By Flint Whitlock

By any standard, the ancient city of Rouen, in Upper Normandy, is a historical treasure. Within its magnificent High Gothic Notre-Dame Cathedral (which was portrayed in a famous series of paintings by the Impressionist Claude Monet as well as by his contemporary Camille Pissarro) is a tomb containing the heart of Richard the Lionheart (1157-1199) who had been King of England and the Duke of Normandy. A few streets away is Vieux-Marché, the place where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake on May 30, 1432. Unfortunately, like many French cities that felt the weight of the Allied bombing of France during the course of the war, Rouen was particularly hard hit. The city on the Seine, which existed even before the Romans reached Gaul, was and is a tangle of narrow, winding streets lined with quaint, half-timbered, medieval homes and shops.

Many books and articles about World War II tend to focus solely on the battles, the movement of troops, and the territories won and lost. Several recent books have given us a picture of what life was like for the German people in the wake of defeat. But not many dwell on the impact of the war on the French people who, after all, bore the brunt of two invasions—the German invasion in 1940 and the 1944 invasions in Normandy and the Riviera by the liberating Allied armies. And even fewer works concentrate on the suffering caused by American and British aerial bombing.

The Allied Bombing of France

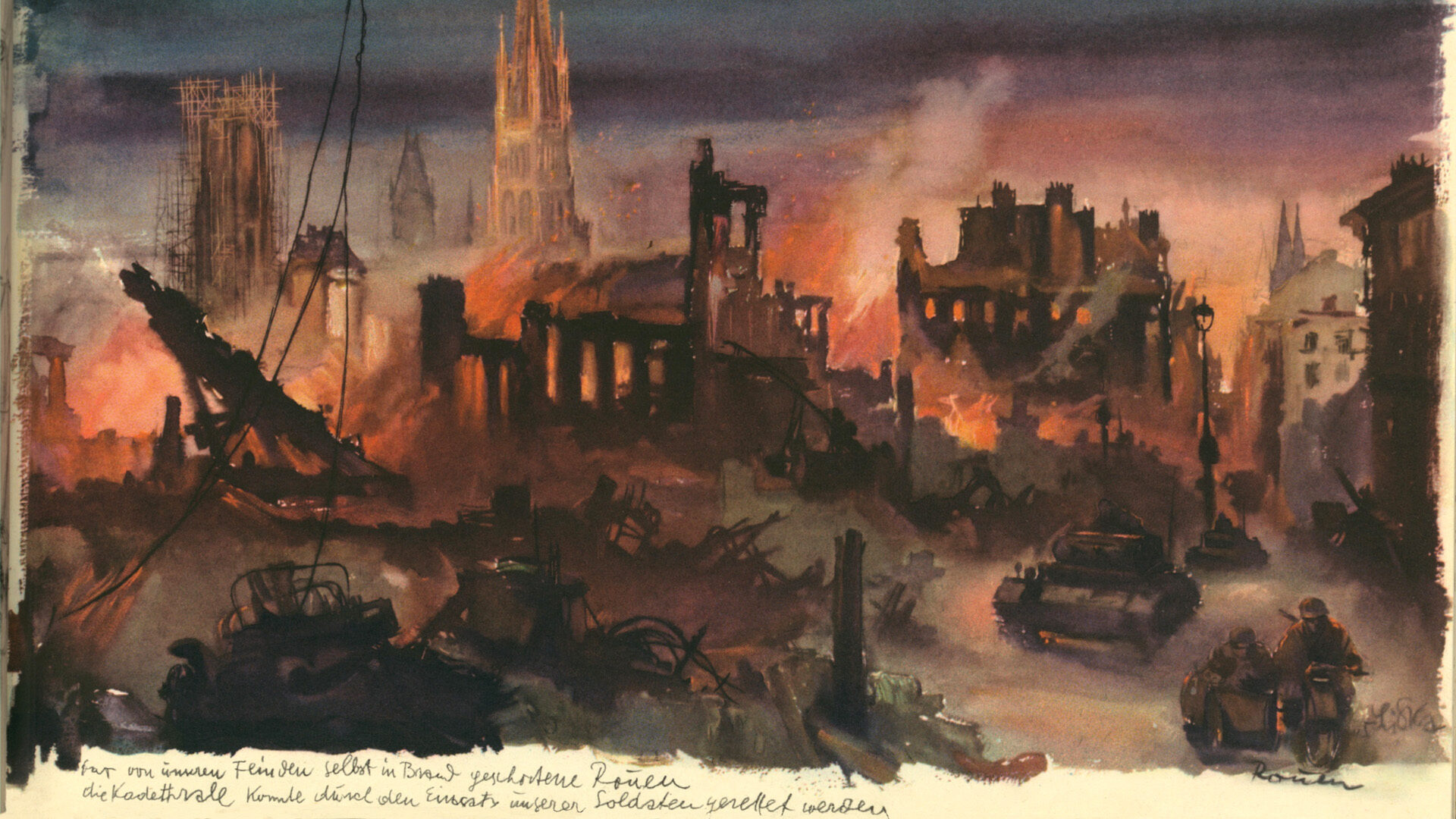

The Allied bombing of France began with the British, shortly after its capitulation and occupation by the Germans in June 1940. As French Army units pulled out of Rouen and retreated westward, they dynamited the bridges over the Seine; the German 5th Panzer Division moved in and claimed the city on June 9.

On June 11, a large fire of unknown origin broke out in the old city between the Notre-Dame Cathedral and the Seine River. The Germans did not allow firemen access to the fire, and the city burned for 48 hours, destroying some 900 buildings dating from the 14th century.

Following its fall, Rouen, then a city of about 120,000, was quickly turned into a German logistics and administration center where the occupiers located numerous commands. For example, Feldkommandatur 517, the administrative headquarters for the region, was established there along with a variety of supply depots, a pay and administration center, and offices for transportation coordinators. In the western suburb of Canteleu were the headquarters of LXXXI Army Corps. Two antiaircraft battalions were supposed to protect Rouen from aerial attack.

To cross the Seine, at least two temporary bridges were built by the Germans to replace the ones the retreating French had destroyed. With its extensive harbor facilities 35 miles inland from the estuary of the Seine at Le Havre, Rouen was one of France’s most important shipping ports. In fact, Germany planned to use it as one of its springboards for launching Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of Britain. A number of maritime repair facilities in Rouen were used to maintain Kriegsmarine vessels, and the navy’s Channel Coast Command had its headquarters there.

Furthermore, the southern suburb of Sotteville-lès-Rouen was a major regional railroad hub that enabled the occupiers to shuttle troops from Germany into France. Major telephone-telegraph lines also ran through Sotteville, making the Rouen-Sotteville area a vital communications center.

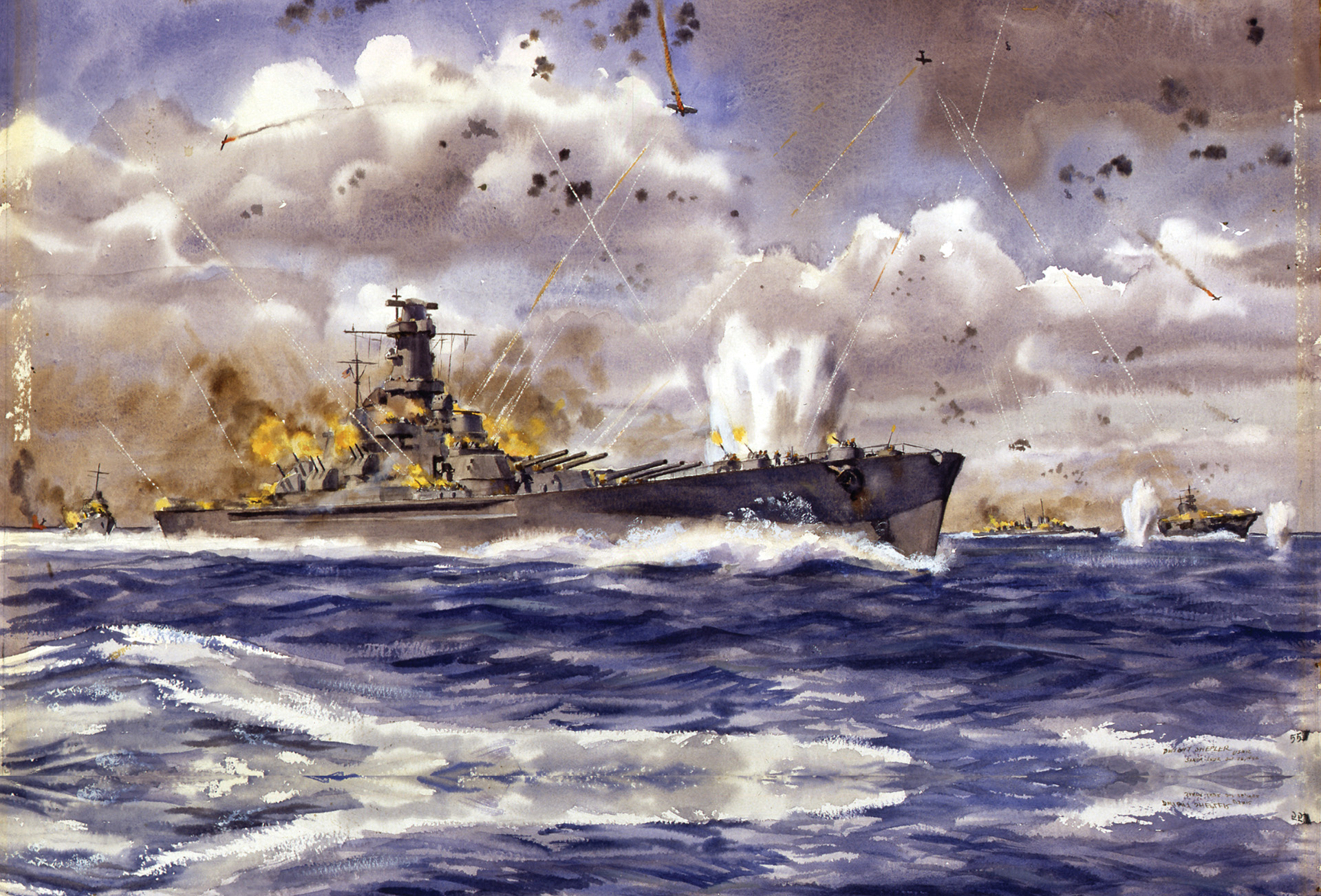

After the United States entered the war, it was decided in early 1942 to establish American air bases in Britain so that the U.S. Army Air Forces could join the British in bombing the Continent. It took months before that could happen—bases had to built, bombers and bombs had to be brought from the States, and personnel had to be trained.

Most of the targets, of course, were supposed to be strictly military: German supply bases, submarine pens, shipyards, bunker complexes, V-1 launching sites, railroads, bridges, and highways the Germans used to shuttle troops to various locations. Manufacturing plants producing goods for the occupiers in France were also targeted. But planned targets do not always translate into bull’s-eyes, and bombs do not discriminate between friend and foe.

The Americans also wanted to devote their efforts to daylight bombing—something the Royal Air Force had already tried and abandoned due to unacceptable losses in aircraft and personnel. The Americans were confident that they could succeed at daylight raids, thanks to the Norden bombsight and the more heavily armed B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators.

The official U.S. Air Force history says, “The subsequent bombing of Germany by the RAF had as yet been conducted on a scale too limited and in a manner too specialized to answer conclusively the opponents of air power. As for the USAAF, its doctrine of daylight bombardment remained entirely an article of faith as far as any experience in combat under European conditions was concerned.”

Some Brits were highly skeptical. One British newspaper reporter for the Sunday Times scoffed that “American heavy bombers—the latest Fortresses and Liberators—are fine flying machines, but not suited for bombing in Europe. Their bombs and bomb-loads are small, their armour and armament are not up to the standard now found necessary, and their speeds are low.”

First Sortie on Rouen-Sotteville

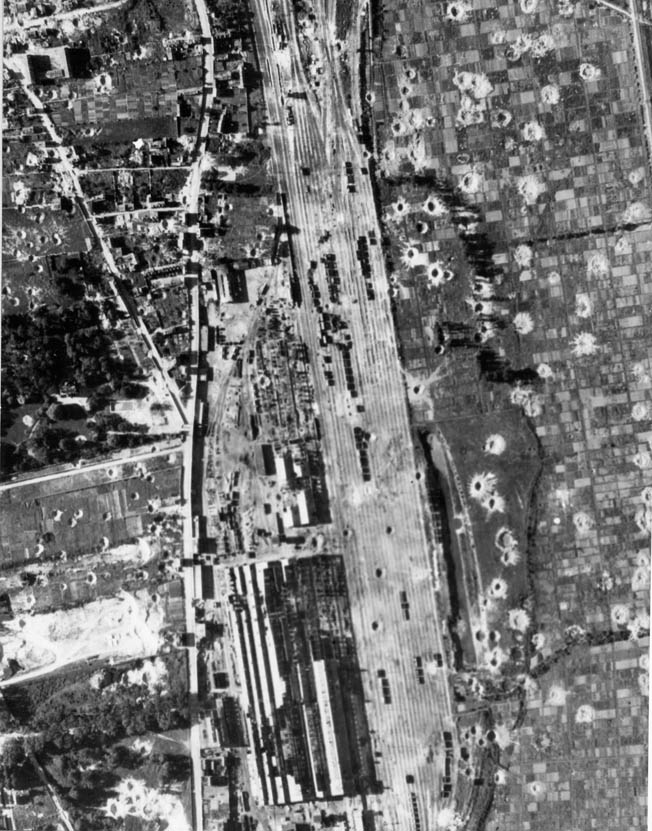

Determined to prove the skeptics of daylight bombing wrong, finally, in August 1942, Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker’s VIII Bomber Command was ready. The first Flying Fortress sortie against Europe was the 97th Bombardment Group’s mission to hit the rail-marshaling yard at Rouen-Sotteville on August 17, 1942. An earlier mission scheduled for August 10 had been scrubbed due to bad weather and heavy cloud cover over Rouen.

The Air Force history continues: “So it was that on 17 August 1942 all eyes were fixed on a bombard-ment mission which in the later context of strategic bombing would have appeared insignificant indeed. The experiment begun on that day culminated during the following year in the Combined Bomber Offensive, a campaign which could only have been attempted after all major doubts regarding the use of heavy bombardment forces had for practical purposes been removed.”

The raid on Rouen-Sotteville was an admittedly small effort: 18 B-17Es (six of which would fly a diversionary sweep along the coast) accompanied by four squadrons of Spitfire IXs lifted off at 3:30 pm from RAF Grafton Underwood in Northhamptonshire. Piloting the lead aircraft of the group, Butcher Shop, was Major Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., who would later pilot the Enola Gay on the first atomic bomb mission to Hiroshima, Japan, while the group commander, Colonel Frank A. Armstrong, Jr., one of Tibbets’ squadron commanders, was co-pilot.

General Eaker was flying in the lead plane of the second flight of six, nicknamed Yankee Doodle. Inside the 12 bombers destined for Rouen-Sotteville were 36,900 pounds of bombs; nine of the B-17s carried 600-pound bombs, while three others carried 1,100-pound bombs intended for the locomotive workshops.

A little more than three hours later, as the formation approached the target at 23,000 feet without arousing enemy flak or fighters, Eaker moved from his position in the radio compartment to the bomb bay to watch the 600-pound bombs descend on Sotteville and its “long lines of railroad track crowded with freight cars surrounded by locomotive repair shops, factories, and sheds.”

Eaker watched as the formation’s 18 tons of bombs got smaller. “As each plane’s bomb load reached its mark,” the general said, “a lofty, mushroom-like pall of smoke and dirt rose sluggishly into the air and clearly identified the point of impact.

“The tallest of these giant mushrooms was within the central target area; two appeared to engulf the roundhouse while four were well spaced among the tracks of the marshaling yard…. The bombing, I thought, was especially good.”

Despite attracting some German fighters on the way out, the bombers returned to their base without losing a plane. Maj. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, commanding general of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, told a newspaper reporter, “It is only the start. We expect to keep up these raids. Everything went according to plan.”

Spaatz also telegraphed his boss, Henry “Hap” Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces, in Washington: “The attack on Rouen far exceeded in accuracy any previous high-altitude bombing in the European Theater by German or Allied aircraft. Moreover, it was my understanding that the results justified ‘our belief’ in the feasibility of daylight bombing.” Thus was the myth of “precision daylight bombing” born.

But there was nothing precise about the August 17 raid. Only about half the bombs fell in the rail yard; the rest hit the commercial and residential areas around it, killing 52 civilians and wounding 120.

On the day after this first mission, Air Marshal Sir Arthur T. “Bomber” Harris, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, RAF Bomber Command, sent a message to Eaker: “Congratulations from all ranks of Bomber Command on the highly successful completion of the first all-American raid by the big fellows on German-occupied territory in Europe. Yankee Doodle certainly went to town and can stick yet another well-deserved feather in his cap.”

High praise, but Harris was careful not to mention the mission’s shortcomings. The U.S. Air Force official history also downplayed the errors: “The bombing was fairly accurate for a first effort. Approximately half of the bombs fell in the general target area. One of the aiming points was hit, and several bombs burst within a radius of 1,500 feet. Those intended for the other aiming point fell mostly about 2,000 feet to the south.

“Fortunately, the yard and adjacent facilities presented a large target, so that even technically inaccurate bombing might still be effective. Nevertheless, it was surprisingly good bombing. And it was effective enough, considering the small size of the attacking force.

“Direct hits were scored on two large transshipment sheds in the center of the marshaling yard, and about 10 of the 24 tracks on the sidings were damaged. A quantity of rolling stock was destroyed, damaged, or derailed. As it happened, activity in the yard was not at its peak when the attack occurred, or destruction of rolling stock might have been much greater.

“Damage to the tracks no doubt interfered with the flow of traffic, but a sufficient number remained undamaged…. The bottlenecks at each end of the sidings were not damaged. The locomotive workshop received one direct hit which probably slowed up the working of locomotives and other rolling stock in and out of the building quite apart from the constructional damage resulting from blast.”

The history concludes, “It was clear that a much larger force would be required to do lasting damage to a target of this sort. But for the time being, the extent of the damage inflicted was less important than the relative accuracy of the bombing.”

Much larger forces would follow shortly.

Continuing the Bombing Campaign Against Rouen

On September 5, 1942, the Americans returned to hit Rouen-Sotteville again. This time, 31 B-17s attacked, but their accuracy was even worse than on the first raid; less than 20 percent of the bombs struck the rail yard. And this time civilian casualties were even greater: 140 killed and 200 wounded.

Stephen Borque, a historian who has studied the Allied bombing of France, noted, “Free French leaders, who the Allies would need to govern postwar France, were angry over the bombing of French cities and towns and the growing toll of civilian casualties.”

Six months later, on March 12, 1943, American raiders struck Rouen-Sotteville for a third time, from 25,000 feet. The mission report from the 91st Bomb Group (Heavy) says it was “the perfect mission. First time Spitfire escorts kept enemy fighters at arm’s length while group bombardiers executed their runs in peace. Inbound diversionary pattern, then target was destroyed. 91st put up all 18 flyable forts.” (The famed B-17 Memphis Belle took part in this raid—her 14th.)

Sixteen days later, another mission, this time by 79 B-17s and 24 B-24s, took off to hit Rouen-Sotteville once again. All the B-24s turned back because of bad weather, but the B-17s continued on, dropping 209 tons of bombs on or near the rail yards. One B-17 was shot down, and three others were damaged.

Michel Leveillard, then 11 years old and living in Rouen, said, “Although I cannot be absolutely certain, I believe I saw that airplane go down since it was the first B-17 shot down over Rouen, and because that day we saw no parachutes, and we had a lull period with no heavy bombardments following that one until July…. I sure have vivid memories of all the 100-plus bombings of my hometown.”

After July, raids continued intermittently. On August 25, 1943, B-26 Mitchell Marauders from the 386th Bombardment Group (Medium), based at Snetterton Heath, hit the power plant at Rouen. Then, well before dawn on Monday, September 6, 1943, the same 386th was briefed on “Mission Number 14”—target identification Z435: the marshaling yard at Sotteville-Rouen. Forty B-26s would each carry 500-pound general-purpose bombs and rendezvous with another B-26 bomb group, the 387th, coming from Chipping Ongar.” The combined planes in the formation would be escorted by 10 squadrons of Spitfires.

The raid went well. After the mission, the 386th’s historian noted, “The formation neared the I.P. [Initial Point] at Blainville as a few rounds of inaccurate 88mm flak came up just as the formation made a right turn to commence their bomb run at 10,500 feet. Black puffs of flak appeared as it was bombs away at 0748 hours. Bomb strikes were observed at the north end of the rail yard in the midst of tracks and buildings, with results from fair to good.

“The 386th second box … released their bombs from 9,300 feet with good results. [The commander’s] crew reported seeing a big flash of red flame when their bombs erupted on the target.”

The B-26s made it back to their bases without the loss of a single plane. But the U.S. Army Air Forces were not yet finished with Rouen.

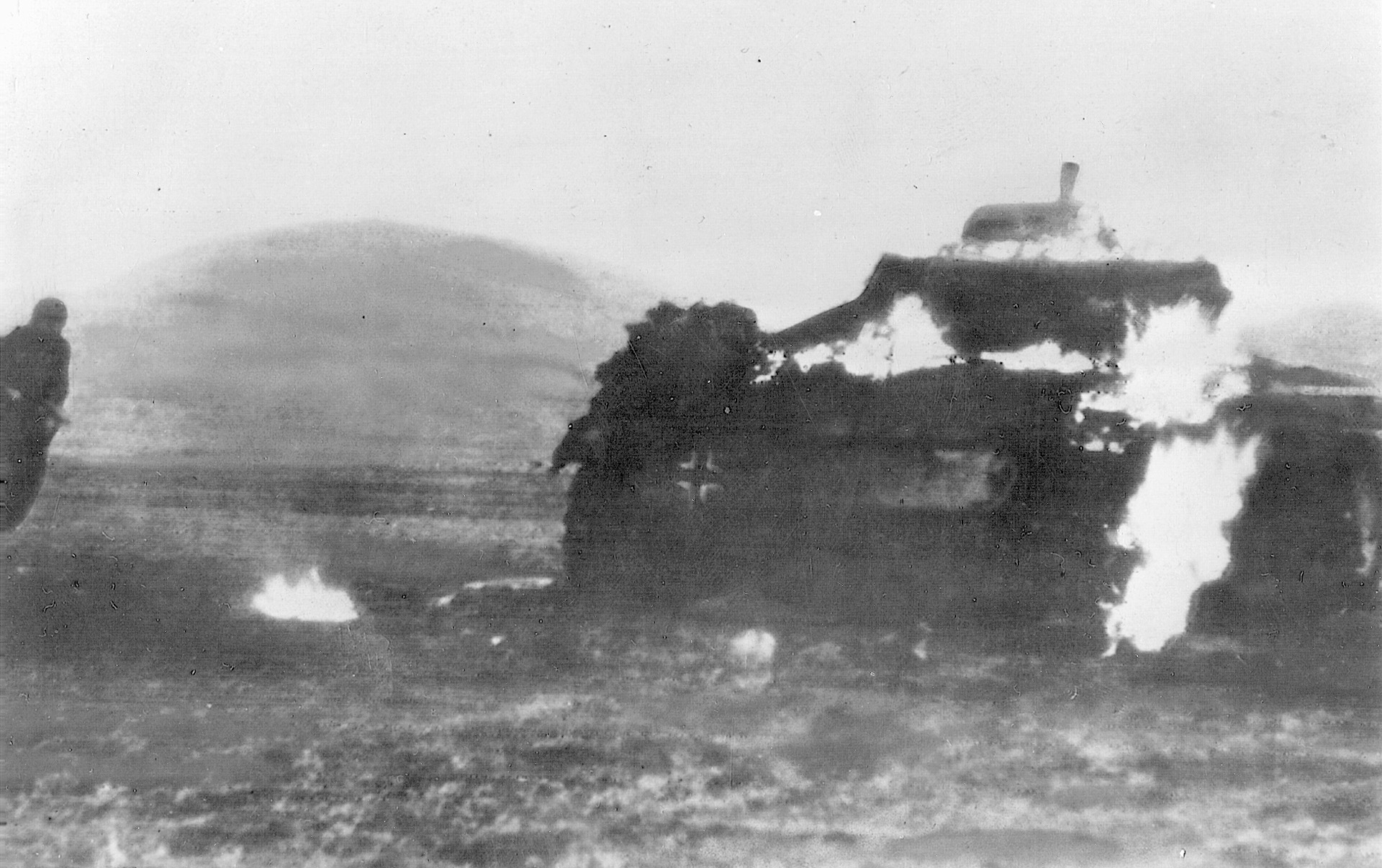

The Transportation Plan vs the Oil Plan

By the fall of 1943, the tide of war was turning against the Germans. North Africa had been cleared of German and Italian forces, Sicily had been taken after a month of hard fighting, Italy had dropped out of the war but was nevertheless invaded, and the Soviets were slowly regaining ground that had been lost to Hitler’s legions in 1941. The invasion of the Continent by the Western Allies was imminent.

Shortly after arriving in London on January 15, 1944, and assuming his duties as Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted that he take overall command of both the British and American air forces so that their efforts would be coordinated with the needs of the troops on the ground.

As Ike put it, “My insistence upon commanding these air forces at that time was … influenced by the lesson so conclusively demonstrated at Salerno [Italy]; when a battle needs the last ounce of available force, the commander must not be in the position of depending upon request and negotiation to get it.”

Ike also understood the necessity of “softening up” targets on the ground, including the road and rail networks that the Germans would undoubtedly try to use to rush reserves and tanks to the invasion sites and throw the invasion back into the sea.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur W. Tedder agreed; he had envisioned what became known as the “Transportation Plan”—using the Allies’ air assets to bomb French roads, bridges, rail lines, and marshaling yards—anything to slow the movement of German personnel, weapons, ammunition, and other vital supplies to the invasion areas.

In early 1944, Professor Solly Zuckermann, an adviser to the Air Ministry, expressed his support for Tedder’s

Transportation Plan, and Eisenhower endorsed it.

Not everyone was on board, however. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris and his RAF Bomber Command were concentrating on destroying German cities (Operation Pointblank) while his American counterpart, General Spaatz, was focused on the “Oil Plan”—the effort to knock out refineries that provided fuel for German trucks, tanks, and aircraft.

At a contentious meeting on March 25, 1944, Harris said he didn’t think his massed bombers could effectively destroy bridges and rail centers; Spaatz felt the same, despite having bragged earlier about the “pinpoint accuracy” of American “precision daylight bombing.”

Spaatz was also deeply concerned about a backlash against his Eighth Air Force in the event of heavy French civilian casualties. He said to his staff, “I won’t do it! I won’t take the responsibility. This (expletive deleted) invasion can’t succeed, and I don’t want any part of the blame.”

Ike was so angry at the reluctance of his air commanders to support the plan that he deemed vital to the success of the invasion, he threatened to resign as head of SHAEF. Eventually cooler heads prevailed, and Harris and Spaatz agreed to go along with the Transportation Plan.

One potential sticking point was the matter of likely French civilian casualties. Harris and Spaatz both told Churchill that the death toll could conceivably climb as high as 80,000 civilians and cause a negative reaction from the French against the Allies and the invasion. The prime minister wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt and expressed his misgivings about “this slaughter … among a friendly people who have committed no crimes against us.”

Roosevelt, too, was concerned but told Churchill, “However regrettable the loss of civilian life is, I am not prepared to impose from this distance any restrictions on military action by the responsible commanders that, in their opinion, might mitigate against ‘Overlord’ or cause additional loss of life to our Allied forces of invasion.”

With the “blessing” from the men at the top, the Transportation Plan was approved, and in March 1944 Ike and the rest of the planners at SHAEF pegged the end of May as the start of Operation Overlord, depending on several factors, including and especially the weather. Ike also directed the RAF and the USAAF to begin intensely striking at a long list of targets in France such as the major transportation centers at Noisy-le-Sec, Tergnier, Juvisy, and Rouen, with the intention of making roads, bridges, and railroads unusable for the Germans.

“The Flames Digested the Old Wooden Houses”

The RAF’s Rouen raid on the night of April 18-19, 1944, was especially destructive. The attack began with 16 twin-engine RAF DeHavilland Mosquito bombers from No. 514 Squadron marking the Sotteville rail yards with incendiaries. The Mosquitos were followed by 273 Avro Lancaster bombers flying at 10,000-15,000 feet and carrying 1,524 tons of bombs.

The center of the rail yard was accurately plastered by the first salvo of bombs, but the second missed badly, exploding in residential areas of Sotteville and even in the center of Rouen. The magnificent Notre-Dame Cathedral, a couple of miles from the Sotteville marshaling yards, was hit by nine bombs and suffered extensive damage to its south side, blowing out two stained-glass “rose” windows and seriously weakening the church’s 500-foot-tall, cast-iron St.-Romain spire that had once made the building the tallest in the world.

A few blocks from the cathedral, more bombs fell on the Palace of Justice, France’s largest Gothic-style civic building, and started a fire that gutted the interior. With the water mains ruptured, the firemen could do little but watch helplessly.

Residential buildings also succumbed. As one historian wrote, “The flames digested the old wooden houses,” and some 900 civilians in Rouen and Sotteville lost their lives that night. In the latter town, more than 2,200 buildings were destroyed.

After-action reports from RAF crews reported, “Weather was good with a small amount of haze. PFF markers [target indicators] were somewhat scattered. Fires and smoke from the marshaling yards were seen by some crews. There was very little opposition over the target…. Another success for Bomber Command with widespread damage to the railway infrastructure, with no aircraft lost.”

It is not known exactly how much damage was inflicted upon German interests in Rouen and Sotteville, but the bombings were badly damaging French civilian morale. After all, it was the Allies, soon to launch an invasion to free France from German occupation, who were the ones causing the awful death and destruction in one of the most treasured and historic cities in all of France.

Even though the American and British press had minimized the effects of the bombing on the populace and the infrastructure, Eisenhower was receiving reports that said the Rouennaisse were becoming incensed at the wanton destruction. But as terrible as the devastation of Rouen on April 18-19 was, worse was to come.

The Ninth Air Force Terrorizes the Railways

After the April 18-19 raid, the bombing of France was stepped up. On May 8, 1944, Marvin Schulze, a B-26 pilot with the 599th Bomb Squadron, 397th Bomb Group, wrote in his diary that Mission Number Five was “the hottest one yet. Our target was a couple of bridges near Rouen, France. We got 28 flak holes, a busted hydraulic line, a hole in oil tank. One piece came pretty close to [turret gunner] Piwitz. All ships returned.”

The official U.S. Air Force history notes, “During the first half of 1944, while the Eighth Air Force participated in the combined bomber offensive, the Ninth Air Force—commanded by Maj. Gen. Lewis Brereton and comprising the IX Fighter Command, the IX Bomber Command, and the IX Troop Carrier Command—… also carried out medium-bomber attacks on the German rocket-launching sites on the northern coast of France and, in support of the combined bomber offensive, bombed airfields and marshaling yards, primarily in France….

“By the end of April [1944], the Allied air forces had done enormous damage to many continental rail centers. The Germans responded by intensifying repair work and increasing their antiaircraft defenses around critical areas. In May, the Allied attacks expanded, but the Germans were still able to move trains.”

On May 20, responding to this continued movement, the Allies ordered wide-scale fighter sweeps against moving trains. The history continues, “Prior to this order, Allied fighters had been attacking moving trains without the express approval of higher headquarters. After May 20, the attacks were carried out openly on a large scale. In the next two weeks, fighters damaged approximately 475 locomotives and cut railway lines at more than 100 different points.

“These raids severely disrupted enemy traffic, ruined equipment, and produced important psychological effects among railroad personnel. French crews abandoned their trains in large numbers, especially after Allied fighters began dropping belly fuel tanks and setting trains on fire by strafing. The Germans reacted by manning the trains with their own crews, but that was not enough. By the end of May, the enemy had been forced to sharply curtail daylight railway operations, even where the lines remained unbroken.”

Red Week

The end of May 1944, a few days before the greatest combined air and sea operation of all time took place, is bitterly remembered in Rouen as la Semaine Rouge—“Red Week”—connoting the flames and blood that overwhelmed the city. It was during those days that the city suffered some of its most trying times.

The official history of the Royal Air Force says, “The main programme of bridge destruction was begun on 24th May by the United States Ninth Air Force, whose low-level fighter-bombers were particularly successful. By D-Day, 18 of the 24 bridges between Rouen and Paris were completely broken and the remainder blocked.”

During Red Week, hundreds of tons of American bombs fell on Rouen, killing perhaps as many as 1,500 people, obliterating more of the city’s most historic structures, completely destroying a large part of the left bank, and leaving Rouen with over 40,000 homeless.

Emmanual Delaville, a resident of the area, recalled, “During this week, about 400 tons of bombs were dropped on the area. My father, his mother, and sister were forced to live during this week in caves carved into the cliffs along the Seine River.

“Several times before my father died, he told me about the times before the war when he often went with his father to visit people who lived in … Sotteville-les-Rouen. The ward where they lived was razed by bombing in 1944 during a week known as ‘la Semaine Rouge.’”

Another observer noted, “On 30 May 1944, the city was heavily bombed. The [Notre Dame] cathedral again (in 1940 it had already suffered fire damage) fell prey to the flames and architectural damage was considerable. The inhabitants tried throughout the night to extinguish the fire.”

Devastating Attacks Leading Up to D-Day

Flying these missions could also be hazardous for the bomber crews. On May 31, 1944, the 394th Bomb Group (Medium), flying 36 Marauders from RAF Boreham, was on a mission to take out a bridge in Rouen.

One of the Marauders was piloted by Lieutenant John Connelly of the 587th Bomb Squadron. His plane was heavily weighted with fuel and two 2,000-pound bombs, and during takeoff Connelly lost one of his two engines. Making a split-second decision, Connelly chose not to jettison his bomb load, but his Marauder crashed in an orchard near the Boreham runway. The entire six-man crew survived but suffered injuries.

Most of the rest of the Marauders made it to their target and dropped their bombs, starting a fire in Rouen that spread to the cathedral’s 500-foot-tall St.-Romain tower and melted the bells.

During Red Week, Brereton’s Ninth U.S. Air Force mounted attack after attack on Rouen. At 11 am on May 30, 38 B-26 Marauders struck the Viaduc d’Eauplet, an already damaged railroad bridge that connected Sotteville with Rouen, with 142,000 pounds of bombs. At 11:15, a second wave of 35 more B-26s hit the bridge again, this time with 70,000 pounds of bombs. Finally, at 11:30, a third flight of B-26 bombers arrived. But, with dust and smoke covering the target area, the bombardiers were unable to pick out the two other bridges they were supposed to hit and jettisoned their explosives into residential and commercial areas along the river’s edge.

When, at last, the all clear was sounded, the shaken residents emerged from their shelters to inspect the extent of the devastation. Along the Seine, a bomb had penetrated a shelter beneath a bank and more than a dozen people inside were killed. Vieux-Marché, the old marketplace (and the spot where Joan of Arc had been burned at the stake), was blown apart. The ornate Palais des Consuls, built in 1734, was a shattered ruin. Much of the area near the bridges was in flames. As one historian noted, “More than 40 fire units from Rouen and the suburbs spent the afternoon and evening fighting fires and trying to save the city.”

This was not the end of Rouen’s agony. Shortly after noon on May 31, 41 more B-26s appeared and sent 68 tons of bombs hurtling down toward the temporary bridges. But the bombardiers’ aim was off and the bombs scattered across the city, destroying the L’Eden Cinéma, obliterating the 16th-century Saint Vincente church, reputed to have the finest stained-glass windows in all of Rouen, and leaving hundreds of people dead.

On the afternoon of June 1, heat from surrounding fires evidently detonated an unexploded bomb near the Notre-Dame Cathedral, setting the roof alight. The flames threatened to destroy the entire structure; it took all the efforts of the firefighters, civilians, and even German soldiers to finally extinguish the blaze.

The next evening the bridges over the Seine again came under attack, this time by P-51 Mustang fighters carrying 500-pound bombs. A temporary railway bridge was damaged, and a great number of other buildings that had managed thus far to escape destruction were lost, including the Gare d’Orleans, south of the destroyed Pont Boieldieu.

Attacks continued for another three days, damaging or destroying many priceless structures such as the 16th-century Gothic Eglise Saint-Maclou, the main post office, and the shopping district known as the Boulevard des Belges. On June 4, P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers hit the bridges that German engineers had rebuilt and what was left of the city with 83 1,000-pound bombs. The official death toll for Red Week has never been conclusively established; some accounts have as many as 1,500 residents perishing.

The Success of the Transportation Plan

The Allies invaded Normandy on June 6, 1944, and began a long, slow push across the Channel coast and into the interior of France, driving the German Seventh Army eastward as they progressed.

Despite the devastating consequences to the civilian population, the Transportation Plan worked remarkably well for the Allies in disrupting German efforts to counter the invasion. A German Air Ministry report of June 13, 1944, admitted, “The raids … have caused the breakdown of all main lines; the coast defenses have been cut off from the supply bases in the interior … producing a situation which threatens to have serious consequences.”

The report continued, saying that although “transportation of essential supplies for the civilian population has been completely disrupted … large scale strategic movement of German troops by rail is practically impossible at the present time and must remain so while attacks are maintained at their present intensity.”

As German forces fled eastward to escape being annihilated in Normandy, endless columns of trucks and tanks, many of them covered with tree branches to camouflage them from Allied air, rolled through Rouen.

One slightly wounded German soldier by the name of Franz Gockel was confronted by French civilians as he fled from the front and reached a bombed-out town. “I expected them to tear me apart,” he said. “One man pulled out a dagger, but he pointed it to the sky. ‘This is for the Americans,’ he told me.”

The Liberation of Rouen

There was no letup in the bombings; nearly every city within 100 miles of the Channel coast was hit. On June 22, 1944, Rouen was again struck from the air by the 749th Bomb Squadron, 457th Bomb Group. On August 13, the 414th Squadron, 97th Bomb Group, hit Rouen again. By this time, of course, Rouen was little more than charred rubble.

Emmanual Delaville said that his father told him about “the USAAF/RAF bombardment of Von Kluge’s army on August 25, 1944, on the south side of the Seine River in Rouen, known in France as la rive gauche.”

It was the Canadian II Corps that first reached Rouen on the ground. The official history of the Canadian Army says, “In the neck of the great bend of the Seine, at the top of which stands the city of Rouen, is a thick, eight-mile range of woodland known as the Forét de la Londe. On 27 August, the 2nd Canadian Division began the task of clearing this obstacle. First reports indicated that it was not strongly held, but shortly very serious difficulties began to appear.”

SS troops in the Forêt de la Londe, described as “definitely a suicide force,” were rushed into position in the eastern end of the forest, across the isthmus closing the river loop. The Canadian history says, “The woods, honeycombed with enemy machine-gun positions, presented innumerable opportunities for ambush, and our infantry, fighting their way through the thick bush, repeatedly found themselves being fired upon from these prepared positions by an enemy who had every avenue of approach registered but who was himself quite invisible.

“He was well supported by artillery with excellent observation, and he had many mortars. Of the fighting on 28 August, the Commanding Officer of the Calgary Highlanders said: ‘There was not a ten-yard area in the battalion position that was not hit in the course of the day;’ and his was not one of the forward battalions.”

The Germans were putting up stiff resistance to enable as many of their units as possible to cross the Seine and withdraw to the east. As the bridges had all been destroyed, the river crossings were accomplished by ferries.

The official report continues: “Both the 4th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades suffered very heavily in these operations. The South Saskatchewan Regiment led the 6th Brigade into the forest. This unit, and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada in rear of it, bore the brunt of this difficult business. The South Saskatchewan came under particularly heavy fire from machine-guns and mortars.

“After being hammered in this manner for more than 24 hours without being able to make any progress, the Battalion’s rifle companies were reduced to a total strength of about 65 all ranks. The enemy positions in the forest were not cleared until the night of the 29th-30th. Only on the morning of the 30th was the process of mopping-up south of the Seine completed. On this same day, patrols of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade entered Rouen and reported the city clear.”

After Canadian troops liberated Rouen, Emmanual Delaville said, “My father went to Rouen and he told me he will never forget the smell of death that lingered in the air.”

On August 31, 1944, the Ottawa Citizen proclaimed, “Canadian infantry from Ontario and the Maritimes entered historic Rouen today in drizzling rain, and the city reacted like a little Paris [which had been liberated six days earlier]. French Maquis [resistance fighters] were all over the city, guiding the Canadians through the streets of this ancient Seine port. Civilians poured into the streets in hundreds, waving the Canadians on and tricolors were thrust from every window as street after street was cleared of light German opposition.”

The newspaper failed to report that when the Canadian Army marched into Rouen, all the soldiers found was a giant pile of bricks, timber, roof tiles, and thousands of stunned residents picking through the wreckage of their once beautiful city.

The High Cost of Liberation

Of course, Rouen was not the only French victim of Allied bombs, nor was it even the worst. Some 1,570 French cities and towns were bombed or hit by artillery fire by Anglo-American forces between June 1940 and May 1945. As an example of the devastation, it is estimated that 95 percent of Saint-Lô was destroyed; Carentan and Caen, too, were virtually flattened. Some figures show that 432,000 homes and apartments across France were destroyed and another 890,000 homes were damaged.

The number of French civilians killed and injured before, during, and after their liberation has long been a matter of heated debate in France. One French historian estimates that more than 50,000 men, women, and children died. During 1943 alone, some 7,458 French civilians were killed by the Allied bombing of France. The total number of dead could be as high as 70,000; more than 100,000 were wounded. The French certainly paid a high price for their liberation.

Perhaps the high cost of liberation explains why so many Americans and Britons have claimed that some French people have been “rude” and “ungrateful” toward them since the end of World War II.

In June 1994, the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings, there was still palatable anger, frustration, and bitterness expressed by many of those who remembered the civilian deaths. One woman, Frederique Legrand, an infant when Allied bombers missed a bridge at Caen but killed her parents, said, “We were forgotten, left to our own devices.”

Thousands died as Caen was leveled and orphanages were too crowded to take in all the children who had lost their parents; Legrand said she became a ward of the state until she was 21. “Relatives helped raise me and my sister and brother,” she said. “But we were different from other kids. No one seemed to know what Normandy suffered.”

The Remnants of Old Rouen

Visitors to Rouen today, 70 years after the war, will see little evidence of the ravages of the bombs and fires. The first hint that something is not quite right are whole sections of the city with jarringly modernistic architecture that visibly clash with the rebuilt old sections.

But, while walking around Rouen, one encounters reminders of the horrors that unjustly visited the city on so many occasions. For example, in the Gare de la Rue Verte railroad station there is a monument to nearly 200 railroad workers who lost their lives when the bombs crashed down on the Sotteville rail yards.

On a fence surrounding the Palais du Consul there are photos showing the extent of the damage to the building, and parts of the Palace of Justice still bear the deep gouges in the stonework made by the RAF attack on April 18-19, 1944.

Only the stone archway of the Tour Saint André, minus its formerly attached church, remains standing as a memorial, much like the Kaiser-Wilhelm Church in Berlin. Within the Cathedral of Notre Dame there is a display of photos that dramatically show the damage done and how close the entire cathedral came to being completely destroyed.

Near the restored Palace of Justice there is a modest square known as the Place du 19 Avril 1944, with a fountain in its center with a modernistic sculpture of a mother kissing her child and the father and an older child looking fearfully upward toward a sky full of unseen bombers.

Many Americans and Britons today are ambivalent about the tens of thousands of German civilians who died under the rain of Allied bombs, feeling perhaps that, because they were the enemy, they got what they deserved.

The indiscriminate deaths and suffering of French civilians and those of other occupied countries at the hands of the Allies, however, are generally ignored today—or at least unknown outside these countries. It is time for these unnecessary deaths to be acknowledged.

It is not that the majority of the French people are ungrateful for being liberated. Far from it. It is just that they still wonder why they had to endure so much for their freedom.

A shame, but sadly part of war. Perhaps the French could have fought better in 1940 and avoided German occupation.

Perhaps they would have preferred to remain under the German yoke. 1,500 is a shame but America didn’t start the war and how many France Jews did they allow to be sent to German camps to be gassed and turned to ashes? I am sure it was more than 1,500 and they were French citizens. Maybe if they had fought longer then 6 weeks before they surrendered It might have been better, maybe not.