By Eric Niderost

In the spring of ad 60 Gaius Suetonius Paulinus could look back on the last three or four years with a mixture of pride and satisfaction. As governor of the Roman province of Britannia, he had seen to it that the island was pacified and generally prosperous. Under his direction the process of Romanization—the introduction of Roman civilization and culture into a newly won land—was well advanced. Roman engineers were busy building paved roads whose sturdy flagstones echoed to the creak of the merchant’s cart and legionary’s booted sandal.

Roman towns and cities were springing up everywhere. Camulodunum was Britannia’s first official city, a colonia or colony of retired Roman legionaries. It was also the capital of Roman Britannia, its status proclaimed by the fabulous Temple of the Deified Claudius, one of the finest classical structures north of the Alps. There was also Londinium (now London), a thriving commercial center on the banks of the Thames River. Londinium was a convenient river crossing, and the Thames was deep and still tidal along its shores, which made the site ideal for shipping and commerce.

Given the fact that the Romans had only invaded in ad 43, Suetonius could be justifiably proud of the things the Romans had achieved in a scant 17 years. True, there were occasional minor revolts here and there, but this was to be expected in such a relatively new province. But Suetonius was concerned with the island of Mona, just off the coast of what is now northwestern Wales. The island was a stronghold of the Celtic Druid religion and a refuge of malcontents. It was imperative that Mona be subdued and its nest of rebels exterminated. The governor was a talented man who was also ambitious. Winning fresh military laurels would further his career in Rome.

Sometime in ad 60 or 61—the sources are not precise—Suetonius led an expedition to Mona, modern Anglesey. The Legio XX Valeria (20th Legion Valeria) formed the backbone of the governor’s army, together with auxiliaries and some cavalry. The first task was to cross the straits that divided Mona from the Welsh mainland. Suetonius had flat-bottomed barges built to ferry the heavy infantry across; the cavalry managed to find a partial ford, then swam the rest of the way.

The Roman crossing was uncontested, but if the invaders thought they had achieved an element of surprise, these sanguine hopes were soon dashed. A huge number of Celtic warriors appeared at the scene, accompanied by women and Druid priests. The Roman cohorts took their battle positions, forming up under the watchful gaze of their centurions. The Romans stood in their ranks, impassively waiting for action, yet each man must have felt an involuntary shiver of fear when he beheld the barbaric spectacle that was playing out before his eyes.

Mustachioed Celtic warriors, some of them tattooed or daubed in a blue dye called woad, brandished weapons and shouted fierce imprecations. Long-robed Druid priests raised hands in unison, loudly invoking their gods with booming voices. But the women were the most frightening apparitions of all—wild-eyed furies who ran about brandishing light torches and screaming the most terrible high-pitched ululations. Their long ropes of hair and contorted faces were Medusa-like in horrific intensity.

The Roman legionaries stood transfixed, rooted to the ground in fear, half-hypnotized by the hellish vision before them. At this critical juncture Suetonius stepped forward and addressed the men, instinctively realizing that only he could exorcise their growing fears. What he said was not recorded, but most likely he reminded the legionaries they were Romans, and that they had conquered before and would do so again.

The governor’s words had the desired effect; the spell was broken. The legionaries sheepishly chided themselves for their momentary weakness and encouraged each other to new heights of valor. The eagle standards went aloft, and the cohorts moved forward. Little detail is given in historical accounts, except to say the Druids and their forces were utterly routed with great slaughter. Roman troops scoured the island, putting everything to the torch. The holy places of the Druid religion, notably the sacred groves where human sacrificial rites had been performed, were singled out for special attention.

The task was now complete, but there were some last-minute arrangements to be made, such as providing the island with a permanent garrison. Suetonius was in the midst of mopping-up details when a messenger came to him with a startling piece of intelligence—in his absence Britain had revolted. This was no mere “brushfire” affair, but a full-scale conflagration that might wrest the whole province from Roman control.

The governor’s eyes scanned the Latin words, his mind scarcely able to absorb the chilling story they told. Queen Boudicca of the Iceni tribe was leading the revolt, and her army was growing by the day. It looked as if the Trinovantes tribe was going over to Boudicca—if this was so, then the capital at Camulodunum (now Colchester) was threatened, since it was deep in Trinovantes territory.

This news was troubling, and a cause for concern, but not undue alarm. After all, there were three other legions in Britain—the XIV Gemina, II Augusta, and IX Hispana. Nevertheless, Suetonius knew only he could provide the leadership that would coordinate Roman efforts in suppressing the revolt. The governor issued orders for all units under his command to head south without delay.

The rebellion had many causes, but Roman greed and arrogance topped the list. After a territory was conquered the Romans usually made sure that firm alliances were made with the native elite. Local British kings and chieftains were given status and power within the fledgling society, but only if they and their retainers became Romanized. They had to learn Latin, adopt Roman dress and social customs, and live in Roman cities or Roman-style country villas. More importantly, their sons and daughters went to Roman schools and learned Roman ways.

Within a generation or two the British Celtic aristocracy would be Roman, not merely Romanized, and imperial power in Britain would be secure. But all that would be in the future. For the present, the average British king or chieftain found that Romanization was a costly process. Building a Roman-style villa or becoming the patron of a new Roman town required a substantial outlay of funds. Not long after the initial conquest, Emperor Claudius had given large sums of money to the most prominent British kings to begin the process

Because the British aristocrats had little choice but to borrow money, the custom opened the door to all kinds of abuses. Roman loan sharks descended on the island like a plague of rapacious locusts, forcing the natives to accept loans with ruinous rates of interest. The loan system became a kind of semi-official extortion, a lucrative game that was played by the highest officials in the imperial court. Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Emperor Nero’s tutor and a celebrated Stoic philosopher, displayed an all-too-human greed that was at variance with his Stoic principles. Seneca had advanced some 40 million sesterces in forced loans to native chiefs, and he expected a handsome profit in return.

British resentment over such high-handed treatment provided the tinder of rebellion; all that was needed was a spark to set the whole country ablaze. Decianus Catus was the provincial procurator, an official largely responsible for the smooth collection of taxes and other fiscal matters. Catus was scheming, tactless, cruel, utterly unscrupulous, and—judging by later events—a coward to boot. The Icenian revolt had many underlying causes, but if one man could be held directly responsible, it was Decianus Catus. Suetonius’s absence in far-off Wales provided Catus a literally golden opportunity to feather his nest at the expense of the natives.

The Iceni inhabited the regions around modern-day Norfolk and Suffolk, where the rounded southeastern bulge of Britain thrusts into the North Sea. Prasutagus was a client king, but his loyalty to Rome did not blind him to the corruption and greed of imperial officials.

Prasutagus was concerned that his two daughters might be disinherited after his death. To prevent this from happening he left half of his estate—in effect, half his kingdom—to the Roman Emperor Nero. The other half would be left to his daughters, that they might be able to maintain their status and dignity as British native royalty.

King Prasutagus died around ad 60, setting off a chain of events that led to the great revolt. The kingdom of the Iceni seemed vulnerable, a plum ripe for the picking, and Catus lost little time in making his move. As a preliminary step, the procurator sent in a swarm of bailiffs to call in the various loans that the British nobles owed the Roman moneylenders. Payment was demanded in full, and when the British debtors could not pay, as was often the case, their lands were seized and they themselves often reduced to slavery.

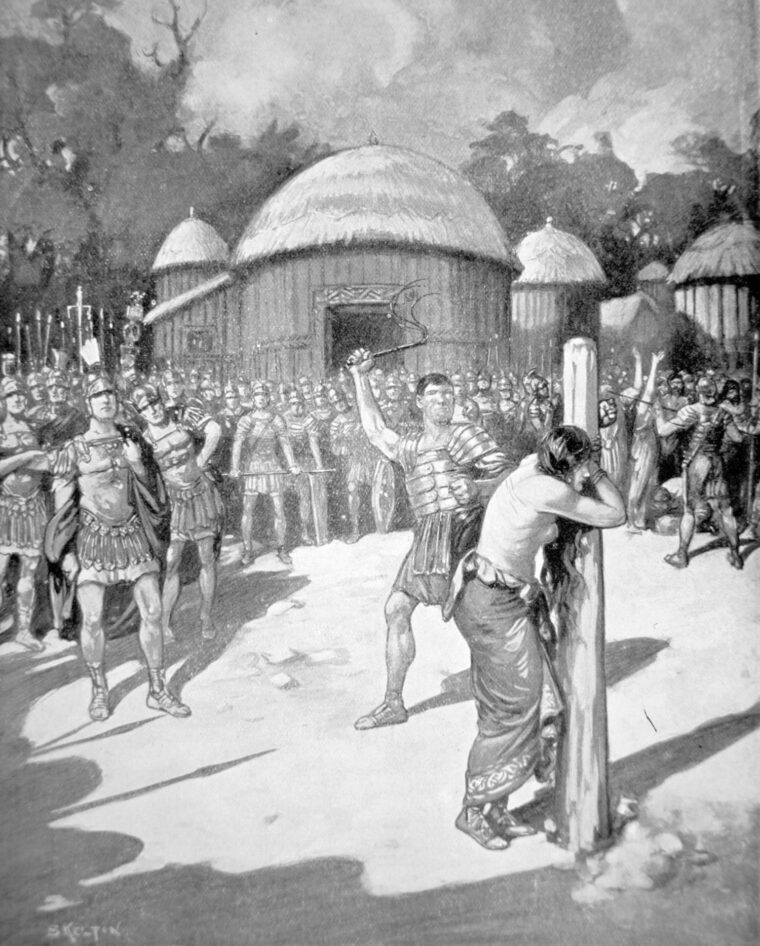

Prasutagus was reputed to be a weak king, but his consort was made of sterner stuff. Boudicca was in her thirties in ad 60, a tall, redheaded woman with a keen intelligence and the soul of a warrior. Even the Icenian royal family was not exempt from Roman depredations, because Catus soon seized all of the late king’s estates. Boudicca was outraged, and when she forcefully protested against Roman actions Catus had her flogged.

Roman flogging usually involved a whip called a flagrum, a “cat-o-nine-tails” arrangement that featured bits of bone or metal sewn into the tips of each leather strip. Pieces of flesh were gouged out with each stroke; the severe trauma, accompanied by shock and loss of blood, usually left the victim dead or close to it. Boudicca was probably beaten with rods instead—a “lighter” punishment that still would produce terrible lacerations on a woman’s body. Romans also raped her two daughters, an act of calculated political brutality. By ravishing the two princesses, they cruelly demonstrated their mastery over all Britons, at the same time lessening the girls’ value as royal wives.

Catus and the Romans departed Iceni lands loaded with slaves and plunder. The procurator probably went to Londinium, satisfied he had thoroughly cowed the natives and broken their will. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Shortsighted Roman policies and arrogance laid the tinder of rebellion, but Catus had provided the spark to ignite it. Boudicca herself would provide the leadership needed for the campaign. Celtic women were strong, and it was not uncommon for them to take up arms and do battle shoulder-to-shoulder with their men.

Boudicca’s first target was Camulodunum, the capital of Roman Britain, also called Colonia Victricenus or City of Victory. Camulodunum predated the Roman occupation, and originally was a principal town for the Trinovantes people. As soon as the Romans arrived they built a legionary fortress to secure the area. The crack XX Legio Valeria (“Valiant”) provided the garrison for many years. In ad 49 the XX Legio was reassigned, and with its departure a new Romanized Camulodunum took root.

It was established Roman policy to populate such cities with retired Roman veterans. Swords were turned to plowshares, and former legionaries became local farmers. But Roman civilization was essentially urban, so a new Camulodunum arose from what was formerly clusters of huts. Streets were laid out on the grid plan, and administrative buildings, baths, and shops quickly arose.

A Temple of the Deified Claudius was soon built, probably after the Emperor’s death in ad 54. It was a magnificent structure, built on a podium and featuring a forest of stately columns crowned by ornately sculpted Corinthian columns. The great temple was surrounded by a kind of sacred precinct that covered approximately 108 acres.

But all this magnificence cost money, and much of the financial burden was shifted to the long-suffering Trinovantes peasantry. The temple had its own official priesthood, who pillaged the countryside, then excused themselves on the grounds of religious zeal. Peasants were already crushed by the burden of heavy Roman taxes; now rapacious Claudian priests swooped down to devour what was left.

To the Romans the temple was a benign symbol of a benevolent empire, but to the Britons it was a hated expression of slavery and British subjugation. The Roman colonists made things worse with their utter contempt for their British neighbors. Perhaps not all colonists were like this, but the majority seemed to think the Britons were little better than animals, fit only to serve their Latin-speaking masters.

It was little wonder, then, that the Trinovantes tribe eagerly joined forces with the advancing Iceni. The Romans were a superstitious people, ever ready to read the will of the gods in signs and portents. It was said that the statue of Victory at Camulodunum toppled face forward into the dirt, as if yielding to the enemies of Rome. There were also strange voices heard, and ghostly cries and lamentations filled the city’s theater.

The Camulodunum city council met in emergency session to determine a course of action. The city was completely unfortified. The old Legionary fortress walls had been torn down or filled in, leaving Camulodunum utterly defenseless. Worse still, there were few active- duty soldiers in the area, though of course most of the male population were veterans who knew how to wield a sword or throw a pilum.

Since Suetonius was still in Wales, the next best thing would be to appeal to Procurator Catus, who was probably about 60 miles away in Londinium. Messengers were dispatched to Catus urging him to take action, but the Procurator sent only 200 men. It was clear Camulodunum was on its own, and the situation was made worse by the fact that many of the city’s British inhabitants were Boudicca sympathizers

Faced with discontents from within and attack from without, the Romans did the best they could. It was decided that the Temple of Claudius would be fortified as a redoubt and place of refuge if rebel forces managed to break into the city.

Boudicca’s army was large, and growing larger by the day. When she appeared outside Camulodunum, she might have had a host as large as 100,000. The Britons attacked at once, and the fighting was heavy. The Romans defended their city street by street, and house by house, until finally the sheer weight of numbers forced them to fall back to their temple redoubt.

Camulodunum was sacked and burnt so thoroughly that traces of soot and scorching remain to this day. Houses were looted, then consigned to the flames. Some Roman captives were killed at once, while others were tortured before being dispatched. As the flames spread, leaping orange-red tendrils produced coils of smoke that blackened the sky. Blood-spattered Britons thronged through the stricken city, carrying armfuls of plunder. But Boudicca knew the temple area had to be taken before their victory was complete.

The Temple of Claudius held out for two terror-stricken days. Hundreds of Roman men, women, and children were huddled in its inner sanctuary, disheveled, exhausted, and fearful. No doubt many of the men had been injured in the fighting, and the moans of the wounded mingled with the cries of terrified children. Perhaps the more religious among them prayed to the cult statue of Claudius—a great figure that gazed down at the scene with impassive eyes—for succor and relief.

Petillius Cerialis, legatus legionus of the IX Legio Hispana, heard of the attack on Camulodunum and quickly decided to march to its relief. But would he make it in time? His legionary camp was some 80 miles north of the city.

Sated with spoils and the thrill of freedom, the Britons stormed the temple redoubt after the two-day siege. The Romans inside fought with the valor of desperation, but the issue was never really in doubt. Without relief, the temple redoubt could not hold. Once they cut their way into the inner sanctuary, the Britons killed everyone inside without mercy. When the last Roman was killed, the cult statue of Claudius was pulled down, then the whole temple put to the torch. Flame shot from between the columns, and soon the temple was transformed into a giant funeral pyre for the hundreds of Roman bodies that lay sprawled within.

The capital of Roman Britannia was in ruins, but there was still one more piece of unfinished business to attend to. Scouts brought Boudicca word of the IX Legio’s approach, so the wily British queen made plans to ambush the unsuspecting Petillius Cerialis.

Roman legions nominally had 5,000 men, but few legions were up to full strength. The IX Legio Hispana had apparently been weakened further by units being sent on various detached duties. Petillius Cerialis was leading a vexelatio, which meant a scratch unit of indeterminate size created for a specific task. Estimates vary, but he might have had around 2,500 men, clearly inadequate for the task in hand. It is possible the Britons attacked the Romans in a heavily wooded area, where Roman discipline and superior tactics would be neutralized.

The Britons attacked on all sides, and it is possible the Romans were ambushed while still in column along the line of march. Surrounded on all sides, outnumbered many times to one, the IX Legio Hispana stood and died in its tracks. The Roman infantry was cut down to the last man, but a chastened Petillius Cerialis managed to cut his way though and escape with the cavalry. Perhaps 2,000 legionaries died in this debacle.

In the meantime, Suetonius Paulinus was marching southeast to Londinium. Suetonius divined—correctly—that the city on the Thames would be Boudicca’s next target. If Camulodunum was the capital of Roman Britannia, Londinium was its commercial heart. If Londinium fell, it might provide the momentum that would expel the Romans forever,

By virtue of hard marching Suetonius managed to reach Londinium before Boudicca. This was quite a feat, and the Roman possibly accomplished it because Boudicca herself delayed. When he began the march south Suetonius was over 250 miles from Londinium, Boudicca only 60 miles. The governor beat Boudicca to Londinium, but once he arrived he saw he would be forced to make some tough decisions.

Londinium was home to perhaps 30,000 people, but had no walls and was virtually defenseless. There was no time to mount an adequate defense, or even construct decent fortifications. If Suetonius abandoned the city, Roman prestige might suffer a temporary eclipse—but better to lose face than to lose a province. It was also a political gamble; the Emperor Nero might not look kindly on a commander who seemingly was in constant retreat. But in military affairs the right decisions are often the most painful and controversial ones. Suetonius was prepared to accept the consequence, even it mean disgrace, death, or exile at the emperor’s hands.

When the citizens of Londinium heard that Suetonius was going to abandon the city without a fight, they crowed around him with tears and supplications, begging him not to leave. Suetonius’s mind was made up, but he offered protection to any and all who would accompany his army. Many chose to leave, but others did not. Some did not want to leave their homes and businesses, created after a decade of hard work. Some women felt they could not stand the rigors of the march and elected to stay. Still others were sick or too old. And, of course, there was the city’s criminal fringe, who saw an opportunity to loot abandoned homes and make a clandestine profit.

Boudicca and the avenging army came down on Londinium like furies, destroying everything in their wake. Once again, most buildings were put to the torch. It was as if the flames were a purifying agent, cleansing British soil of Roman pollution.

The Thames was much wider than it is today; in fact, it was perhaps three times as broad. Recently archaeologists have uncovered burnt remains at Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames. This is an interesting revelation, because it suggests that Roman London straddled both banks of the river. It also suggests that there might have been a London Bridge of some kind in ad 60. Conventional wisdom suggests that the bridge was built after the revolt.

Throughout the rebellion the fate of Roman captives was terrible indeed. Those not immediately slain were reserved for torture or sacrifice in the Druids’ sacred groves. Roman historians record that Roman women captured by the Britons were stripped naked, their breasts were cut off, and then they were impaled on long stakes lengthwise through the body. Intentional or otherwise, the impaling is a cruel parody of the Roman rape of Boudicca’s daughters.

Once Londinium was in ruins, Boudicca’s forces moved on to Verulanium (today’s St. Albans) and utterly destroyed it. Many Britons in Verulanium were becoming Romanized, which made them traitors in Boudicca’s eyes. Everyone in Verulanium, Roman and Romanized Briton alike, was put to the sword. But Boudicca knew that Britannia would not be truly liberated until Roman field forces were defeated. In her burning desire for retribution and revenge, Boudicca had focused on the cities, those outward signs of Roman occupation. But Roman power in Britain was based on the Roman legions.

Governor Suetonius also instinctively knew a confrontation was coming. He decided to make a stand in the Midlands and ordered all available units to rally to his eagles. Poenius Postumius, commander of the II Legio, decided to ignore the governor’s summons, either in a fit of pique or professional jealousy. This left Suetonius so few men there was a chance that even superior Roman discipline, tactics, and weapons could not make up the difference. The governor could gather under his command the XX Legio Valeria, the XIV Legio Gemina, and the elements of the decimated IX Hispana (such as the cavalry), plus some auxiliary units—perhaps 10,000 men in all

Roman writers claim that Boudicca had 200,000 men by this time, perhaps even more. Ancient chroniclers tend to inflate figures, but probably the Romans were outnumbered 10-to-1 at the very least. Suetonius had a keen eye for ground and used this talent to pick the best possible positions for his army.

The governor placed his army in a narrow defile that was surrounded on three sides by dense woods. It was ideal, because the woods protected the Romans’ vulnerable flanks and rear. Legion heavy infantry formed the Roman center, with the auxiliaries on hand to provide close support. The Roman cavalry was positioned on the right and left wings.

By contrast, Boudicca’s army was an amorphous mass of humanity, seemingly without organization or leadership. Thousands of Celtic warriors shouted war cries, their collective voices producing a low, rumbling roar. British women were on hand as well, adding their voices to the auditory assault on Roman ears. Their high-pitched screams, combined with the men’s deeper shouts and the rattle of drums, produced a sound of chilling terror.

The Britons’ appearance was no less frightening than their war cries. Some warriors wore tartan pants, their upper torsos tattooed or painted blue. Others sported hair that was daubed with clay to produce fearsome spikes, while others fought completely nude, wearing just a torque necklace around their throats. British chariots were also on the scene, wheels and galloping horses kicking up clods of earth as they raced about.

A vast semicircle of wagons was just behind the rebel army, filled with warrior families there to witness Boudicca’s triumph and add their shouts to the general tumult. It was a British Celtic custom for noncombatants to observe their army’s glorious deeds, and anti-Roman feeling was at a fever pitch. The sacking of three Roman cities and the defeat of the IX Legio seemed to augur even greater triumphs ahead. It seemed as if the Britons were but one step away from freedom and independence. Just one more battle, and the Roman yoke would be cast aside forever.

Queen Boudicca then appeared in her own war chariot, brandishing a spear and accompanied by her two teenage daughters. She was dressed in a tartan tunic with a cloak flung over her shoulders and fastened by a brooch. A cascade of reddish-brown hair tumbled to her waist, and her neck was circled by a golden torque, that distinctive emblem of Celtic culture. She was very tall, and when she spoke her booming voice carried far and wide.

Apparently Boudicca drove through the assembled masses of Britons, temporarily quieting them. She addressed each tribal unit in turn, reminding them of past victories and the justice of their cause. She also reminded them that “This is not the first time that the Britons have been led in battle by a woman.” But this was not merely a battle chief, or even a queen, but a woman whose body bore the terrible scars of Roman injustice. “On this spot,” she concluded, “we must conquer, or die with glory. My resolution is fixed. The men, if they please, may survive with infamy and die in bondage.”

Governor Suetonius also addressed his men, to rally them and give them fresh courage for the coming ordeal. He urged them to turn a deaf ear to the “savage uproar, the yells and shouts of undisciplined barbarians…. Keep your ranks; discharge your javelins; rush forward to close attack, bear down with all your shields, and hew a passage with your swords.”

The battle began when the mass of Britons launched their spears, then closed for the kill. The Roman infantry stood shoulder to shoulder behind their shields, each rectangular scutum so close to its neighbor that from a distance they seemed to form an unbroken red wall. The Roman auxiliaries discharged flights of arrows, the lethal shafts thinning British ranks but not breaking them. At a signal the Roman infantry threw their pila, light spears that streaked through the air with swiftness and grace.

The pila lanced into arms, chests, and stomachs, inflicting bloody wounds, but these impaled victims were byproducts of a much larger design. The pila were designed to disorder an enemy’s line and strip him of his protection. The Roman pila thudded into British shields, bending but not breaking. Once a shield was pin-cushioned, it grew cumbersome and heavy. Such a shield was usually tossed aside, leaving its owner vulnerable.

The order was then given for the Romans to advance. They created a wedge formation with its armored tip aiming straight at the surging Britons. The Romans went forward, their well-trained movements and inexorable advance making them seem more like machines than men. As they closed, the legionaries drew their swords, thousands of blades rasping out of scabbards as if from one man. The Roman infantryman was basically a swordsman, and his weapons and armor were designed for such close-in work.

The Roman wedge was a fearful thing to behold, the serried ranks sparkling as sunlight reflected off helmets and armor.

Roman swords slashed and stabbed their way through the multitude, whose number now became a disadvantage. The British ranks were so packed that the warriors could not properly wield their long swords. The legionaries coordinated sword and shield movements with the clockwork precision born of long training and iron discipline The Roman wedge cut through the mass of British warriors like a prow of a ship cutting though the sea.

Courageous as they were, the British could not stand up to this Roman killing machine and began to waver. Finally, their momentum spent, Boudicca’s army began to break, as thousands of men began a headlong flight to safety. The hundreds of spectator wagons, originally brought to serve as platforms for watching a British triumph, now formed an effective “dam” to bar escape. Caught between the wagons and the oncoming Romans, thousands were felled where they stood.

The Romans slaughtered every man, woman, and child that fell under their bloodstained swords.The Roman historian Tacitus, writing with customary brevity, simply states that “neither age nor sex was spared.” It is estimated that 80,000 Britons were slaughtered during the battle and its immediate aftermath. Tacitus estimates Roman casualties at 400 dead, and less than 400 wounded.

Boudicca was not among the slain. Seeing all was lost, the courageous British queen took poison. She had already experienced Roman cruelty, and knew what her fate would be if taken alive. She would have been taken to Rome, displayed in chains, and then most likely strangled in prison. Apparently her daughters joined her in suicide.

When he heard of the great Roman victory, Poenius Postumius was filled with guilt and remorse. Because of his petulance, his II Legio was denied glory in battle. He could have shared in the victory; now he suffered ignominy for his disobedience to orders. Racked by guilt, Postumius drew his own sword and killed himself. By contrast, the XX Legio and XIV Legio were honored for their part in suppressing the Icenian rebellion. The former was now called “Legio Vicesimae Valeria Victrix” (The Twentieth Legion, Valiant and Victorious”) for its role, while the latter was now dubbed “Legio Quattordecimae Gemina Martia Victrix (The Fourteenth Legion Twin, Martial and Victorious).

Roman mopping-up operations were as brutal as they were thorough. Troops raged through Iceni lands, scouring them with fire and sword. The fires of rebellion that had once burned so brightly were extinguished in showers of blood. The Romans were capable of mercy and reconciliation, but not after such a serious threat to their rule. Rebellion had to be rooted out, thoroughly extirpated, and the surest way was to slaughter rebels and reduce the survivors to slavery.

But after the “stick” came the “carrot.” Although the Romans could be brutal, they were also supreme in the art of government. It was recognized that the Romans themselves were responsible for the rebellion, and steps were taken to reform the situation. The viciously cruel Catus was replaced as procurator by a Romanized Gaul from Trier named Classicianus. Classicianus took a more conciliatory, reformist approach, and his efforts bore some fruit. Suetonius was replaced as governor by Pretonius Turpilanius, who adopted a course that was also more conciliatory, more sensitive to native British culture and society.

In time, Britain became an integral part of the sprawling Roman Empire. By the second and third centuries ad the process of Romanization was quite advanced and the province prospered. The three destroyed cities rose from the ashes more beautiful and prosperous than before. In fact, Londinium recovered so rapidly it soon replaced Camulodunum as capital of Roman Britannia.

Although the Romans had triumphed, their historians were honest enough to record the events exactly as they happened. They acknowledged Roman injustice, while at the same time giving full credit to a courageous enemy. Boudicca’s memory remained fresh, thanks in part to a lingering folk memory and the writings of great Roman authors like Tacitus.

In the 19th century the Victorians romanticized the Icenian queen, celebrating her as Britannia incarnate. In 1902 a statue of Boudicca was erected in London near the Houses of Parliament. The statue is still there today, the queen standing erect in her chariot, her daughters by her side. The bronze figure stands tall and proud, the very embodiment of a woman who refused to yield to tyranny and oppression.

Eric Niderost, a frequent contributor to Military Heritage, is a community college professor in Hayward, California.

The final battle was a demonstration that fighting as an army had a great advantage over a foe that fights as a group of individual soldiers. Roman discipline, as it had previously against tribes in various parts of the empire, triumphed against enthusiastic but poorly organized mobs of individual fighters. The Roman effort was successful for almost three centuries until the Roman garrison was called home to defend against the Goths and the Vandals in 410 AD.