A few short months ago, the world paused to reflect on the 75th anniversary of the end of the greatest human-caused cataclysm mankind has ever known: World War II.

By May 1945, American, British, French, and Soviet forces had left Nazi Germany lying prostrate in the dust and debris of Europe—the detritus of a war that German leader Adolf Hitler had started.

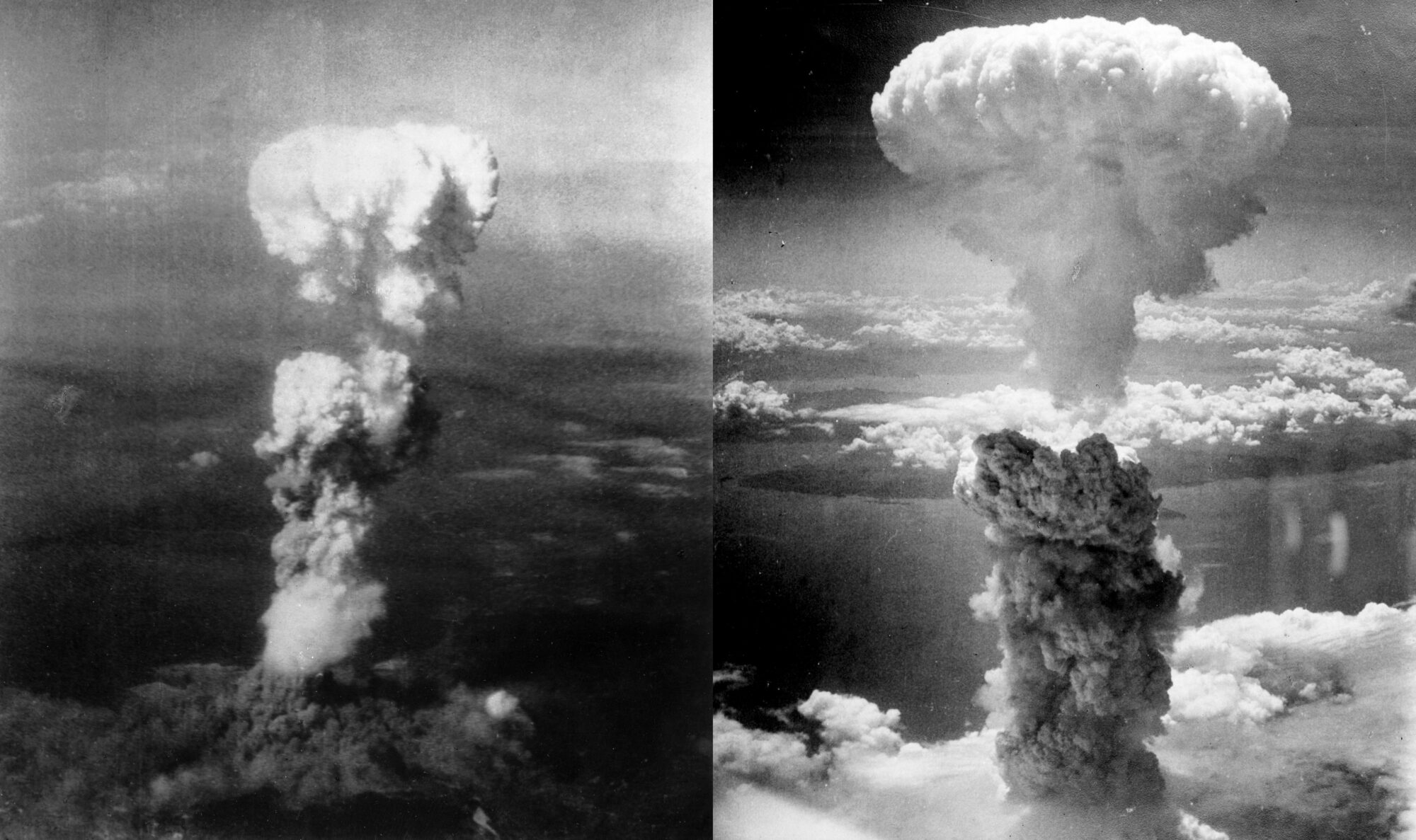

Then, on August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb, possessing a destructive force that few had ever imagined possible, obliterated the Japanese city of Hiroshima and instantly killed some 80,000 people, mostly civilians.

Reeling from what had happened and unable to quite grasp the enormity of it (as well as perhaps thinking that the explosion was a one-off event), the Japanese government failed to get the message and was punished with another bomb, this one dropped on Nagasaki three days later. Another 40,000 died in a flash.

Tens of thousands more Japanese would die agonizing deaths from burns and radiation poisoning over the next several decades.

President Harry S. Truman had inherited the bomb from his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, but the decision to employ it (or them) was Truman’s alone. What an agonizing decision that must have been.

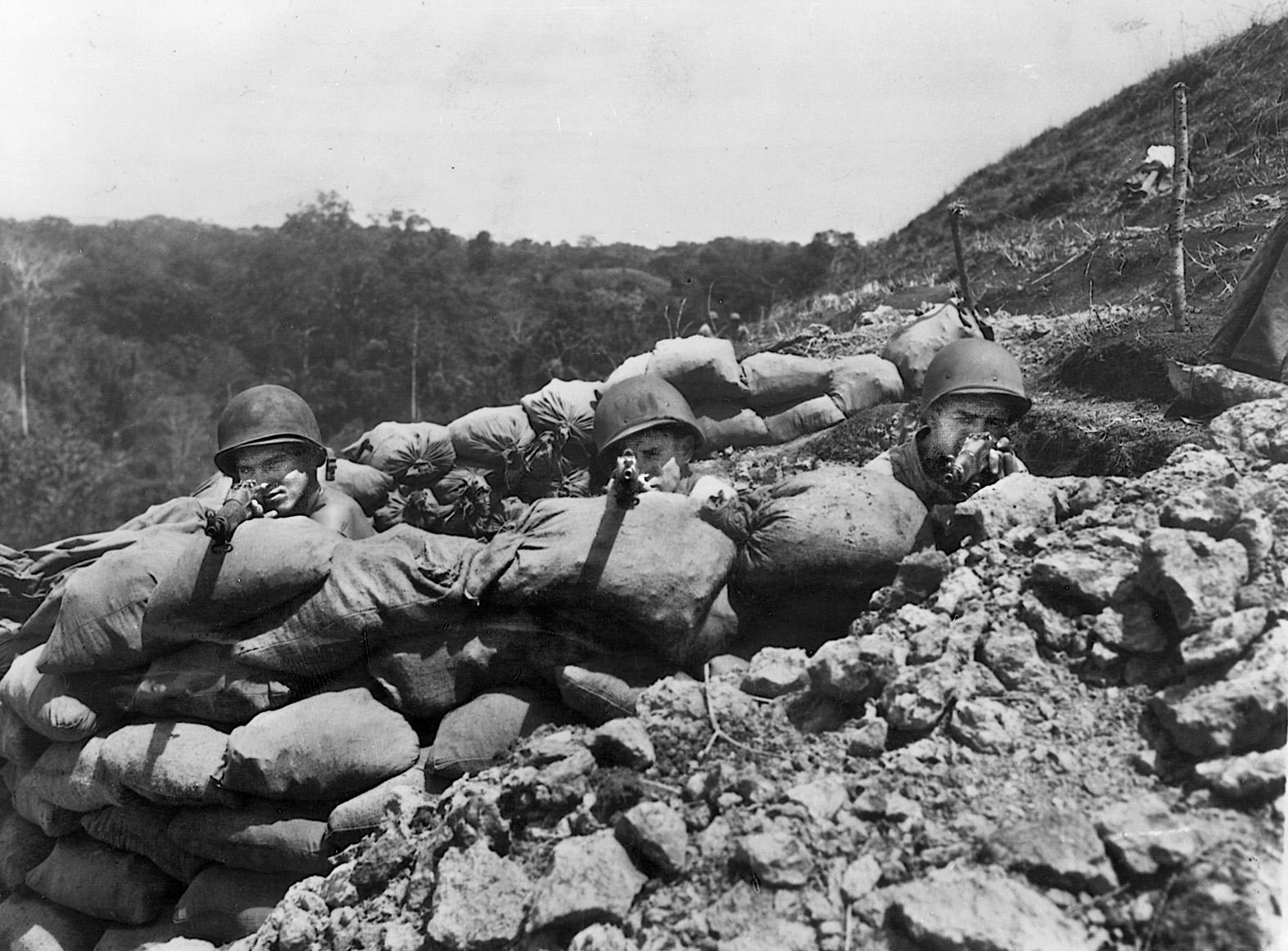

On the one hand, the bomb was almost certain to instantly snuff out human lives the way a bucket of water snuffs out a campfire. Military leaders urged Truman to use the bomb as a way of stopping the prolongation of the war and preventing another million or so casualties—American and Japanese—being added to the ghastly toll.

Had Truman not used the bomb, the howls of outrage from American families whose sons and husbands died invading Japan would have been deafening.

There was another consideration: with relations with the Soviet Union growing frosty even before the German surrender, Truman felt that it was important to let Stalin know that the U.S.—and only the U.S.—had a weapon of unimaginable power, so the Soviets had best not to get too aggressive. (Little did we know then that spies and traitors would give the secrets of the bomb to the Soviets.)

In later years, critics of Truman’s decision said that Japan was nearly defeated anyway, and that an embargo without an invasion or the use of atomic weapons would have finished her off, saving incalculable lives on both sides in the process. We’ll never know, will we?

Even some of those who helped develop the bomb had second thoughts after they saw the deaths and destruction it caused.

I remember my father, who was serving with the 10th Mountain Division in Italy when the war in Europe ended and whose unit was scheduled to take part in the invasion of Japan, telling me long after the war, “Thank God for Harry Truman and the atomic bomb.” It is a sentiment that I heard from many veterans whom I interviewed over the years.

The genie was out of the bottle, never to be stuffed back in. We live with the decision to this day.

Flint Whitlock, Editor

[email protected]