the nozzle and an igniter in the nozzle sets the liquid aflame as it shoots toward the target.

A mixture of pressurized nitrogene gas and Flammol, a volatile liquid, was ignited by a magnesium-triggering device spewing liquid flame that could easily gain entry into bunkers through their gun slits and incinerate the inhabitants. Soldiers equipped with the device, however, bore a double indemnity as easily identifiable targets for snipers, and were subject to summary execution if captured.

With an effective range of 20 to 30 (later improved to 30-35) meters, surprise and speed in the employment of flamethrowers were necessary when attacking enemy positions. The thick, black smoke also served to produce a “screen,” enabling infantry to quickly follow and seize the tactical advantage. Small, 90-pound portable one-man canister units (Flammenwerfer 34 bez. 35) were introduced in 1934. These were first employed in 1940 to destroy French and Dutch fortifications, bunkers, and gun positions. They were later critical in house-to-house fighting and as a means to implement Germany’s “scorched earth” policy in the East, and for “reprisals.” Flamethrowers were also used extensively in destroying the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland.

The Wehrmacht’s Flamethrowers

The Wehrmacht saw a large role for the flamethrower conceived in several forms— portable, one-man systems; medium mobile wheel-mounted units; tank and armored vehicle versions; and larger fixed weapons as part of defensive fortifications.

The principle testing facility for flamethrowers was located at Kummersdorf, an estate located 25 kilometers south of Berlin. An Army research group was established in Kummersdorf in 1932 under the direction of Walter Dornberger, a leader of Germany’s V2 rocket program and other projects at the Peenemünde Army Research Center. (After 1938, Kummersdorf was also a Third Reich center for nuclear research.)

It was Reichsmarschal Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, who placed the first orders for flamethrowers in that same year, and 1,000 were produced by the beginning of 1939.

The simplified, lighter Fm. W. 41 dual-canister flamethrower, the final approved model, was introduced in 1941. Some 70,000 were produced, and the units dispersed to the regular Army, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, and police battalions, as well as some 1,300 allocated to Germany’s Axis allies.

The largest pieces of apparatus in the German arsenal required a three-man team—two to hold and direct the tube (up to 180 feet long) and a third to operate the tank’s controls.

Flamethrowers on the Eastern Front

The street-by-street, house-by-house, room-by-room fighting encountered in Stalingrad brought about a demand for mechanized flamethrower-equipped vehicles (Flammpanzer), although their effectiveness proved limited and only a relatively few were built, as the panzer bodies were needed for tank production.

After encountering very effective Russian “fixed flamethrowers” on the Eastern Front, the Germans developed their own versions as defensive barrage weapons— items very much in demand as the Soviet Army advanced toward Germany.

The Abwehrflammenwerfer 42, (Defensive Flamethrower 42), when arranged in clusters, could swathe large areas in flame, and some 50,000 of them were eventually placed in service by June 1944. This was a disposable, single-use weapon that could be buried alongside land mines and triggered by either a trip-wire or a command wire.

Germany had plans to use great numbers of these types of weapons at Normandy to forestall an Allied invasion but none were actually employed. American troops, on the other hand, brought their own flamethrowers ashore.

As the war ground to a close, the young boys and old men of the Volkssturm (People’s Army) were handed the Einstoss-flammenwerfer 46 (People’s Flamethrower 46), a compact, very lightweight (less than eight pounds) design. Some 15,000 of the cheaply and quickly producible “pipecartridge-trigger” devices were produced before the end of the war.

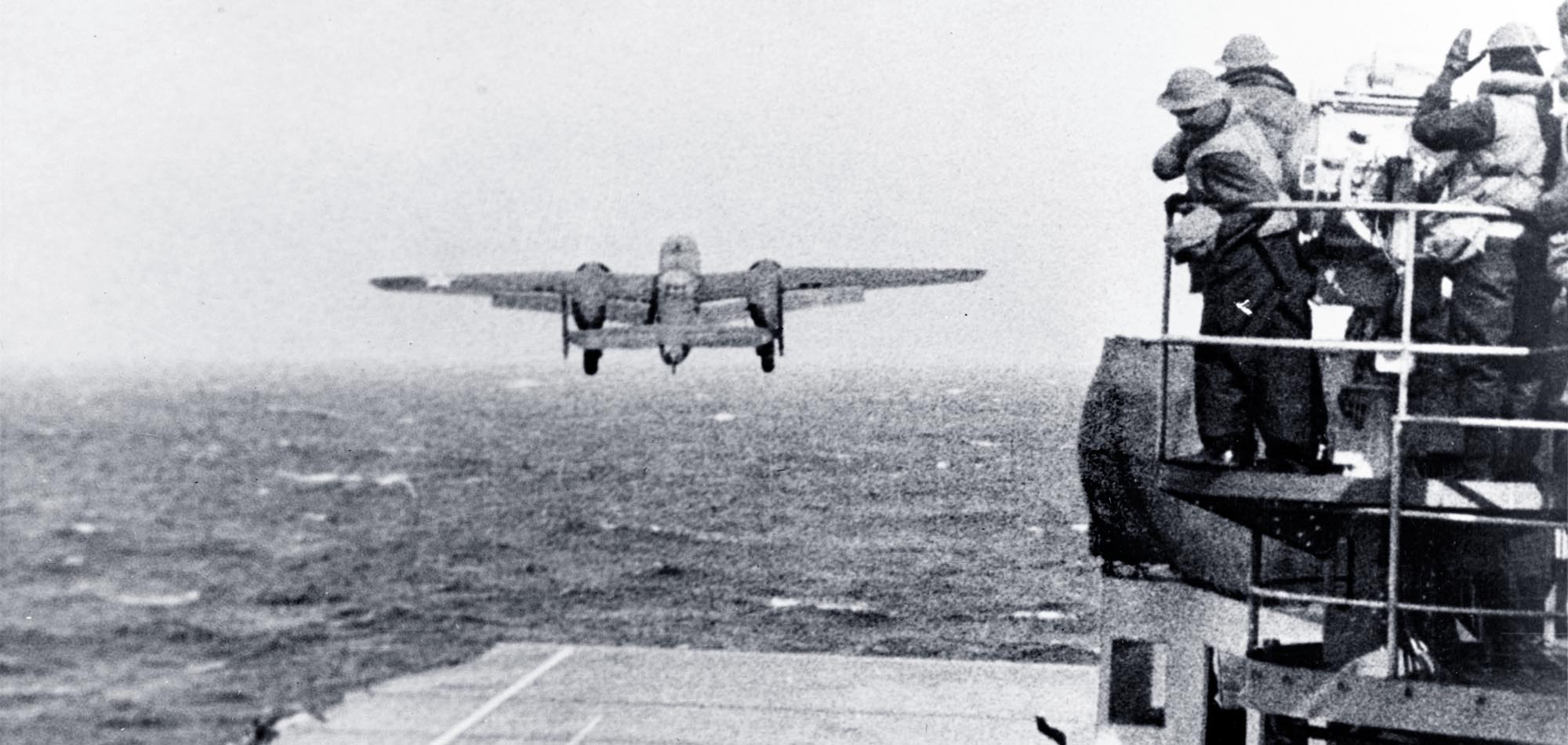

The U.S. military adopted the flamethrower in 1942. Larger versions were also adapted for tank usage by the Americans on both the European and Pacific battlefields. Other countries that employed the weapon during the war include Italy, Japan, Britain, Australia, Finland, and the Soviet Union.

Currently U.S. federal law does not restrict private ownership of flamethrowers; however, ownership is restricted by some state laws, including California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments