By Richard A. Beranty

In one of the most recognized photographs taken by U.S. Army cameramen during World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe, is addressing men of E Company, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 101st Airborne Division, in England on June 5, 1944, just hours before their jump into Nazi-occupied Europe. After the black and white film was developed and the photo passed censors, the image was flashed stateside to U.S. wire services for publication in newspapers and magazines. It has since been printed on calendars, coffee mugs, even a postage stamp.

As a morale booster on the homefront, the picture worked, visually depicting a determined Eisenhower and his prepared warriors on the eve of the greatest invasion ever. A common misconception took hold from the very start that the general, with his right fist clenched and thumb up, is extolling the Screaming Eagles to “Full victory—nothing else.” The men who were there, however, and who heard the general speak, including Lieutenant Wallace Stroebel, jump master and the man wearing the cardboard No. 23 indicating his landing group or “stick” in the invasion, made it known after the war that the general was discussing fly fishing with the Michigan native.

The Man with the White Nose

Most of the men in the picture have since passed on, including Stroebel, who died in 1999. But William “Bill” Bowser, 89, who lives near the groundhog-friendly town of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, remembers the general’s pep talk to the troops. At five feet, four inches tall and one of the smallest men in Easy Company, Bowser’s helmeted head and blackened face may be seen directly to the left of Eisenhower’s shoulder. And viewed at a certain angle, since multiple shots were taken of the encounter, Bowser’s nose is the “whitest” spot on his face.

“We put some kind of oil on our faces, and a buddy would take a handful of cocoa (chocolate powder) and blow it in your face,” he says. “I must have reached up and touched my nose at some point.”

Bowser says he did not hear Eisenhower’s conversation with Stroebel, but he does remember the general’s brief talk with Corporal Bill Hayes, E Company clerk, pictured directly in the center of the photograph.

“He asked Hayes where he was from, and Hayes told him either North Dakota or South Dakota. I’m not sure which,” recalled Bowser. “He then asked Hayes if he was scared, and Hayes looked over toward Stroebel and he said, ‘Yes.’ And Eisenhower said, ‘That’s okay. I’m scared.’”

The general’s apprehension is understandable. Should the D-Day operation fail, he knew responsibility would fall on his shoulders alone. He also was aware of the dire predictions made by his advisers that up to 80 percent of the airborne troops, men whom Eisenhower took a special interest in visiting on the eve of the invasion, might be lost to enemy action over the coming days.

While the casualty rate among the airborne troops came nowhere close to that estimate, the idea of sending thousands of men to possible death might explain why Army officials treated them to a hearty meal on June 5, sort of a last supper.

“Roast beef, potatoes, the whole works,” Bowser explains. “That’s when it started to dawn on us, ‘Hey, this is it.’”

The Jump on June 5th

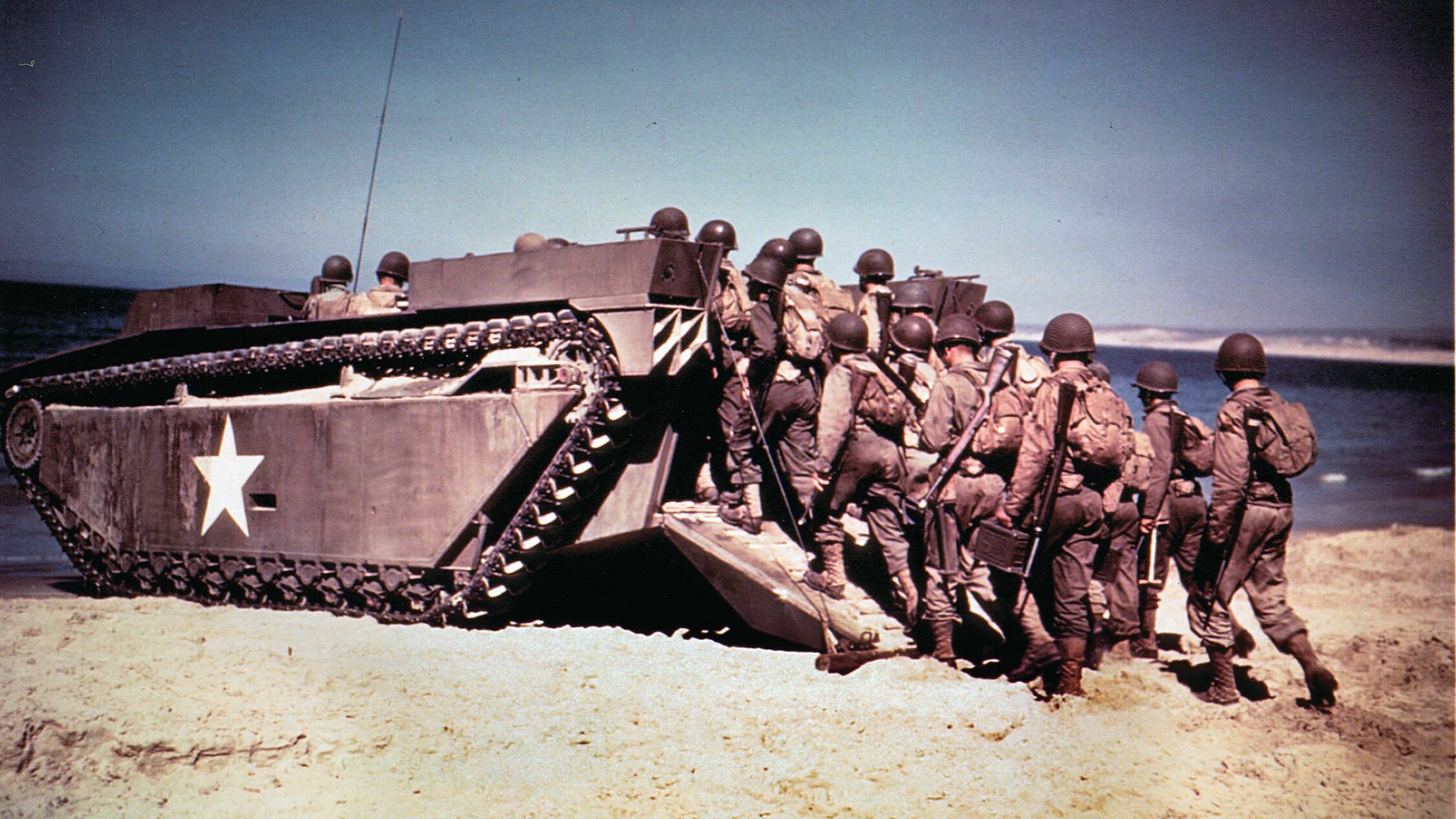

In the early evening hours of June 5, paratroops and glidermen of the U.S. 101st and 82nd and British 1st Airborne Divisions began boarding planes that would take them into the darkening skies over England and into the inhospitable darkness over Normandy.

“Officers were supposed to be our jump masters,” Bowser says. “Our plane didn’t have an officer, so the company’s first sergeant [Demitrius B. “Gus” Anagnostis, who later in the war would be awarded a battlefield commission to second lieutenant] acted as jump master. After we took off and flew a little ways, it came over the speaker for everybody to stand up and hook up because we were going to fly right between the Guernsey and Jersey Islands and were going to receive fire.”

Antiaircraft fire from the German-occupied territory in the English Channel never materialized, and about 30 minutes later Bowser and the rest of the Screaming Eagles would hurl themselves into what the division’s first commanding officer, General William C. Lee, called their “rendezvous with destiny.”

“When we got the green light to jump, the first sergeant said, ‘It’s 11 minutes after 12. Let’s get out of here,’ I was the last one in line to get out of the plane,” said Bowser. “In front of me was a kid from Philadelphia. He was our medic. And in front of him was [William F.] Podkulski. And Joe Guevera, a full-blooded Mexican, was the fourth guy. When Joe Guevera got up to the door, he sat right down in the door and Podkulski had to reach down and dump him out.”

Private Podkulski would be killed on September 22 in the battle Easy Company fought along the Wilhelmina Canal at Best, Holland, while Private Guevera would, in Bowser’s own words, “save his skin a number of times” in the war.

“When we hit the ground, there were four of us,” Bowser continues. “Nobody got hurt, and we got ready to go. Then Joe Guevera said, ‘Okay Bill, you’re the leader. You’re a corporal.’ I don’t know how in the world I ever knew which way to go. Something in me said go that way. So that’s the way I went, and it led us right to a canal.”

Capturing Carentan

Allied bombers destroyed the German long-range guns the division was ordered to neutralize as one of its first objectives in Normandy. Over the next five days and nights, the Screaming Eagles fought countless skirmishes, consolidated forces, and pushed southward.

“What sticks in my mind was the 11th of June, and that was on a Sunday,” Bowser explains. “That’s when we moved toward Carentan.”

Capturing the small Normandy town of Carentan with about 4,000 inhabitants was a high-priority assignment given to the Screaming Eagles. If left in German hands, it could be used as a corridor for a counterattack against American ground forces of the 4th and 90th Infantry Divisions moving inland from Utah Beach. Also, its main highway and railroad connected the strategic seaport of Cherbourg to the northwest, St. Lo to the southeast, and Caen to the east. Whoever controlled Carentan could conceivably control the entire Cotentin Peninsula.

While the 101st was an untested fighting force, German troops in the Carentan area included battle-experienced men of the 6th Fallschïrmjager Regiment (airborne) under the command of Major Friedrich von der Heydte. He was given orders to defend the area to the last man.

Purple Heart Lane

The main path of attack for the Screaming Eagles was a one-mile stretch of roadway that began at the south of St. Come du Mont and ended at the outskirts of Carentan. Today, this unassuming stretch of highway has been modernized, still straight and narrow, and rises only a few meters above the boggy marshes located on either side of it. But for two days in 1944, June 10 and 11, many Screaming Eagles died there and many more were wounded. So inspiring was the battle that two soldiers from Headquarters Company of the 502nd, Raymond D. Cready and Robert H. Bryant, wrote a dramatic poem of the attack that they titled “Purple Heart Lane” in memory of those who perished.

The causeway featured four stone bridges crossing canals and the Douve and Madeleine Rivers before leading into Carentan. The terrain on either side of the road prevented troops from digging in, which exposed them to direct enemy fire. Part of the plan to seize the town called for the 3rd Battalion of the 502nd, led by Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, to attack from the north straight down the causeway, in the open and without cover.

After crossing Bridge No. 1 on June 10, paratroopers found the second bridge destroyed by retreating Germans. Airborne engineers tried for hours to repair it but could not, stymied by enemy fire from mortars and 88mm cannons, one of the most feared weapons the Germans used during the war. Frustrated at their lack of progress, Cole and three others jury-rigged a footbridge with material left by the engineers. It enabled the men to cross the waterway in single file.

What followed was a slow and methodical progression down Purple Heart Lane. Screaming Eagles were extended in long columns hugging both sides of the road and were under sporadic fire from enemy artillery. That changed dramatically when the men reached Bridge No. 4, blocked by a massive iron and concrete Belgian gate that the troopers could open only about 18 inches, allowing just one man through at a time.

Here, German fire increased greatly. Snipers and machine guns opened up from the front and on both sides of the causeway. For several hours, 3rd Battalion men, clinging to both sides of the road, were mauled badly and picked off at an alarming rate. Only a handful managed to squeeze through the Belgian gate, cross the bridge, and flop in a ditch, pinned down with a 200-yard open field facing them.

This fourth bridge, built of stone, still stands today, located just off of the road that leads into Carentan.

The American attack petered out, and mercifully division artillery and the Normandy darkness halted the carnage, that is until around midnight when two enemy planes from seemingly out of nowhere bombed and strafed the battalion huddled along the causeway. The bleeding and dying troopers were left where they had fallen. The destroyed second bridge prevented wounded from being taken out and reinforcements from being brought in.

Cole’s Charge

Colonel John H. Michaelis, 502nd regimental commander, was quick to order Cole to renew the attack on Carentan. The antsy Cole, always eager for a fight, gladly obliged. At 4 am on June 11, under cover of darkness and during a break in enemy fire, paratroopers began moving through the Belgian gate and across the fourth bridge. The men made it to an open expanse of farmland when German fire erupted again. It came from a farmhouse and outbuildings owned by the Ingouf family, which were being used by Major von der Heydte as his headquarters. The Americans who crossed the bridge were hung out to dry along the field and unable to advance. Cole called for division artillery to target known enemy positions. It had little effect, and the German guns continued to fire.

Faced with the destruction of his battalion, Cole made a desperate decision and ordered a bayonet charge on the farmhouse, a rarity in World War II. His order was relayed to Major John P. Stopka, 3rd Battalion’s executive officer. Under cover of a smoke screen, Cole blew his whistle and rose to his feet. Some accounts report he held and fired his .45-caliber pistol as he charged. Others say he picked up a fallen man’s M1 Garand rifle and affixed a bayonet during the assault. Of the approximate 250 paratroopers who should have followed him, only about 20 did so because of confusion and poor communication. Some 50 followed Major Stopka. The attack became known as Cole’s Charge, and according to author and military historian John C. McManus, the bloodshed was horrendous.

“Cole and the others at the front of the charge had made it across the open area (roughly the length of two football fields), closed with the Germans in the Ingouf farm and either killed them or put them to flight. The Americans howled like demons as they charged. It was grisly—warfare at its most elemental. Dead and dismembered Germans lay everywhere—in foxholes, behind embankments, outside the farm buildings and behind hedgerows. Very few of them had been bayoneted, although some had. Most had been killed by rifle fire or grenades at close range. The rest were retreating west, in the direction of the Cherbourg-Paris railroad. First Sergeant Kenneth Sprecher [who would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions] and Private George Roach shot the lock off the door of the main farmhouse and charged inside, only to find the place abandoned. Cole followed and used the place as his command post.”

“Fix Bayonets”

Warfare is fraught with the mixing of units, and Bowser, a member of 2nd Battalion, found himself with Major Stopka and 3rd Battalion during the charge. His crossing of Bridge No. 4 was not through the Belgian gate. He crossed the Madeleine River underneath the span.

“We had a column on each side of the road, and we went to the fourth bridge and that’s where we stopped,” he says. “The Germans were covering the bridge with small arms. We went down under the bridge, and there was a jump rope. Someone ahead of us put that jump rope there, and I was the first one to use it. I threw my rifle over my shoulder and jumped and went head over heels into the water. The river was deeper than we figured.

“We stayed under that bridge on the bank. What stands out is there was an 88 that came whistling over us. I was assistant squad leader, and I had positioned myself over this machine gun. Another 88 came and I said, ‘That one’s carrying the mail.’ So we hit the ground, and I landed between the gunner, [Joseph] Malliawski, and the assistant gunner, who was a German-born barber from New York. Then Malliawski said, ‘There’s something in my shoulder.’ I looked, and I said, ‘Yea, there’s a piece a steel.’ He said to pull it out. So I pulled it out. It was about an inch long, but he wasn’t bleeding much. I never reported it, so he never got a Purple Heart. Malliawski was the only man who saw every day of combat in our company. If I had known, I would’ve let the medic take care of it, and he would’ve gotten the Purple Heart.”

Shortly afterward, Cole gave his order to charge.

“The units were badly mixed up, but it was mostly Cole’s outfit. We started to advance, and the Germans had us pinned down in an open field and the only place I could get to was a dead furrow, a deep ditch,” recalled Bowser. “They pinned us down there, and I was head to head to my squad leader, Sergeant [Robert E.] Pope, and I said, ‘What do we do now?’ He said, ‘I don’t know. Let’s have a smoke.’ So he lit a cigarette and tore it in two. My half was all soaking wet. And the first thing I can recall is that an order came down the line, all the way from Cole: ‘Fix bayonets.’ So we fixed bayonets, and on Cole’s command, ‘Everybody up and at ’em.’ And we went in. But the Germans didn’t stay to fight. They left. Then we kept driving into Carentan. To this day I don’t know whether we got credit for taking Carentan, or if the 506 (Parachute Infantry Regiment) did.”

Recalling his participation in Cole’s Charge reminds Bowser of an incident that had taken place two years earlier. “I remember in basic training, it was hot and everybody was tired. We were training for a bayonet charge. I made the mistake of saying that was from World War I, why do we have to take bayonet training? For that I went down and did push-ups.”

Carentan was liberated by the 101st on June 12. For his heroic actions on June 11, Cole was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but he did not live to receive it. On September 18 in Holland, he was on the radio with an Allied pilot who requested that orange panels be placed in front of American lines near Best to indicate airborne positions. Cole did it himself and was shot dead by a German sniper. His family was presented his Medal of Honor posthumously. Cole’s body is interred at the American Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands.

Stopka was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Carentan. He replaced Cole as commanding officer of 3rd Battalion. Stopka was killed on January 14, 1945, near Michamps, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge, when American planes bombed his position by mistake. His body is buried at the Luxembourg American Cemetery near Hamm, Luxembourg.

Easy Company’s Market-Garden: The Battle for Best

Easy Company of the 502nd fared better than many other airborne units during the Normandy operation. From June 6 until its return to England in July, the company lost three men killed in action. Bowser says the next two months were a period of training and refitting for the Screaming Eagles in preparation for their second and last combat jump of the war, this one into Holland.

Code-named Operation Market Garden and developed by British General Bernard L. Montgomery, Allied paratroops were dropped along a corridor in Holland to seize roads, bridges, and the cities of Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem, which would cut the country in half and clear a path for British armored and mechanized units to enter Germany from the north. If all went according to Montgomery’s planning, it could bring the war to a swift end, possibly by Christmas. The goal of the 101st was to secure a 15-mile stretch of road from Eindhoven to Veghel, which became known to those who fought there as Hell’s Highway.

On September 17, thousands of Allied paratroops and glidermen made a daylight landing in Holland and quickly began to consolidate. The 502nd landed at 1:30 pm. It took only one hour and 10 minutes for 97 percent of the regiment to assemble. In Normandy, it routinely took half a night to gather six men.

Still under the command of Colonel Michaelis, the 502nd received orders to seize the small road bridge over the Dommel River, capture the little town of St. Oedenrode, then secure the railroad and highway bridges that crossed the Wilhelmina Canal at Best. With its first two objectives reached, the men began their approach toward Best through the Zonsche Forest, an area thick with closely grown fir trees. Enemy troop strength in the area was thought to be light, and the Germans who defended it of poor quality— kids and old men. For that reason only a platoon was sent at first to capture the bridges. When German resistance intensified, a company was called in to help. Before too long, the effort included the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 502nd along with a column of British mechanized vehicles.

The paratroops had fought their way to within 100 yards of one of the bridges when German engineers blew it up. It was an ominous sign that the battle for Best would be the most violent of the war for men of the 502nd, especially for the regiment’s officers. On September 18, Cole was cut down by a sniper’s bullet. Michaelis and three of his staff were seriously wounded on September 22 by enemy artillery outside his command post. Lt. Col. Steve A. Chappius assumed command of the regiment. Captain Fred O. Drennan, commanding officer of Easy Company and recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross, was killed on September 22. Captain James J. Hatch took charge of the company.

Another noteworthy death in the 502nd at Best was Pfc. Joe Mann, an Oregon native, of 3rd Battalion’s H Company. Already wounded twice in the Zonshe Forest, on September 19 he threw himself on a German grenade to shield the other men inside of his foxhole from the explosion. Like Cole, Mann was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. They were the only two Screaming Eagles in World War II to receive the medal.

Easy Company lost 18 men killed in action at Best; 12 had been with the company during its jump into Normandy. The early fighting in Holland was bittersweet for the 502nd. While 1,100 prisoners were taken at Best and the fight was presumably won, the regiment was moved north toward St. Oedenrode to take up defensive positions to help keep the supply lines open along Hell’s Highway. This movement allowed much of the ground that the regiment fought so hard to take to fall back into enemy hands.

Bill Boyle’s .45

Over the next two months, the Dutch countryside became a muddy and wreckage-strewn plain as German units tried again and again to disrupt the flow of men and machines toward Arnhem.

“One night along the Wilhelmina Canal,” Bowser recalls, “our second in command at the time was Lieutenant [James W.] Tolar. And [Pfc.] Bill Boyle was wounded bad. Lieutenant Tolar said, ‘There’s a boat. Take Boyle and any other wounded and see what you can do for them.’ Well, now as I tell that story, what in the world! I don’t know where to go, what direction! But you don’t think. You go! Bill Boyle was bad, and he took out his pocketbook and he had a .45-cal. [pistol]. He gave me his pistol and the pocketbook and said, ‘See that my mother gets my pocketbook.’

“We got in the boat and went to the other bank. We were going down the canal, and I heard an engine running. So I stopped. The engine stopped right above us. We were all real quiet, and I heard English, British. We made ourselves known, and they took us, turned their vehicle around, and went back the way they had come. We turned in Bill Boyle with the other wounded. We rode quite a ways on that British vehicle, and I didn’t get back to my company for what must have been two days. When I met up with them, I went over to F Company to see if a buddy from Punxsutawney was living, [Edward A.] Lefty Jacobson. He was.

“After supper that day, after five o’clock, the Germans started to surrender, 1,100 of them total. Old men and young kids. We had to search everyone and turn them over to some people to take them back.”

Throughout October and into November, the Screaming Eagles, men who were trained to parachute behind enemy lines, disrupt and engage the enemy with speed and surprise—the cutting edge of attack warfare—now found themselves as “normal” soldiers holding defensive positions. Probes into the German-occupied Dutch countryside became the norm.

“One of our cooks wanted to go on a patrol with us,” Bowser says. We had men on either side of the canal, and we were keeping track over the telephones so that one squad didn’t get ahead of the other. This cook was never on a patrol, and he just begged, so they took him. And he wanted to carry Bill Boyle’s pistol, so I let him. When we lost communication, Lieutenant Tolar said to me, ‘Bill, you go up on the dike and keep us together.’ I said okay, and the Germans must have seen me because an 88 went over me. The next one, I didn’t have time to do anything, only to hit the ground, and I knew it was carrying the mail. It landed about 20 yards in front of me, and I never got a scratch.

“The squad on the right side went into an apple orchard, and the Germans had set booby traps all through that orchard. The cook stepped on one, and it blew him up. Parts of him were up in the trees. I never saw that pistol again. But I was able to give Bill Boyle back his pocketbook. I heard from him once [after the war], but he died quite a long time ago.”

Defending Bastogne with White Sheets

In late November, the Screaming Eagles were taken off the line and trucked to their base camp at Mourmelon, France. Their period of rest and refitting did not last long. On December 16, after secretly assembling a massive army of men, artillery, and armored units in the forested Ardennes region of Belgium, the Germans struck American lines with complete surprise. One of their first goals was to capture the Belgian town of Bastogne, an important road and rail center.

The Nazi offensive quickly overran American defenders, which included battle-tired and inexperienced troops positioned in the area because the terrain was considered unfit for a German offensive. Eisenhower was stumped on how to plug the tidal wave. At one point he considered breaching the Army’s segregation policy and placing black soldiers on the front lines, but that never happened. To stem the onslaught, he sent the 82nd and 101st Divisions to the area by truck, hoping that these elite and veteran outfits, which were now at full strength and well acquainted with isolation as combat formations, could pull off a miracle.

With General Maxwell D. Taylor at a staff conference in the United States, command of the 101st fell to General Anthony C. McAuliffe, head of the division’s artillery. During the evening of December 17, the 101st received orders to proceed to Bastogne. The lone standing order McAuliffe received from VIII Corps commander General Troy Middleton was direct: “Hold the Bastogne line at any cost.” The 101st made the 107-mile journey in open 10-ton trucks.

“They told us to go and draw ammunition,” Bowser says. “Nobody knew where we were going. I took my overcoat and six-buckle Arctics [boots]. When we went into Bastogne our company made a circle around the town. I’m not sure who was on our left or right flanks. Snow was knee deep and the Germans had white camouflage uniforms. Once in our foxholes, you had to have one guy awake all the time.”

Following one heavy snowfall on December 22, Major John D. Hanlon, who commanded the 1st Battalion, 502nd, asked the villagers of Henroulle, Belgium, for white sheets to camouflage men and vehicles. In 1948, Hanlon returned to the village with a gift from the people of his hometown—replacement sheets.

Speed to the front lines was critical if Bastogne was to remain in American hands. Just two days after the Screaming Eagles departed Mourmelon, they were dug in and positioned in all directions around the town, with the 502nd in the area of Longchamps on the northwest side of the perimeter. On December 20, German troops isolated Bastogne and the 101st by seizing the last road leading out of town. The Americans were surrounded for the next seven days. Their position must have seemed hopeless to the Germans, as on December 22 they delivered an ultimatum under a white flag to the besieged troopers: surrender or be annihilated. To that, McAuliffe gave his famous “Nuts” reply.

The “Battered Bastards of Bastogne”

The siege was lifted at 4:45 pm on December 26, when the lead tank of the 4th Armored Division met a 101st Division roadblock on the southern perimeter of Bastogne. The wary troopers manning the roadblock kept the tank crew at gunpoint until they were sure it was not a German trick. But by no means did it mean an end to the fighting. During the freezing weather over the next three weeks, the division would suffer through some of the toughest and bloodiest fighting of the Ardennes campaign. During a German push on 502nd lines by SS Panzer units on January 3, Bowser was wounded.

“We had been over a hill, and when they started to attack we ran to where our section was, our foxholes. When the German tanks started over the hill, we got orders not to fire until the last soldier is down off of that hill. Then mow them down. I was a sergeant at that time, and I was going from foxhole to foxhole to see how the guys were getting along. I went into one foxhole, it was a tee, and the gunner who I didn’t know was dead. I could see blood gushing down from his chest. I went to another hole, and I looked down and saw blood on my left leg. There were two guys in there, replacements I didn’t know. One was pretty bad from artillery. He had a phone, and I called back to Lieutenant [Bernard J.] McKearney and said, ‘We’re going to need more ammunition, we’re getting low.’ That’s when I found out that I was wounded. My wound wasn’t bad, and neither was one of the other guy’s. So we helped this one guy over to the company’s command post. When we got there, there were medics and wounded guys lying all around.”

The “bulge” in the American lines was eventually reduced. On January 18, 1945, enemy resistance ended and the Screaming Eagles received a “receipt” from VIII Corps command and signed by General Middleton. It read: “Received from the 101st Airborne Division, the town of Bastogne, Luxembourg Province, Belgium. Condition: Used but serviceable.” On the following day, the “Battered Bastards of Bastogne” were relieved.

Bowser and Easy Company after Bastogne

Due to his wound, Bowser would not meet up with Easy Company again until April 1. During his absence, the Screaming Eagles returned to Mourmelon, where Eisenhower presented the division with the Presidential Unit Citation for their defense of Bastogne. It was the first time in the history of the U.S. Army that an entire division was given the citation. Previously, it had been awarded to units of regimental size or smaller.

The final combat mission of World War II for the 101st was to capture Hitler’s mountaintop retreat at Berchtesgaden, known as the Eagle’s Nest. Occupation duty in Germany followed, which left many troopers with plenty of time on their hands. Despite the Army’s non-fraternization policy, many of the men found themselves with a lot of pent-up energy and had to let loose.

“One guy in our platoon knew he could get booze from a house in this little village,” Bowser says. “He got it there before. So he went back and the door was locked. I don’t know how long he waited, but he figured he’d shoot the lock off the door. So he did, shot into the house, and he hit an old woman who lived there and killed her. I don’t know how long afterward, but the family was trying to find him. They must have seen him around. So we had a company formation, the same as always, and our platoon sergeant saluted the company commander and said all present or accounted for. The family went up and down the lines, but this guy wasn’t there. The platoon sergeant put him back in the kitchen so he couldn’t be identified.”

Those Screaming Eagles who had earned the required 85 points for discharge departed Europe from the southern French port of Marseilles on September 6, 1945, and arrived in Boston harbor eight days later. Bowser was discharged from the Army at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, and went home to Punxsutawney. The future gas field worker is quick to explain that the lure of an extra $50 in jump pay was his incentive to go airborne. Would he do it again?

“No. As far as money goes, it didn’t do me any good.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments