By Captain Eugene H. Simpson

The Battle of Savo Island, August 8-9, 1942, was the first major naval engagement of the Guadalcanal Campaign. In response to American amphibious landings commencing on August 7 on Guadalcanal and nearby Tulagi and Florida islands, the Japanese mobilized a task force of seven cruisers and one destroyer. The Japanese task force sailed down New Georgia Sound (“the Slot”) intending to interrupt the landings by attacking the supporting amphibious fleet and its screening force. The American screening force consisted of eight cruisers and 15 destroyers, of which five cruisers and seven destroyers were involved in the Battle of Savo Island.

The Japanese task force thoroughly surprised and routed the screening force, sinking three American cruisers in a matter of minutes and damaging an Australian cruiser so badly it later had to be scuttled. Nearly 1,100 Allied personnel were killed in the attack. The Japanese task force suffered only light damage.

Despite its early success and fearing air attacks, the Japanese task force withdrew after the Battle of Savo Island rather than attempt to destroy the U.S. invasion transports. The American carrier fleet, fearing a Japanese attack, had already withdrawn.

The Japanese attack induced the remaining Allied ships to withdraw before all supplies had been unloaded; this premature withdrawal of the supporting fleet left the Marines on Guadalcanal in a precarious situation, with limited supplies, equipment, and food.

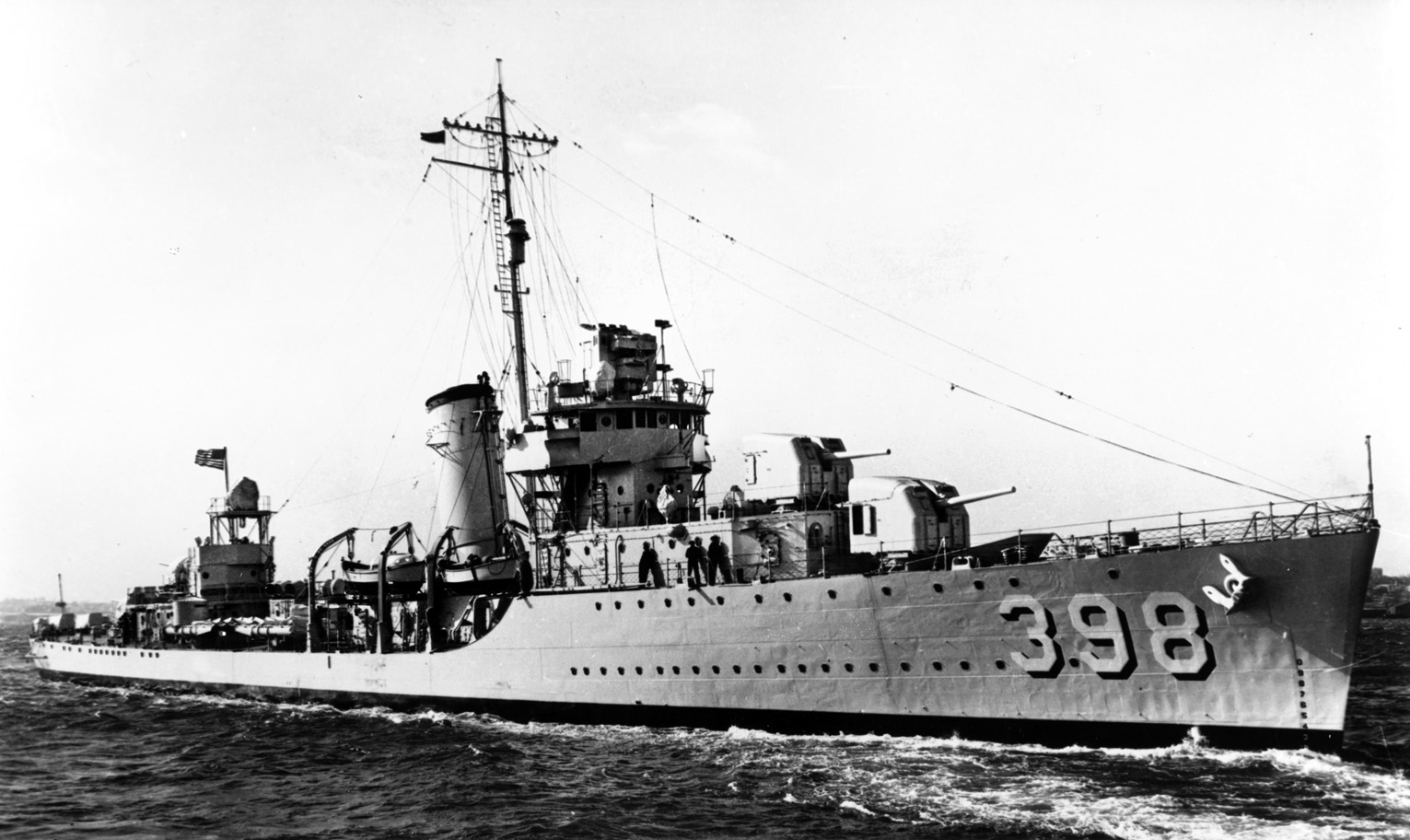

The destroyer USS Ellet arrived off Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942, and led the task force into Guadalcanal and Tulagi Harbor. According to the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, on August 9, the Ellet rescued 41 officers and 461 men from Quincy (CA-39) and one man from Astoria (CA-34), cruisers sunk in the Battle of Savo Island the night before. The Ellet then joined the destroyer USS Selfridge (DD-367) in sinking the hulk of HMAS Canberra, hopelessly battered in the same battle.

The following is the eyewitness account of Captain Eugene Simpson, who was serving as the engineering officer aboard the Ellet during the events of August 8-9, 1942. He provides an inspiring and unforgettable account of the heroism he witnessed:

On the night of August 8 and the morning of August 9, 1942, occurred the most dramatic and traumatic experience that happened to me in World War II.

By way of background, during our approach to Guadalcanal our ship (the destroyer USS Ellet (DD 398)) had prepared to pick up survivors in the event that some of our ships were sunk. We had some serious discussions concerning how it was to be done. We actually held a couple of drills manning our survivor pickup stations.

We divided the ship into three main areas:

(1) Those survivors who appeared to have major injuries were to be sent to the wardroom, which was just forward of the break in the main deck. Our doctor, who was an obstetrician in civilian life, would man the wardroom operating table along with one corpsman.

(2) Those personnel who were wounded in some manner but could still manage for themselves would be routed to the forward living and berthing spaces. Our chief corpsman would be in charge there.

(3) Those that appeared to be uninjured or simply in shock would be routed to the after living spaces and sent below. One corpsman would be in charge there.

The after-boiler room, the entrance to which was just forward of amidships, would be manned to make hot coffee, which could be laced with torpedo alcohol if necessary. Torpedo alcohol was pure grain alcohol, and I was the custodian. I kept it in my room just forward of the wardroom under lock and key.

Our officers were stationed as follows: The first lieutenant manned the forecastle. Since I was the engineer officer and the engine room was approximately amidships, I had charge of the amidships port of the ship. The junior ensign had charge of the fantail, or after portion of the ship. All stations had cargo nets that could be put over the side for the survivors to climb up. There were three volunteer swimmers each rigged with a halter to which a line could be attached. They each carried a bucket with their lines neatly coiled so the lines would play out easily. The idea was that with the ship stopped, it could not be maneuvered. If a man was in the water some distance from the ship, a swimmer would go over the side and proceed to the man. Then the man and the swimmer could be pulled back to the ship by the line attached to the swimmer’s harness.

My station amidships was the most logical place to bring people aboard. There were four quadruple torpedo tubes there with a small torpedo davit behind each one. As time went by, we equipped these torpedo davits with a rope-supporting strap so that a wounded man could be placed in this sling with the sling either under his arms or under seat and be hoisted aboard. Little did we know how useful these preparations would be.

At midnight on August 8, I took over the watch as officer-of-the-deck. We had been at general quarters all day. We had started out by supporting the Marines on the Tulagi side of the bay by gunfire. Then, we had steamed out in the bay to face the torpedo attack by the Japanese two-engine bombers. After this, we resumed our fire-support mission for the Marines on Tulagi.

We had gone to a watch status about 9:00 that night. Everyone was dead tired, with most of the men off watch sleeping somewhere near their general-quarters station. The captain had a lean-to constructed on the portside of the superstructure just behind the bridge. He was sleeping in this pipe-rail bunk under a canvas to ward off rain. The night orders had word that some Japanese warships had been sighted some hundreds of miles up the coast, but there was no thought of their arriving before morning.

Our afternoon bombardment had started a large fire on the Tulagi side, and we were steaming back and forth at slow speed using the fire as a reference point on when to turn and maintaining our distance from the beach by the use of the air-search radar, and by using eyesight. Our charts were prepared by a Russian survey in 1905 and were very unreliable, especially in regard to depth of water. They did give, however, the general outline of the island and prominent landmarks.

Three cruisers, USS Quincy (CA-39), USS Vincennes (CA-44), and USS Astoria (CA-34), were steaming in column with a destroyer screen well to the east of us. I had dimly sighted them once about 1:00 am. The sky was overcast with moonlight shining through intermittently. There was occasional rain.

Suddenly, at almost exactly 2:00 am the TBS (Talk Between Ships) loudspeaker located on the bridge erupted into sound, “Warning! Warning! Three ships sighted off Savo Island.”

I turned around and automatically hit the general alarm that started squawking immediately, ordered the boatswain’s mate to sound general quarters over the loudspeaker system, and rushed around the port corner of the bridge and hit the canvas of the captain’s lean-to with my open hand. “Captain, someone just yelled ‘three ships off Savo Island,’” I reported.

The captain raised up in his bunk, hitting his head with a violent thump on the pipe-rail extension over his head. I heard his feet hit the deck as I hustled back onto the bridge. Just about this time, a full salvo of heavy caliber guns went off in the vicinity of Savo Island. Several shells went roaring overhead and some ricocheted down the water some distance from us on our port side.

By this time the executive officer, LCDR J.D. Whitfield, was on the bridge and demanded to know where we were. I told him as best I could. He relieved me, and I hustled below to the engine room.

As I slid down the polished handrail on the ladder leading to the engine room, I shouted to Chief Vaughn, my trusted leading chief petty officer, “Have you got Big Ben open?” “Big Ben” was a large valve on the main steam line that admitted high-pressure steam directly into the intermediate-pressure turbine and was only opened when speeds of more than 30 knots were required.

“Of course,” he replied. “We’ve got all boilers on the line, too,” he said. There was nothing for me to do but stand there and watch. There was a battle going on—we could hear guns going off at a distance.

Suddenly the annunciator rang, and it registered “All Ahead Bendix.” The annunciator was marked off in sections—Ahead 1/3, Ahead 2/3, Standard, Full, Flank, and then the last section was marked “Bendix Mfg. Co.” When the annunciator rang up “Bendix,” it meant “give her all you’ve got,” and the throttle was gradually opened all the way without dropping the steam pressure too much, eventually resulting in full power being generated.

We immediately felt the acceleration in our feet as the throttles were opened. Suddenly the annunciator went from “All Ahead Bendix” to “Stop.” As the big throttle was closed, I heard the safety valves lift on the boilers and I cursed, but then came the order to “Back Full,” and that took all the steam. Then “Ahead Flank” followed by “Back Full” and then “Stop.” Then over the loudspeaker came, “All hands man your rescue survivors stations.”

I emerged from the engine room to the main deck to a scene of utter chaos. Everywhere I looked on the starboard side, there were men in the water, all yelling for help. Some were trying to swim to the ship, but most were in life rafts or life nets and they could not move. An occasional shark could be seen, too. They, of course, were busy.

Most of the men designated to man the amidships station had, by now, appeared. The first thing was to cut the lashings on the cargo nets and to rig them over the side. I remember looking at my swimmer with his line tender thinking of the sharks and saying, “Are you ready?” He said, “Hell yes, let’s go.” I pointed to a large net full of swimmers and said, “Get them.” And he went over the side with a dive and swam strongly to the net. When he reached the net he waved his arm and we slowly pulled the whole mess alongside, maybe 30 or 40 men.

They were all in shock, with extremely white faces and a sort of vacant look. A lot of them could not climb the nets and had to be assisted. There were plenty of wounded ones, too, both from shell fire and shark bites. I saw one shark leap into a net and lay there thrashing about with jaws snapping until the shark was thrown out by the men in the net.

All of the swimmers congregated amidships as the life nets and rafts started arriving. To their credit, I did not see one hesitate to immediately turn around and head back for another net or raft after they were pulled alongside.

As one of the first groups was pulled aboard, a tall officer came up to me and said, “I’m a doctor and (pointing to another officer) so is he. Where do I go?” “You belong in the wardroom,” I said, pointing the way, “but you better have a short of coffee and alcohol before you go.” I pointed to the after-fireroom hatch, and he went below to emerge a short time later.

By this time, my people were carrying out the basic plan, laying the people who were badly wounded out like cordwood on the starboard side just aft of the wardroom. Those that were able to walk, but were bloody, were sent forward up the portside and down into the forward living spaces and mess hall, and the people who appeared to be unwounded were sent aft and down into the aft living spaces.

I had read of the great sea battles in the days of sail with John Paul Jones and Lord Nelson. I remembered that the white decks had run red with blood. That’s exactly what happened to us that night as blood ran down the main deck from those people waiting to get into the wardroom to see the doctors. It wasn’t too long before I sent a sailor into the superstructure aft to get a bucket of sand to put on the deck. It was getting too slippery to stand on. About 4:30 am we started running out of survivors to pull aboard, and it began to be daylight.

The people in the after fireroom called up that they had run out of alcohol. I decided that things were calm enough that I could go forward and bring back another gallon. I picked my way up the starboard side, carefully avoiding the people laying there, and entered the wardroom.

There were people all over the wardroom, and blood was everywhere. The wardroom table had one of those big operating lights over it, and it gave out a bright, garish light illuminating the whisker stubble on the white faces of the doctors and their helpers. As I went through the entrance en route to my room on the starboard side just forward of the wardroom, I saw that the wardroom table was covered with a bloody sheet, and a man was stretched out on it. He was bandaged in various places. One of the doctors was leaning over him with a stethoscope listening to his heart. “He’s dead,” said the doctor.

Our doctor spoke up and said, “Well, he just died, then. He was alive a few seconds ago.”

Another doctor said, “Let’s start his pump up.” With that, he jabbed a needle that looked about four inches long into the man’s chest. I could see his heart start pumping. Someone said, “No pulse.” Another said, “Let’s give him something to pump.” He hung a bottle of plasma overhead and put the needle into the man’s arm. That man was alive and conscious when we transferred him in the morning.

I picked my way through the wardroom and entered my room. It had two bunks and both contained men. I got my alcohol from the locked drawer. As I turned to back out, I noticed that the man in the top bunk was lying in the bunk with his arm extended out to one side. I said to myself, “I’ll fold that arm back across his chest.” I reached up to do that. He was dead and rigor mortis had set in. The arm was rigidly stiff. I carefully left him just the way he was and made my way back to the midship station.

So passed the night of August 8 and the morning of August 9, 1942. The cruiser Astoria burned all night like a Ku Klux Klan fiery cross in the darkness. The Quincy and Vincennes had gone down, struck by torpedoes. We picked up 547 people, which was quite a load for a destroyer whose normal wartime complement was just over 300 personnel.

Just before 8:00 am on August 9, we were ordered to proceed to the east of Savo Island and assist in sinking the Canberra, an Australian cruiser. We found out later that she had been out in the middle of the bay when the attack came, and she went to full speed to join the battle. As she headed for the action, she caught at least one torpedo in the bow section of the ship. The Canberra pursued the enemy eastward nevertheless and eventually was stopped by progressive flooding and was forced to abandon ship.

Several destroyers had come alongside the Canberra and taken off all personnel. As we headed for the scene, all of the survivors we had on board went out on the main deck and 01 levels. The ship quickly got top heavy. We managed to get the survivors back below and the ship became stable again.

When we arrived on the scene, we were ordered to torpedo the Canberra, which was down by the bow and listing slightly. Our torpedoes were equipped with the MK6 magnetic exploder. As we drew parallel to the Canberra, we fired one torpedo directly under the bridge. When the torpedo exploded, instead of a spectacular geyser of water appearing, there was only a large muddy looking bubble. The entire ship, however, staggered and shortly afterward sank by the bow, disappearing with the propellers being the last part to go under. Thus, we had the dubious distinction of sinking one of our allies’ ships in the first battle of Savo Island.

We transferred the survivors about noon to a transport at Guadalcanal that was acting as a hospital ship. It took about two days to clean up the Ellet. I’ll never forget that night and the sight of the sharks tearing at the rafts and trying to get at the wounded.

Captain Eugene H. Simpson (1916-1991) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1939. He served on board destroyers in the Pacific from February 1940 through 1945. He served on the Benham-class destroyer Ellet and later served as executive officer on the Fletcher-class destroyer Hailey.

While serving on the Ellet, Simpson participated in escorting the aircraft carrier Enterprise carrying a Marine aviation unit to Wake Island in December 1941 (returning to Pearl Harbor the morning of December 8) and escorting the aircraft carrier Hornet when it launched General Jimmy Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo in April 1942. Simpson participated in numerous battles and campaigns, including Coral Sea, Midway, Guadalcanal, New Guinea, Eniwetok, Leyte Gulf, Saipan, Guam, and Okinawa. He was awarded the Bronze Star with V for his fighter-director work while the Hailey was operating on the picket line at Okinawa.

The introduction to this story was prepared and the account edited by Mary Penn Mount, Captain Simpson’s daughter, and Jay E. Grenig, Captain Simpson’s nephew. Neither remembers the captain ever speaking of his wartime experiences. Fortunately, his son-in-law encouraged him to write down many of his most memorable experiences.