By John W. Osborn Jr.

“We were to be terrorists. Our job was to terrorize the Germans,” one former member said dramatically. Another more prosaically likened it to poaching: “Creep in, set the traps, hang about, collect the spoils, and get away without being caught.”

Both descriptions were equally appropriate in describing one of the least known special forces units of World War II. Although British, it owed its origin, ironically, to the Germans. They had designed a collapsible sporting canoe, effective for both shallow water and deep, rougher seas, called a Folbot. A British officer, Major Roger Courtney, discovered it paddling the length of the Danube on his honeymoon, and he went on to organize a unit of the craft to raid Mediterranean ports. It caught the eye of the legendary founder of the Special Air Service, Colonel David Stirling, and he brought it into the SAS as its Folboat Section.

The Folboat Section “carried out many brilliant operations,” according to Stirling, none more so than during the run-up to Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942.

It landed General Mark Clark on an Algerian beach for his critical meeting with Vichy French officers, smuggled French General Henri Giraud out of occupied France, laid marker guides for the landings, and raided Oran Harbor. After Stirling’s capture, the SAS was broken up. The Folboat Section was established as its own independent unit, the Special Boat Squadron, later the Special Boat Service (SBS), on March 17, 1943. Its first commander was 24-year-old Lt. Col. George, 2nd Earl Jellicoe, son of the World War I Admiral John Jellicoe, who commanded the Royal Navy forces during the pivotal Battle of Jutland.

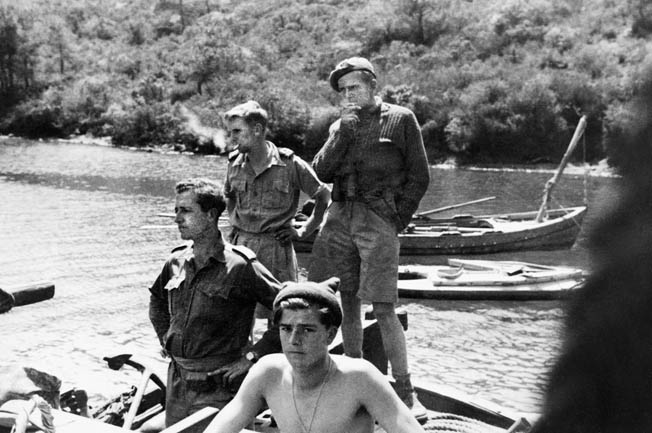

Jellicoe organized and trained the SBS at a base at Haifa, Palestine, with never more than 100 men under his command at any time. Starting with Folboats launched from submarines, the SBS moved up to caiques, Greek fishing schooners the SBS valued for their range, endurance, and the fact that there were too many of them in use for the Germans to attempt to search them all, and finally to fast motor launches.

The SBS fought its way through the Mediterranean, the Aegean, and the Adriatic, on the Dodecanese and Dalmatian Islands, in Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, and Albania. The SBS would paddle, sail, or speed from out of the darkness into an enemy harbor, either to silently attach limpet mines to shipping or loudly shoot up and blow the place apart, sometimes continuing inland to commit sabotage.

“The SAS liked to burst gallantly through the front door,” an SBS captain remarked, “while the SBS preferred to slip in at back through the bathroom window.”

Although Jellicoe commanded and its accidental founder Roger Courtney was in it, the most important figure of the SBS would in fact not be British at all. “In England,” remembered Jellicoe, “I met a marvelous Dane named Andy Lassen.”

his fighting knife prior to a mission.

Lassen was a 20-year-old cadet-officer aboard a British merchant ship in the Persian Gulf the day he heard of the early morning German blitzkrieg against Denmark, leading a veritable mutiny to reach the nearest port. From there he headed straight to England to join what there was of a free Danish army. Too impatient for regular soldiering, he joined the Special Operations Executive.

By the time Jellicoe acquired Lassen for the SBS, he had already earned the first of eventually three Military Crosses. But their association almost ended before it could get properly started—in a bar back in Palestine. “I must have said something that offended him and ignited his quick fuse,” remembered Jellicoe. “Two or three minutes later I found myself getting up from the floor.”

Jellicoe would have been in his rights seeing Lassen in the stockade for the rest of the war; instead he had him spend it in the thick of the deadliest, most desperate SBS operations of the conflict. “He was brave with such a calm, deadly, almost horrifying courage,” another officer said, “born of a berserk hatred of the Germans who had overrun his country. He was a killer, too, cold and ruthless—silently with a knife or point-blank range with a pistol. On such occasions, there was a froth of bubbles round his lips, and his eyes were dead as stones.”

The last operation for the SBS in World War II was against a network of German pillboxes and machine-gun posts in Italy after midnight on April 9, 1945, led, aggressively from the front as always, by Anders Lassen.

The heroic Dane’s sergeant major, Leslie Stephenson, had his doubts: “All our success had come from stealth, but now we were used for an infantry assault that, considering our type of soldiering, was a suicide mission.”

But Lassen evidently did not care. He had impatiently, angrily, been kept from action for months, but shortly before this fight had talked ominously for the first time about possibly not making it back.

Lassen was making sure the Germans did not survive the onslaught, singlehandedly knocking out two pillboxes and a machine gun with grenades. “He forgot where he was,” one of his men remembered. “He forgot about taking cover. He forgot every damn thing except going forward.”

At the next pillbox he heard a shout of “Kamerad!” and ordered Stephenson and the others to stay back as he approached it alone. He disappeared from view around the side. Then there was a burst of machine-gun fire. Seconds that seemed as long minutes to Stephenson passed. Then, “SBS, SBS, Major Lassen wounded. Here.”

Stephenson dashed to find the Germans gone and Lassen on his back. “Who is it?” the wounded man asked.

“Steve.”

“Good. Steve, I’m wounded. I am going to die.”

Stephenson put a morphine tablet on Lassen’s tongue, assuring, “We’re going to get you back.”

“No use, Steve. I’m dying and it’s been a poor show. Don’t go any further with it. Get the others out.” These were Lassen’s last words.

There was understandable bitterness inside the SBS for such a loss in what was regarded as a pointless attack with the war’s end so close. But there had already been another loss, the full extent of the tragedy not known for decades.

The half dozen men of Mission LS24 had disappeared in the Aegean in April 1944, the only SBS operation never to return. “The war is over but they remain listed as ‘missing,’” an officer sadly wrote in 1947. It was not until the 1980s that the terrible truth came out. They had been captured, tortured, and executed by the Germans.

Tragedy became international scandal over the role played in their fate by an officer named Kurt Waldheim. During his international career, culminating as secretary-general of the United Nations from 1971-1982, Waldheim’s story that he was medically discharged from the German Army in 1941 with a leg wound sustained on the Eastern Front had been accepted without scrutiny. But, while running for Austria’s ceremonial presidency in 1986, the truth came out. Waldheim had served through the entire war, including in the intelligence unit responsible for the interrogation and elimination of Mission LS24.

In the end it was established he had been on leave at the time and was too junior, as a lieutenant, to order or stop anything . But his claim that he knew nothing about it was found hard to accept. It seemed likely he would have heard of something so important later, or if he did not it was because he did not want to know, given the unit’s record of more war crimes.

In the end Kurt Waldheim could not escape the moral taint of LS24 and other war crimes. When he did win the election, Great Britain and the United States immediately withdrew their ambassadors from Vienna, sending no replacements, and Waldheim sat out his term internationally ignored.

Anders Lassen was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, but it was the only recognition that the Special Boat Service got out of the war. Fighting in such obscure corners of the conflict, it had never attracted the attention of the renowned Commandos, the Special Air Service, or the Long Range Desert Group, and the buccaneering, piratical image it enjoyed repelled the more conventionally minded, such as Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

During an astonishing exchange in Parliament in 1944, Churchill was asked, “It is true, Mr. Prime Minister, that there is a body of men out in the Aegean Islands, fighting under the Union Jack, that are nothing short of being a band of murderous, renegade cutthroats?”

Churchill found himself in the rarest of situations for him—at an utter loss for words. “If you do not sit down and keep quiet, I will send you to join them,” was all he could say in frustration.

The Special Boat Service was disbanded in September 1945, then was later reestablished in the Royal Marines. It struggled on for years, understaffed, underfunded, a career waystation, the more famous SAS mocking that its initials stood for “Shaky Boats.” The SBS finally made its new reputation in the Falklands War, including crucially locating what became the landing beach at San Carlos Bay.

Accepting just one candidate in 25, the Special Boat Service is now acknowledged as one of the toughest and most secretive units of its kind in the world. Further serving in locales like Bosnia and the Persian Gulf, it has lived up to what could have been its motto in World War II. “By Guile, Not Strength.”

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., has contributed to WWII History on numerous occasions. He writes from his home in Fort Myers, Florida.

I am waiting for the WWII pic of the young woman, a Balkan Resistance Fighter (Chetnik?) being hung by the Nazis. “You will know my name when they come to avenge my death”.

Thank you for a interesting artiklen about my fellow dane Anders Lassen.

There is a statue of Lassen at Tybjerg, Dk which is ofren visiter by the British forces when on exercise in Dk.

I have been there together with them paying our respekt in several occations during my servicewith the Danish Husars

Anker Mikkelsen