By Christopher Miskimon

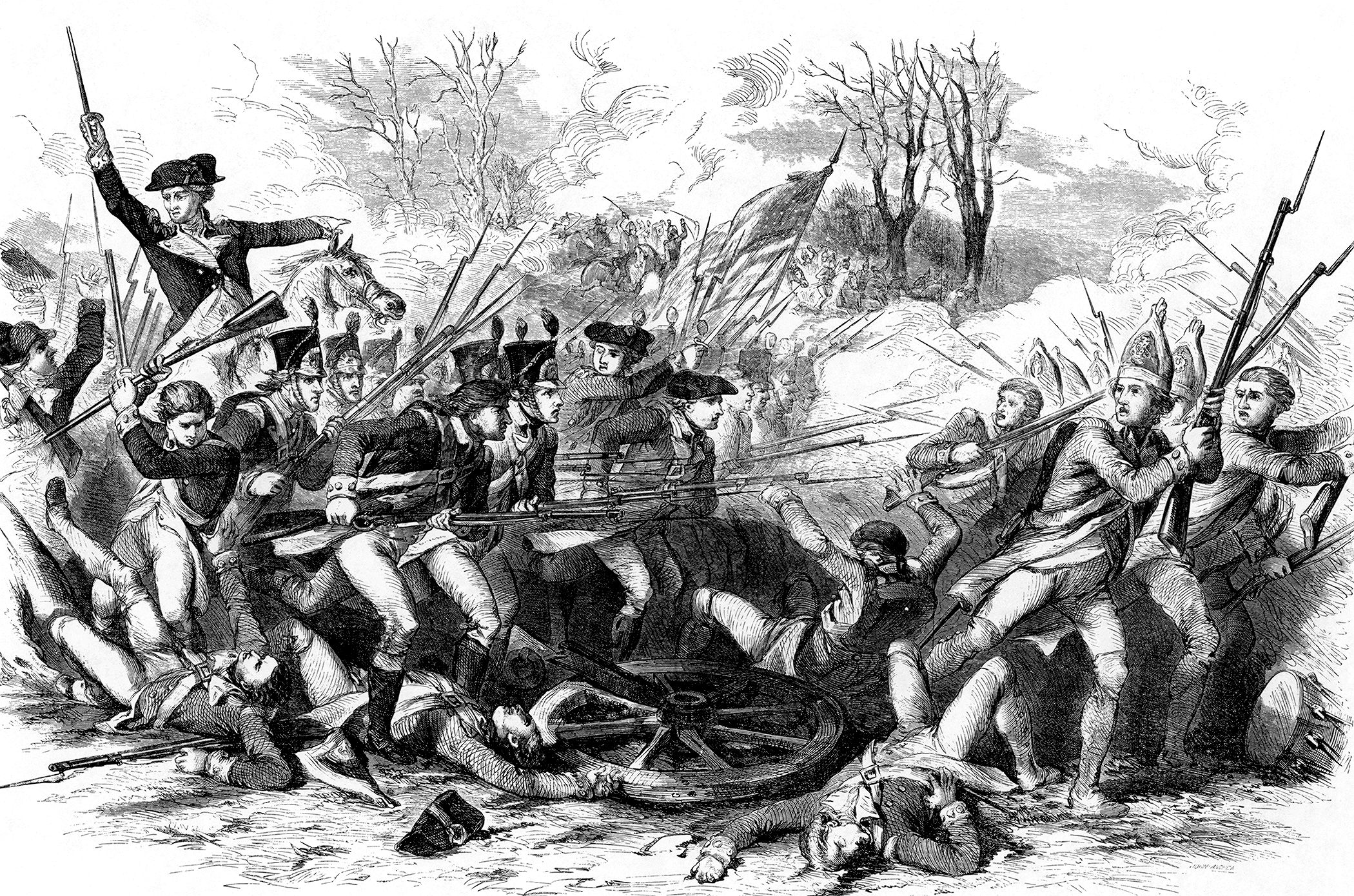

As the morning sun dawned over the village of Havre-de-Grace on May 3, 1813, a few sleepy militiamen stood watch over the Susquehanna River, watching for marauding British ships. This was the most likely approach to the small hamlet of some 50 buildings, located about 25 miles northeast of Baltimore. Only a few sentries remained; after an earlier false alarm most of the militia had been sent home. The British had been raiding towns throughout the Chesapeake Bay area for the past several weeks, but it seemed Havre-de-Grace had been bypassed.

The situation proved too good to be true. As the pickets watched, 20 barges carrying Royal Marines appeared from the south, supported by a boat laden with Congreve rockets. The few men on duty acted quickly, opening fire on the approaching flotilla with their few cannons. The sound roused the slumbering village and also sealed its fate. Towns that surrendered without resistance were generally treated better by the English, while towns that offered even a mild defense could expect to be put to the torch.

Unprepared for the attack, the town panicked. Militia officers tried to reassemble their men but many chose not to report. Civilians fled with whatever they could carry or cart off. The British opened fire on the American guns and scattered the militiamen. Only Lieutenant John O’Neill, a native Irishman, remained with two men. They fought back relentlessly until overwhelmed and captured.

Royal Marines set the town afire, aided by the incendiary effects of the Congreve rockets. One American militiaman was actually hit in the head by a rocket, a freak occurrence. Citizens watched from nearby hills as more than 150 enemy marines looted the town and set more buildings on fire. Stories circulated that the town was burned after refusing to pay a $20,000 ransom demand. More likely it was in punishment for their earlier resistance.

The wounded O’Neill was carried off to have his nationality checked. If his English captors decided he was indeed Irish-born, British law would consider him an English citizen and a traitor, subject to execution. A few days later he was released after American threats of reprisals if they executed him. It was a sad episode, proof that the War of 1812 had come to Havre-de-Grace.

The Chesapeake Bay region was a major theater of action during the War of 1812. Many readers know of its culminating events, the attack on the city of Washington and the bombardment of Fort McHenry as part of a greater operation against Baltimore. The region was also subject to numerous British raids that had great effect on the local populace. The bulk of the U.S. Army was elsewhere, leaving the defenses largely to the militia and whatever local civilian leaders could cobble together.

Like much of this war, the conduct of this campaign was a slapdash affair full of political intrigue and obtaining mixed results. The details of this struggle are well told in (Charles Neimeyer, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2015, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $44.95, hardcover).

The Canadian theater was the major concern for Great Britain. In an attempt to draw American forces away from there, the British conceived a plan to raid the Chesapeake region. It was hoped the threat this posed to major cities such as Baltimore, Washington, and Norfolk would force a redeployment of U.S. regulars away from the Canadian border. Ultimately this tactic failed; American leaders left the bay mostly to its own devices, relying on state militias and local Navy and Marine Corps forces. The militia suffered from shortcomings in discipline, training, and arms. The regular land and sea forces often had the same problems but enjoyed better leadership. All suffered at the hands of the well-drilled English sailors and marines, but when the Americans were well led and motivated they could strike blows of their own.

The book is written in clear prose that allows the reader to easily follow the story despite the numerous figures and locations. The level of detail is impressive, and both combatants’ points of view are well represented. The narrative flows through the period of the study, from the causes of the war and the Chesapeake’s part in it to the first British appearance in the bay. The numerous raids and attacks are shown with a focus on the actual participants and the entire book culminates with the disastrous Battle of Bladensburg, the burning of Washington, and the failed attack against Baltimore. The author brings well-deserved attention to a theater of war often given short coverage compared to the fighting in Canada and New Orleans. It is a fascinating and clear look at a complex time and a difficult war for the young United States of America.

Hermann Goering in the First World War: The Personal Photograph Albums of Hermann Goering (Blaine Taylor, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2015, 320 pp., photographs, appendices, $40.00, hardcover)

Hermann Goering in the First World War: The Personal Photograph Albums of Hermann Goering (Blaine Taylor, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2015, 320 pp., photographs, appendices, $40.00, hardcover)

Hermann Goering has gone down in history as one of the highest ranking members of the villainous and genocidal Nazi Party, a man given to excess who committed suicide rather than face the gallows for his crimes. He was often drug addled and unable to carry out the promises he made for his precious Luftwaffe. Today he is seen as an almost buffoonish scoundrel. Long before he made the choice to descend into infamy, Goering was just a fighter pilot, one of many fighting in the skies over Europe during World War I.

That Goering was a pilot is fairly well known, but he began the war as an infantry officer. During a period in the hospital a friend suggested he become an aerial observer-photographer. This started Goering down the aviator’s path; along the way he took many photographs, not only of battle scenes and aircraft but of the daily lives of his fellow pilots and aircrew.

The author does a good job showing a relatively unknown side of Goering without trying to glorify the man. The photographs are accompanied by text that explains Goering’s journey through the war. The book is thought-provoking; it makes the reader consider that men like Goering did not spring from the womb a full-fledged degenerate Nazi. Rather one must consider his origin and journey as a relatively normal person before later events influenced his decisions.

Their Last Full Measure: The Final Days of the Civil War (Joseph Wheelan, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2015, 407 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $26.99, hardcover)

Their Last Full Measure: The Final Days of the Civil War (Joseph Wheelan, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2015, 407 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $26.99, hardcover)

The American Civil War was spinning to a horrid finale in the first months of 1865. While the final campaigns in Virginia culminating at Appomattox come quickly to mind, climactic events were occurring across the country. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s armies were crushing the last strongpoints of the Confederacy in the Carolinas, including Fort Fischer, while other Union troops were attacking in Alabama. Combined, these three campaigns ended the rebellion. Meanwhile, other events during this time were equally important for the country. As the war ended, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, leading to the hunt for his killer.

The last five months of the war are covered in detail, each with its own chapter that breaks down the month’s major events, showing how they came together, leading to the war’s end. While it is a richly detailed history, the book reads almost like a novel. It is an engaging work that entertains as it informs.

Tanks: 100 Years of Evolution (Richard Ogorkiewicz, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2015, 344 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover)

Tanks: 100 Years of Evolution (Richard Ogorkiewicz, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2015, 344 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover)

The tank is 100 years old. The concept began as an innovation to break the deadlock of the trenches during World War I but developed over time into a mainstay of military power. That evolution moved in fits and starts; they proved themselves in the war but during the 1920s their development largely stagnated until a handful of nations began testing them during the 1930s. World War II brought the tank into its own, moving it from a support weapon for infantry to a vital part of the combined arms groups that dominated the latter part of the conflict. After the war, armor proved its continued utility as a weapon even in places people doubted they could work effectively, such as the jungles of Vietnam, or elsewhere in the Third World.

Most tank development has taken place in five countries: United States, Russia, Great Britain, France, and Germany. The work done there is covered in great detail but the author delves into what smaller nations such as Israel and Japan have done as well. Tanks are a balance of firepower, armor protection, and mobility and this book contains interesting appendices covering each, giving the reader a good understanding of what makes a tank function. The history of the tank is thoroughly investigated in great detail and clear writing. Both casual readers and armor enthusiasts will find interesting information in this book.

Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy (Frank McLynn, Da Capo Press, Boston MA, 2015, 688 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $42.50, hardcover)

Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy (Frank McLynn, Da Capo Press, Boston MA, 2015, 688 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $42.50, hardcover)

The achievements of the Mongols still have the capacity to astound. This relatively small nation of just two million people was able to conquer much of the world, creating an empire that stretched across Asia through the Middle East and into Europe, from China to Poland. Their initial influence in the 12th and 13th centuries created effects that resonate to the modern world. None of this would have been possible without the harsh and unrelenting leadership of Genghis Khan.

His world was one of complex political intrigues, raw brutality, and world-spanning warfare. Genghis possessed a sense of strategy, coupled with the talent to administer his conquests. He knew how to read men and manipulate them. The Mongol leader also had the vision and imagination to bring his dreams to reality. That reality proved cruel; thousands suffered and died often by his at times arbitrary decisions. The treachery of his rivals and followers was often imagined but he reacted swiftly and finally to any hint of it. This new biography covers the life of this infamous and important man who would today be seen as a genocidal maniac. Time has softened the results of his actions, but the author brings the man vividly to life.

Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865 (Brooks D. Simpson, Zenith Books, Minneapolis, MN, 2014, 560 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $19.99, softcover)

Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865 (Brooks D. Simpson, Zenith Books, Minneapolis, MN, 2014, 560 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $19.99, softcover)

Ulysses Grant is a complex character and this has allowed biographers to characterize him as they please. Some choose to focus on his drinking habits, his difficulties as president, or looking at his willingness to accept casualties as butchery. Others paint him as the perfect man in the right place at the right time. This biography portrays Grant as a very human figure, not perfect but eminently able to succeed as a warrior under difficult conditions.

This book concentrates on Grant’s earlier life, from his birth through the end of the American Civil War. His military career as well as his personal and family life are covered, showing the full scope of his experiences. This allows the reader to see all of what made Grant who he was and learn what helped drive him forward. In the end, he was far from perfect but certainly in the right place at the right time to take the Union armies to victory.

First Over There: The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle of World War I (Matthew J. Davenport, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 2015, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.99, hardcover)

First Over There: The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle of World War I (Matthew J. Davenport, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 2015, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.99, hardcover)

The sun was just rising behind the German trenches on the morning of May 28, 1918. As it appeared, thousands of American infantrymen rose from their trenches and pressed forward. They wound their way through barbed wire and shell holes, braving horrendous machine-gun fire to attack the German lines. After grueling close-quarters fighting they seized the village of Cantigny, atop a hill just inside the territory the Germans had taken during their 1918 offensive. For the next two days they would endure harsh counterattacks, including punishing artillery fire and choking mustard gas.

This book covers the U.S. Army’s first combat operation through the letters, diaries, and battle reports of the participants. This action brought American arms into the age of modern warfare; the battle included the use of modern artillery, the king of the battlefield, along with tanks and aircraft. Much of the planning was done by George C. Marshall, at the time a lieutenant colonel, who would go on to lasting fame in World War II. The future Army leader would learn his deadly trade through the fighting for Cantigny.

The author does an excellent job covering everything about the battle from the highest level operational planning down to the personal experiences of privates and corporals fighting in shallow foxholes and shedding their blood into the dark soil. This book brings the Battle of Cantigny to life on an engaging and lively way.

Bosworth 1485: The Battle that Transformed England (Michael Jones, Pegasus Books, New York, 2015, 288 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover)

England’s future was changed irrevocably on August 22, 1485. At the Battle of Bosworth Field, Richard III was slain. His death ended the Wars of the Roses and initiated the Tudor Dynasty, which included such pivotal figures as Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. At Bosworth Field, Henry Tudor relied largely on French mercenaries equipped with pikes. The battle ended with a fateful cavalry charge by Richard’s supporters. This may have been where Richard met his end.

The Battle of Bosworth Field was less well-chronicled at the time it occurred, but the author pulls together what is available to provide an engaging account of an important event in British and world history. He shows how the battle took place in a different location than the accepted one. He also rejects the image of Richard as timid, maintaining the monarch was energetic and aggressive in his actions. In some ways the book is a reinterpretation of the battle, but the book’s detailed research makes a good argument for the author’s assertions.

Wellington’s Rifles: The British Light Infantry and Rifle Regiments, 1758-1815 (Ray Cusick, Carrel Books/ Skyhorse Publishing, New York NY, 2015, photographs, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

Wellington’s Rifles: The British Light Infantry and Rifle Regiments, 1758-1815 (Ray Cusick, Carrel Books/ Skyhorse Publishing, New York NY, 2015, photographs, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

Before and during the Napoleonic Era, most soldiers carried smoothbore muskets of limited accuracy. Occasionally, a unit would be armed with the slower firing but more accurate rifle. Such formations were often considered elite, either as scouts or skirmishers but also as light infantry. The British Army raised a number of such regiments during the period, introducing them around the time of the French and Indian War. Over the next few decades riflemen proved themselves in combat time and again until they were considered a key part of the Royal Army. With the concept proven, rifle regiments played a key part in Wellington’s Peninsular army in Portugal and Spain. Later they would again serve ably against Napoleon at Waterloo.

The story of Britain’s light infantry troops receives well-deserved and overdue attention in this new work. How the units were organized and trained along with their innovative tactics are all covered in detail. There is also extensive coverage of how these units evolved over the decades as their performance earned acceptance by doubtful senior officers. Coverage of their significant battles completes the book, making it a thorough account.

For God and Kaiser: The Imperial Austrian Army (Richard Bassett, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2015, 592 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover)

For God and Kaiser: The Imperial Austrian Army (Richard Bassett, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2015, 592 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover)

For three centuries the army of the Imperial Hapsburg dynasty fought for Austria in its various guises. The nation itself went through several evolutions between 1600 and 1918 when Austro-Hungary finally dissolved in the aftermath of World War I. During that time the Austrian Army fought in many of the major conflicts of Europe, balanced as it was between the powerful nations of Western Europe and the often hostile states to the east, such as that of the Ottoman Turks. Often the region was a hotbed of religious warfare first as Islam sought to spread into the Continent and later as Christendom struggled to push them out. At the same time, it was really a multinational force that included Muslims in its ranks.

The Austrian Army is often portrayed as second-rate but the author makes a compelling case in defense of it. He effectively asserts the army fought effectively in numerous conflicts, often having to fight in several directions at once and wielding soldiers from various states. Its ability to shape these troops into a cohesive fighting force for so long was a major achievement seldom equaled in history. This book weaves several centuries of rich detail into a readable, easily to follow history on a subject rarely covered in English language publications.

Short Bursts

Professor Porsche’s Wars (Karl Ludvigson, Pen and Sword Publishing, 2015, $50, hardcover) A behind-the-scenes look at the famous German engineer who designed weapons for four decades. This includes everything from tanks to amphibious cars.

Professor Porsche’s Wars (Karl Ludvigson, Pen and Sword Publishing, 2015, $50, hardcover) A behind-the-scenes look at the famous German engineer who designed weapons for four decades. This includes everything from tanks to amphibious cars.

Roman Legionary AD 284-337: The Age of Diocletian and Constantine the Great (Ross Cowan, Osprey Publishing, 2015, $18.95, softcover) These two figures were the greatest of the Late Roman Emperors. Their legions were the height of their military system.

The Journals of Jeffery Amherst, 1757-1763, Volume I (Robert J. Andrews, Michigan State University Press, 2014, $124.95, hardcover) Amherst was the commander of British Forces in North America during the Seven Years War. This volume contains his daily and personal journals, giving insight into the events of the conflict.

The Journals of Jeffery Amherst, 1757-1763, Volume II (Robert J. Andrews, Michigan State University Press, 2014, $99.95, hardcover) The second volume is a dictionary of all the people, places, and ships mentioned in his journals. This allows the reader to round out his entries, providing more in-depth understanding.

Scapegoats: Thirteen Victims of Military Injustice (Michael Scott, Skyhorse Publishing, 2015, $24.99, hardcover) Failure in war usually results in blame being attached to the leaders involved. Here are case studies of 13 men who the author argues were unfairly castigated for military setbacks.

Soldiering for Freedom: How the Union Army Recruited, Trained and Deployed the U.S. Colored Troops (Bob Luke and John David Smith, John Hopkins University Press, 2015, $19.95, softcover) The use of African American former slaves in the Union Army was a controversial decision but ultimately the moral, correct one. This book shows how these men went from the recruiting station to the battlefield.

The War That Forged a Nation: Why the Civil War Still Matters (James McPherson, Oxford University Press, 2015, $27.95, hardcover) The Civil War is a pivotal event in American history. The author explains how its significance is still relevant today and why we are still realizing its implications.

The War That Forged a Nation: Why the Civil War Still Matters (James McPherson, Oxford University Press, 2015, $27.95, hardcover) The Civil War is a pivotal event in American history. The author explains how its significance is still relevant today and why we are still realizing its implications.

Enduring Freedom, Enduring Voices: US Operations in Afghanistan (Michael G. Walling, Osprey Publishing, 2014, $25.95, hardcover) This book combines accounts from commanders, Special Forces troops, and other soldiers to reveal how the war in Afghanistan was experienced by those who fought it.

A Higher Form of Killing: Six Weeks in World War I That Forever Changed the Nature of Warfare (Diana Preston, Bloomsbury Press, 2015, $28.00, hardcover) In six weeks between April and May 1915, the first use of chemical weapons occurred, zeppelins appeared, and the RMS Lusitania was torpedoed. These events changed warfare forever.

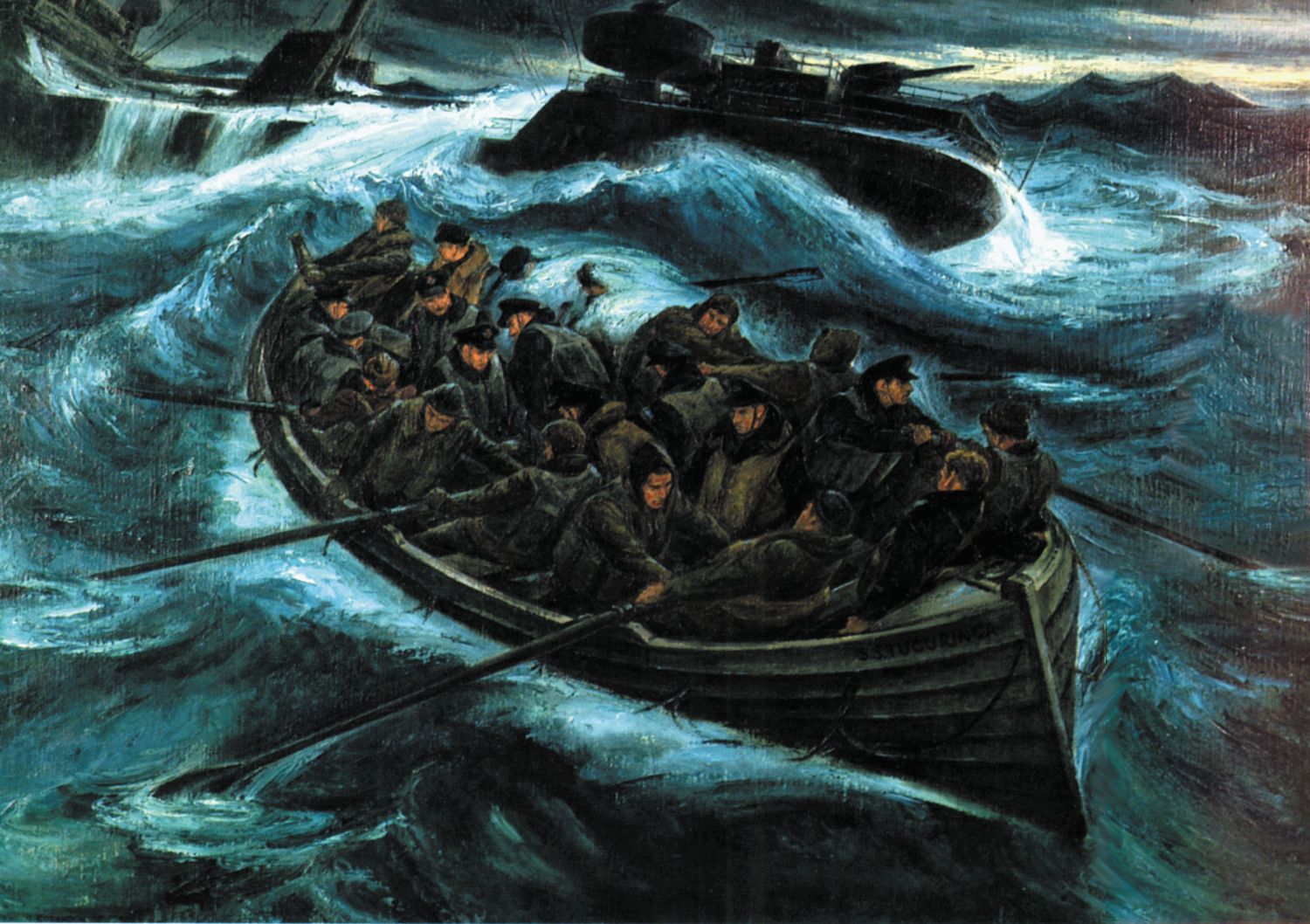

The Baltimore Sabotage Cell: German Agents, American Traitors, and the U-boat Deutschland during World War I (Dwight R. Messimer, Naval Institute Press, 2015, $35.95, hardcover) Germany tried to break the British blockade with cargo submarines and sabotage U.S. factories making arms and equipment for the United Kingdom. This is the story of the spy ring that carried out the German scheme.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments