While newly minted Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer was leading his Michigan cavalry brigade to glory at Gettysburg, fellow brigadier Elon Farnsworth, himself a native Wolverine, confronted a very different fate. Of the three “boy generals” promoted scant days before the battle, Farnsworth would have by far the shortest career as a brigade commander—a scant four days.

Together with Custer and Wesley Merritt, Farnsworth was jumped from captain to brigadier general in one quick step by corps commander Alfred Pleasonton, who had successfully sought the aid of Farnsworth’s uncle, former Republican congressman John F. Farnsworth, in obtaining his own promotion. Twenty-five at the time of his promotion, Farnsworth, unlike Custer and Merritt, was not a West Point graduate. Instead, having been expelled from the University of Michigan for his role in the death of a fellow classmate, he had joined the Army and served as forage master during Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston’s 1857 expedition against rebellious Mormons in Utah.

When the Civil War broke out, Farnsworth rushed back east to join the 8th Illinois Cavalry, which had been organized and led by his uncle. Rising quickly through the ranks, he took part in some 41 battles and skirmishes before joining Custer and Merritt on Pleasonton’s personal staff in the spring of 1863. With them he shared in the Union cavalry’s first true taste of glory at the Battle of Brandy Station, Virginia, that June before heading north to Gettysburg.

On the afternoon of the third day of the battle, Farnsworth and Merritt found themselves guarding the Union left flank following the Confederate disaster at Pickett’s Charge. Their divisional commander, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, had won the unflattering nickname “Kill Cavalry” for his reckless and impetuous style. Merritt, who had engaged in a fistfight with Kilpatrick while they were undergraduates at West Point, despised his vainglorious superior. Farnsworth would never get to know him that well.

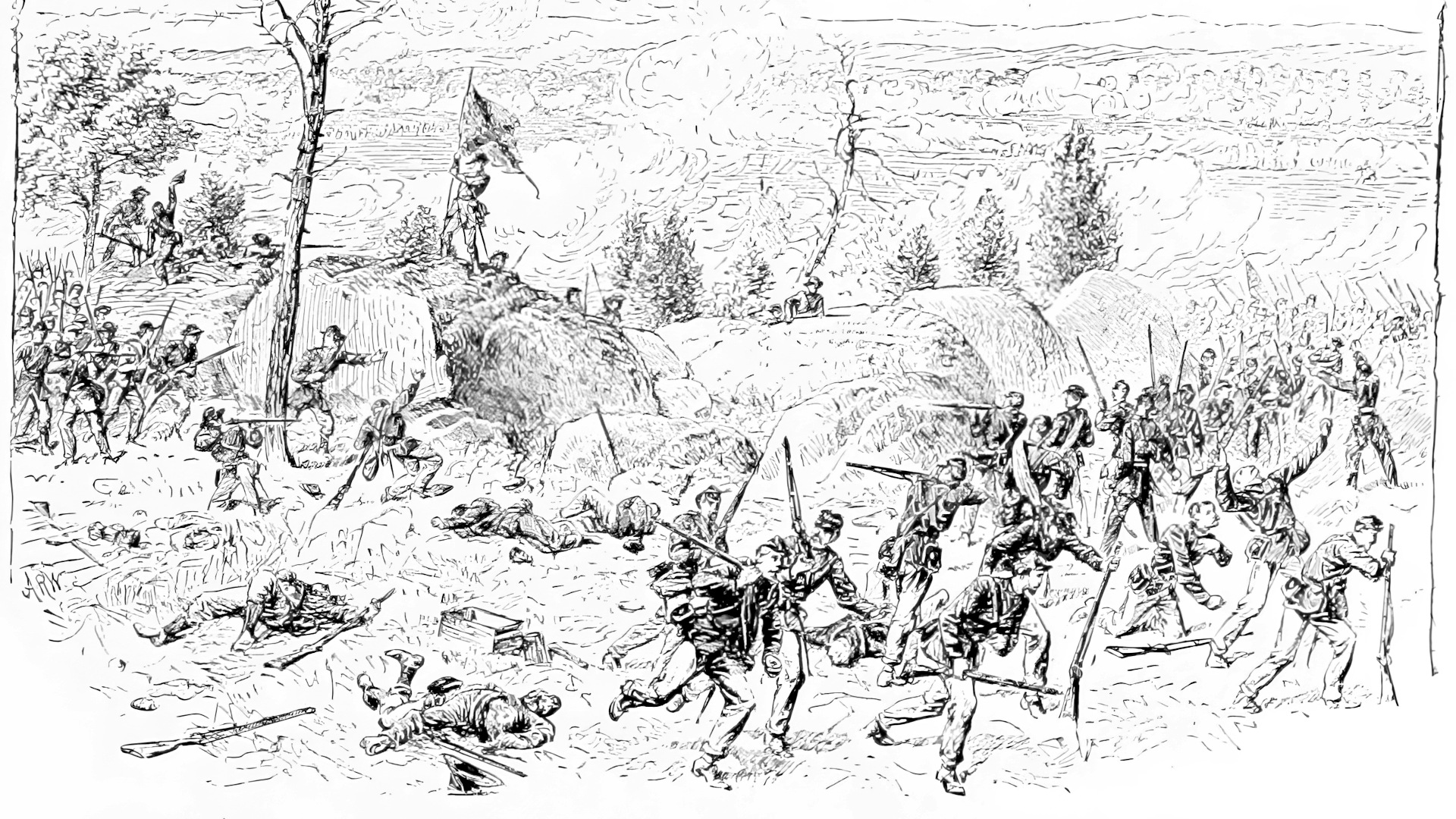

Attempting to maneuver around the retreating Confederates at Big Round Top and throw the withdrawal into total disarray, Kilpatrick turned to Merritt and Farnsworth. Merritt, sensibly dismounting his men among the large boulders and broken timber on the battlefield, made little headway. Kilpatrick turned to his other brigade commander, directing Farnsworth to break the enemy skirmish line between Big Round Top and the Emmitsburg Road.

After the 1st West Virginia Regiment failed to break the line, Kilpatrick demanded that Farnsworth commit a second regiment, the already bloodied 1st Vermont. Farnsworth could scarcely believe his ears. “General, do you mean it?” he asked. “Shall I throw my handful of men over rough ground, through timber, against a brigade of infantry. The 1st Vermont has already been fought half to pieces. These are too good men to kill.”

“Do you refuse my order?” snapped an angry Kilpatrick.” If you are afraid to lead this charge, I will lead it.” Demanding a retraction, the equally furious Farnsworth turned in the saddle. “General, if you order the charge, I will lead it,” he said, “but you must take the responsibility.”

The subsequent attack was every bit the fiasco Farnsworth had expected it to be. Confederate riflemen sheltered behind rocks, trees and fences unhorsed dozens of Union riders, including Farnsworth, who fell with no less than five mortal wounds. Called upon to surrender, the defiant Farnsworth took his own life.

Kilpatrick, having lived up to his nickname all too well, was unapologetic. The Union infantry, he said, had failed to take advantage of the mounted diversion he had obligingly provided them. As for Farnsworth, he gushed sentimentally: “We can say of him, in the language of another, ‘Good soldier, faithful friend, great heart, hail and farewell.’” Somewhere, the doomed boy general must have smirked.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments