By David A. Norris

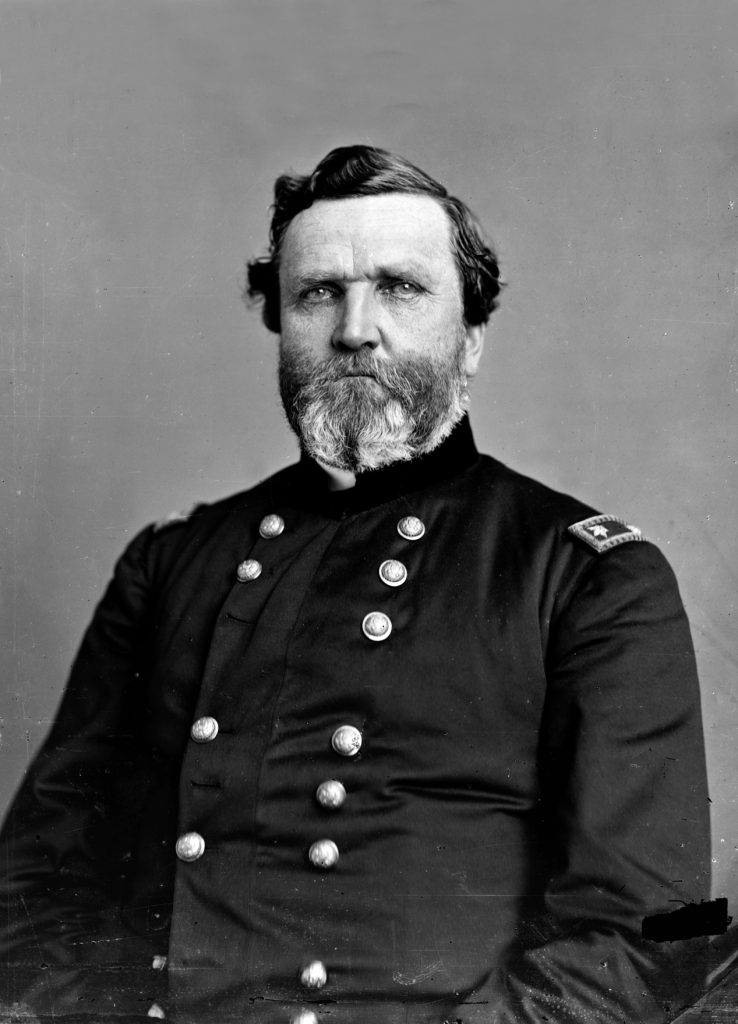

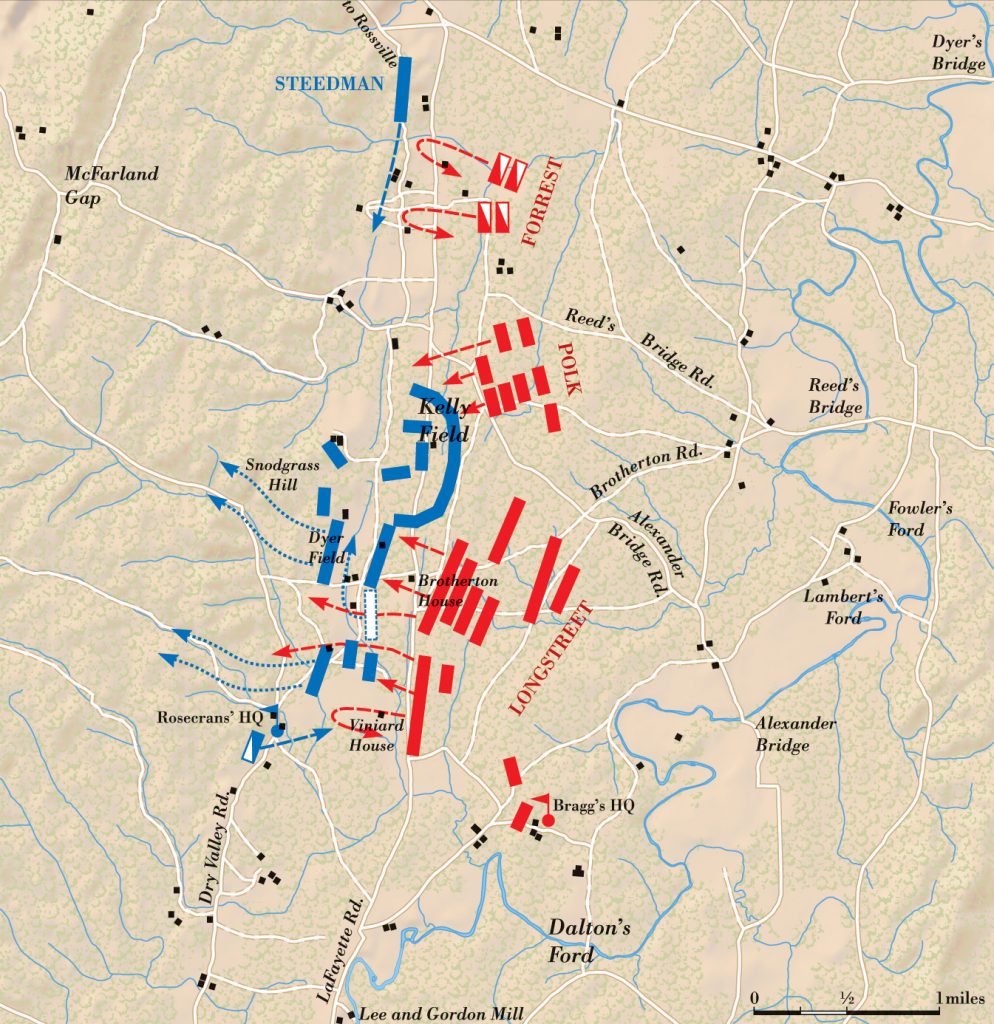

Amid the fog of powder smoke in the north-Georgia forest, the frayed remnants of the Union’s Army of the Cumberland faced determined Confederate troops who sensed an impending victory. In one of the most disastrous days to befall Union troops west of the Appalachian Mountains, an ill-fated order from Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans had led to the quick rout of half of his army on September 20, 1863. What remained of the Army of the Cumberland on the battlefield of Chickamauga was led by Virginia-born Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, the commander of one of Rosecrans’ three corps.

Threatened by two corps of Confederate troops, now perhaps twice in number to his XIV Corps, Thomas anxiously pondered reports of fresh troops approaching from the north. Were they the Union’s reserve brigades? If not, they might be those of Confederate cavalry officer Brig. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest, seeking to cut off the escape of Thomas’ embattled army. Thomas waited apprehensively to see whether the approaching troops were Union or Confederate.

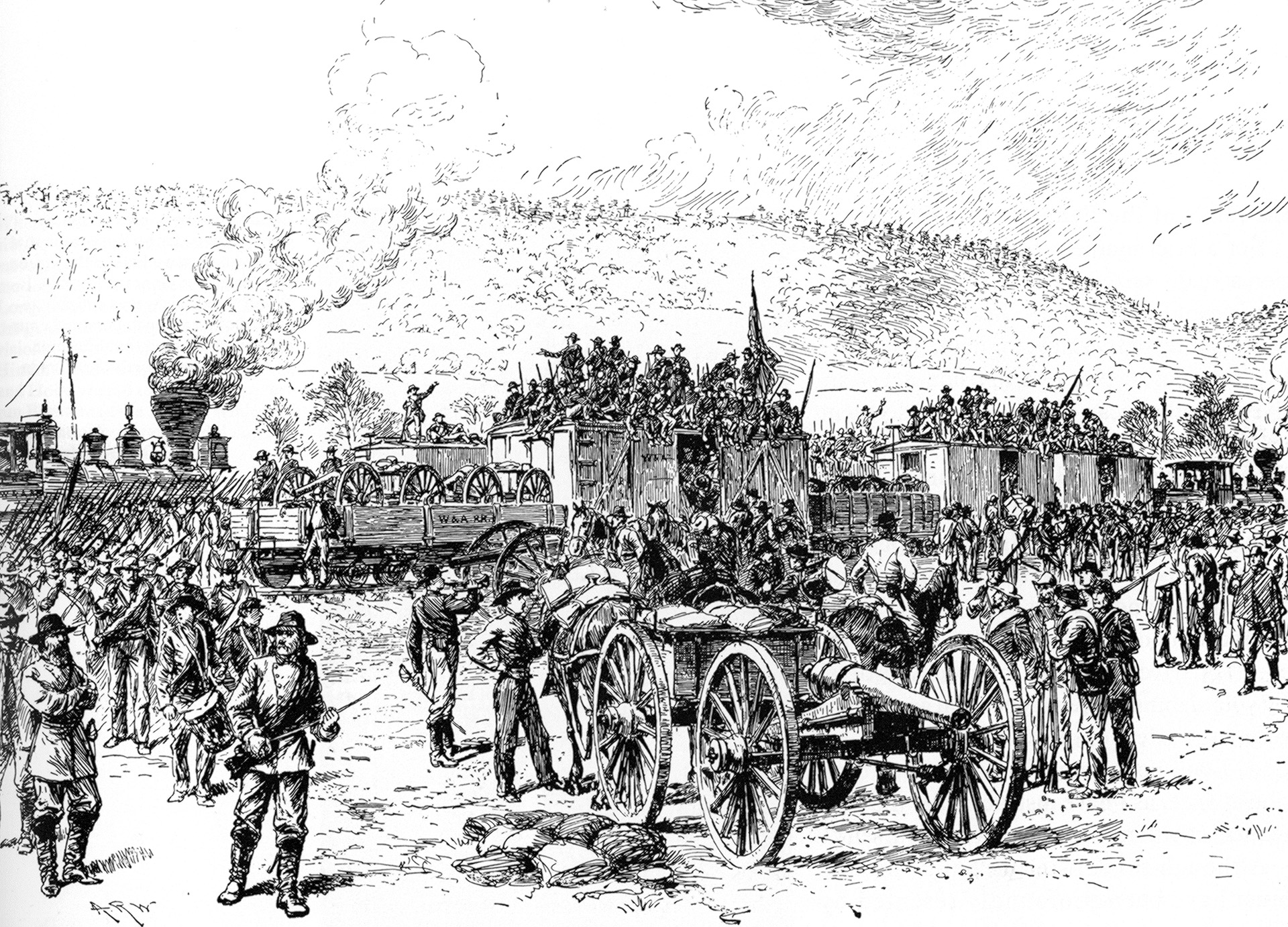

Although the Battle of Gettysburg in early July 1863 dashed Confederate hopes for a successful invasion of Pennsylvania, the pause in the campaigns in the Virginia Theater offered an opportunity for two divisions under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet from the Army of Northern Virginia to travel by rail to reinforce the Army of Tennessee.

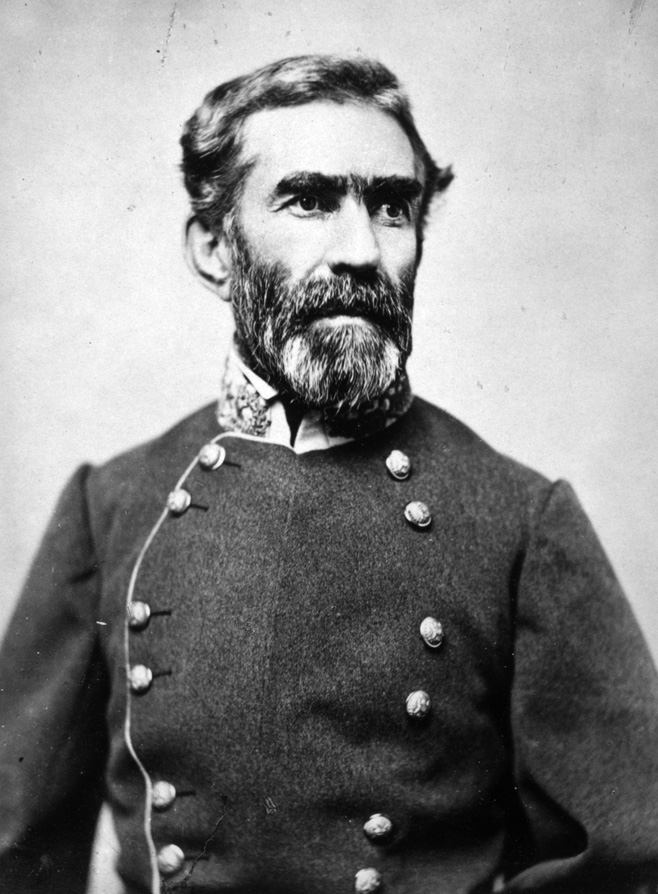

The Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by General Braxton Bragg, was struggling with little success to hold the state of Tennessee. Earlier in the war, Union control of the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers allowed Northern gunboats to shield army moves and protect steam transports ferrying troops and supplies. By mid-1863, Tennessee’s secessionist western and central regions were mostly under Union control, while the Confederates kept a shaky grip on the mountainous eastern part of the state. In eastern Tennessee, pro-Union sentiment was strong, spurring enlistments in loyalist Federal regiments and stirring up guerilla warfare.

Further complicating the Confederacy’s efforts in Tennessee was Richmond’s choice of army commander. Bragg, who was born in 1817 in Warrenton, North Carolina, graduated from West Point in 1837. He was a competent administrator who toiled to keep his men fed and supplied. Although he could not help being unlucky against superior Federal forces, he did himself no good with his prickly and quarrelsome demeanor. His generals came not only to dislike him personally, but also to hold him in such contempt as to openly disobey his orders and secretly conspire to trigger his dismissal by the Confederate States War Department in Richmond, Virginia.

Opposing Bragg was Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans and the Army of the Cumberland. In late June 1863 Bragg gathered his forces to defend the strategic rail junction of Chattanooga in southeastern Tennessee. Rosecrans, feeling in need of reinforcements, continued a slow campaign of maneuvering. Early in August, he crossed the Tennessee River 30 miles west of Chattanooga. Next, Rosecrans moved well south of Chattanooga toward Lookout Mountain, aiming at the Western & Atlantic Railroad. If that important rail line was cut, Bragg would receive no supplies in Chattanooga from the south. On September 6 Bragg chose to abandon the city and save his army by withdrawing south across the Tennessee-Georgia border.

Alarmed at the deteriorating situation west of the Appalachian Mountains, Confederate President Davis wanted Bragg to make another advance into Tennessee. To augment his resources, Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar, who was in charge of Confederate forces in eastern Tennessee, was placed under his command, as were the divisions of Major Generals John C. Breckinridge and W. H. T. Walker from the Army of Mississippi. Most unusual of all, Longstreet would bring the divisions of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood and Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws by rail from Virginia.

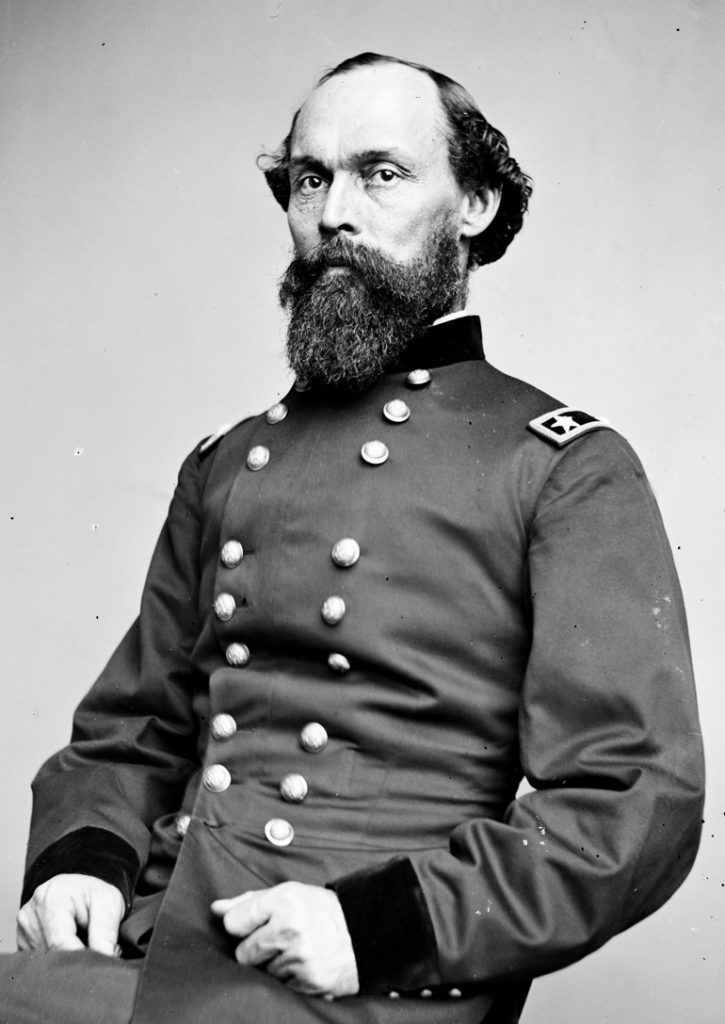

Rosecrans took the risky step of dividing his army as he pushed southward to cut off Bragg’s retreat. The Army of the Cumberland was composed of the XIV Corps under Thomas, the XX Corps under Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook, the XXI Corps under Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, and the Reserve Corps under Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger.

Born in 1816 in Newsoms, Virginia, Thomas graduated from West Point in 1840. Afterwards, he compiled a long record of service in the War with Mexico and antebellum Indian wars. Unlike most of his fellow Southern-born officers, he stayed with the U.S. Army in 1861.

Thomas’ loyalty served the Union well at key battles in 1862, including Shiloh, Perryville, and Stone’s River, and propelled him to the rank of major general and to the command of the XIV Corps. Little did the Virginian know that before long, in the dark and tangled woods on the eastern slopes of Missionary Ridge, he would find himself the de facto commander of the Army of the Cumberland.

After Army of the Cumberland crossed the Tennessee River, Crittenden’s corps was the northernmost, crossing Missionary Ridge south of Chattanooga. McCook’s corps was more than 30 miles south of Crittenden heading through Winston’s Gap, and Thomas’ corps was marching for Steven’s Gap, halfway between the other two corps.

Had Bragg a bit more luck and a functional working relationship with his subordinates, Rosecrans might have been handing his army to the Confederates on a silver platter. The Confederates prepared to strike the isolated Union detachments. But poor coordination and the contempt Bragg’s generals had for him and his orders led to a long series of mistakes and missed opportunities that allowed Rosecrans to reassemble his forces. The Yankees regrouped at West Chickamauga Creek, a dozen miles south of Chattanooga and about four miles south of the Tennessee-Georgia border, on the night of September 17-18.

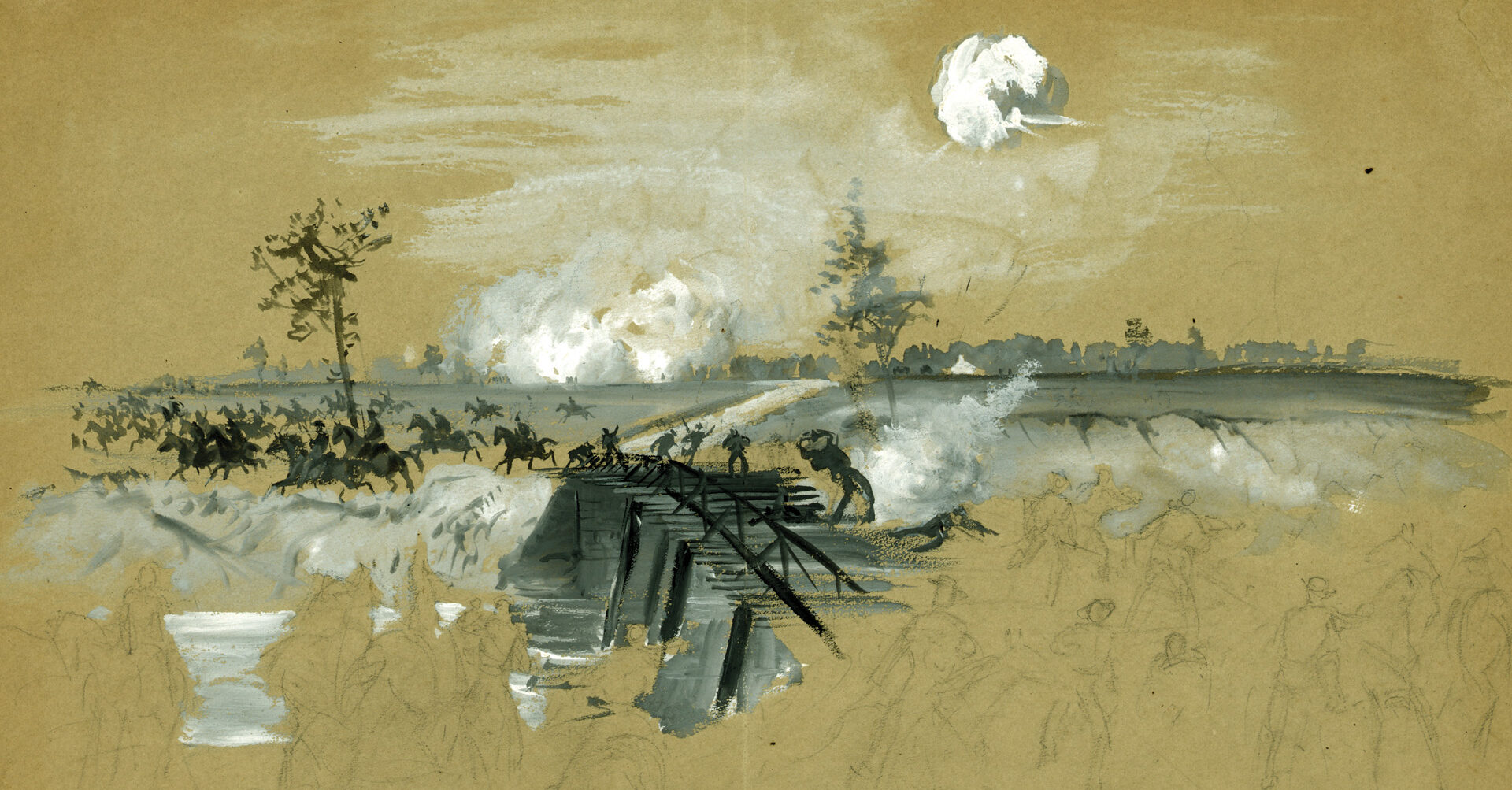

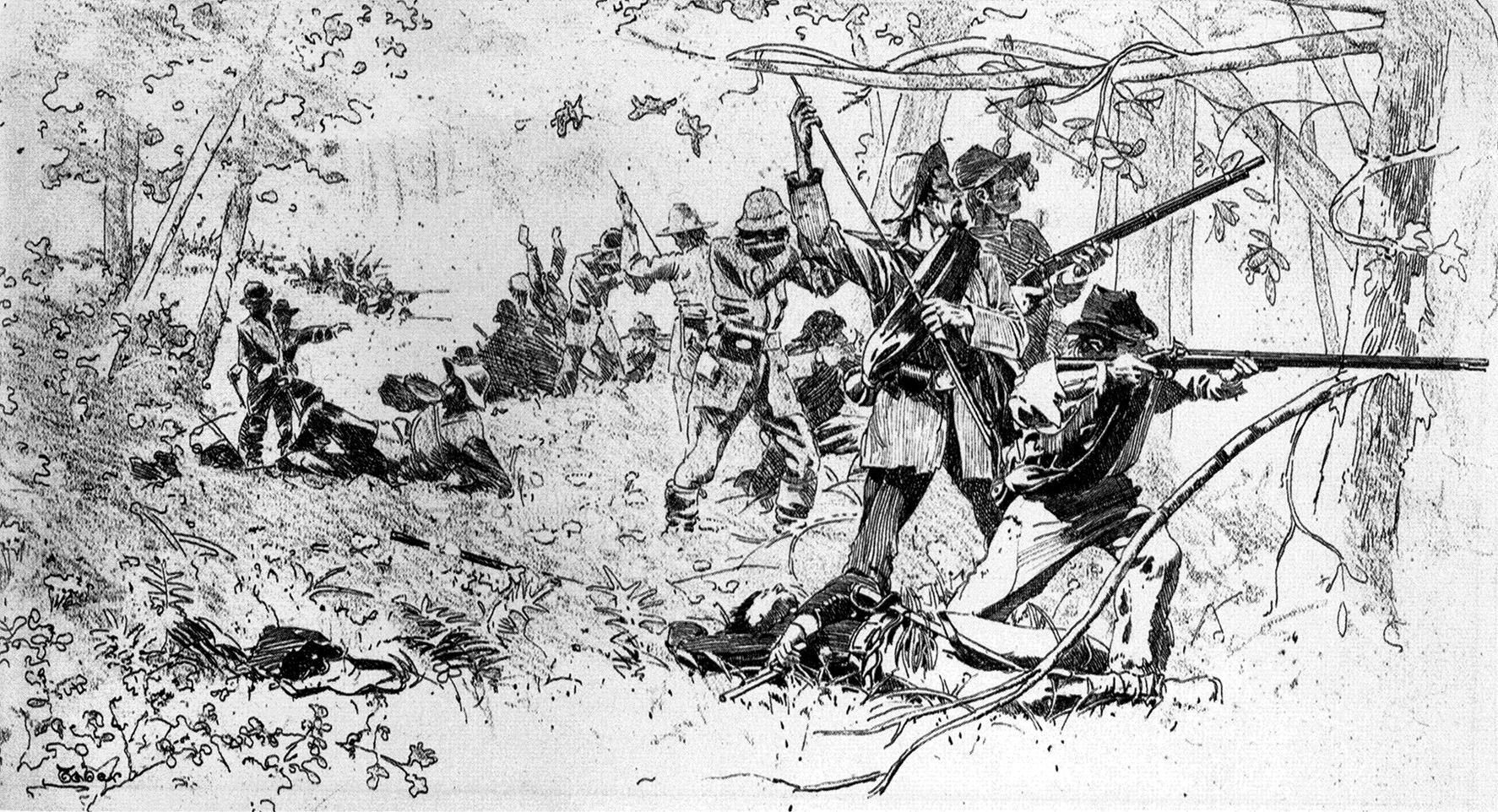

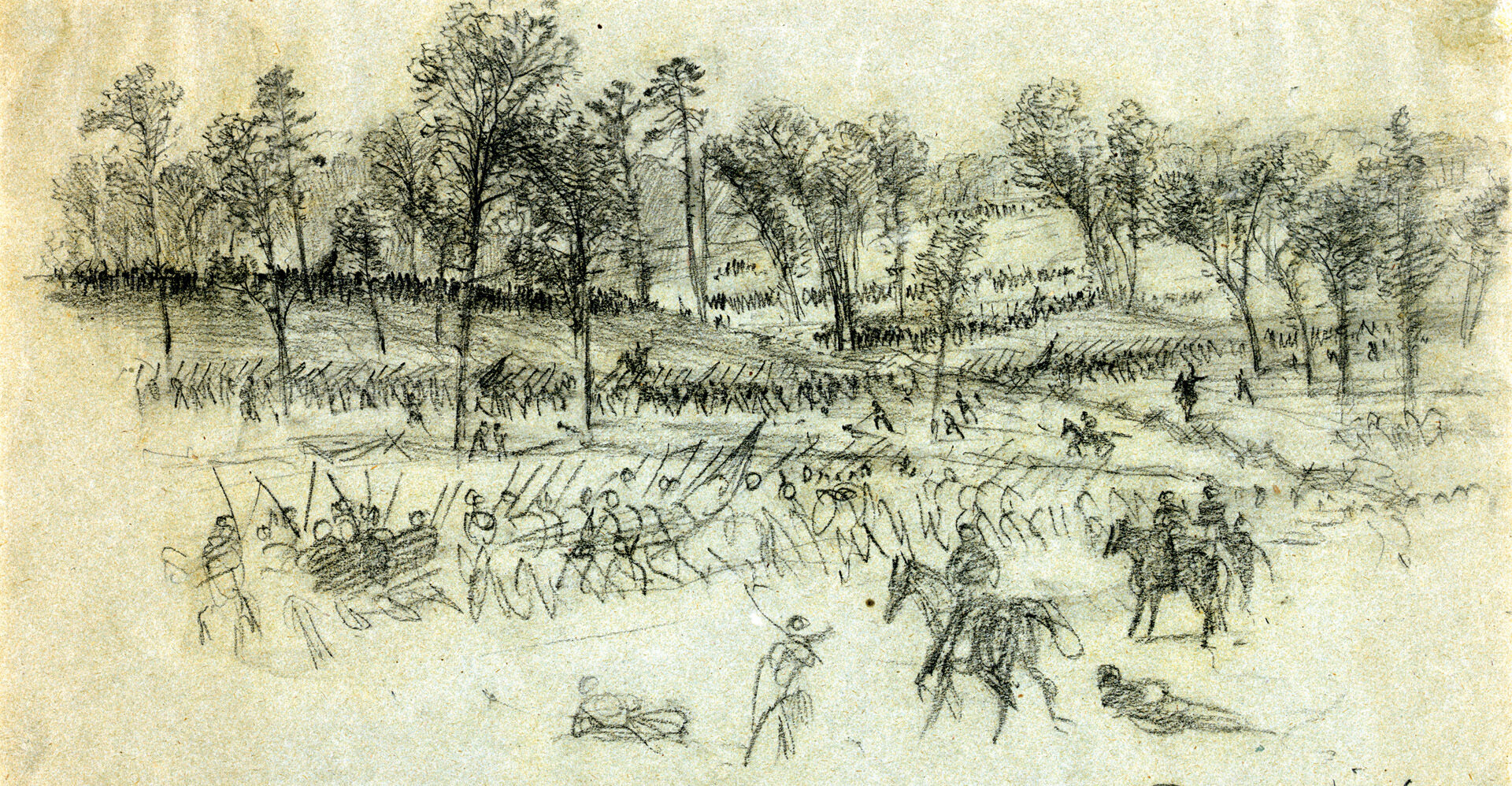

On Friday, September 18, sharp skirmishing by Union cavalry and mounted infantry delayed the Confederate crossing of West Chickamauga Creek for several hours. Companies and regiments clashed in the shady woods surrounding the creek, amid such lavish vegetation that their officers could scarcely see the enemy or even all of their own men.

The land was “undulating and covered with original forest timber, interspersed with undergrowth, in many places so dense that it is difficult to see 50 paces ahead,” wrote Thomas. The brushes with the enemy that day were a prelude to two days of far-more intense fighting that would unfold over the next two days in the dark, densely forested land.

On the evening of September 18, Rosecrans held part of the southern stretches of Missionary Ridge. Roughly 10 miles long, the ridge arose southwest of West Chickamauga Creek and stretched past the Tennessee boundary, running as far as the edge of Chattanooga. The ridge’s name went back to 1817, when the Brainerd Mission was founded to proselytize among the Cherokees, who lived in the region before their forced expulsion to the Indian Territory in the late 1830s. From Missionary Ridge, the eastern slopes rolled downwards toward West Chickamauga Creek, which meandered in a northerly direction toward South Chickamauga Creek, a tributary of the Tennessee River. Chickamauga is said to mean “River of Death” in the Cherokee language, reflecting the grim memory of a smallpox epidemic decades before the war.

Much of the Union line followed the Lafayette Road, which ran south toward the town of Lafayette, 15 miles distant. Amid miles of what seemed like primeval forest, a couple of dozen farms stood on what would become the battleground. Carved from the tree cover, most farms had a cleared field and a handful of sheds or other outbuildings. By the time of the battle, the cornfields had been harvested and cleared, and some fallow fields not yet overgrown also provided some widely scattered clear spaces. Worm fences bound some of the fields; these fences would prove a deadly hindrance to charging Confederate troops and a boon to Union troops, who saw them as furnishing ready-made materials for hastily built field works.

The field owned by the Kelly family, well over half a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide, rested on the eastern side of the Lafayette Road. The Poe family had cleared a large field half a mile south of Kelly’s field, and the cabin and clearing of the Widow Glenn was another mile and a quarter south of Poe’s field.

On Saturday, September 19, Brig. Gen. John Brannan’s division moved toward West Chickamauga Creek, where it was confronted by dismounted soldiers of Forrest’s cavalry. Firing intensified, and nearly all the Union and Confederate units were sent piecemeal into the battle. Floundering almost blindly amid the thorny thickets and heavy brush in the undergrowth of the tree-covered terrain, some regiments and companies suffered deadly losses. Battle lines stretched across as much as six miles of land, but neither Rosecrans nor Bragg had a precise knowledge of their own deployments, much less those of the enemy. Saturday’s chaotic clashes sputtered out with only inconclusive results.

After a tedious and roundabout journey on the Confederacy’s overworked railways, Longstreet’s men had begun arriving at Chickamauga on September 18. Neither Bragg nor his staff extended the courtesy of sending anyone to meet Longstreet when the distinguished general, known in the East as General Robert E. Lee’s “Old War Horse,” got off the train while the battle was underway on September 19. He had received his nickname after the Battle of Antietam, when Lee had greeted his reliable corps commander affectionately by saying, “Ah! Here is Longstreet, my old war horse!” Longstreet’s steadiness in the turmoil of battle, which Lee valued highly, might serve Bragg well on the second day, provided the army commander took full advantage of it.

Gingerly finding their way to the battlefront in the dark, Longstreet and his staff brushed past enemy pickets and arrived safely at Bragg’s headquarters at 11:00 pm Bragg reshuffled his command structure to accommodate the arrival of Longstreet and his troops. He split the army into two wings, giving the right wing to Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk and the left wing to Longstreet.

Many of the reinforcements from the Army of Northern Virginia were still on their way, but five brigades with 9,000 men were on hand for the fighting on September 20. The new arrivals brought the Confederate army up to 68,000 men, enough to outnumber the Yankees by 10,000. Chickamauga was one of the rare instances when the Confederate army outnumbered the Union army.

Rosecrans ordered his men to fortify their positions. In the Confederate lines “the ringing of axes could be heard all night in our front,” wrote Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, who commanded a corps in Polk’s right wing.

“It was a cold night and the ground was white with frost,” recalled a soldier of the 75th Indiana. “No fires were permitted to make coffee,” wrote another soldier in the 35th Ohio, who added, “Fires would point out to the enemy the position of our lines.”

Despite their discomfort, the bluecoats could regard the previous day as reasonably successful. Over the last several days Bragg had been unable to pounce on and crush any of the isolated detachments of the Union Army, which would have been too far apart for mutual aid. Now, their forces were united, and they held off the Rebel army in the first day’s fighting. West of the Appalachians, Union soldiers could look back on more successes and victories than failures, and it was understandable if they felt like victory would be theirs on the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga.

At the Widow Glenn’s house, the Union brass held a long late-night war conference. Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, who was then with the Army of the Cumberland, noted that the XIV Corps commander, whom his soldiers affectionately called “Pap Thomas,” dozed off several times during the meeting. Thomas and his fellow generals had gotten little sleep in the last couple of days. Dana noted that Thomas’ contribution to the discussions was only to say, “I would strengthen the left,” before the tired general dozed off again. Whether or not this was true, it neatly summed up the importance of Thomas’ role in the next day’s battle.

Soldiers of Thomas’ wing of the army awoke well before dawn. They shuffled across the frosty ground into the battle line before eating a breakfast of hardtack and raw bacon. Details sent to find water had no luck in refilling their empty canteens. Bragg’s men held West Chickamauga Creek, which still ran deep with ice-cold water. After a spell of hot and dry summer weather, though, the brooks, branches, and springs in Union hands offered little more than muddy trickles.

The Union line was shaped like a question mark. At the top of the question mark, the line held by four divisions (those of Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird, Brig. Gen. Richard Johnson, Maj. Gen. John Palmer, and Maj. Gen. Joseph Reynolds) formed a salient pointing east from the Kelly House.

Brig. Gen. John Turchin’s Brigade of Reynolds’ division was the rightmost element of the arc forming the salient. From there, the remainder of Reynolds’ division stretched southward along the Lafayette Road. Connecting with them, the left of Brannan’s Division touched the Lafayette Road, while its right was 200 yards west of the road. Next, Maj. Gen. James Negley’s division was arrayed past the Dyer Road, overlooking the cleared lands of the Brotherton Farm. Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s division and Colonel John Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade, whose troops were armed with Spencer repeating rifles, were near Rosecrans’ headquarters at the Widow Glenn’s house. In reserve, the divisions of Brigadier Generals Horatio Van Cleve, Jefferson C. Davis, and Thomas Wood waited north of the headquarters and in the rear of the right-flank divisions.

Bragg planned to send his rightmost units to attack first, beginning with Breckinridge’s division. Each division in Polk’s wing then would move in succession at intervals, giving Longstreet some final minutes to complete his dispositions before throwing his troops against the Union right. Here again, Bragg’s dysfunctional command structure undid the potential for a sharp start to the second day’s fighting: Polk never relayed Bragg’s orders to his subordinate Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, who was in charge of the divisions of Major Generals John Breckinridge and Patrick R. Cleburne. Hill, for his part, did nothing to seek instructions, and Breckinridge therefore stayed put as Bragg waited for something to happen.

Anticipating that the heaviest attacks would be aimed at him, Thomas pleaded for reinforcements. Rosecrans thought that Negley’s division was in reserve and sent him to join Thomas; however, it turned out that Negley was in line of battle and not in reserve. Wood’s division, which was in reserve, was ordered forward to take Negley’s place. It seems that Wood did not move quickly enough to suit Rosecrans, and he drew a sharp rebuke from his superior.

In lower ground than the Union positions, and closer to the waters of West Chickamauga Creek, the Confederates waited in the chilly, misty morning. Longstreet listened intently for the sound of gunfire, which would signal him to send his men forward. But as the sun rose higher and time slipped past, he heard nothing and so stayed in place.

In the Union lines, Lt. Col. Henry V. Boynton of the 35th Ohio waited in what he saw as “the painful quiet of that Sabbath morning” as the two armies drifted closer together until “there was scarcely any point the length of a tiger’s spring between them.”

Realizing from the continued quiet that something was wrong, Bragg sent fresh orders for all of his generals to attack at once. “At 9 o’clock that Sabbath service of all the gods of war began,” wrote Boynton. “It broke full-toned with its infernal music over the Union left, and that morning service continued there till noon.”

Polk’s attacks were delivered bit by bit, usually no more than a brigade at a time. Breckinridge charged Thomas’ works at midmorning. The Union fortifications around the Kelly Farm, rushed to completion during the previous night, were described in great detail by William F. G. Shanks, a war correspondent for the New York Herald. “General Thomas had wisely taken the precaution to make rude works about breast-high along his whole front, using rails and logs for the purpose,” wrote Shanks. “The logs and rails ran at right angles to each other, the logs keeping parallel to the proposed line of battle and lying upon the rails until the proper height was reached. The spaces between these logs were filled with rails, which served to add to their security and strength. The spade had not been used.”

Without a doubt, piling up stones, stumps, and logs was far easier for Union soldiers worn out by long marches than digging around the forest trees and through their networks of tangled roots.

In front of the Union line, forested land offered little visibility and no room for effective maneuvering of battle formations. Charging Confederates might see little more of the enemy than the powder smoke floating amid the tree cover.

“[The] breastworks, behind which we felt so secure, consisted of three pine logs, two on the ground, close together, while the third one was placed on top of these, and made a defense of two and a half or three feet high, according to the size of the logs,” wrote regimental historian Charles C. Bryant, then a lieutenant in the 6th Indiana. “By getting down behind these logs, only our heads, or perhaps our heads and shoulders, would be exposed, and then I want to tell you that these logs are mighty good things to stop bullets.”

Breckinridge tried to move around the Union left flank to reach the rear. Some of his men crossed the Lafayette Road, but were unable to break through to the interior of Thomas’ salient.

Next, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s division struck the Union line. As the Confederates pressed forward, their alignment was disrupted by the tangled brush. Their advance also was disrupted by heavy fire from enemy troops who were nearly hidden from them. Cleburne’s men reeled back 400 yards to a wooded ridge. Brig. Gen. James Deshler, who commanded a brigade in Cleburne’s division, surveyed the ammunition supply in preparation for the next attempt to storm the enemy works, but was struck dead by a Yankee shell. The Confederates on the ridge did not charge again, and the two sides settled into a brisk exchange of fire.

Earlier that morning, the 6th Ohio of Palmer’s division spent an hour and a half building some breastworks as Rebel snipers and cannon occasionally fired into them. After their labor, they were pulled back to form a reserve behind and to the left of two of their division’s brigades that were in the front line.

In Thomas’ tightly pressed salient, being in reserve offered little safety. In a letter written after the battle, an unidentified officer of the 6th Ohio saw four columns of Confederates, who were probably some of Breckinridge’s men, assembling 200 yards in their front, “with two generals riding along the lines encouraging their men,” the officer said. The officer said that he sent “two men—splendid shots, both of them—to go forward, and, if possible, pick off the officers that I had seen riding up and down the rebel lines.”

Colonel William Grose, who commanded a brigade in Palmer’s division, sent two guns of the 4th U.S. Artillery to aid the Ohioans. “The Confederates opening a battery on us simultaneously, the firing became brisk,” wrote Grose. “Another battery to the rear of our line got excited, and began playing upon us with canister, apparently mistaking us for the enemy. We were thus under a heavy fire from both the front and rear, and naturally hugged Mother Earth very closely…. The battery continued to play on us, notwithstanding our color-bearers bravely rose up and waved our flags to show the artillerists who we were.”

Before a courier ordered the Yankee gunners to shift their fire, “a number of men and officers were hit,” continued Grose. “Our regiment was much demoralized by this; they said they could stand the rebel fire, but when it came to being shot by our own men, they were played out.”

The morning’s attacks gained the Confederates nothing and shattered one brigade after another. By midday, Polk’s futile assaults had slowed; the horrendous toll of casualties had not dented the Union lines around Kelly’s Farm.

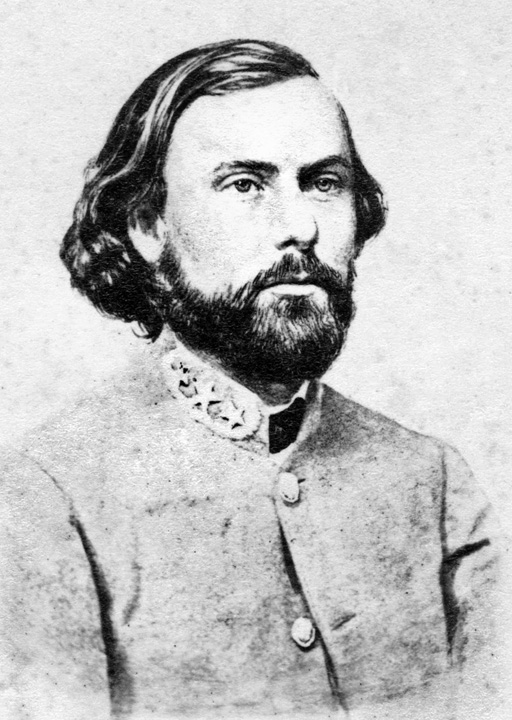

Hindman

As Polk wore down his troops in the desperate charges, Union staff officer Captain Sanford C. Kellogg rode to Rosecrans’ headquarters and reported that Reynolds’ flank was left in the air by a large gap in the lines. Under the mistaken impression that General Wood was placed nearby on Reynolds’ right, Rosecrans ordered Wood to shift to his left, instructing him to “close up and support Reynolds.”

But it was not Wood who occupied the ground to the right of Reynolds. In truth, Reynolds’ flank was amply protected by Brannan’s division, and there was no significant gap between them. The abundant foliage completely hid Brannan from Kellogg’s gaze. Wood actually was well away from Reynolds on Brannan’s right, and moving his division as ordered would open a space between Brannan and the divisions of Davis and Sheridan. But Wood took no chances of a further reprimand. He started his men moving, and they slipped behind Brannan to regroup with Reynolds.

As fighting along Polk’s front ebbed, Longstreet sent his men toward the Federal lines. The divisions of Maj. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson, and Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman formed the front line, arranged from north to south beyond the Lafayette Road. Intense fire coming from Brannan’s division, hidden by the trees and their field works near the Poe House, stalled Stewart’s advance.

Johnson’s troops, in the center, pressed toward the Brotherton Farm and its cleared field, just beyond the Lafayette Road. They took heavy fire on both flanks. But, no bullets came at them from their front, as they faced the stretch just vacated by General Wood.

With no enemy troops in their front, part of Johnson’s division pushed straight through the woods behind the Brotherton Farm and burst into the clearings of the Dyer Farm. Another section swung to the right to strike Wood’s withdrawn regiments and Brannan’s flank and rear. Brannan’s line collapsed. Behind them, Van Cleve’s men were surprised and quickly broke as well.

Davis and Sheridan moved to fill the widening gap, but Hindman’s troops surprised and scattered them. On the tip of the Union right, Wilder’s mounted brigade held on and drove back a charge of Manigault’s brigade. Near the Widow Glenn’s house, Brig. Gen. William H. Lytle, who commanded a Union brigade in Sheridan’s division, lost his life in a valiant but doomed stand that slowed Bushrod Johnson’s troops, at the cost of much of his brigade. Elsewhere, Rosecrans’ right was shattered and driven back from their positions.

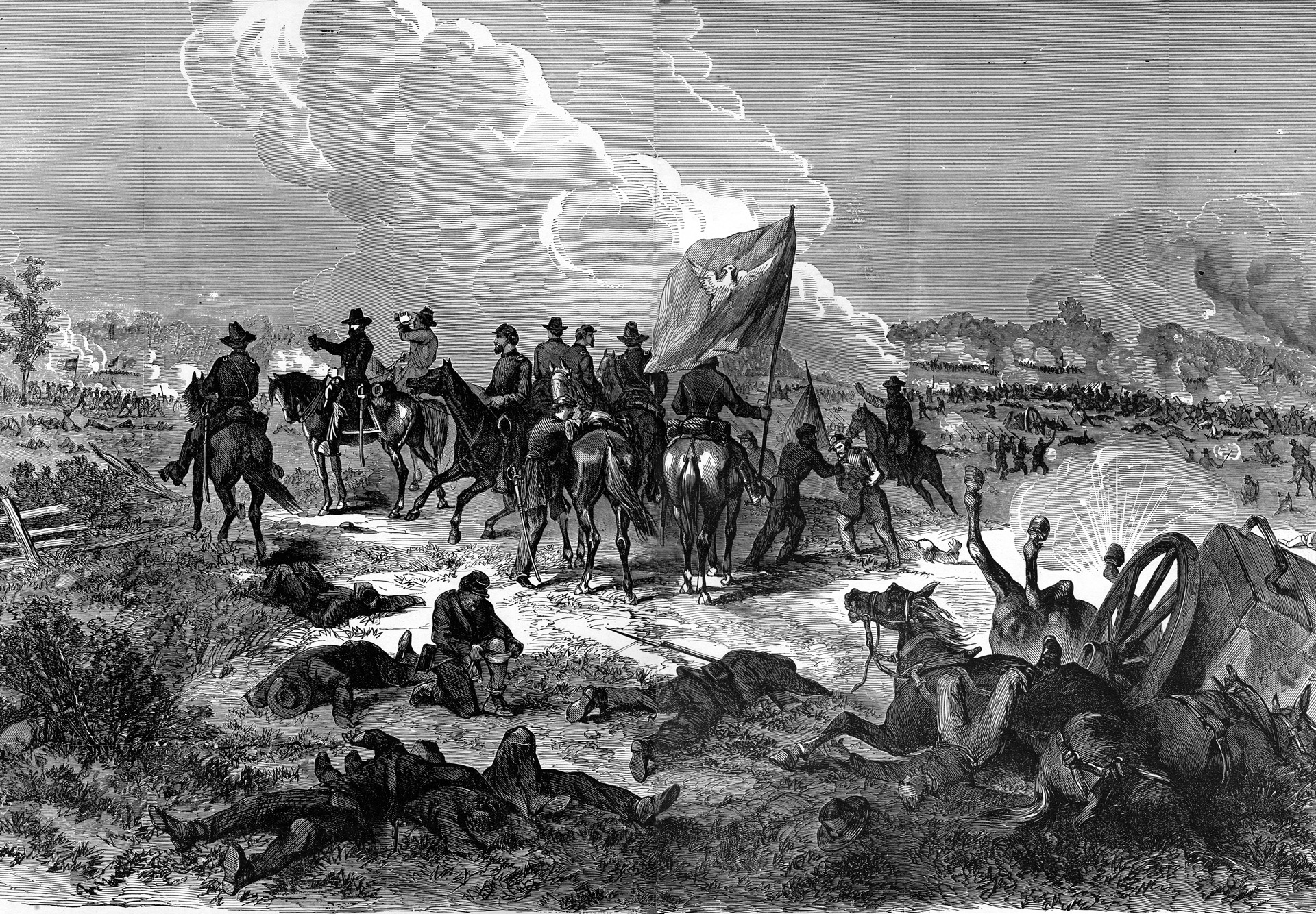

Dana, who was an experienced journalist, left colorful accounts that shaped perceptions of Chickamauga on the day of the battle and in postwar histories. He left a dramatic glimpse of Rosecrans when it seemed the Army of the Cumberland was dissolving into chaos.

“The first thing I saw was General Rosecrans crossing himself—he was a very devout Catholic,” recalled Dana, who added, “If the general is crossing himself, we are in a desperate situation.” Dana said that Rosecrans warned him, “If you care to live any longer… get away from here.” Just then, Dana witnessed the flight of the shattered right-flank soldiers, flying away, in his words, “[like] leaves before the wind.” When he reached Chattanooga some hours later after a frantic ride, Dana sent an alarming telegram to Washington, warning of the unfolding disaster.

Rosecrans and his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield, were swept along with the mobs of fleeing soldiers pushing toward McFarland’s Gap. They could hear little of the battle, and Rosecrans and his aide even placed their ears to the ground in an attempt to hear the vibrations of the battle. In the confusion, they had received no news of Thomas.

Garfield talked Rosecrans out of risking a ride to Thomas to direct the remnants of the army. The chief of staff believed it was far better that Rosecrans avoid capture and focus his efforts on organizing a last-ditch defense of Chattanooga with the surviving fragments of the Army of the Cumberland.

But the situation was not nearly as grim as it looked to the soldiers in the broken regiments cascading toward McFarland’s Gap. Wilder’s brigade was detached from the main army, but they were on the prowl to disrupt Confederate movements. A few miles to the rear, Granger’s reserves were available. Brannan’s division had swung back to join Thomas, who also collected soldiers from the broken divisions of Wood, Negley, and Van Cleve.

Thomas arrayed the new arrivals at a right angle to his old line. They held a spur of Missionary Ridge known as Snodgrass Hill after the farming family who owned the land. Perched on that high ground, the soldiers protected Rosecrans’ retreat and kept the Confederates from turning Thomas’ right. If Longstreet’s men broke, though, they could destroy the only force capable of preventing a determined Confederate advance to the banks of the Ohio.

Initially, Snodgrass Hill had been unoccupied, as it was well out of the way of Polk’s troops. There were pros and cons to defending it. On the one hand, there were no existing defenses on it, so the soldiers had to pile up barricades in between Longstreet’s onslaughts. On the other hand, its natural formation afforded good protection. Snodgrass Hill was “admirable for defense, the ridge proper, and the spurs, sloping off toward the enemy in all directions, forty-five degrees, and covered with oak and other trees. Up these heights the enemy must charge,” wrote Lt. William Wirt Calkins of the 104th Illinois.

Among the Union defenders were Colonel Charles G. Harker and his brigade of Wood’s division. Thomas rode through his command to encourage the men. “This hill must be held and I trust you to do it,” he warned Harker. “We will hold it or die here,” Harker replied. Shortly thereafter Thomas met with one of Harker’s regimental commanders, Colonel Emerson Opdycke of the 125th Ohio. “This point must be held,” Thomas said. Opdycke told him, “We will hold this ground, or go to heaven from it.”

When Lt. Col. Judson W. Bishop reported to Thomas with the 2nd Minnesota, the general told Bishop that he “was glad to see us in such good order.” Bishop’s regiment shored up the right flank just as the Confederates massed for another assault.

With Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw, an experienced commander from the Army of Northern Virginia, taking over the division of the wounded Hood, Johnson and Hindman joined them for another surge. Polk’s wing was exhausted by the costly and futile attacks of the morning. Bragg would not commit them to aid Longstreet, so they played only a minor role in the afternoon’s fighting.

“Ranks followed ranks in close order, moving briskly and bravely towards us,” wrote Bishop. “It was theirs to advance, ours, now, to stand and repel. Again the order was passed to aim carefully and make every shot count, and the deadly work began. The front ranks melted away under the rapid fire of our men, but those following bowed their heads to the storm of bullets and pressed on, some of them falling at every step, until, the supporting touch of elbows being lost, the survivors hesitate, halt, then turning, start back with a rush that carries everything with them to the rear.”

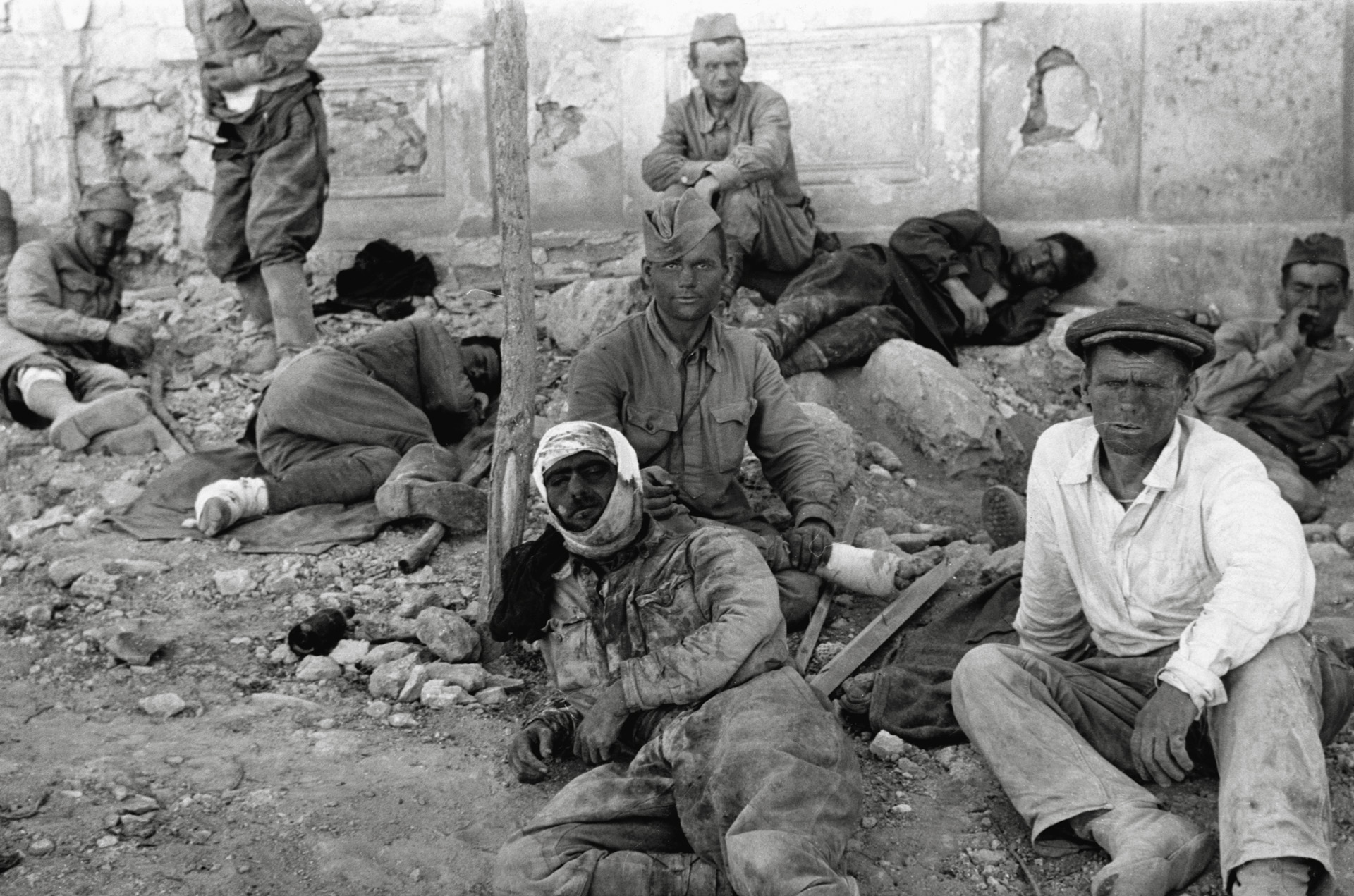

The storm of bullets was “as deadly in the wild retreat as in the desperate and orderly advance,” continued Bishop. “This was all repeated again and again, until the slope was so covered with dead and wounded men that looking from our position we could hardly see the ground.”

Shanks noticed that the mounting stress affected the usually unflappable Thomas. The strain “cast a visible cloud over the general’s spirits, and excited his nerves to an unusual degree,” wrote Shanks. Early in the afternoon, Thomas and his staff officers could see from their saddles a growing cloud of dust arising in the distance several miles to the north. “If it dissolved to reveal friends, then they were doubly welcome,” Shanks wrote. But for all they knew, it might be more Confederate infantry. Even worse, it might be Forrest’s dreaded cavalry.

According to Shanks, General Wood offered some reassurance. “Don’t you see the dust rising above them ascends in thick misty clouds, not in spiral columns, as it would if the force was cavalry,” Wood said to Thomas. “Take my glass, some of you whose horse stands steady [and] tell me what you can see,” said Thomas. Peering through his field glass, Shanks said that he was positive that he could see the United States flag.

Thomas dispatched Captain Gilbert Johnson, a staff officer, to identify the approaching troops. Johnson had a dangerous ride, dodging shots from Rebel sharpshooters, until he neared the approaching column and saw the Stars and Stripes waving over the heads of the troops.

Tension mounted on the hill, as Captain Johnson was gone for some time. Suddenly he reappeared, riding out of the willow trees that lined a small stream some distance to the rear. The staff heard rifle shots, and Shanks wrote that they saw Johnson spur his horse and “disappear in a thick wood in the direction of the coming mass of troops still enveloped in clouds of dust. In a few minutes he again emerged from this timber, and following him came the red, white, and blue crescent-shaped battle-flag of Gordon Granger.”

Granger had arrived with the two brigades of Brig. Gen. James B. Steedman’s First Division of the Reserve Corps. The 4,000 men also brought 100,000 spare rounds of ammunition. After Steedman and Granger shook hands with Thomas, the commander was again his stoic self. The new arrivals were sent to the right of Bishop’s embattled 2nd Minnesota, along a rocky elevation west of Snodgrass Hill that was later known as Horseshoe Ridge, even though it was not shaped like a horseshoe.

At 2:30 pm Longstreet and his staff paused for a brief lunch of sweet potatoes, which seemed a small luxury as they were scarce in Virginia. A courier arrived, with orders for Longstreet to report to Bragg. Longstreet was enthusiastic about their progress. He believed 60 guns were taken, and spoke of capturing masses of prisoners and supplies. But Bragg saw the battle very differently. Nothing at all had impressed him other than the staggering losses endured when so many of Polk’s men were slaughtered in vain that morning. According to Longstreet, Bragg refused to provide reinforcements stating that “there was no more fight in the troops of Polk’s wing.”

Longstreet was puzzled by Bragg’s decision to pull his headquarters back some distance to Reed’s Bridge on West Chickamauga Creek. It gave the impression that “Bragg thought at 3:00 pm that the battle was lost,” Longstreet wrote afterwards to Daniel Harvey Hill, who had served alongside him at Antietam.

Colonel William H. Stoughton commanded a Union brigade during the attacks on Snodgrass Hill. “Our ammunition became exhausted during the fight and every cartridge that could be found on the persons of the killed and wounded as well as in the boxes of the prisoners were taken and distributed to the men,” Stoughton recalled.

The ammunition scrounged from the casualties and prisoners could carry the regiment only so far. Lieutenant William D. Whitney of the 11th Michigan knew by 5:00 pm that they were running out of cartridges. “The enemy [was] about 100 yards in our front, preparing for another charge, and their sharpshooters were firing at every man who showed his head above our light works,” wrote Whitney. “The dead and wounded lay in great numbers, right up to our works.”

“They were armed with Enfield rifles of the same calibre as our Springfield rifles,” continued Whitney. “I don’t know what prompted me, but I took my knife from my pocket, stepped over the works, and, while my company cheered and the Confederates made a target of me, I hurriedly passed along the front, cutting off the cartridge boxes of the dead and wounded, and threw them over to my company. Thus I secured a few rounds for each of my men. The enemy made one more charge and was again repulsed.” Lieutenant Whitney became one of nine soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor for their conduct at Chickamauga.