By Sheldon Winkler

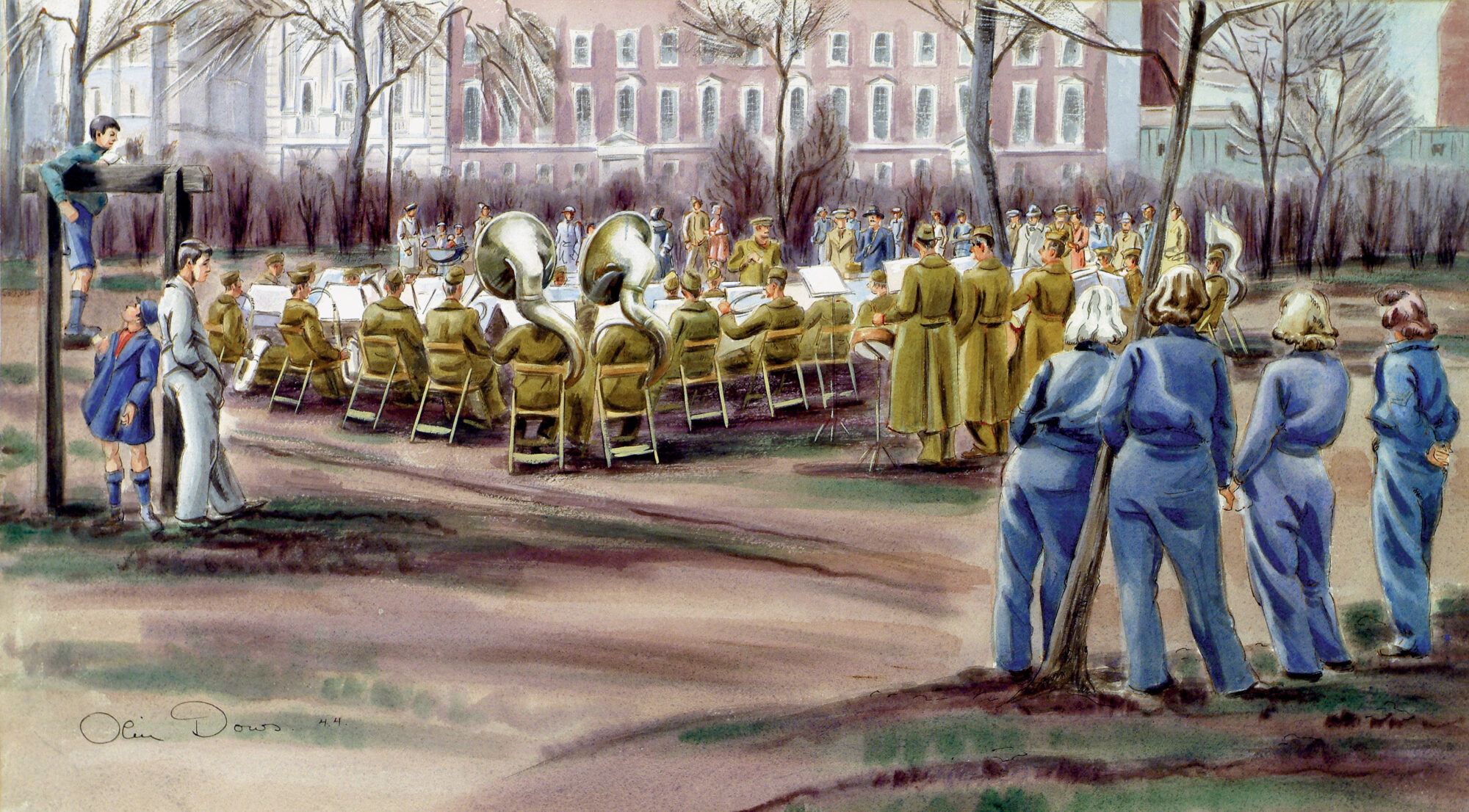

Some of the most memorable and enduring popular music of the 20th century was written during World War II. Patriotism was at an all-time high, which was reflected in entertainment and popular culture. The war effort became an integral part of the entertainment industry, which responded to the collective wishes and desires of the people. An emotional wartime dream world of heroes, love, remembrance, reflection, and introspection emerged that has become more appealing as time passes.

The popular music of the early 1940s reached a high level of excellence and is considered by many to be America’s finest. While the percentage of war-oriented songs directly inspired by World War II was small compared to the total output of popular songs composed during that period, a large number of these musical compositions have survived to become standards that remain popular to this day.

War songs were sentimental, poignant, patriotic, morale-building, and somber. Some were written in response to political and social situations created by the war. There is no doubt that popular music was successful in bolstering the morale of the troops as well as those on the home front, easing fears and longing, providing hope, and serving to unite all Americans as a nation during those turbulent years.

When the United States entered the war in December 1941, the country was not without a number of patriotic war songs. “God Bless America,” originally written by Irving Berlin for a World War I wartime review (withheld at the time and later revised), was sung publicly for the first time during a CBS radio broadcast on Armistice Day, November 11, 1938. It was sung live by Kate Smith and recorded by her in March 1939. It is probably more favored today than at any time in the past and has been suggested as a replacement for the national anthem because of its patriotism, simple melody, and immense popularity.

One of the most beautiful war songs that is still popular today, “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square,” was recorded in the United States by Glenn Miller, with a vocal by Ray Eberle, on October 11, 1940, after first gaining popularity in England. The composition served as background music for a wartime suspense motion picture, Man Hunt, starring Walter Pidgeon, and was also the title of a popular postwar movie.

Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern’s “The Last Time I Saw Paris” lamented the German occupation. “My Sister and I,” based on the diary of a young Dutch boy who emigrated to the United States with his sister, was a musical tribute to the refugee children of Europe. It was recorded by Jimmy Dorsey, with a vocal by Bob Eberly, and the Dick Jurgens Orchestra. The diary itself, published in the United States in book form, became a best-seller.

Antiwar sentiment was expressed in William Malone’s “Stop That War,” with the often repeated line “them cats are killing themselves.”

“We’ll Meet Again,” probably Vera Lynn’s most popular song, was written in 1939 and sung by her in a 1942 movie of the same name. She originally sang the song while touring with the Ambrose Orchestra in 1939, and it later became the signoff song for her BBC radio program, Sincerely Yours, to the troops. Ms. Lynn thought the song was ideal to end her radio broadcasts because it was “optimistic.” “We’ll Meet Again” later became the theme song of a popular 1940s U.S. radio program, Mr. Keene, Tracer of Lost Persons, and in 1964 was used as background music for the movie Dr. Strangelove.

Vera Lynn’s songs brought the English hope, comfort, and inspiration during the darkest days of World War II. British servicemen adored her so much that she was voted “The Forces’ Sweetheart.” She was often referred to as England’s most beloved export to the United States.

Other popular songs that preceded America’s entry into World War II included Irving Berlin’s “Any Bonds Today” and “Arms for the Love of America” recorded in June of 1941. Harry James recorded and Helen Forrest sang “He’s 1-A in the Army and He’s A-1 in My Heart” in October of 1941. Kay Kyser recorded “(There’ll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover” in late 1941. Although other artists recorded this song, including Kate Smith, Glenn Miller, Sammy Kaye, and Jimmy Dorsey, Kyser’s version, with a vocal by Harry Babbit, was the most popular in the United States. The song originally achieved success in England, with the help of a Vera Lynn recording with the Mantovani Orchestra. The song has been most associated with Vera Lynn since its introduction.

A plethora of songs were written as a result of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Glenn Miller completed a scheduled recording session the day after the attack and changed the title of one of the songs he recorded from “That’s Where I Came In” to a more war-like “Keep ‘Em Flying.”

The first recording of a war-related song, “Goodbye Mama (I’m Off to Yokohama),” was completed a little over a week after Pearl Harbor by Teddy Powell and his Orchestra. Don Reid and bandleader Sammy Kaye wrote “Remember Pearl Harbor,” a composition Kaye’s orchestra recorded on December 17, 1941.

The most successful and most popular patriotic show of World War II, and one of the most unique productions in the history of entertainment, was Irving Berlin’s This Is the Army, which originally began as a Broadway musical. General George C. Marshall gave Berlin permission to stage a revue early in 1942 to raise money for the military. The musical, which was directed by Ezra Stone (radio’s Henry Aldrich), opened on Broadway with a cast of 300 soldiers on July 4, 1942, to rave reviews. The most popular songs from the revue were “This Is the Army Mr. Jones” and “I Left My Heart at the Stage Door Canteen.”

This Is the Army was also significant in that African-American performers were included in the cast at Mr. Berlin’s insistence. This Is the Army thus became the only integrated unit in the military at that time. Among the numbers performed by African-American actors was “That’s What the Well-Dressed Man in Harlem Will Wear.”

This Is the Army was later made into a movie by Warner Brothers, starring future President Ronald Reagan (then a lieutenant), George Murphy, and Joan Leslie. Irving Berlin appeared in the movie and sang “Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” recreating the role he previously played in his World War I musical Yip! Yip! Yaphank! Joe Lewis, Frances Langford, and Ezra Stone also appeared in the movie version, along with Kate Smith, who naturally sang “God Bless America.”

This Is the Army eventually raised $10 million for the Army Emergency Relief Fund.

War songs have been divided by historians, musicians, and authors into a number of categories. While it can be difficult to classify war songs, as a majority of them fall into two or more categories, or no specific category exists, for convenience, this author has separated the songs of World War II into six groupings: patriotic; love, separation, and homecoming; tributes; military service; faith, hope, and devotion; and novelty.

Patriotic songs include “American Patrol,” “That Soldier of Mine,” “There’s a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere,” “Remember Pearl Harbor,” and “This Is Worth Fighting For.”

“American Patrol,” one of the most popular of the patriotic songs, sold over one million copies, with Glenn Miller’s swing approach to a military march being the best seller.

“This Is Worth Fighting For,” a song of introspection, lasted beyond the war years with its stirring words, “I saw a peaceful old valley, with a carpet of corn on the floor … didn’t my folks before me, fight for this country before I was born.” The most noted versions were recorded by Vaughn Monroe and the Ink Spots.

Elton Britt was the first country singer to be awarded a gold record and to perform at the White House. He sang “There’s a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” (for which he received the gold record) for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942. The lyrics told the story of a disabled boy wanting to fight and die for his country.

A number of patriotic songs provided wartime advice for Americans, including “Dig Down Deep,” “Get Some Cash for Your Trash,” “Obey Your Air Raid Warden,” and “Shhh, It’s a Military Secret.”

The largest number of World War II songs can be placed in the category of love songs, many of which are still popular today. Most were tender, written among the fury of heavy fighting. Many of the lyrics made reference to separation anxiety, which was prevalent as a result of the great distances between people. The songs include “A Boy in Khaki, a Girl in Lace,” “As Time Goes By,” “Dear Mom,” “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else But Me),” “Goodbye Mama (I’m Off to Yokohama),” “I’ll Be Seeing You,” “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You,” “I’ll Walk Alone,” “It’s Been a Long Long Time,” “Johnny Doughboy Found a Rose in Ireland,” “My Dreams Are Getting Better All the Time,” “My Guys Come Back,” “Put Another Chair at the Table,” and “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To.”

One of the most memorable songs of World War II was “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else But Me).” Extremely popular up-tempo recordings of this composition were made by Glenn Miller (on February 18, 1942, featuring Marian Hutton, Tex Beneke, and the Modernaires), and the Andrews Sisters.

Although the media had an understanding that American soldiers in World War II would not be called doughboys, the song “Johnny Doughboy Found a Rose in Ireland” was an exception and became a hit anyway. Guy Lombardo’s version, with a vocal by Kenny Gardner, was extremely popular.

“I’ll Be Seeing You,” a 1938 song introduced in an unsuccessful Broadway show titled Right This Way did not make the hit parade until Bing Crosby’s version reached the top spot in 1944. The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, with a vocal by Frank Sinatra, and the Ink Spots also had popular recordings of this song. “I’ll Be Seeing You” was later selected by Liberace as his theme song and achieved additional success after the war.

“Put Another Chair at the Table” was recorded on December 15, 1944, by the Mills Brothers, when lead singer Harry Mills was home on leave from the Army.

“My Guys Come Back” was recorded by Benny Goodman, with a vocal by Liza Morrow, on September 12, 1945. The war had officially ended a week and a half earlier, on September 2, 1945, when the Japanese signed the formal unconditional surrender documents aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. The song’s happy lyrics stated, “No more blues for me … just good news for me.”

Songs of tribute included “Angels of Mercy,” written for the American Red Cross by Irving Berlin, “On the Old Assembly Line” and “Rosie the Riveter” for the American defense worker, and “People Like You and Me” in appreciation of our fighting men.

Not many songs were written about Americans who would not be coming home. A notable exception was “(The Ballad of) Rodger Young,” beautifully recorded by Burl Ives in March 1945. The lyrics tell of Private Rodger Young, who “fought and died for the men he marched among,” and now lies “beneath the silent coral of the Solomons … to the everlasting glory of the infantry.”

Novelty songs attempted to relieve stress and tension. They were happy songs written against a background of dire events. Among the novelty songs, one stands far out in front as the war’s most memorable; Spike Jones’ version of “Der Fuehrer’s Face.” This version, with a vocal by Carl Grayson, sold over one million records.

Other popular novelty or humorous songs were “Rum and Coca Cola,” “There’ll Be a Hot Time In the Town of Berlin,” and “We’re Gonna Have To Slap the Dirty Little Jap.” Some novelty songs had unusual titles, among them, “Harvey the Victory Garden Man,” “I Paid My Income Tax Today,” “He Loved Me Till the All Clear Came,” “Let’s Put An Ax to the Axis,” “There Are No Wings on a Foxhole,” “Wait Till the Girls Get in the Army Boys,” and “Yankee Doodle Ain’t Doodlin’ Now.” An excellent recording of “Yankee Doodle Ain’t Doodlin’ Now” was made by the Dick Jurgens Orchestra with a vocal by Buddy Moreno on January 26, 1942.

Songs of military service included “Bell Bottom Trousers,” “Dreaming of You,” “First Class Private Mary Brown,” “From Taps Till Reveille,” “G.I. Jive,” “He Wears a Pair of Silver Wings,” and “This Is the Army Mr. Jones.”

“This Is the Army Mr. Jones” presented a point of view of the army from inside looking out. “G.I. Jive” told about the humorous side of Army life (“meals in a beautiful café they call the mess”) and mixed jive talk with Army jargon. “Dreaming of You” spoke about the sad side of Army life. “Bell Bottom Trousers” became very popular late in the war. It was recorded by a number of artists, including Jerry Colonna, Kay Kyser, Guy Lombardo, and Tony Pastor.

Wartime songs of faith and devotion included “Be Brave Beloved,” “Comin’ in on a Wing and a Prayer,” “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” and “When the Lights Go on Again (All Over the World).” These compositions offered a bit of optimism among a series of discouraging events. The lyrics of “Be Brave Beloved” contained phrases like “our love will see us through,” and “we’ll be together again.”

The phrase “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” was credited to Navy Chaplain Howell Forgy, who uttered these words as ammunition was being passed to load the guns of the heavy cruiser USS New Orleans while Pearl Harbor was under attack. Being a chaplain, Forgy could not man a gun or handle shells and powder, but he could offer words of encouragement, which inspired one of the war’s most popular songs. “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” was first recorded by the Merry Macs on July 29, 1942, but it was Kay Kyser who later had the best-selling version. “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” was one of a number of World War II songs that linked battle scenes with a religious message.

“Comin’ in on a Wing and a Prayer” was another of the war songs that combined battle events with inspiration. It was beautifully recorded by the Four Vagabonds, a quartet noted for singing popular and spiritual songs on the Breakfast Club and Club Matinee, popular radio programs of the wartime years. Other fine recordings of this quasi-spiritual song were made by the Golden Gate Quartet and the Song Spinners.

“Lili Marlene” became a favorite of Allied and German troops. The song’s initial popularity was the result of broadcasts by German Forces Radio to the Afrika Korps in 1941. British music publisher J.J. Phillips and songwriter Tommie Connor brought out an English version of the song in 1944. Singer Anne Shelton had the first English hit record. Vera Lynn sang “Lili Marlene” over the BBC and in concerts presented for the British Army. The well-known anti-Nazi actress Marlene Dietrich began to feature the song in 1943, to which she later added some of her own lyrics. “Lili Marlene” is possibly the most famous war song ever written, perhaps because of its global theme of dreaming for one’s love.

The song “Auf Wiederseh’n, Sweetheart,” is often included in collections of World War II songs and sheet music in error. “Auf Wiederseh’n, Sweetheart” is not a World War II love song. It was copyrighted in Germany in 1949 (Editions Corso G.m.b.H., Berlin); in the United States in 1951 (Hill and Range Songs, Inc., New York, N.Y.); and in England in 1952 (Peter Maurice Music Co., Ltd., London).

“Auf Wiederseh’n, Sweetheart” was recorded by Vera Lynn in 1951 in England with a male chorus from the British Army, Navy, and Air Force. This recording was extremely popular in the United States, where it sold about 2.5 million copies, and in 1952 Ms. Lynn became the first English artist to have a number one record. The song is still performed in the United States and England.

Lynn first heard the music for “Auf Wiederseh’n, Sweetheart” when she was on a short vacation in Switzerland from starring in a show at the Adelphi Theater in the Strand in London. While at her hotel she heard a record of children singing the song in German, and she later heard it sung at a beer garden by a German entertainer. She was impressed by the “catchy” melody and was certain it could be made into a hit record. Her many inquiries about the song were unsuccessful. Some time after returning to England, her record producer brought a number of songs to her home to review for possible recording, and “Auf Wiederseh’n, Sweetheart” was among them. English lyrics were written, and the rest is music history.

It has been written in the recent book A Century of Pop that the popular music of the United States and England reflected basic differences in raising morale during World War II. The author, Hugh Gregory, states that in Britain sentimental ballads “to inspire a stiff upper-lip determination” were used, in contrast to “up-tempo tunes” and “up-and-at-em bravado” in the United States.

In reality, the United States and England used both of the song types described. Often, songs originally written and popular in one country became hits in the other. Both countries had the same wartime objectives, produced the same types of popular songs to raise morale at home and abroad, and used music to ease fears and longing and give hope that loved ones would return safely. n

Dr. Sheldon Winkler, a professor at Temple University, has authored or co-authored five textbooks and over 160 articles and chapters in professional journals and textbooks on a variety of dental and medical topics. A former musician and the recipient of a journalism award from the International College of Dentists, Dr. Winkler is currently writing a book on the music of World War II. He resides in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments