By Patrick J. Chaisson

At the start of World War II, Japanese airpower ruled the skies over China and the Pacific. Japan’s modern, highly maneuverable fighters, flown by well-trained and combat-tested pilots, outperformed anything the Chinese, British, or Americans could get airborne to oppose them.

When the Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 naval fighter first appeared over China in 1941, Allied aviators were astonished. Not only was the Zero more agile than anything they had ever seen, but its speed and heavy armament guaranteed almost certain victory in a dogfight. Quickly this new airplane earned a terrifying reputation for flying circles around the Hawker Hurricane or Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk.

Few Westerners realized at the time that most of these so-called Zeros were actually Nakajima-designed Japanese Army Air Force (JAAF) aircraft. Known as the “Army Zero” and later code-named “Oscar,” the Ki-43 Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon) became the JAAF’s most important fighter of World War II.

The Hayabusa served throughout the Pacific War, undergoing several design upgrades to improve performance, protection, and firepower. Some 5,919 were built, more than any other Japanese aircraft except the Zero. Almost all the JAAF’s top aces scored kills with this nimble little fighter, a capable workhorse in skilled hands right up to war’s end.

A Reliance on Speed and Agility

In 1937, a Nakajima design team headed by Hideo Itokawa began work on a successor to its Ki-27 fighter, known as the Type 97. The Japanese Army required a lightweight, maneuverable air superiority fighter that would clear the skies of enemy aircraft so ground forces could operate unimpeded. The Ki-27 met this requirement but was already getting long in the tooth compared to Anglo-American aircraft then in development.

Itokawa’s engineers set out to design a fast, modern interceptor possessing superb maneuverability. The low-wing, single seat Ki-43 would feature all metal construction, a streamlined canopy, retractable landing gear, and a 950-horsepower Sakae radial engine propelling it to over 300 miles per hour. To meet JAAF weight specifications, Nakajima designers chose to omit armor protection and self-sealing fuel tanks. Pilots would rely on the machine’s speed and agility to close with an enemy, finishing the job with two Type 89 7.7mm machine guns.

Yet, when the Ki-43 prototype first flew in January 1939, it performed poorly. Test pilots complained the Nakajima design was unresponsive, sluggish, and not much faster than the Ki-27 it was intended to replace. Clearly, Itokawa’s design needed work.

It took Nakajima 18 months and 13 separate modifications to deliver an acceptable aircraft. Engineers trimmed every ounce of extra weight from the Ki-43, as well as increasing wing area and redesigning the canopy. They also installed a set of paddle-shaped “butterfly flaps” under the wing roots to boost maneuverability.

The newly modified interceptor performed wonderfully. It could reach an altitude of 38,500 feet with a 3,900 feet per minute rate of climb. Maximum speed was 308 miles per hour at 13,000 feet. Its butterfly flaps enabled the Hayabusa to turn inside any aircraft then flying, even the Zero.

The Nakajima Ki-43-I Sees Production

Nakajima’s Ki-43-I, as the modified design became known, measured 28 feet, 11 inches long, with a wingspan of 37 feet, six inches. It weighed 3,483 pounds empty and 4,515 pounds combat loaded. Armament was initially two 7.7mm machine guns in the front cowling, later replaced by one or two heavier Ho-103 12.7mm aircraft cannon as those weapons entered service.

Full-scale production of the Peregrine Falcon began in April 1941. The JAAF accepted it as the Army Type One interceptor, and Ki-43-equipped squadrons entered service in October. Before long the Hayabusa was battling P-40s of the legendary Flying Tigers and British-flown Brewster Buffalo fighters over Burma.

As war spread across Asia and the Pacific, Allied fliers learned to fear Japan’s angry little falcon. Tangling with a Ki-43 usually resulted in fiery death, so air tacticians such as General Claire L. Chennault of the Flying Tigers taught their pilots to avoid dogfighting with one at any cost.

It took time, however, for Chennault’s lessons to take hold. For the first year of the war Hayabusa aces such as Warrant Officer Iwataro Hazawa (15 kills) and Lieutenant Guichi Sumino (27 victories) racked up impressive scores against their Hawker-, Brewster-, and Curtiss-equipped adversaries.

On December 22, 1941, a flight of 18 Ki-43s encountered 13 Australian Brewster Buffalo fighters over Malaysia. Sergeant Yoshito Yasuda described his role in this air battle: “Luckily, Capt. [Katsumi] Anma found a fleeing Buffalo and attacked it from above and behind. My turn came when Anma’s guns jammed. I sent a burst into the Buffalo’s engine and saw it belch white smoke.” Hayabusa pilots claimed 11 kills that day for the loss of one Japanese plane; Australian records indicate three Brewsters were actually destroyed while two more made it home too badly damaged to repair.

Performance Issues of the Ki-43-I

Despite these early successes, JAAF aviators found fault with the Peregrine Falcon’s performance, firepower, and durability. In service the Ki-43 developed a fatal tendency to shed its wings during a steep dive. This was a direct consequence of Nakajima’s earlier weight saving modifications, and headquarters suspended all flight operations until strengthened wing spars could be installed.

Pilots also disliked the slow-firing Ho-103 cannon. A Japanese copy of the U.S. Browning M2 .50-caliber machine gun, early models often jammed in combat. The Ho-103’s unreliability forced most pilots to keep one 7.7mm machine gun installed as a backup.

Nakajima designers watched with concern as modern Allied fighters like the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and Vought F4U Corsair took to the skies starting in late 1942. They began work to upgrade the Hayabusa, adding a more powerful 1,150-horsepower engine, self-sealing fuel tanks, and armor protection for the pilot. A reflector gunsight was also installed, and the Ho-103’s reliability problems were fixed. Subsequent modifications included bomb/drop tank racks, radio equipment, and clipped wings intended to improve the roll rate.

The Ki-43-II Against Allied Bombers

The updated Ki-43-II was faster, stronger, and no less maneuverable than older models. Remaining uncorrected, however, was the Peregrine Falcon’s alarming vulnerability to enemy gunfire. Allied fliers soon discovered that one burst of .50-caliber machine-gun bullets into the Ki-43’s unprotected oxygen tank would usually cause a catastrophic explosion.

The Hayabusa’s two-gun battery was one-third as potent as the six heavy weapons carried by most American fighters. Even firing explosive shells, the Ho-103 cannon proved woefully inadequate against tough-skinned Allied warplanes. When Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers began operating in Chinese airspace in late 1942, JAAF fliers had no choice but to attack them with their poorly armed Falcons.

It took great courage to intercept the formidable B-24s, and even greater luck to bring one down. Captain Yasuhiko Kuroe told his pilots to fly head-on into the American formations and concentrate on a single bomber. “Attack boldly,” Kuroe counseled. “Go into the wall of fire and take their bullets, be relentless.” Kuroe’s tactic worked, but often at great loss to the fragile Ki-43s.

The tables were turning for those brave aviators forced to fly this increasingly obsolescent fighter. Twelve-kill JAAF ace Captain Yohei Hinoki observed: “By the time the Hayabusa had become a good attack aircraft things were changing. It was now to be used for defense … so again its firepower was insufficient. The Hayabusa was coming to the end of its time.”

Japanese Army Air Force pilots continued to operate the aging Ki-43 simply because that was all they had. While JAAF-flown Hayabusas fought desperately against superior Allied fighters, development of more advanced aircraft like the Ki-84 Hayate remained a low priority. Perhaps the government believed its own propaganda; in 1942 only good war news reached the Japanese people.

Countering the Ki-43

Those fighting over China and the Pacific knew better. American aviators were learning how to cope with the Nakajima fighter, now code-named “Oscar.” Using team tactics, well-trained U.S. Navy and Army Air Corps fighter aces began scoring heavily against the diminishing number of skilled Hayabusa pilots.

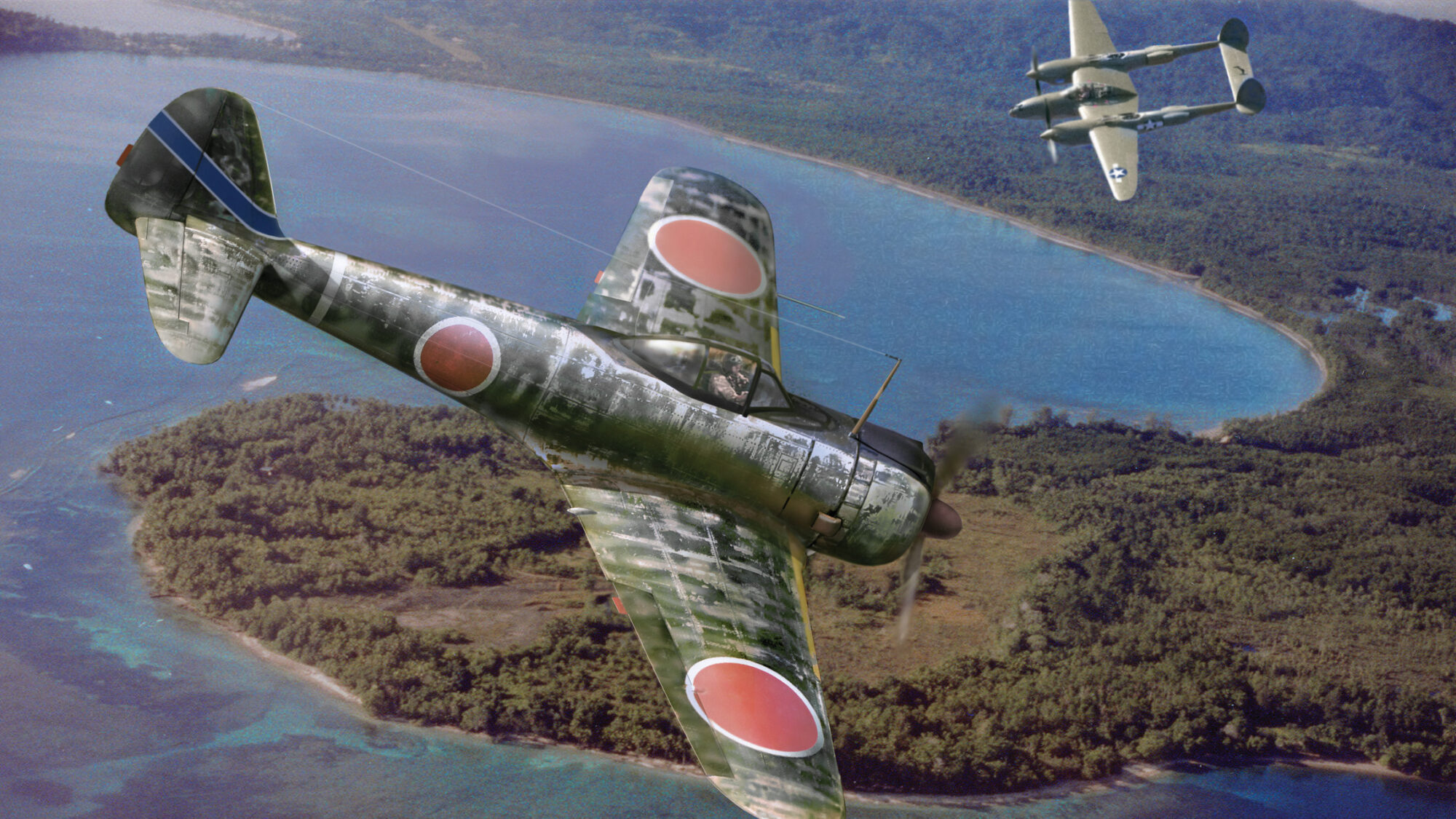

On August 2, 1943, Captain James A. Watkins and 15 pilots of the USAAF’s 9th Fighter Squadron pounced on a large formation of Ki-43s over the Huon Gulf in New Guinea. Flying the powerful P-38 Lightning, Watkins quickly destroyed two Ki-43s before diving on a third Oscar that was running away at wave-top level. Trying to outturn Watkins’s plane, the Ki-43 accidentally dipped a wing into the water and cartwheeled into a thousand pieces. This splasher was Watkins’s 11th career kill, seven of which were Hayabusas.

U.S. Navy aviators also encountered the Peregrine Falcon in combat. Lieutenant Ralph Rosen, piloting a Grumman F6F Hellcat from the aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill, recounted how he shot down one Ki-43 on October 12, 1944: “An Oscar passed almost in front of me in a steep dive, apparently going for some F6Fs below. The Jap pilot apparently did not see our section, and I managed to get on the Oscar’s tail. After a short burst, the wing root exploded and then the whole plane caught on fire and went down.” This victory was one of three Hayabusas Rosen would claim over Formosa that day.

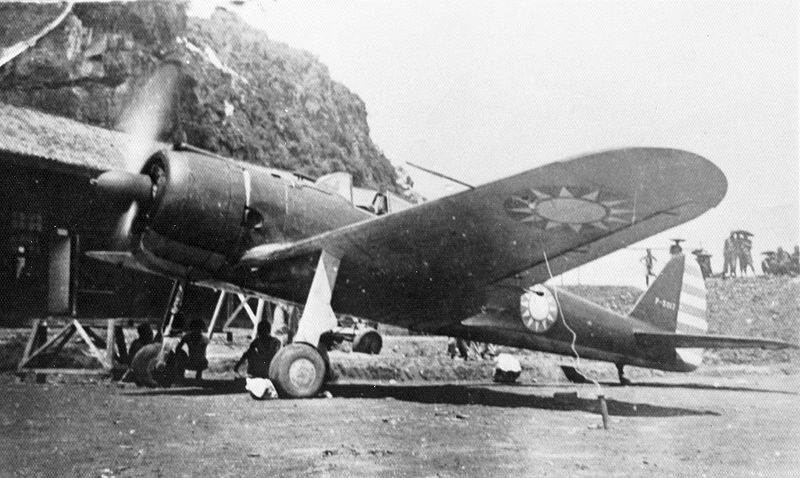

being prepared for a mission. The pilots are in their cockpits and ready for takeoff.

The Late Ki-43-III

By mid-1944, the Ki-43 was hopelessly outclassed as a fighter interceptor. This did not stop Nakajima from fitting it with an uprated 1,230-horsepower engine and twin 20mm cannons in a desperate attempt to again improve performance. The Ki-43-III was a case of too little, too late—for now there was a fearsome new threat making its presence known over Japan.

When Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers began flying combat operations, most surviving Ki-43s were withdrawn to the home islands. There they served in an air defense capacity, occasionally downing an American bomber despite the Hayabusa’s deficiencies in speed, protection, and armament. Often, fliers chose to ram their targets, a tactic usually fatal to both the Falcon and the B-29.

Other Hayabusas rammed Allied warships in their final role as kamikaze planes during the war’s last months. Those remaining soldiered on to the bitter end. After VJ-Day, captured Ki-43s continued to fly for several years in Chinese, North Korean, and Indonesian service. One Indochina-based French air squadron even briefly operated a few leftover Hayabusas against Viet Minh rebels.

Its sleek lines and impressive handling characteristics endeared the Ki-43 Hayabusa to its pilots but masked many serious flaws. An obsolete design, this workhorse could not compete against the increasingly more capable opponents it faced in combat. In the end, Japan’s angry little Falcon and the daring men who flew it were simply overwhelmed by superior Allied production, training, and technology.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments