By Peter Kross

On July 14, 1940, William Donovan stood on the pier fronting New York harbor and waited to board the Pan Am flying boat named the Lisbon Clipper for a flight that would take him to Portugal and then to London, his ultimate destination.

Donovan—a former college football star (Columbia, class of 1905), highly placed Republican lawyer, recipient of the Medal of Honor for his heroic service in World War I, a schoolmate of Franklin D. Roosevelt at Columbia University—called his wife Ruth and told her that he would be leaving that day for a trip to Europe. He did not tell her why he was going, only that it was on “private business” and that he wouldn’t be gone long. Ruth Donovan knew not to question her husband too much on his business dealings; even if she asked, he probably wouldn’t have told her anything. Among the passengers on board were two members of the French Purchasing Commission and Charles Goetz on a Portuguese arms mission.

As the Lisbon Clipper took off from New York, no one on board, even Bill Donovan himself, knew the ramifications his trip would have in the outcome of World War II. During this mission and a subsequent one he would make later in the year, the stage would be set for the formal entry of the United States into World War II and the establishment of a permanent intelligence service on the part of the United States: the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of today’s Central Intelligence Agency.

“Wild Bill” Donovan’s Fighting Irish

Just who was this most trusted man whom FDR sent on his secret mission? William Donovan was born in Buffalo, New York, on January 1, 1883. His grandparents came to the United States from Ireland and settled in Buffalo. William was the first of eight children, four of whom would die early deaths. William, his siblings, and parents lived with his grandparents in their brick home at 74 Michigan Street. He attended the Christian Brothers School and thought of joining the Dominican order but soon dropped the idea, choosing instead the law as his life’s work.

He first attended Niagara University before switching to Columbia University in New York City. William Donovan and a young Franklin D. Roosevelt attended Columbia at the same time, but the two young men were not close. At Columbia, Donovan was on both the football and rowing teams. He graduated in 1905 and remained at Columbia to get his law degree, which he received in 1907.

After graduation, Donovan returned to Buffalo to begin his law career. He joined the local firm of Love and Keating and later formed a partnership with another lawyer named Bradley Goodyear. In 1914, he married Ruth Ramsey. They would have two children, a son named David and a daughter named Patricia who died at a young age in 1940 in a car accident.

In 1911, Donovan and a number of other young Buffalo men joined Troop 1 of the New York National Guard. In 1916, he left the Army and became a member of the Polish Commission whose duties under the American War Relief Commission included the distribution of food and clothing to the needy people of Poland whose lives had been disrupted by the war.

Donovan’s National Guard unit, one of several under the command of General John J. Pershing, also saw service at home in 1916 when it was given the job of pursuing the Mexican bandit leader José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, aka Pancho Villa, who was raiding American towns in the Southwest.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Donovan, then a major, organized and led the famed 1st Battalion of the 69th New York Volunteers (the original “Fighting Irish,” and which, after the unit was federalized, was redesignated the 165th Regiment of the 42nd Division). He was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel, and his unit arrived in France in October 1917, ready for action.

Donovan, greatly admired by his men, was heroic in combat, wounded many times. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and his country’s highest decoration for valor, the Medal of Honor. He was promoted to colonel and given command of the regiment. During his wartime service, he was given the nickname “Wild Bill,” a moniker he would keep for the rest of his life.

Donovan’s Overseas Missions

Donovan used his copious political connections to break into intelligence work for the United States. In 1919, while honeymooning in Japan, Donovan detoured to Siberia on behalf of the United States government. His mission was to report the activities of the anti-Bolshevik White Russian forces under the command of Admiral Alexander Kolchak. Donovan spent two months in Siberia, often traveling with Maj. Gen. William Graves, commander of U.S. forces in Russia, who was sent by President Woodrow Wilson on a peace-keeping mission.

He spent the next six months traveling across Europe with his New York banking friend, Grayson Murphy. During his trip, Donovan kept a diary of the people and places he saw, compiling a 200-page dossier that he gave to U.S. authorities upon his return.

After completing his European sojourn, Donovan returned to Buffalo and resumed his law practice. His first job was as U.S. District Attorney for the Western District of New York. He was also active in Republican Party politics in Buffalo, running unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination for governor of New York in 1922. In 1924, Donovan moved to Washington, D.C., where he was appointed assistant attorney general by the new attorney general, Harlan Stone. He ran the criminal division from August 1924 to March 1925.

In 1929, Donovan moved to New York City and founded the law firm that would bear his name: Donovan, Leisure, Newton and Lumbard. Donovan became a wealthy man, had all the right clients, and made a name for himself on Wall Street. After his earlier unsuccessful entry into New York State politics, Donovan shifted his attention to foreign affairs.

Beginning in 1929 and ending in 1941, Donovan traveled frequently to Europe and other parts of the world as a private citizen (but with the encouragement of the U.S. government) to assess the political and military situation.

The year 1929 saw Donovan traveling across Europe and the Middle East, meeting with Mussolini in Rome, making stops in Libya, Egypt, the Sudan, and Ethiopia, and talking with the various military and political leaders in each country. Upon his return to the United States, he reported to the War Department and briefed leaders on his adventures. The material he provided to the Army staff members was first rate, and they said his data was “replete with pertinent and valuable information which the department would have been unable to secure any other way.”

Donovan also watched nervously as a German dictator named Adolf Hitler began rattling his saber at the weak nations of Europe.

In 1939, he went to Ethiopia to report on the Italian-Ethiopian war for the Roosevelt administration. He also made trips to observe the Spanish Civil War and to the Balkans and Italy. That same year found Donovan in Berlin, where he observed German military maneuvers, including tank and artillery exercises. He also made his way to the Low Countries, a possible target of Germany in the war that engulfed Poland and was threatening to spread, and met with military leaders in Belgium, Holland, and other countries.

“In an Age of Bullies, We Cannot Afford to be a Sissy”

Upon his return to the United States, Donovan engaged in a speaking campaign that alerted the American public to the war clouds gathering in Europe. Speaking to the American Legion in November 1939, he told his appreciative audience that he wouldn’t be surprised if, at some point in the future, America would have to send its boys to war. “In an age of bullies, we cannot afford to be a sissy,” he said.

Speaking about the rise of domestic spying in the United States, Donovan said that American citizens should not “be a bunch of vigilantes, but to leave the job, where it belonged—to the government.”

On November 27, 1939, in what proved to be his most important foreign policy speech to date, Donovan discussed the role of the United States in the world in a speech titled “Is America Prepared for War?” Speaking before the Sons of Erin in New York, Donovan called on all citizens, including representatives from the military, for “the creation of a civilian body of representative citizens to make an exhaustive study of the problems, and to lay its findings and recommendations as soon as possible before the President, the Congress, and the people of the United States.” One important listener to Donovan’s speech was President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

William Stephenson and the British Security Coordination Organization

Donovan’s most important champion in the Roosevelt administration was Republican Frank Knox, whom FDR appointed to be his Secretary of the Navy. As war approached, FDR wanted to staff his cabinet with a few trusted members of the Republican Party with whom he had an affiliation. Upon his appointment, Knox asked Donovan if he would be his assistant secretary, but for whatever reason Donovan turned him down.

On Knox’s advice, FDR asked Donovan to come to the White House for a meeting of some importance. Donovan was surprised to find the Secretaries of War, State, and Navy ready to meet with him. He was more surprised to learn why he had been summoned to the White House that day. He was asked by the administration to make a trip to Britain “to learn about Britain’s handling of the Fifth Column problem.”

An incident in Washington, D.C., in the spring and summer of 1940 has a profound impact on Donovan’s future relations with the British.

In the summer of 1940, William Stephenson, a Canadian businessman and, like Donovan, a decorated World War I veteran, arrived in the United States as the personal representative of newly appointed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Stephenson’s cover was that of the Passport Control Officer of the British government in the United States. He had, however, a secret directive from Churchill; he was to act as Britain’s super-spy in the United States.

Stephenson took up residence in New York City in offices near Rockefeller Center, where he began his clandestine work on behalf of His Majesty’s government. One of his directives from Churchill was to establish a clandestine intelligence arrangement between the British intelligence services and the American FBI, under the irascible J. Edgar Hoover.

In a series of hard-boiled talks with Hoover, who did not take kindly to his intelligence bailiwick being interfered with, the FBI director reluctantly agreed, upon President Roosevelt’s orders, to cooperate with Stephenson and his newly created British Security Coordination organization. FDR kept this new intelligence-sharing agreement secret, only telling a few trusted advisers, and excluded Congress from all knowledge of the arrangement.

An Unprecedented Trip to England

After returning home to report on the deal with the Americans, Stephenson contacted Donovan and brought him in on the new agreement. With Churchill doing everything in his power to persuade the United States to supply Britain with military equipment for his nation’s desperate fight against Germany, Donovan arranged a meeting between Stephenson, Secretary Knox, and Secretary of War Henry Stimson.

It was decided that a person of unquestioned character was needed for the job of U.S.-Britain secret liaison. Other candidates were considered, including financier Bernard Baruch and New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, but it was Donovan who got the position.

As Donovan flew across the Atlantic on July 14, 1940, he now entered an entirely new world from that of Republican Party politics or a Justice Department official—the world of espionage that would consume the rest of his life.

Before departing Washington, the military brass, including Rear Admiral Walter S. Anderson, director of the Office of Naval Intelligence, and Brig. Gen. Sherman Miles, head of the Army’s military intelligence under Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, sent instructions to their military attachés in England, Captain Alan Kirk and Brig. Gen. Raymond Lee, respectively, to give as much help to Donovan as they possibly could. They were told to especially facilitate any meetings with British intelligence officials with whom Donovan wanted to meet. Donovan was told that both Lee and Kirk would provide him with confidential assistance in arranging such secret meetings.

Donovan’s trip to England was unprecedented for a civilian, especially one who was not officially affiliated with the U.S. government. However, Donovan arrived with letters of introduction from some of the most prominent Washingtonians, including Navy Secretary Knox, Navy Undersecretary James Forrestal, and Rear Admiral Anderson, among others. Before his departure, Donovan dined with Lord Lothian, the British Ambassador to the United States, who put in a good word for him with his peers back home.

William Stephenson, too, pulled considerable strings with his contacts in British intelligence, asking that the British secret services give as much time to Donovan as he needed.

Meeting Stewart Menzies and John Godfrey

Besides finding out about Fifth Columnists, Donovan’s secondary purpose for the trip was to learn as much as possible about the current military situation in England. Upon his arrival, he inspected many British military installations and spoke with their commanders. He came home with a recommendation that the United States do as much as possible to aid England militarily.

His two weeks in England proved to be some of the most hectic times of Donovan’s life. Donovan was wined and dined by the establishment in the British government. He met with all the important military/ political leaders of the country, including Churchill, King George VI, and most importantly, Stewart Menzies, known as “C,” head of British intelligence. The British had hundreds of years of experience in espionage, and Menzies was eager to take Donovan under his wing.

The other important British intelligence official Donovan met with was Rear Admiral John Godfrey, head of Naval Intelligence. Godfrey introduced Donovan to his naval aide, Commander Ian Fleming, who would later accompany Godfrey to the United States to help the United States design its own intelligence service. Fleming would later use his wartime experiences when he created his fictional spy, James Bond, Agent 007.

Donovan was so impressed with Godfrey that upon returning to Washington he urged the president to appoint a person who would travel back and forth between England and the United States in a liaison capacity. He also urged full cooperation in intelligence sharing.

Negotiating Lend-Lease

During his overseas visit, Donovan listened as his British cousins asked for military help and assured Donovan that if America gave England the tools of war necessary to defend itself they would be able to stave off the Germans. Donovan was instrumental in arranging the “Destroyers for Bases” deal that sent 50 obsolescent American destroyers to England in return for the use of British bases, mostly in the Caribbean. In a report to the president that both Mowrer and Donovan would bring to FDR, they wrote, “Britain under Churchill would not surrender either to ruthless air raids or to an invasion.”

Bill Donovan left England on August 3, 1940, aboard the BOAC flying boat Clare. There were only two other passengers aboard, and upon his return Donovan would say that the trip was “boring.” Donovan arrived in New York the next evening and the following day had a meeting with Secretary Knox. Over the next few days, Donovan met with every important military and political representative of the president, including members of Congress who had been briefed on his clandestine trip.

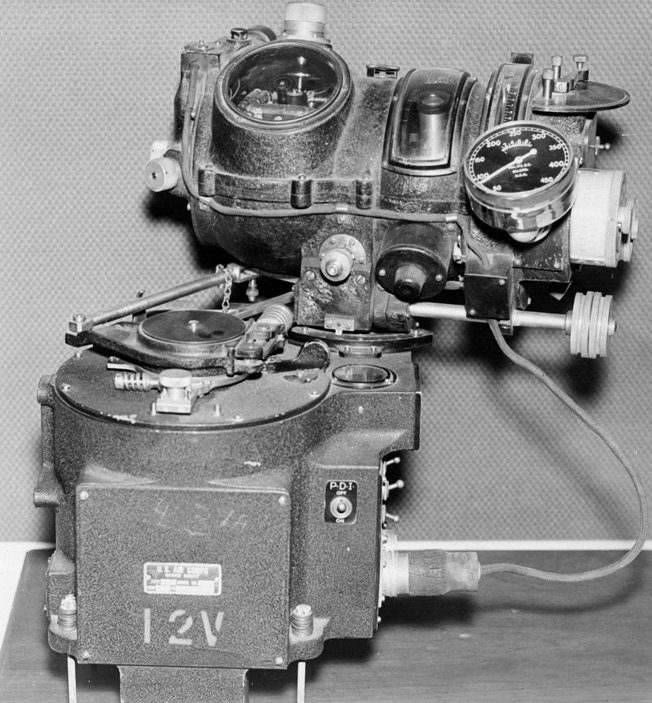

Donovan traveled with President Roosevelt to Hyde Park, New York, and in the peaceful Hudson Valley surroundings reported on all he saw and did in Britain. He told the president that in his opinion the United States should give the British all the military help necessary to win the war. He said that the British had the will and the means to beat Hitler, but they could only do it with full American support. In time, FDR agreed to provide the British with the Norden bombsight, a top-secret device that enabled Royal Air Force planes (and American ones) to bomb targets with precision. Also, millions of rifles and tons of ammunition were on their way across the Atlantic.

As far as the official reason for the English sojourn—to study Fifth Column business—Donovan and Mowrer wrote a number of articles on the dangers of such activity that were published in the nation’s press.

“Another Mysterious Mission”

Donovan’s stature in Washington began to rise, and he was referred to by some writers as a person of “mystery” and a “secret agent.” The newsmen were right in that regard, but when asked for a reaction Donovan would never respond.

What Donovan really wanted was to get back in the action in one way or another. General Marshall asked Donovan if he would be willing to inspect Army camps in the States and report on what he observed. He traveled to Fort Benning, Georgia, Fort Sam Houston, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and offered his insight.

By December 1940, a back-channel operation was going on to send Donovan on a second trip to England. There is still some debate as to who was primarily responsible for the genesis of the trip; the architect was either William Stephenson or Frank Knox. Either way, the president approved sending Donovan back across the Atlantic, and his presidential authorization was to “make a strategic appreciation from an economic, political, and military standpoint of the Mediterranean area.” Stephenson accompanied Donovan at the outset of the trip, leaving Baltimore for Bermuda on December 6, 1940. The New York Times reported that Donovan was off on “another mysterious mission.”

Due to bad weather in the Atlantic, the two men were forced to stay in Bermuda for eight days. This layover was really a boon to Donovan as far as learning how the British operated foreign intelligence. The island of Bermuda was a vital British listening post that intercepted messages from around the world (especially from Germany) coming to the Western Hemisphere. Mail arriving from Europe was intercepted and read, giving British intelligence an upper hand in tracking down Nazi sleeper rings in the Americas.

Upon his return to England, Donovan met with Churchill, who told him that he preferred to fight the Germans at their weakest points, the Balkans and the Mediterranean, in preparation for a full-scale assault against Germany proper. Donovan told the prime minister that he was asked by MI6, (the British secret intelligence organization) if he would like to take a tour of the Middle East. Churchill instantly agreed, and preparations were set in motion to send him on his way.

On New Year’s Eve, 1940, Donovan departed London on what would become a 21/2-month trip through some of the hottest spots in the British Empire, accompanied on every leg of his trip by agents of the British secret service and other government officials who opened every door for their honored guest.

Donovan’s travels took him to Gibraltar, Portugal, Bulgaria, Malta, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Palestine, Iraq, Libya, and Ireland on his way home. He met with the leaders of all the various nations and locales, with the exception of Francisco Franco of Spain who said he was too busy to see him, and French General Maxime Weygand, who was French commander in Algiers.

Under the Watchful Eye of Nazi Germany

Donovan’s trip attracted the attention of the German government, which kept a wary eye on his travels. At one point, the German press labeled his trip an “impudent” act and asked its spies to keep an eye on his progress.

An embarrassing moment for Donovan took place during his stop in Sofia, Bulgaria. German agents broke into his hotel room and stole a bag of documents that were in the open. Among the items taken from the bag were questions from the Navy to Donovan that they wanted answered. When the bag was retrieved by the police, the list of questions was missing.

The most important of Donovan’s meetings during his European trip came on June 23, 1941, when he arrived in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, to meet with that nation’s ruler, Prince Paul. This meeting took place during a time of intense military plotting on the part of Hitler and the German military.

Unknown to the world, Hitler was in the process of undoing the nonaggression pact he had made with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin and was preparing an invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa). Hitler realized that if the attack were to work he had to have a safe haven on the borders of Greece and Yugoslavia to blunt any possible British advance against Germany when the attack on Russia took place. Hitler placed intense pressure on both governments to join the Axis cause.

In his meeting with Prince Paul, Donovan tried to persuade the regent not to ally himself with Hitler, but to no avail. After the conference ended, Donovan made his way to the headquarters of General Dusan Simovic, the commander of the Yugoslav opposition to Hitler. His meeting with the rebel leader went much better than that with Prince Paul, and Donovan told Simovic that the United States would not take kindly to any nation that sided with the Germans. Donovan noted that President Roosevelt said that the United States would try to help Simovic’s cause if and when he joined the Allied side. Simovic told Donovan that his forces would resist the Germans if they attacked either Bulgaria or Greece.

When British forces arrived in Greece, Prince Paul attached himself to Hitler and Simovic overthrew Prince Paul, refuted the treaty with Germany, and installed himself as the new prime minister. Unfortunately, Hitler unleashed his powerful divisions against Yugoslavia and, by April 1941, the country was under the Nazi boot. The British then invaded Crete, and Hitler had to expend more men and time to beat them back.

The Yugoslav operations put back the invasion of Russia from May 14 to June 22, 1941. Why was this important? This delay caused the Germans to later become bogged down in the fierce Russian winter that engulfed the German troops, who were forced to fight a battle against nature that was unwinnable. Ultimately, the German Army was unprepared for the harsh conditions that engulfed it and finally led to defeat three bloody years later.

COI to OSS to CIA: The Birth of American Intelligence

Bill Donovan returned to the United States after a grueling 30,000-mile adventure on March 18, 1941, landing at New York’s La Guardia Field. He soon found himself debriefing the president and his cabinet on his whirlwind Mediterranean and Near East trip. He told his listeners that the British would be able to break the Nazi stranglehold as long as they were well equipped with the tools of war—tools that only the United States could provide.

It was also during this trip that British intelligence agents approached Donovan with the idea of a centralized American intelligence agency. Donovan presented the idea to FDR, but military leaders met it with hostility. General Miles, the head of Army intelligence, wrote to General Marshall: “In great confidence, ONI (Office of Naval Intelligence) tells me that there is considerable reason to believe that there is a movement on foot, fostered by Colonel Donovan, to establish a super agency controlling all intelligence. This would mean that such an agency, no doubt under Colonel Donovan, would collect, collate, and possibly evaluate all military intelligence which we now gather from foreign countries. From the point of view of the War Department, such a move would appear to be very disadvantageous, if not calamitous.”

Despite the military’s objections, President Roosevelt took the first tentative step in the creation of an American espionage establishment when he appointed William Donovan as head of an intelligence gathering body called COI––Coordinator of Information. The COI morphed into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) after the United States entered the war. Once the war was over, the OSS was disbanded by President Harry Truman, and in 1947 it was replaced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

William Donovan’s two trips to Europe between the summer of 1940 and the spring of 1941 helped create the alliance that won World War II and set up a permanent U.S. espionage agency that, for better or worse, has become part of the nation’s history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments