By Sam McGowan

In the 1960s the John Birch Society was well known to most Americans as a right-wing political organization noted for its anti-communism and conspiracy theories. Yet few knew anything at all about the man whose name the organization bore. Most assumed that John Birch founded the society, and even members of the organization knew only that the real John Birch was a missionary who became an intelligence agent in China and died at the hands of Chinese Communists in the closing days of World War II.

While his death as the “first American soldier killed in the war against communism” was considered heroic by adherents of the society’s principles, few knew that Captain John Morrison Birch not only was truly a hero, but that his actions in World War II rival those of the most swashbuckling Hollywood spymaster. Even fewer Christians realize that, even though Birch was an Army Air Forces intelligence officer, he was also a dedicated defender of the faith who continued to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ in China even after he had undertaken a new mission serving his country.

John Birch was born on May 28, 1918, in India, where his parents were serving as missionaries. Two years later the family returned to the United States because of his father’s ill health, first settling in New Jersey, then moving to Georgia when John was in his early teens. When the family decided to return to the Birch farm near Macon, John and his younger brother went down and cleaned up an abandoned house for the family to live in and planted the fields, which gave him a strong bond with the land and an appreciation for the outdoors.

Born with keen intelligence, as a boy John was fascinated with airplanes and aeronautics. After the family moved to rural Georgia, he became interested in radios and designed and built his own set, using the cardboard centers from toilet paper rolls and copper wire to make coils. Raised in a devout Christian home, John was baptized into a Baptist church in New Jersey at the age of seven. His parents had left their Presbyterian church because they believed the denomination had become modernist, and they joined a nearby Baptist congregation. When he was 11, John decided to become a missionary after hearing one describe his adventures in South America. After graduating from high school, John enrolled at Mercer University, a Baptist school in Macon, from which he would graduate first in his class.

Two major events occurred during Birch’s years at Mercer. The young man fell under the influence of J. Frank Norris, a legendary and controversial Baptist preacher from Fort Worth, Texas. During a service in Macon, Birch heard Norris tell about the accomplishments of two missionary families in China and how they were praying for a strong young man to come to China to work with them. During the invitation at the conclusion of the service, Birch went forward and told Norris that God was calling him to China and he would go. Shortly afterward, Birch became involved in a campus controversy when he and other members of the ministerial student body brought charges against members of the faculty for teaching things that were contrary to Baptist doctrine. An uproar resulted, and fellow students branded Birch as the vilest person on campus. He was threatened with expulsion but held true to his convictions and refused to go along with demands made by the college dean to cancel a planned city appearance by Norris. The controversy was settled when Norris inexplicably canceled the meeting.

True to his word, immediately after his graduation from Mercer, John Birch began the journey to China by enrolling at Norris’s Fundamental Baptist Bible Institute in Fort Worth. He completed the two-year seminary course in a year, and in the summer of 1940 set sail for Shanghai, along with another graduate named Oscar Wells. They arrived to find a country in disarray, with thousands of refugees from the country crowding the streets and disease and starvation on every corner. China was literally divided, with Japanese troops occupying much of the central coastal areas, Communists in the northern mountains, and Free China to the west. They were met by Fred Donnelson, who took the two new missionaries to his apartment, where they met the other members of the World Fundamental Baptist Missionary Fellowship team in China, which consisted of Donnelson and his wife, Effie, an elderly missionary affectionately known as Mother Sweet, and her partner in the mission field, Margaret Fitzgerald.

Birch and Wells enrolled in the Adventist Chinese Language School in Shanghai, where Birch’s zeal and intelligence allowed him quickly to gain a working knowledge of the language. He felt called to minister in the distant towns and villages away from Shanghai and the coast. Hangchow was the city that was on his mind, and he finally got the opportunity to visit it when J. Frank Norris’s associate, Beauchamp Vick of Detroit Baptist Temple came to China.

John was convinced this was where he should minister and he returned to Hangchow in early 1941. From then on, his ministry was in the inland regions of China as he ventured out from Hangchow to preach in the villages and towns in the surrounding no-man’s-land where Chinese guerrillas fought Japanese troops. In August, he was visited by his friend Oscar Wells, who was ministering in Shanghai, where he had met and become engaged to a young female missionary from the Reformed Church. Along with Pastor Du, the Chinese pastor in Hangchow, the two young men set off on a journey to Shangjao, a city in the mountains in Free China almost 200 miles away. Journeying by bicycle and on foot, they slipped through the Japanese lines then made their way westward until they were well into the mountains. As they left Japanese territory, they realized that the food was better and the people happier. When they reached Shangjao, they were directed to the Baptist church and were invited to conduct services that evening. The local Christians were eager to host the missionaries and told Birch that there were many places to the west where they could establish churches. He promised to come back.

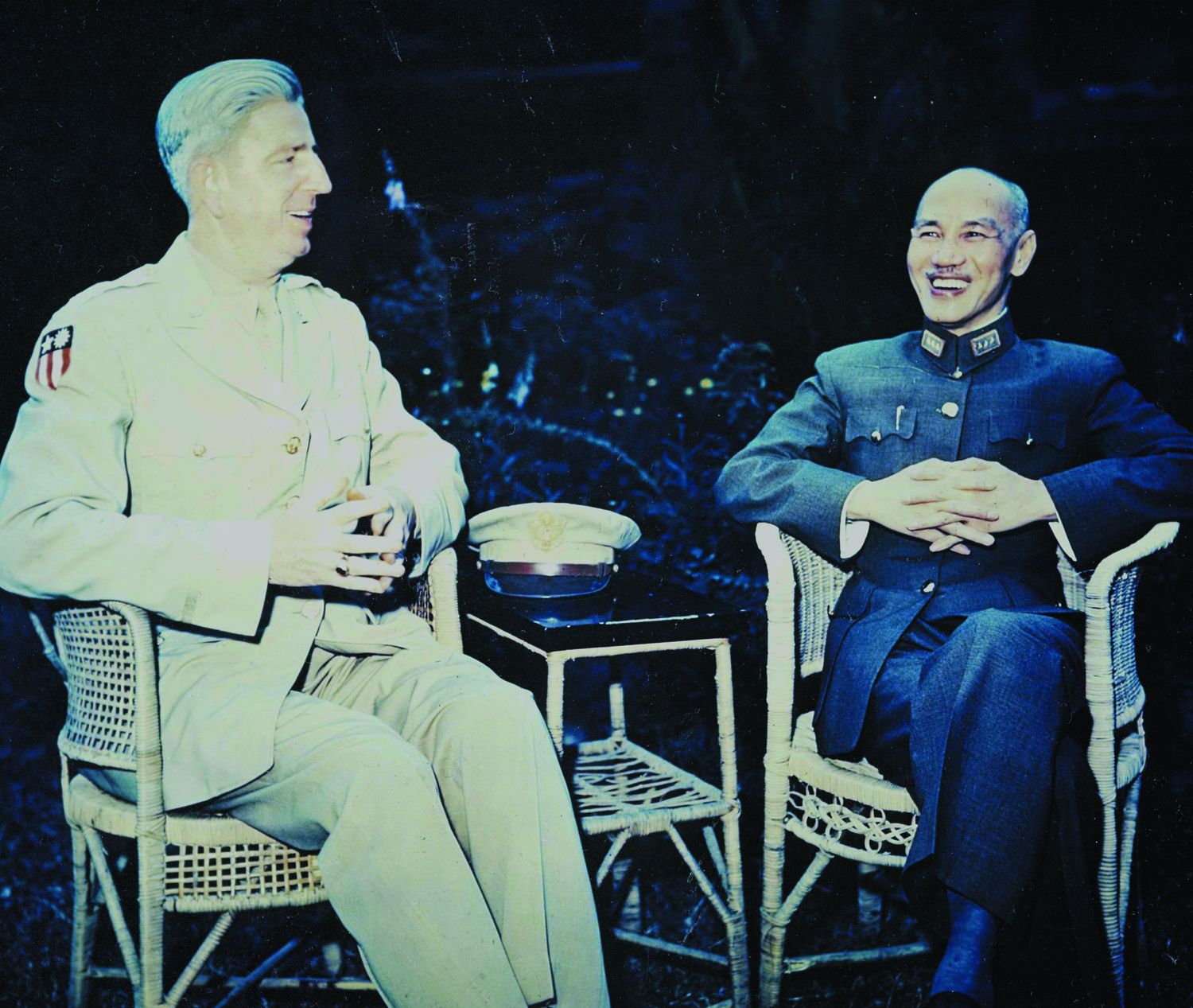

Birch made friends with dozens of Chinese pastors during the next few months and established relationships that would later prove beneficial. Many Chinese Christians were involved in the guerrilla movement, while others were members of the Nationalist army. Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Madame Chiang, were both Christians, and Chiang had written a tract about his belief in Jesus Christ that was passed through the ranks of the army. Birch was more than welcome among the Nationalist troops, and he was encouraged to preach to them. But clouds of war were gathering, and American missionaries were told to get out of the country. Many decided that their place was in China, and even though they knew that if the United States entered the war they would be interned, the Donnelsons, Mother Sweet, the Wellses, and Birch all elected to stay.

In November, John was scheduled to take a language exam in Shanghai, so he journeyed through the Japanese lines to Hangchow and caught the train to the city. He finished the exams on a Friday and left the next day for Shangjao. He arrived in Hangchow and visited some Presbyterian missionaries, who encouraged him to spend the weekend. Birch felt he should be on his way and refused the offer; he told his friends that if he did not appear at breakfast with them the next morning, he would have already slipped through the lines on his way into Free China. The next day was Sunday, December 7, in China and Saturday in the United States. Had Birch accepted the invitation to remain in Hangchow for the weekend, he probably would have been interned by the Japanese. He got word of the attack on Pearl Harbor from Chinese soldiers he met on the road.

Over the next six months, John Birch was a stranger in a foreign land, cut off from his friends, who had been interned by the Japanese, and with little funds. He had some traveler’s checks, but the Chinese banks in Shangjao refused to cash them. Still, he continued his ministry, preaching in homes and churches in the mountains around the town. In April 1942, he wrote a letter to the U.S. military mission in Chungking inquiring about the need for someone with his qualifications. His first choice was to be a chaplain, but he offered to do whatever was needed. In the letter he mentioned his knowledge of radio and stressed his ability to withstand physical hardship. Three days later, the Chinese Army cashed his checks and he sent most of the money to his friends through a courier who had made the long journey to inform him that they were interned and in need of funds.

On April 27, John Birch was sitting in an inn in a remote river town when a Chinese man sat down at his table and asked if he was an American. Sensing that he might be watched, Birch silently nodded that he was. The Chinese told him to finish his meal, then follow him, but to be careful that they were not seen. The man led the missionary to a sampan sitting low on the water. He nodded toward the boat and said, “Americans.” Birch was incredulous—how could any Americans be out here in the middle of China? As far as he knew, he was the only American within hundreds of miles. He knocked on the door of the cabin and called out, “Any Americans in here?” After a moment of silence, a voice from inside said, “No Japanese could mimic an accent like that,” and the door swung open. He looked inside and saw five Americans dressed in military uniforms. The leader stuck out his hand and said, “I’m Jimmy Doolittle. We just bombed Tokyo.”

Birch was with Doolittle and his crew for barely 24 hours, but the young missionary made an impression on the veteran pilot. Doolittle told Birch to write down any notes or letters he wanted delivered, and he would take them back to the United States. Birch stayed with the sampan until it reached its destination, then guided Doolittle and his crew to a Chinese Army post at Lanchi. He told the officer in charge who the men were and asked if they had word of any other fliers. The officer asked Birch to inform Doolittle that the Chinese Army was doing everything possible to prevent any of the airmen from falling into Japanese hands. Birch continued on to Shangjao where he found a telegram from the Army telling him to report to the nearest air base at Ch’u Hsein and await further orders.

When he arrived at the airfield, Birch found two other American bomber crews who were badly in need of an interpreter. Birch made arrangements for a flight to take them to Chungking. He received a phone call from a missionary in Yang Kou, who told him that Doolittle had left money and instructions. Another crew arrived as he was preparing to leave to pick up the money. Doolittle had left $2,000 in Chinese money and instructions to arrange for the burial of Corporal Leland Faktor and any others whose bodies might be brought in, to arrange for medical aid, to obtain all information pertaining to survivors, and to serve as an interpreter for crews who came to the field.

When the last crew left, Birch was to go with them and report to the U.S. military mission at Chungking. Over the next several days, Birch was able to account for 60 of the Doolittle Raiders. When Birch asked the military commander about purchasing a burial plot, the Chinese said he would not sell it to him but would give it for a hundred years or as long as needed. The Chinese also paid for the coffin and the cost of the marker. Birch conducted a memorial service for Faktor with 13 Doolittle Raiders present, then two weeks later conducted a graveside service.

Birch did not make it out on the last plane; instead he made his way to Kweilin by truck, on foot, and by train looking for Claire Chennault, who he had been told was there at his forward operating base. He found the American Volunteer Group (AVG) commander in his operations cave on the side of a mountain. When he introduced himself, Chennault revealed that Jimmy Doolittle had spoken of him and the aid he had provided to the members of the mission to bomb Japan. Birch replied that he wanted to be a chaplain, and Chennault asked which denomination. When Birch said he was a fundamental Baptist, Chennault replied that he was a Baptist himself, a member of a congregation in Louisiana.

Birch told Chennault that he wanted “to serve God and my country.” Chennault said he already had one chaplain but might be able to make him an assistant. Birch asked Chennault for a ride to Chungking and was told to meet him at the airport. Birch was there at the appointed hour, and he climbed aboard the airplane with Chennault himself at the controls. When they landed, Chennault took the young missionary to Hostel A, where he and his pilots stayed, and arranged for a room.

Birch arrived in Chungking in late May, at a time when the U.S. military role in China was developing. Although he held the rank of general in the Chinese air force, Chennault had yet to be brought back into the United States Army, from which he had retired a few years previously. After seeing that the young missionary had a place to stay, Chennault turned him over to a U.S. Army officer for a debriefing on his activities with the Doolittle Raiders.

It was at this point that Birch detected an air of superiority among the Americans, an attitude that directly affected the conduct of the war in China. When Birch turned in the $2,000 Doolittle had left for him and related that the Chinese Air Force had paid the costs of the burials, the debriefing officer was incredulous. Birch had grown to love the Chinese and was offended when the American commented, “All of the Chinese we’ve dealt with have their hand out.” Such an attitude was common among the Americans who made up the China military mission. Birch was soon to learn that many Americans, including their commander, Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell, preferred Mao Tse-tung’s Communists over Chiang’s Nationalists. Birch could not believe his eyes when he visited the American Office of War Information and found a pamphlet praising Mao’s revolutionaries.

Birch also learned that most of Chennault’s AVG men would soon be leaving. With the exception of a few who agreed to accept induction into the U.S. Army, most refused to serve under Colonel Clayton Bissell, the U.S. Army officer who replaced Lt. Gen. Lewis Brereton as commander of Tenth Air Force in India and whom General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold had picked to command U.S. air operations in the theater. The pilots and mechanics of the AVG were all former military personnel who had been recruited from the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, and the former naval aviators were particularly turned off when they were told they would become part of the Army instead of returning to their previous branches of service.

When Birch arrived in Chungking, the transition to the Army was still a few weeks in the future, so he decided to delay his entry. As an ordained minister, he was exempt from the draft and could not be inducted. His impression of Chennault had been highly favorable, and he decided he would prefer to serve directly under him. The admiration was a two-way street; Chennault had been equally impressed with the young missionary, and while he was willing to let him go through the motions of applying for an appointment as a chaplain, he realized he could be far more important in another role.

Over the next few weeks, Chennault and Birch were frequently together. On an occasion when Chennault invited him to ride into town, he brought up a new subject. He told Birch he had a need for field intelligence officers with experience in China, men who had lived there before the war, spoke the language, and were familiar with Chinese customs. He told Birch how important the work would be to the winning of the war and that it would be extremely dangerous. The punch line was when he told the young missionary that he would be free to preach on Sundays if he chose to accept a commission as an intelligence officer. There was one thing Chennault wanted, and that was total commitment. He told Birch that if he decided to accept the job, he would give him an immediate field commission. Birch said he would pray about it.

On July 4, Birch attended a barbecue hosted by the first lady of China, Madame Chiang (formerly Soong) herself, and General Chennault, held at the home of the Chinese president, Lin Sen. Birch was surprised to get an engraved invitation. Madame Chiang’s sister, the widow of the founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat Sen, was also present. When Birch came through the receiving line, Chennault introduced him to the Soong sisters as “a missionary who helped General Doolittle and his flyers.” Birch and the Soongs had something in common; the sisters’ father was a Methodist minister, and as young women they had attended Wesleyan College in Macon. They were thrilled to learn that Birch was from Macon and greeted him warmly.

Another member of Chennault’s entourage was also from Macon. Colonel Robert L. Scott, who would take command of the 23rd Fighter Group, was a Macon native. Although the two knew each other—Birch was part of the 23rd Fighter Group—the young missionary was not the inspiration for the title of Scott’s famous book, God Is My Copilot. The title came from a comment made by another missionary, Dr. Fred Manget, who treated Scott for minor shrapnel wounds.

On July 5 at breakfast, Chennault again approached Birch about becoming an intelligence officer. Birch told Chennault that he thought he knew what the delay was; although he met most of the requirements for being a chaplain, J. Frank Norris’s school was not accredited, and graduation from an accredited seminary was a requirement. The senior chaplain in Chungking had told Birch he would request a waiver, but no word had come down. Chennault told Birch he could accept a commission as an intelligence officer and transfer to the chaplaincy later if an appointment came through. The concession excited Birch, who immediately accepted. Chennault had the paperwork drawn up and commissioned John M. Birch as a second lieutenant assigned to the 23rd Fighter Group as the group intelligence officer.

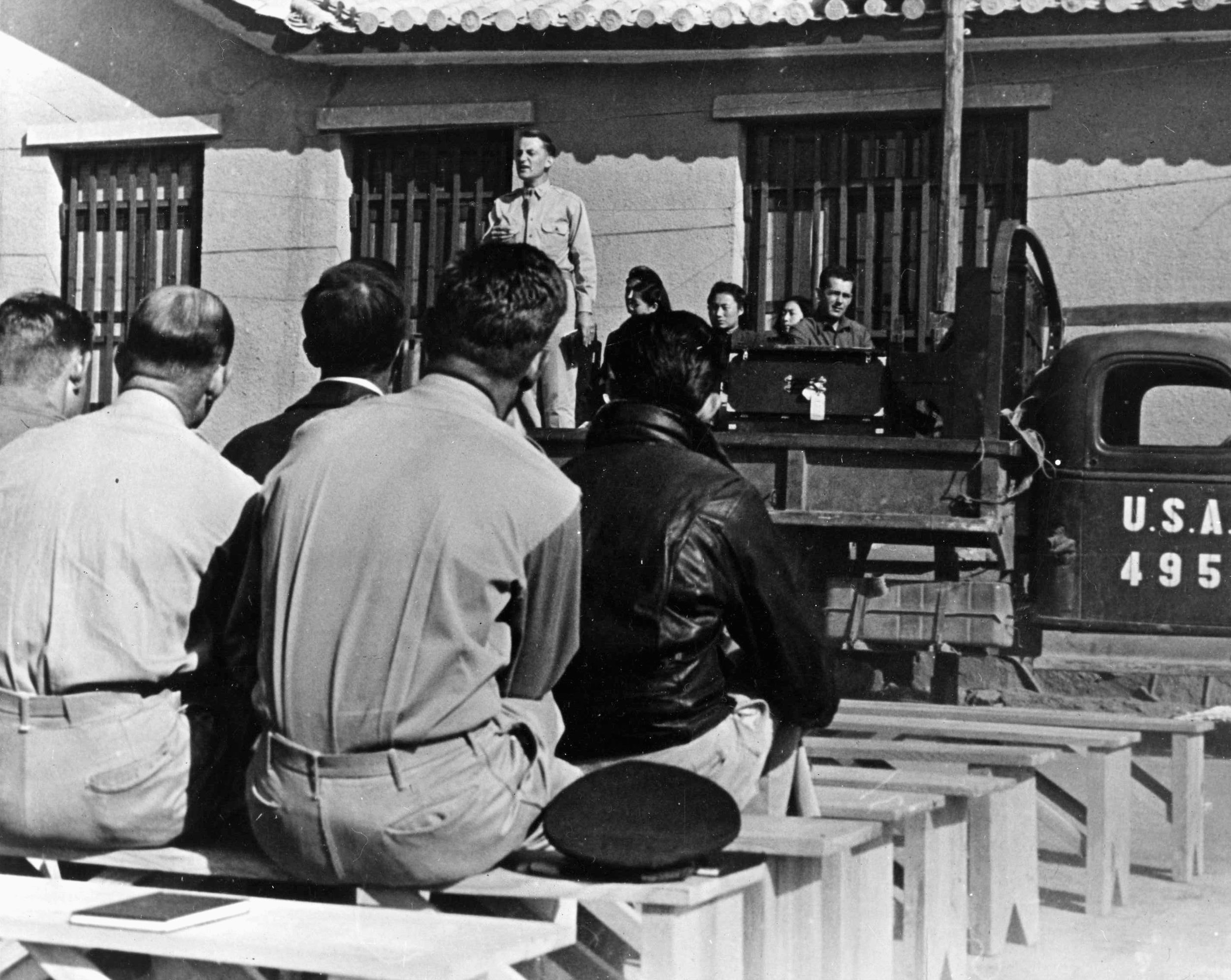

Although he had been commissioned as an intelligence officer, Birch volunteered to assist Chennault’s chaplain, Paul Frillman, another missionary who had joined Chennault’s staff in the Chinese Air Force and had come into the U.S. Army as a chaplain. Frillman would later become an intelligence officer himself. Frillman was Lutheran while Birch was a fundamental Baptist, and although there was disagreement between the two over issues of personal conduct, Frillman made Birch his assistant and assigned him to preach at Sunday services when he was absent and to orient new personnel to the theater.

Birch was still focused on becoming a chaplain, and when he learned that the chief of chaplains for the CBI was coming to Chungking, he requested that his file be reviewed. The request was approved. When he went to tell Chennault the good news, the Old Man told Birch he wanted him to go on a mission for him. Birch agreed, under the condition that if the appointment came through, he would be allowed to transfer. Chennault countered by asking Birch whether he would remain as his intelligence officer if the appointment did not come through. Birch said he would, and the two shook hands.

Birch’s mission was to journey into southeastern China to inspect clandestine airfields that Chennault had ordered built two years previous and had stocked with gasoline and ammunition. Chennault wanted to know the condition of the airfields and supplies so he would be able to use them as forward airfields if the need arose. Birch and a Chinese soldier named M.L. Wang left on the mission in mid-September. It was the first of many long treks into contested territory. They took only what they could carry. Birch also carried maps, a list of contacts, and a roll of gospel tracts written in Chinese to pass out along the way. They covered more than 1,000 miles on the two-month journey, traveling by land, water, and air. When they were in Japanese-controlled territory, they moved by night. Birch’s contacts, many of whom were Chinese Christians, allowed them to sleep in their homes, and on Sundays he was usually offered the opportunity to preach in homes and local churches.

Birch and Wang inspected the airstrips and asked the contacts to show them the supply caches, which had been ingeniously concealed. Gasoline cans and ammunition boxes were buried under pagodas, hidden in corn cribs, suspended on ropes in wells, hidden in caves, and buried underground. Birch was pleased to discover that local villagers had kept the airstrips in good condition. When they returned, Chennault read Birch’s report and immediately wrote a letter of commendation for his personnel file and recommended that he be promoted. It was the first of several recommendations for Birch’s promotion made by Chennault, along with recommendations for decorations, but the convoluted command structure in the CBI required that they be approved by Tenth Air Force Commander Clayton Bissell, who was quick to disapprove just about any recommendation Chennault made.

The command arrangement in the CBI caused many problems. Although the War Department apparently originally saw China as a base for an aerial bombing offensive against the Japanese home islands, the Japanese victory in Burma and the offensive in China in the wake of the Doolittle Raid caused the theater to lose its importance. General Stilwell went to China as the senior American officer, but he had little regard for Chiang and the Nationalists and was focused entirely on avenging his defeat in Burma. Stilwell and nearly everyone else in any position of authority were jealous of Chennault’s relationship with Chiang and the military successes of his shoestring forces in the Chinese interior.

Hap Arnold hated Chennault and had been forced by the White House to accept him as the senior air officer in China. He had seen to it that Chennault’s authority was diminished by making him subordinate to Bissell. He wrote the orders promoting both of them to brigadier general so that Bissell outranked Chennault by one day. He also placed Chennault’s China Air Task Force (CATF) under Bissell’s Tenth Air Force and required that Chennault go through Bissell with every request. Birch’s family would learn after the war that he had been recommended for every combat decoration up to and including the Medal of Honor, but the recommendations were all mishandled except for the Legion of Merit and Distinguished Service Medal. Bissell and his staff disapproved most of the recommendations for decorations submitted from China on the basis that the men were “just doing their duty.” The attitude led to great resentment against Bissell and his staff, who were safe in offices in Delhi.

Birch learned that no authorization for him to become a chaplain had come through, so he accepted the position as Chennault’s intelligence officer. Chennault told him that he was his “intelligence department” and would answer directly to his command. Birch’s office was a shack a few yards from Chennault’s headquarters. His first duties were to make corrections to aerial maps and debrief pilots returning from missions. He would be in charge of all intelligence, no matter from what source. A few weeks later he discovered that Bissell had decided to take over the intelligence department as well, without consulting with Chennault.

On December 10 two officers arrived at Kweiling, where Bissell had ordered Chennault to relocate his headquarters, and informed Chennault that they had been sent by Bissell to become his chief intelligence officer and assistant. After his initial meeting with the two officers, Chennault ignored them for more than a week. He told them that he did not appreciate Bissell picking his staff and that he already had an intelligence man, Lieutenant John Birch.

The two officers were actually well qualified and did not appreciate being caught in the middle in the war between Bissell and Chennault. Lt. Col. Jesse Williams had been in Shanghai for 18 years as an oil company executive, while Captain Wilfred Smith was the son of missionaries and had studied oriental history at the University of Michigan. Neither had the kind of experience Birch did, but they were well qualified to serve as intelligence officers in China. They finally decided to ignore Chennault and go to work. They went to Birch’s office and told them who they were. It was an uncomfortable moment as Birch answered directly to Chennault on his order, and he commented to the two officers that Bissell was not too popular in that part of the world. Yet, he recognized that they were superior officers and told them to pull up a chair and he would show them what he was doing. The three men got along well together and soon all were laughing over the feud between the two generals.

Although he was an intelligence officer, Birch still had the opportunity to preach. He was amazed to discover that the American military personnel responded to him better than they did to the chaplain. The young soldiers and airmen realized that Birch did not have to be in the Army because as a member of the clergy he was exempt from the draft, yet he was undertaking dangerous assignments far from friendly lines. He had thought that he could best serve God as a chaplain but discovered that he was more effective in the spiritual role in a different status. He was also able to continue ministering to Chinese Christians when he went out on intelligence-gathering missions in the countryside.

In early 1943, Chennault was finally promised reinforcements. He went to Williams and Smith and told them he needed intelligence from the coast. He wanted his own intelligence network in China so he would not have to rely on Stilwell’s headquarters, which usually was a week or more late in passing on reports that would have been important to mission planning if they had been more timely. When Smith commented that they were not the Office of Strategic Services and did not have the resources for such a program, Chennault responded that they had John Birch. He told them to send Birch out with some radios on a mission to set up a network of reliable Chinese agents who would pass intelligence regarding Japanese shipping back to him. Chennault realized that Japanese supply routes to Formosa were just off the coast and believed that his CATF could interdict shipping. When Smith informed Birch of the mission, Birch only had one question—could he preach in Chinese churches on Sunday? Smith responded that he could preach on Monday if he wanted, as long as he got the job done.

Birch left Kweiling and flew to the CATF’s easternmost airfield, from which he set out on foot. He hired a coolie to assist him with his cargo of radios and prepared to trek to his first destination in Fukien Province. He would have to cover more than 300 miles in Japanese-controlled territory, so he decided to disguise himself as Chinese. He dyed his brown hair black, then donned traditional Chinese peasant garb and put on sandals. His initial trek was over mountains, and as he climbed he taught the coolie an old children’s spiritual, “Climbing Jacob’s Ladder.”

After they descended the mountains and reached a river, Birch sent the coolie back home and obtained a sampan from a guerrilla. He repeated the process of using a coolie when trekking overland and sampans on rivers when he could, a system that allowed him to average nearly 40 miles a day. He kept in touch with Smith by radio. He frequently encountered Chinese Christians who were incredulous to see a missionary so deep inside Japanese territory, and he preached to several congregations as he came across them on his way to the coast. On one occasion he and his coolie hid their cargo in a dung pot and carried it through a Japanese checkpoint as the guards held their noses and turned away.

When he reached a village near the coast, Birch sought out a Christian he had been told to contact. The man took him to the leaders of the local church, where Birch explained his mission and told them he needed two fishermen who were “willing to risk their lives for China.” One of the deacons said he was a fisherman and that he had a friend who would help. Birch interrogated the two men to be sure they were dedicated to defeating the Japanese and then showed them how to work the radios. He also promised them $10 a month apiece to cover their expenses and compensate them for their time away from their livelihood. He gave them a radio and a codebook that was set up so they could translate their messages into English.

Birch devised his own system of mixing up the pages to confuse the Japanese who monitored the transmissions. Meanwhile, Captain Smith had set up monitoring/relay stations in Free China to pick up the messages from the coast and pass them along to his headquarters. By the time Birch returned to Free China, Smith was receiving as many as 50 messages a day.

The intelligence was priceless. The coast watchers transmitted reports of ship sightings that were relayed to CATF. Chennault set up a Teletype system at his main base to pass along mission orders to his dispersed bases. In some instances, CATF aircraft were in the air on their way to intercept Japanese ships within 10 minutes after the coast watcher transmitted the report. Some ships were attacked less than an hour after they were reported. Smith also compiled a daily report that was transmitted to Navy personnel at Stilwell’s headquarters in Chungking, which then transmitted the information to U.S. Navy submarines and ships operating in the China Sea. Chennault was elated at the quality of the intelligence and recommended Birch’s promotion to first lieutenant for the third time.

Although Arnold still considered him a crackpot, in early 1943 Chennault was allowed to break out from under Tenth Air Force control as the CATF became the Fourteenth Air Force. Chennault’s staff members were elevated in rank, and John Birch was promoted to first lieutenant while his immediate superior, Captain Smith, jumped two ranks to become a lieutenant colonel. Chennault was promised a force of 500 planes, and Stilwell was ordered to transfer control of the Hump airlift from Bissell to Chennault. Stilwell refused.

In the spring of 1943, Japan launched a new Chinese offensive, and Smith sent Birch to serve as a liaison between Fourteenth Air Force and Chinese Marshal Hsueh Yo’s army on the Yangtze River. Birch’s mission was to set up air support for the Chinese ground forces. He would seek out targets and guide air strikes in on them and set up a rescue network to retrieve downed airmen. It was a pioneer effort, and Smith and the Fourteenth Air Force staff hoped to establish tactics for a larger effort with new agents who would be trained to take his place.

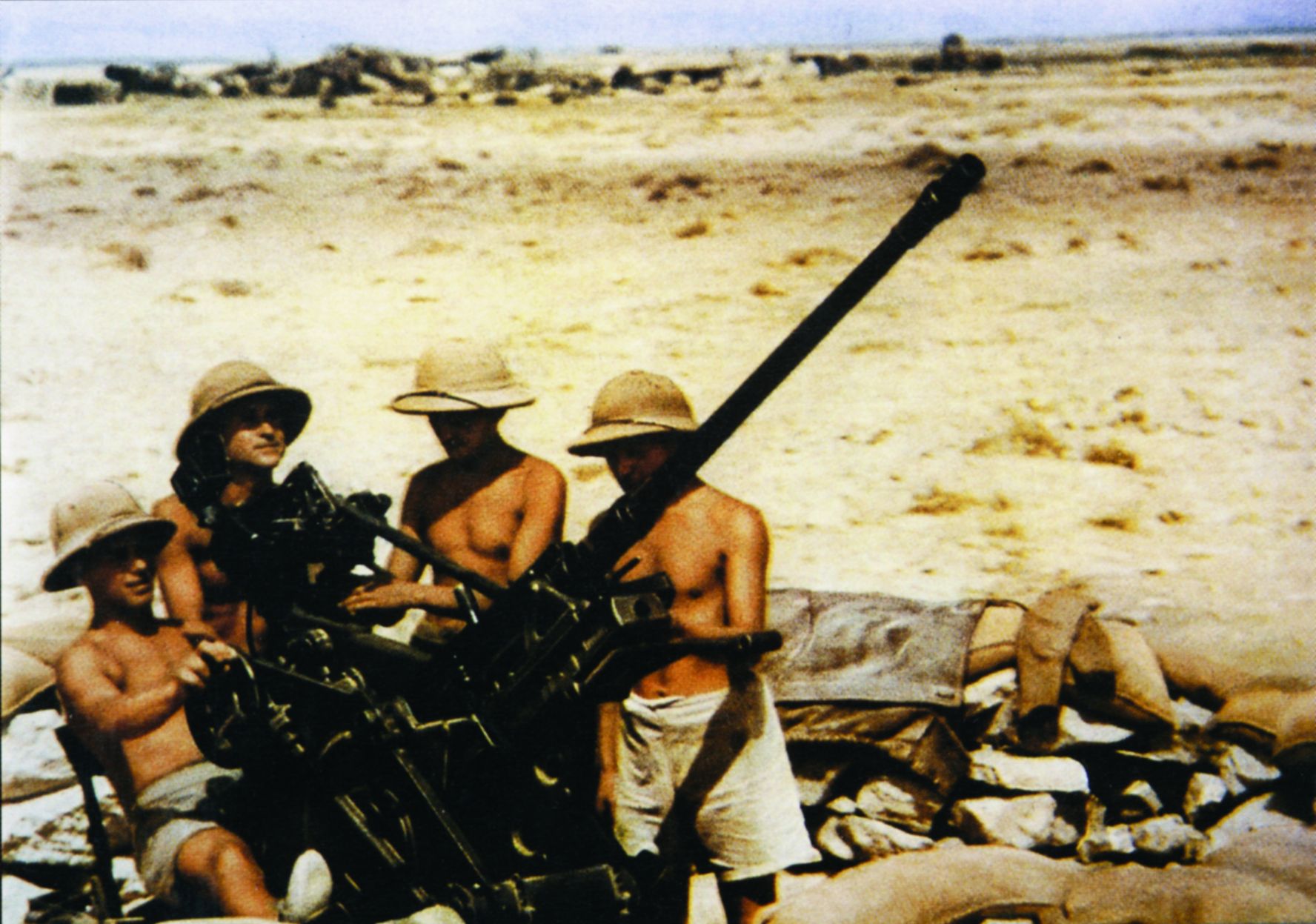

Birch went by train and sampan to Changsha, where Yo had his headquarters. After familiarizing himself with the area, he set out with a team of Chinese soldiers on a 300-mile hike to the front lines, where he was turned over to guerrillas who took him deep inside Japanese territory. Once again, he disguised himself as a coolie. He and Smith had worked out a plan under which Birch would mark targets with white cloth panels pointing in the direction of the target. His first target was a pagoda that had been converted into an ammunition dump.

A Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter came in for a strafing run that set off the ammunition. Then Birch directed the fighter onto a Japanese artillery piece. He and his guerrillas slipped back into the forest and crawled on their bellies in the darkness of night to locate their next target, a fuel dump at a Japanese camp. Early the next morning a pair of Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers hit the dump, causing fires that spread through the camp. Birch remained at the front for more than a month, calling in air strikes that enabled the Chinese troops to drive the Japanese back into their previous positions.

In mid-1943, Birch was summoned back to Kunming, where he was to take part in the commissioning of a new batch of intelligence agents, including his friend Arthur Hopkins, who had served briefly with him the year before, and Chennault’s former chaplain, Paul Frillman. Birch briefed the men on his experiences, and Williams pointed out that he was the first U.S. agent to live and work with Chinese troops. The commissioning of the new agents gave Birch the opportunity to ask Chennault for permission to apply for pilot training. He had been interested in aviation since childhood, and seeing the Fourteenth Air Force fighters and bombers in action at close range had rekindled his interest. Chennault agreed to pass the application forward but would later tell Birch that he was more valuable to him in his present capacity than 10 pilots would have been.

Birch’s next mission was to set up a network of agents along the Yangtze to keep watch on river shipping. Arthur Hopkins and Sergeant Leroy Eichenberry would assume his previous role with Marshall Yo. They would fly together to Changsha. Then, Birch was to continue northward to contact General Heuen Yoh, commander of the Second Guerrilla Brigade. Birch remained in Changsha for a few days before continuing his journey to visit members of the China Inland Mission and deliver supplies he had brought for them. Accompanied by two Chinese radio operators and a team of coolies, he then set off on a 10-day trek in scorching heat through swamps and over hills to link up with General Yoh. The guerrillas planned a route for Birch and his two radio operators down the Yangtze in a series of junks. Once again, Birch set up a system for rescuing downed airmen. While on the Yangtze, he learned that the Japanese were drawing considerable material from the iron mines at Shihweiayo and arranged an air strike against them.

Birch’s determination was revealed when he got wind of an ammunition dump at Hangkow that had been established in a former residential area. He infiltrated through Japanese positions and located the dump, then radioed directions back to the Fourteenth Air Force. The area was too congested to risk laying his customary white panels, and when the formation of bombers came over, the crews were unable to identify the target. Birch then made his way back to a remote landing strip where he was picked up by a light airplane and flown to the bomber base. He went up in the nose of the lead airplane and pointed out the target to the bombardier. The first bombs set off the dump, and the series of explosions spread through the Japanese camps. Guerrillas operating in the area reported that bodies of dead Japanese were hauled away by the truckload.

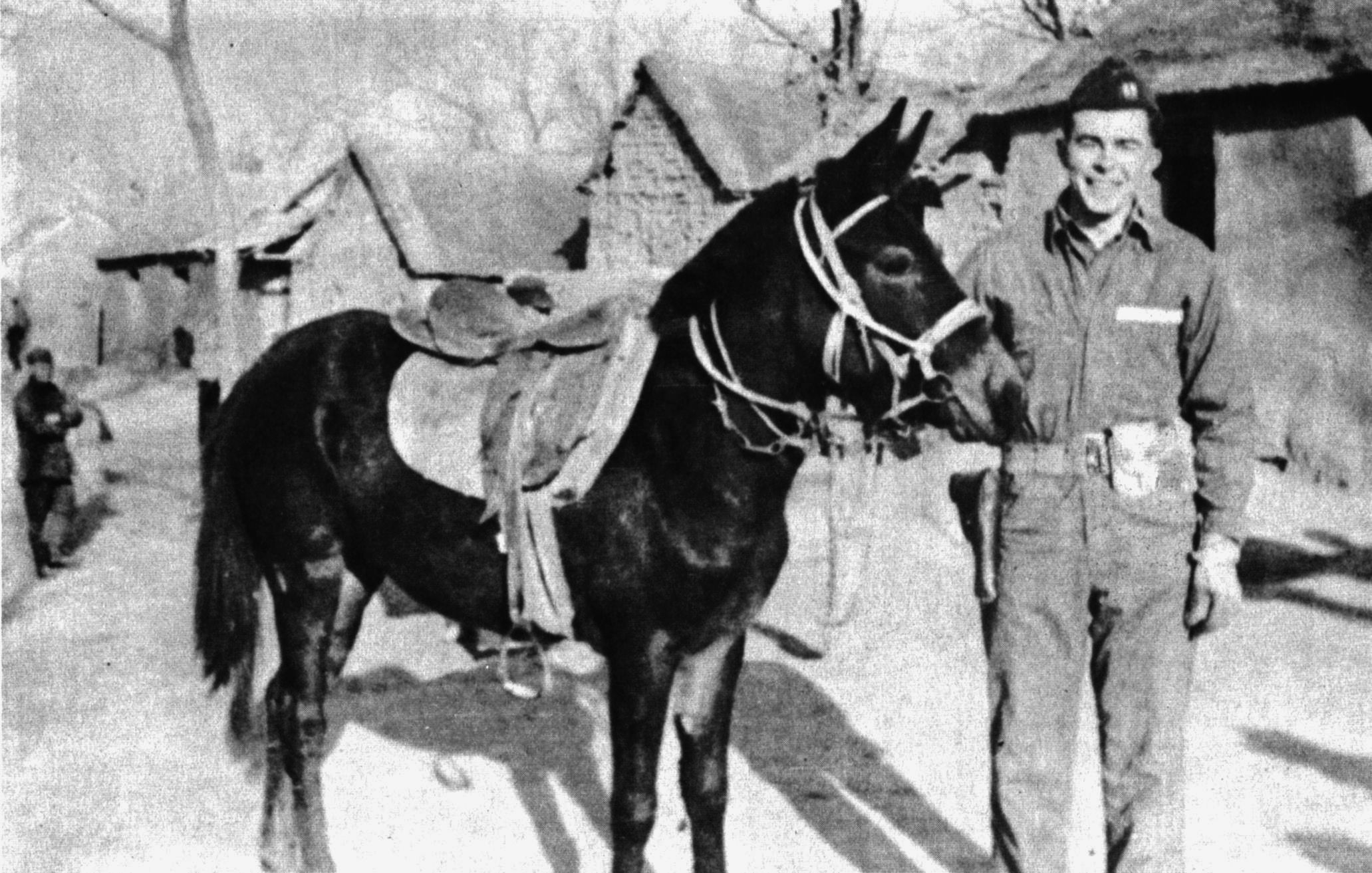

In the spring of 1944, Birch went on “a trip,” as he called his missions, to the plains of the Yellow River. There he found huge numbers of Japanese troops massing for an offensive. Riding on horseback, he set out to locate the enemy lines of supply. Birch saw thousands of Japanese marching southward from northern China. He wondered why Mao’s Communists had made no attempt to stop them. After setting up observation teams to keep watch on the railroad, he boarded a sampan for the journey down a tributary of the Yangtze to Lao Ho Kow, where he was to link up with two other members of the intelligence team.

On May 17, Birch joined Lieutenant William Drummond and Sergeant Eichenberry, then set out with them to search for a place to set up an intelligence base before proceeding north to Shantung Province to establish a network of Chinese agents. As they proceeded northward, they came into an almond-shaped valley on the Yellow River, which had been bypassed by the Japanese. An army of 100,000 Chinese soldiers had been cut off in the valley for over a year. Birch immediately recognized the 100-mile-long valley as a natural location for a forward base, with a radio station and secret airfields at each end. Birch visualized the airfields being used as emergency landing strips for airplanes returning from missions to the north and as refueling stops for bombers and fighters going on missions into Manchuria—and perhaps even Japan. They could also serve as gathering points for downed aircrews to be picked up by Fourteenth Air Force transports.

Birch radioed his headquarters for approval, then explained his idea to the Chinese general in command of the troops and received permission to go ahead. After setting up the radio station, Birch took a squad of Chinese soldiers looking for sites for airstrips. Relying on experience gained during a summer in which he measured cotton in Georgia, he laid out a 3,500-foot runway himself. Thousands of Chinese soldiers worked with picks and shovels to level out a dry streambed and then packed the runway with sand and gravel. With the airstrip complete, they constructed a small terminal and radio shack nearby. A second strip was laid out in a pasture. The first airplane into the valley came to evacuate Sergeant Eichenberry, who had come down with cholera. The two airfields were constructed entirely by Chinese military personnel and without any assistance whatsoever from U.S. sources other than Birch’s supervision. They had not cost the U.S. Army one thin dime.

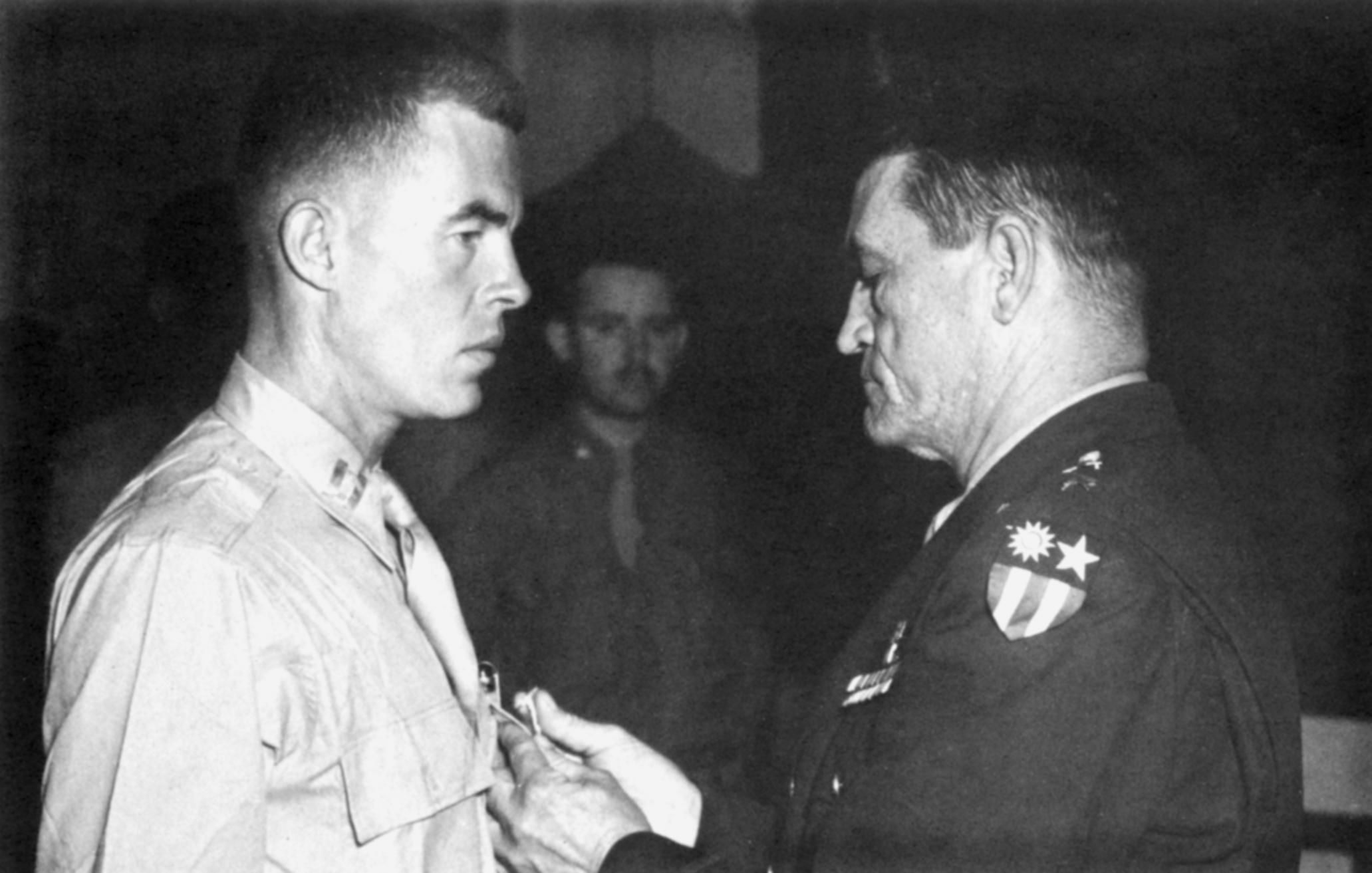

John Birch also suffered from serious medical maladies, particularly malaria, the same disease that had forced his father to leave India. In early August, he was picked up at one of the secret airfields and flown to Kunming to be decorated with the Legion of Merit.

Recognizing that Birch was ill and tired, Chennault told him to take a 60-day furlough and go home for a rest. Birch refused, telling his commanding general that he did not want to take up a slot that some other soldier could use. Birch was true to his word when it came to furlough. He never took leave the entire time he served in China, not even to visit a young Scottish Red Cross worker he met in China, but who transferred to India shortly after they met. Birch proposed marriage to the girl, but then retracted the proposal when he realized that his postwar plans were to take the gospel into either Tibet or Turkestan, remote areas that would make life rough on a woman. The woman remained single for the rest of her life.

A Japanese offensive in mid-1944 cost the Allies considerable territory in eastern China, a defeat that Chennault and many others blamed on Stilwell’s obsession with Burma and neglect of China. Stilwell’s days in China were numbered, although he attempted to gain complete control over the theater. He is believed to have drafted a plan giving him command of all the Chinese armies and sent it to Washington, where it was presented to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. When a message came back ordering Chiang to turn command over to Stilwell, “Vinegar Joe” made the mistake of delivering the message himself—“to break the Peanut’s face” as he expressed his feelings in his diary. The plan backfired. Although Chiang had been willing to relinquish command, Stilwell’s arrogance not only caused him to change his mind, but he also wired Washington that he was through with Stilwell and demanded that he be replaced.

The arrival of General Albert C. Wedemeyer brought about a change in the fortunes of the Fourteenth Air Force. Chennault began receiving support that Stilwell had withheld, and Fourteenth Air Force returned to offensive operations throughout the country, striking targets in northern China and south into Indochina. Chennault supported Birch’s plan to use the new base on the Yellow River for intelligence operations in north China and ordered the delivery of supplies to the airfield at Anhwei.

Birch returned to duty and went north with the supplies. Shortly after he got there, he took a squad of Chinese soldiers and radios and headed further north. As was his practice, he carried a New Testament and a supply of gospel tracts. He was gone for two weeks. In early November, the effort paid off. One of the new agents radioed that he had discovered the crew of a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, who had bailed out of their airplane six months before and had been hiding in the mountains. Guerrillas brought the men to the new base, and they were flown out in a C-47. On the day the transport came, an intense thunderstorm struck the valley and the airplane arrived in the middle of a heavy downpour. Birch ran out to the radio shack and got a bearing on the airplane, then talked the pilot in for a landing in nearly zero visibility.

In early 1945, Birch arranged the evacuation of a number of missionaries who had been ministering in northern China. Mostly elderly, they were American, British, and Dutch who had ministered in rural towns that had been bypassed by the Japanese. As the war intensified, they began to fear for their lives. Some of those in the Anhwei area got wind of Birch’s base and sent word through guerrillas that they wanted to be rescued. Birch advised them to come out of the mountains and that he would evacuate them somehow. Several stranded airmen were also in the valley waiting for a plane.

In late December, the missionaries began arriving. Birch called Kunming but learned that Colonel Smith had been called back to the United States for an urgent meeting. No one else in Kunming was sympathetic to the missionaries’ plight. Birch was told that they were not running an airline for missionaries. There were not enough downed airmen to justify sending a transport, and even when Birch sent word that they were running out of supplies, he was told he would have to wait.

Birch finally got Kunming’s attention when he told them that he had a bag of sensitive intelligence that needed to be sent back. He was finally promised that an airplane would arrive when the weather broke. Birch rode a pony the 50 miles to the airstrip and discovered a snow-covered runway. He went to General Wang, the Chinese commander, and told him he needed men with shovels. Wang asked how many, and Birch said about 800 would do. The Chinese soldiers quickly cleared the runway, and the plane came in and picked up the stranded airmen and all but one of the missionaries, who had to wait for another month. The pilot gave Birch what he considered to be distressing news. Birch and his men were going to be transferred to the OSS, which was why Colonel Smith had been called to Washington.

This was something Birch had feared. A planeload of OSS colonels and majors had arrived at Kunming before he left and started throwing their weight around. A few days after the pilot told him of the rumor of the impending transfer, Birch received a message sent under Chennault’s name that he and the other Fourteenth Air Force intelligence men would be transferring to the OSS and that the move would be beneficial for them. Birch was not buying it. He was convinced that the OSS would cause nothing but problems and that they would mess up the entire intelligence program he and the agents who followed him had been working for years to set up and maintain. He sent a return message in which he said he would rather be a Fourteenth Air Force buck private than a full colonel in the OSS and have access to Wild Bill Donovan’s slush fund, knowing that the message would be intercepted and read by every OSS man in China.

Birch’s opinion of the OSS changed when Lieutenant Bill Miller, a recent West Point graduate, came to visit him at Ankang where he had been hospitalized during another bout with malaria. The young officer told Birch that he was famous in the OSS and that everyone back in Washington had heard about him. Birch replied that it was probably because of the message he had sent. Miller confirmed that he knew about it but that Birch was widely respected for the magnificent job he had been doing in China for the past three years. He told Birch that he had been assigned as an escape and evasion agent to the airfield at Foyuang about 50 miles from Birch’s base at Linchuan. Deciding he liked Miller, Birch offered to help him all he could.

When Smith returned from Washington, he brought Birch back to Kunming to attempt to talk him into accepting the transfer to the OSS. Birch was adamant in his refusal and insisted on remaining with the Fourteenth Air Force. Smith was not surprised. The rest of his staff had also been opposed to the transfer, but he had managed to talk all of them into accepting it. All, that is, except Birch. Chennault himself joined in the effort to convince Birch to accept the transfer, but the officer, who had been promoted to captain, remained obstinate. They finally worked out a compromise. Birch would work for and with the OSS but would remain on the Fourteenth Air Force roster. Chennault attempted once again to convince him to take a furlough in India, and Birch was tempted since it would offer him an opportunity to spend time with his former fiancée. Birch told Chennault that the war was almost over, and he intended to stay until “the last Jap is out of China.”

Birch was now a captain, and the Chinese had given him a name, Bey Shang We, which literally meant Birch Captain. Although his activities were classified, John Birch was well known throughout China, especially among the Chinese military and the Christian community. He was also known to the Communists, who occupied a mountainous region in northern China and had done very little to oppose the Japanese. Birch was a strong anti-Communist and had been before he came to China. When he got there, he learned from the veteran missionaries that the Communists were considered to be more of a menace than the Japanese.

After three years in China, Birch had come to believe that Mao and his Communists were merely waiting for the Allies to defeat the Japanese, and were depending on combat to wear down the Nationalist forces so that they would be unable to resist a Communist takeover after the war. Birch was not one who kept his views to himself and frequently admonished his friends and associates of what he believed were Communist intentions—to take over China, then move into Korea.

Birch had been in the war since the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, first as a missionary wandering through remote regions and existing on starvation rations, then as an intelligence officer operating in enemy territory. He was emotionally if not physiclly worn out, and was tired of the war. He also felt that he, like Chennault, was being shoved aside. He had discovered the Anhwei pocket and set up operations there, but now there were three bases in the area he had pioneered and he had been made subordinate to an OSS major. When he got word that his family was thinking about selling the farm he had worked so hard to establish, he became even more morose. He wrote an essay reflecting his emotions entitled “The War Weary Farmer.”

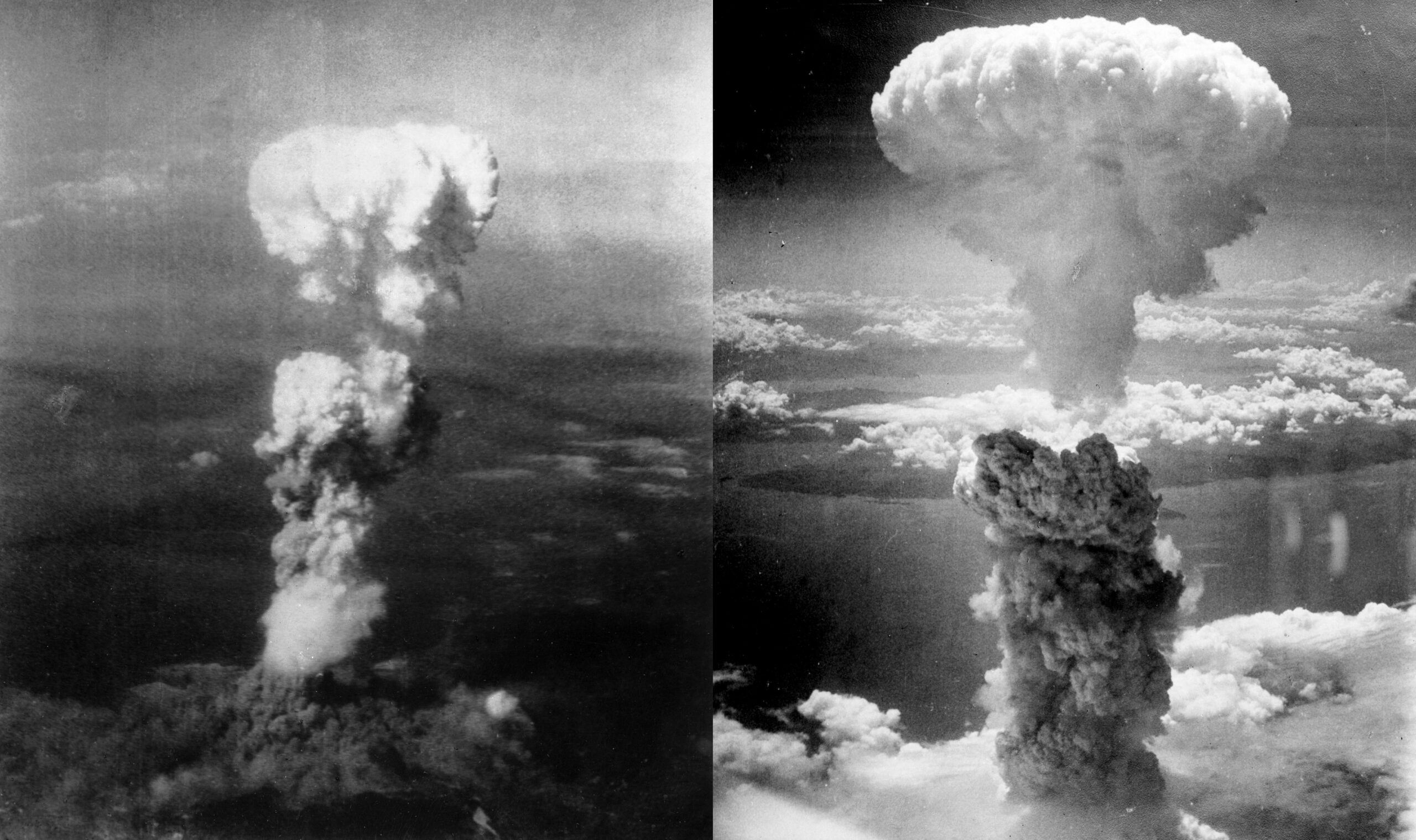

Birch’s intelligence network brought news of Communist activities in northern China and Manchuria. Chinese Communist troops were occupying territory that had been abandoned by the Japanese, who were in full retreat now that the end of the war was near. Communists in Henan Province tore up dikes that held back the Yellow River, causing flooding in the Anhwei pocket that destroyed what had promised to be a bumper crop. Birch was at his base at Linchuan when he got word of the detonation of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima. He also received orders telling him to make preparations to move north into Japanese territory to accept the surrender of Japanese garrisons.

Immediately after the Japanese surrender announcement, Mao’s Communists came out of the hills where they had been hiding and moved into Japanese territory as quickly as possible before American and Nationalist forces could come in. Their intention was to capture arms and ammunition and disrupt Allied lines of communications. General Wedemeyer ordered OSS offices in China to make plans to get their agents to Japanese installations as quickly as possible to make arrangements for surrender to the proper authorities. Birch and his friend Bill Miller were ordered to Süchow. Miller made plans to go by junk and suggested that Birch and his party go with him, but Birch replied that it was too risky and that he hoped to get a plane. The two talked openly in their regular morning radio conversation since the war was over and they felt no need to speak in code.

The plane did not come through so Birch made plans to hike overland to Kweiteh and catch the east train on the Lunghai railroad. His friend and fellow agent Captain Jim Hart warned him that the Communists might already be in control of the railroad and suggested he go with Miller instead. Hart later reported that Birch went into a tirade about how the Antichrist would soon take control of the world and that Communists were his servants.

The following morning Birch and his party departed. Three other Americans—Lieutenant Laird Ogle, Sergeant Albert Meyers, and Albert Grimes, a civilian OSS operative—five Chinese officers, and two Japanese-speaking Koreans along with Birch made up the party. One of the Chinese, Lieutenant Tung Fu Kuan, was assigned as Birch’s aide. When they arrived at Kweiteh, they were joined by two Chinese who had collaborated with the Japanese, a general and his orderly. The general was to escort them to his counterpart in Süchow, where they would accept the Japanese surrender. A Japanese officer received the party at Kweiteh and assured them they would be well received at Süchow, but that there were Communist guerrillas along the railroad to the east.

Forty-five miles down the railroad the train halted at the station at Tangshan. The Japanese stationmaster informed the Korean interpreters that the railroad had been sabotaged up the line and that Communists, Japanese, and Chinese puppet troops were fighting in the area. The train was going to remain in the town until the rails had been repaired and the fighting ended. Birch and his party discussed their options. Ogle proposed that the four Americans go on alone. Birch decided they would all go and commandeered the locomotive and a baggage car. After only 10 miles, the locomotive came to a halt when the engineer saw that the rails ahead had been removed. Ogle and Birch went into a village to hire coolies but learned that Communists had come in the night before and killed most of the men. A Japanese work crew arrived with new rails. Birch commandeered the handcar and told the Japanese commander to have his men move it over the break.

After spending the night in a village about a mile down the tracks, Birch and his party got under way again early the next morning, with each man taking turns pumping the handcar in the hot China sun. Sometime before noon they ran into a group of about 300 Communists, all carrying arms. The Americans and Chinese were all in uniform, and Birch wore the well-known Flying Tiger insignia of the Fourteenth Air Force on his arm. There was little doubt who they were. Birch took Lieutenant Tung ahead of the party to meet the Communists, identifying himself as Captain John Birch of the American intelligence services on a mission under the orders of General Wedemeyer. He asked to be taken to their “responsible man.”

One of the Communists said he would take them to their leader, but they must first disarm. Birch refused, responding that the Americans and Chinese were allies and must respect each other. The Communist argued for a time, then gave in and took Birch to a man he identified as their commanding officer. The officer demanded that he be allowed to examine the men’s equipment, and Birch refused, replying that their equipment was the property of the U.S. government and not for personal use. He advised the Communist that the United States dealt harshly with thieves and demanded that they be allowed on their way.

Over the next few hours the party encountered several groups of Chinese Communists but managed to make its way through them. Birch griped constantly about the Communists, referring to them as nothing but common thieves and bandits. His men realized he was agitated and feared for their lives. When a pair of North American P-51 Mustang fighters flew over at low altitude, they attempted to signal them, but without success.

Lieutenant Tung proceeded ahead of the party to deal with the Communists. When they reached the town of Hwang Kao, Tung entered the railroad station and found it occupied by hostile-looking Chinese. He advised them that they were on a mission to Süchow for General Wedemeyer and asked to speak to their “responsible man.” When one of the Communists blurted out that they must disarm the Americans, Tung replied that if they attempted to do so it would cause a serious misunderstanding. The senior officer told Tung he would send someone with him back to the party, but Tung heard him advise the man to take his gun along and if anything happened to shoot Tung first.

By this time, Birch was thoroughly incensed at the treatment he and his men were receiving from their reputed allies. When Tung and the Communist joined the party, he asked the Communist if he was “another bandit.” General Peng, the Chinese collaborator, and Albert Grimes advised Birch to take it easy. When Tung told Birch that the Communists intended to disarm them, Birch exploded, blurting out that Americans had liberated the entire world, but now the Communists wanted to disarm him and his men! The Communist told Birch that he was not the “responsible man” but that he would take them to him, but that since they refused to disarm, he would not be responsible for anything that happened. Tung later reported that he and Birch expected the Communists to let them pass, then shoot them in the back.

Finally, a Communist wearing the Sam Browne belt that identified him as an officer told Birch that he could see their responsible man. Ogle and Grimes insisted that they go along, but Birch told them to wait with the rest of the party and he and Tung would proceed alone. Tung later reported that Birch told him that he wanted to see how the Communists were going to treat Americans and that he did not care whether they killed him. If they did, America would punish them with atom bombs. At one point Birch grabbed their guide by his collar and said, “What are you people? If I say bandits, you don’t look like bandits. You are worse than bandits.” Tung told the Communists that Birch was joking.

A little later someone called out, “Look, here is our leader.” Birch and Tung turned and saw that they were referring to the man in the Sam Browne belt. The officer told his men to load their guns and disarm Birch. Tung had taken off his sidearm earlier and told the Communists to let him get Birch’s gun in order to avoid “a serious misunderstanding.” The officer ordered one of his men to shoot Tung, which he did. He then told a soldier to shoot the American. The Communist hesitated, then fired a shot into Birch’s leg. Shortly afterward, Tung passed out from loss of blood. When he woke up, he was lying in a ditch next to Birch’s lifeless body.

Word of John Birch’s death soon reached other OSS operatives. When Bill Miller arrived in Süchow, he was informed that Communists had killed his friend. Japanese soldiers and friendly Chinese found Tung and Birch’s bodies and took them to Süchow, where Tung was hospitalized. Both Tung and Birch had been badly beaten, and an autopsy found evidence that after Birch had been shot in the leg, he had been bound and then shot in the back of the head. His face had been slashed beyond recognition by bayonets. Miller was able to identify the body by Birch’s general build and from photographs taken when it was found.

The senior Japanese officer at Süchow had refused to surrender to the Communists and waited for someone from the Nationalists to arrive in the city. He was sympathetic to Miller for the loss of his friend and offered his services to conduct an appropriate military funeral. Miller, the Japanese, Chinese puppet officers, and Jesuit missionaries who were in the city planned the funeral together. Two other Americans, pilots who had been killed in a crash near the city, would be interred along with Birch. A Catholic high mass was held for the young fundamentalist Baptist, and after the mass the entourage of Japanese and Chinese officers and Jesuits led a procession through the city to the music of a Japanese military band. The coffins were carried by 24 coolies. The three bodies were interred in a plot on the side of a mountain just outside the city. A Chinese Protestant conducted a graveside service. Japanese soldiers fired the traditional volley as the bodies were lowered into their graves.

Frequent contributor Sam McGowan is a pilot and resident of the Houston, Texas, area. He has written extensively on World War II in the China-Burma-India Theater..

Thank you for this. I grew up with stories of the AVG\CNAC Hump pilots, my father was CNAC Hump Pilot. I have learned so much today reading this. Peggy Maher

I first learned of the John Birch Society as a young boy. But, I just learned of the life of this man who accomplished so much during his short life. God received him into His Kingdom whith a warm “well done”, I am certain.