By Al Hemingway

On the cold, dark morning of January 18, 1943, the familiar sound of German Army jackboots could be heard in the Jewish sector of Nazi-occupied Poland. Since the German Army had overrun the country in 1939, more than 400,000 Jews had been herded into a cramped 1.3-mile area within the city. It was soon known as the Warsaw Ghetto. From here, the Nazi government had decided to curtail food, medicine, clothing, and other essentials to decimate the population. Once the maniacal Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and his cohorts had decided on a “final solution to the Jewish problem,” thousands of people were placed in cattle cars and taken to death camps to be gassed or put to work in slave labor camps.

But some Jews realized what was transpiring and opted to take up arms to fight their German masters. For months they collected what weapons ammunition, and food they could and constructed underground bunkers. And on that fateful winter morning they struck back—much to the surprise of the Nazis.

But some Jews realized what was transpiring and opted to take up arms to fight their German masters. For months they collected what weapons ammunition, and food they could and constructed underground bunkers. And on that fateful winter morning they struck back—much to the surprise of the Nazis.

In his new book, Isaac’s Army: A Story of Courage and Survival in Nazi-Occupied Poland (Random House, New York, 2012, 496 pp., notes, index, $30.00, hardcover), former New York Times correspondent Matthew Brzezinski has written a story of courage and hope amid the harrowing death and destruction wrought by the Nazis upon not only the Jewish people, but Poland’s Christians as well.

Brzezinski traces the creation of the various Jewish underground groups that opposed the Nazis and, at times, even fought among themselves. He follows the exploits of certain individuals who played a paramount role in the short-lived success of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The main character, Isaac Zuckerman, is described by the author as “confident and charismatic.”

Zuckerman managed to slip inside the Ghetto and organize a resistance movement to fight the Nazis. He recruited an odd but effective assortment of individuals, some no more than teenagers, to assist in his plan. Among the recruits were an 18-year-old orphan whose entire family was killed by the Nazis, Boruch Spiegel; a “quiet but resilient” person, Simha Ratheiser, who yearned for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and eventually became Zuckerman’s bodyguard; and Zuckerman’s future wife, Zivia Lubetkin, dubbed the “warrior queen” because she fought alongside her male counterparts during the uprising.

Zuckerman soon learned to his dismay that bringing the various Jewish splinter resistance groups together to form a cohesive fighting unit was as big a task as fighting the Germans. Also, the Underground Polish Army, known as the Home Army, did not offer much assistance to the Jewish underground, believing that Jews would not fight and could not learn how to use a firearm. Zuckerman had to overcome numerous obstacles to show the world that with the proper arms they could do battle with their Nazi oppressors.

Isaac’s Army provides a glimpse into the terrifying world of clandestine meetings, acts of sabotage, and the day-to-day activities of a small band of Jewish fighters bent on dying with honor rather than allowing themselves to be taken to a concentration camp and certain death. Zuckerman’s army had to constantly be on guard against spies and informants who would turn them in to the dreaded SS, who were determined to eradicate the underground movement at all costs.

When the Nazis finally crushed the Ghetto Uprising in May, many in the movement managed to escape to the surrounding countryside. Some returned to the Ghetto, however, fearing capture by partisan groups, roving bands of Ukrainian soldiers, and Polish “greasers” who made their living off the bounty they collected by snaring escaped Jews. Some fought alongside Polish Home Army soldiers during the Warsaw uprising in August 1944. Once again, the fighters received little or no aid from the Allies, particularly the Soviet Red Army, and the Nazis crushed the revolt. As with the Ghetto rebellion 18 months earlier, thousands were killed or taken to the Nazi extermination camps.

Brzezinski interviewed many of the participants who were involved in the resistance groups during that period. Their incredible story is one of survival and heroism in the face of overwhelming odds. Their bravery is a testament to the heroism of those who defied death and fought for freedom—and gave their lives in the defense of their homeland.

Resolve: From the Jungles of WWII Bataan, the Epic Story of a Soldier, a Flag, and a Promise Kept by Bob Welch, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2012, 366 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Resolve: From the Jungles of WWII Bataan, the Epic Story of a Soldier, a Flag, and a Promise Kept by Bob Welch, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2012, 366 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Lieutenant Henry Clay Conner, Jr., was indeed an extraordinary man. Embodied with steel nerves, overwhelming doggedness in his purpose, and an incredible will to survive—a will that was repeatedly tested in his nearly three years of desperately attempting to elude capture by a fanatical enemy that was every bit as determined to kill him.

When U.S. forces surrendered to the Japanese in the Philippines in April 1942, Conner decided instead to make his way with a few other Americans into the wild jungles of Luzon. Shortly after his trek, he contracted dysentery and was left behind by the group. Saved by friendly Filipinos along with other Americans who had escaped the clutches of the patrolling Japanese, his health began to improve. Soon those whose illnesses were far worse than his began to die. Conner turned to verses in his Bible to bolster his courage and began to write a journal about his terrifying experiences.

Conner and a few others formed an uneasy alliance with a small tribe of Negritos, tough resilient people who knew the rugged terrain. Their uncanny marksmanship with their crudely made bows and arrows made them a formidable foe in jungle fighting. The men created the 155th Provisional Guerilla Battalion in December 1943, comprised of about 200 men, both Negritos and Philippine Scouts, and waged a guerrilla war against the Japanese until American forces invaded Luzon in January 1945. Conner became a scout when U.S. Army units trekked into the countryside to hunt down the Japanese. On one patrol, all of his anger and frustration surfaced when he mistakenly gunned down several enemy soldiers who were attempting to surrender when he thought they were reaching for a suicide grenade. The years of pent-up emotions had taken their toll.

Oregon reporter Bob Welch has penned a remarkable tale of one man’s incredible journey of survival amid the thick, uninhabitable jungles of Luzon. Connor refused to be taken prisoner and passed along his iron will to live to those with whom he came in contact. Welch writes that the Negritos and their homeland were virtually wiped out when Mount Pinatubo suddenly erupted after hundreds of years of lying dormant. The ash that spewed for miles buried the jungle where the 155th had waged its guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. Welch equates this event to a Biblical verse from the book of Genesis that Connor was quite familiar with: “For dust you are and to dust you will return.”

Voices of the Pacific: Untold Stories from the Marine Heroes of World War II by Adam Makos with Marcus Brotherton, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2013, 416 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $7.95, hardcover.

Voices of the Pacific: Untold Stories from the Marine Heroes of World War II by Adam Makos with Marcus Brotherton, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2013, 416 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $7.95, hardcover.

Adam Makos and Marcus Brotherton have written a compelling account of 20 U.S. Marines, from their initial days in boot camp and additional rigorous infantry training, through the different island campaigns each individual participated in during their time in the Pacific. The authors answer a more important question—how can men survive the near-death experiences of war, watch their friends die, and then return home and forget it all and move on with their lives? Each of these Marines did—and that is what takes this book a step above most other oral histories.

From the landings on Guadalcanal in August 1942 until the last big battle of the war that raged on the island of Okinawa, men like Sid Phillips, Chuck Tatum, Richard Greer, Jim Young, and Roy Gerlach matched wits with their fanatical enemy and lived to tell their tale.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the book is its ending. Each individual relates his own thoughts on the fighting he took part in—and his honest view of the world he helped to save 70 years ago. Even at his advanced age, Greer travels and speaks about his time in the conflict. His definition of success, he says, is “to keep serving. Gerlach is proud of his service and realizes that what he did 70 years ago was worth all the pain. “The work we did stood for something,” he says.

Phillips is sad that many Americans today have little knowledge of the earth-shattering events that took place during the 1930s and 1940s. He firmly believes that patriotism needs to be rekindled in America. Although his has been called “The Greatest Generation,” he feels that the greatest generation is yet to come.

R.V. Burgin has no regrets about his combat in the Pacific. He is extremely proud to have been a U.S. Marine. His summation speaks volumes for all those leathernecks who stormed ashore on islands that are just a distant memory today—especially the ones Burgin served with. “The men I served with were outstanding Marines,” he says. “They were great men. Maybe the best warriors the world has ever seen.”

The Drive on Moscow 1941: Operation Taifun and Germany’s First Great Crisis in World War II by Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Drive on Moscow 1941: Operation Taifun and Germany’s First Great Crisis in World War II by Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Although German advances were significant in the early stages of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941, their initial successes were soon overshadowed by many factors. Soviet resistance began to stiffen after humiliating defeats, and the capital city of Moscow, the prime objective of the German Army, set up fortified defenses. The weather also played a significant role in the Nazi juggernaut coming to a near standstill. First, incessant rains caused the earth to be transformed into a sea of mud. Then the harsh and unforgiving Russian winter created havoc on the German offensive as well.

The authors, experts on the fighting on the Eastern Front during World War II, have dug deep and provided the reader with an in-depth look at what transpired during this pivotal period in the conflict. Despite their setbacks, German forces almost pulled off the impossible and seized the Soviet capital. If that had occurred and the Soviet Union had collapsed, the war may have had a different outcome.

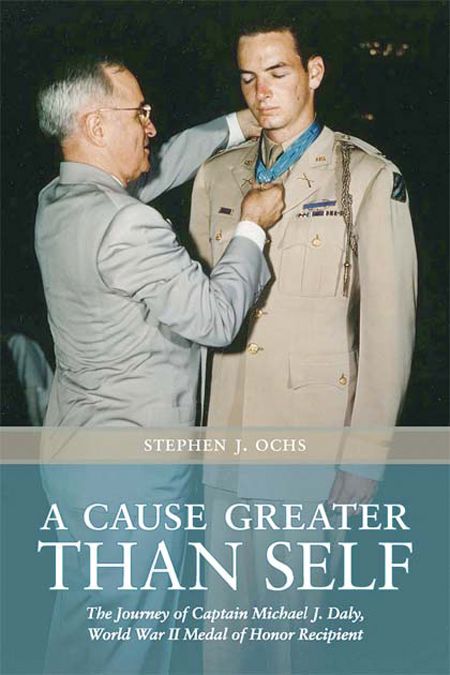

A Cause Greater Than Self: The Journey of Captain Michael J. Daly, World War II Medal of Honor Recipient by Stephen J. Ochs, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2012, 296 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $42.50, hardcover.

A Cause Greater Than Self: The Journey of Captain Michael J. Daly, World War II Medal of Honor Recipient by Stephen J. Ochs, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2012, 296 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $42.50, hardcover.

Growing up, Michael Daly was a brawler. A tough Irish kid from New York City, he learned to take care of himself at an early age. His father was a decorated World War I veteran having served with the 1st Infantry Division and wanted his son to graduate from West Point. Daly did attend the academy, but because of disciplinary problems and his being a “mediocre student,” he resigned and was soon shipped overseas in time to participate in the D-Day invasion with his father’s old unit, Co. I, 3rd Battalion, 18th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division. Surviving the carnage of Omaha Beach, Daly went on to distinguish himself in combat, was given a battlefield commission, and was sent to the 15th Infantry, 3rd Division.

On April 18, 1945, in Nuremberg, Germany, Daly singlehandedly killed 15 German soldiers and destroyed three machine-gun nests. For his bravery, he received the Medal of Honor to accompany the three Silver Stars, a Bronze Star, and three Purple Hearts he had already earned.

Daly’s story does not end there. The author writes about his inability to readjust after the war, resuming in his old antics by getting in bar fights. He finally turned his life around, got a job, and then started his own company. He went on to serve on the board of directors of the St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and was instrumental in raising funds for the facility.

This is a truly inspirational story of one man’s fight not to be locked in a “hero’s cage” and find his way through life by ridding himself of the demons that he carried when one war ended and another one began.

Sunk in Kula Gulf: The Final Voyage of the USS Helena and the Incredible Story of Her Survivors in World War II by John J. Domagalski, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2012, 239 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Sunk in Kula Gulf: The Final Voyage of the USS Helena and the Incredible Story of Her Survivors in World War II by John J. Domagalski, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2012, 239 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Here is the amazing story of the USS Helena, a light cruiser sunk at the Battle of Kula Gulf in July 1943 near the Solomon Islands. Of the crew, nearly 200 met a watery death, but many were rescued, including one group who had managed to make their way aboard a makeshift raft to the island of Vella LaVella, still in Japanese hands.

Bad luck had followed the ship ever since the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor when she was struck by a lone torpedo from a Japanese plane that killed 20 of her crew. She narrowly missed getting struck again by enemy torpedoes and planes during another battle. Because she had expended all of her flashless powder during the bombardment at Kula Gulf, she was forced to use regular powder, which made her a tempting target for Japanese submarines. A torpedo slammed into her side, quickly followed by two more, causing her to take on water rapidly.

Most of the crew managed to make it to safety. The 165 sailors who washed ashore on Vella LaVella were cared for by local natives and Australian coastwatchers who radioed in their position. A rescue force of destroyers arrived about a week later for the stranded seamen.

The author has done a superlative job in mixing official accounts with the personal stories of the survivors he has interviewed. This is a thrilling book about a group of sailors who beat the odds and survived a horrific ordeal.

Short Bursts

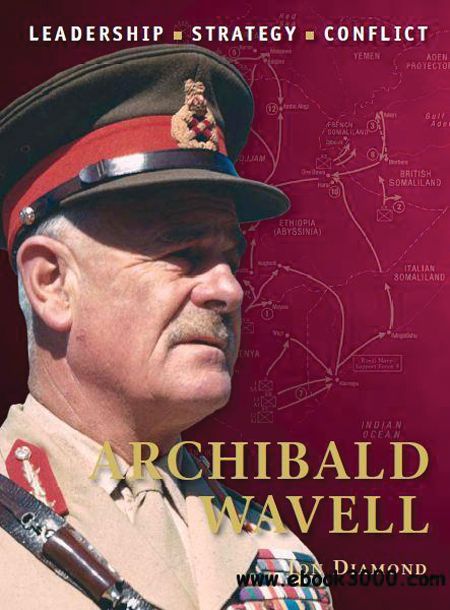

Archibald Wavell by Jon Diamond, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

Archibald Wavell by Jon Diamond, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

A soldier’s soldier, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell never forgot his roots. As a young officer in the British Army, he spent his formative years serving in the Black Watch Regiment. During World War I at the Battle of Second Ypres, a fragment of shrapnel from a German artillery piece took out his left eye.

During the years between the wars, Wavell continued to rise in rank, and when World War II broke out in 1939 Wavell’s Middle East Command encompassed nine countries and parts of two continents, certainly a massive amount of territory to cover. Because he could not breach the German defenses at Tobruk, he was relieved by Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Wavell was sent to the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations and was promoted to field marshal in 1943. He was named Viceroy of India in 1947 and died in 1950 of complications from abdominal surgery.

The author’s text is accompanied by numerous photographs, excellent drawings, and detailed maps. It is another winner for Osprey Publishing in their Leadership, Strategy, and Conflict series.

Unflinching Zeal: The Air Battles Over France and Britain, May-October 1940 by Robin Higham, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 317 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Higham’s newest book is a continuation of his previous one, titled Two Roads to War, in which he examined the roles of the air forces of Great Britain, Germany, and France at the beginning of World War II. As he states, the Battle for Britain was not Germany’s “sort of battle.” Casualties were higher, and aircraft losses exceeded the numbers they had lost during their aerial combat over mainland Europe. When a Luftwaffe plane went down, it was lost and its crew members either perished or were captured. Although they had the edge on the Brits in leadership and strategy, sheer determination and adaptability on the part of the Royal Air Force won the day.

For readers with a keen interest in the air war over Britain and a close look at the French, German, and British air forces, this a must read.

The Men of Fox Company: History and Recollections of Company F, 291st Infantry Regiment, Seventy-Fifth Infantry Division by Edgar “Ted” Cox and Scott Adams, iUniverse, Bloomington, IN, 2012, 206 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $17.95, softcover.

The Men of Fox Company: History and Recollections of Company F, 291st Infantry Regiment, Seventy-Fifth Infantry Division by Edgar “Ted” Cox and Scott Adams, iUniverse, Bloomington, IN, 2012, 206 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $17.95, softcover.

It is a shame that many of the major publishing houses overlook the personal accounts of service personnel and their units during wartime. One such infantry outfit was the 75th Division, with the motto “Make Ready,” which participated in the Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central European campaigns in World War II. Pejoratively called the “Diaper Division” because the average age of many of its members was just 22, the unit distinguished itself throughout the conflict. The authors focus specifically on Fox Company. Cox was its executive officer and replaced the commander when he was seriously wounded at the Battle of Bulge; heremained in that position until war’s end.

This is a wonderful tribute to the soldiers of Fox Company, who trained together, forged into a cohesive unit, and played a prominent role in the bitter fighting to defeat Nazi Germany.

Courage Has No Color: The True Story of the Triple Nickles, America’s First Black Paratroopers by Tanya Lee Stone, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA, 2013, 160 pp., photographs, notes, index, $24.99, softcover.

This is a truly inspirational book about the first black soldiers to attend parachute school and become the first all-black paratroopers in the U.S. Army—the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, or the “Triple Nickles”—and the obstacles they had to overcome to be accepted into the segregated Army of World War II. Their dream came true on February 18, 1944, when 16 soldiers earned the coveted U.S. Army jump wings. Instead of going into combat, however, the unit traveled to the West Coast and became smoke jumpers, paratroopers that jump into remote regions and combat forest fires. This could prove an extremely difficult task with a raging inferno. Despite these difficulties, the 555th persevered and performed its duty magnificently.

Despite all their accomplishments, the members of the 555th were still treated as second-class citizens. It would take patience and persistence until African Americans were finally integrated into all branches of the U.S. armed forces. The original members of the 555th were a part of that beginning, something of which they should be extremely proud.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments