By William E. Welsh

One of the smoothbore cannons in Captain Merritt B. Miller’s Third Company of the Washington Artillery deployed west of Emmitsburg Road just south of the town of Gettysburg fired a single round at 1:07 p.m. as a signal for the Confederate bombardment of Cemetery Ridge to begin.

Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, at the request of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, had toiled all morning to assemble and position 170 cannon from all three Confederate corps to participate that afternoon in the largest cannonade ever undertaken on the North American continent.

The target of the Confederate rifled and smoothbore cannon was a 500-yard section of Cemetery Ridge, a low elevation in the cultivated landscape that rose just 40 feet above the surrounding terrain. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the Union commander, had assigned the Union II Corps to defend the position, which occupied the center of the Union army’s fishhook-shaped battle line.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock, who commanded the II Corps, had five batteries of cannon under his immediate control, organized into an artillery brigade. Meade also issued orders for additional batteries to be drawn from the Army of the Potomac’s artillery reserve to deploy in support of the II Corps. More Federal batteries belonging to the Union I Corps occupied the ground north of Hancock’s corps, which included Cemetery Hill, a commanding height that rose 500 feet above the town of Gettysburg.

General Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, intended the bombardment to precede an infantry attack by 13,000 Confederate soldiers in two-and-one-half divisions. The purpose of the bombardment was to destroy as many of the Federal batteries as possible, as well to demoralize the infantry that would sweep towards a conspicuous grove of scrub oaks on the north end of the ridge, known afterwards as the Copse of Trees. Once they had breached the Union line, the attacking Confederate infantry would wheel left to assault and capture Cemetery Hill, which was the key to the entire Union position.

As the Confederate bombardment grew in intensity, a storm of iron shot and shell slashed into the ridge and its reverse slope. The temperature nearly reached 90 degrees on the third day of the battle, and the searing heat did not disperse the smoke from the cannonade and the Union army’s counter-battery fire that lay thick upon the ridge.

Of the five batteries belonging to Hancock’s artillery brigade, Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing’s suffered the heaviest damage. The 22-year-old officer had graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in June 1861 and immediately received his commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. 4th Artillery. He commanded Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery, which was equipped with six 3-inch ordnance rifles.

The Confederate bombardment on its position lasted for two hours, and during the course of the barrage, Cushing suffered shrapnel wounds to both his shoulder and groin. Sergeant Frederick Fuger, who became the next-in-command after two other lieutenants in the battery became casualties, implored him to go to the rear, but Cushing dismissed the request. “No, I stay right here and fight it out or die in the attempt,” he replied.

Cushing was born in 1841 in Delafield, Wisconsin. When his father died prematurely, his mother moved the family to Fredonia, New York, to be near relatives. Cushing entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1857. Upon his graduation in June 1861, he reported immediately to Washington, D.C., where he trained enlisted artillerymen and joined the Army of Northeastern Virginia in its advance to First Bull Run.

Cushing did a stint as an ordnance officer in the service of Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner during the Peninsular Campaign in spring 1862. In the Fredericksburg campaign, he again served Sumner, who commanded the Right Grand Division, as a topographical engineer.

He received command of 4th U.S. Artillery, Battery A, in time for the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, where his battery was assigned to Maj. Gen. Darius Couch’s II Corps.

The reorganized Union II Corps, with Hancock as its new commander, arrived in Taneytown, Maryland, on the morning of July 1. The town was 14 miles from Gettysburg, a place in southern Pennsylvania where 10 roads came together, making it of particular strategic importance.

The soldiers of the Union II Corps awoke at 3:00 a.m. on July 2 and marched off to Gettysburg from their bivouac north of Taneytown. They arrived at the battlefield after sunrise at 5:40 a.m. They left Taneytown Road and marched across the farmland to Cemetery Ridge. Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s division assumed a position on the right side of the II Corps line of battle on the north end of the ridge. Gibbon placed Brig. Gen. William Harrow’s brigade on the left, Colonel Norman Hall’s brigade in the center, and Brig. Gen. Alexander Webb’s brigade on the right next to the I Corps.

Gibbon had under his direct command two artillery batteries. He ordered Lieutenant Frederick Brown’s 1st Rhode Island, Battery B, which was outfitted with six 12-pounder smoothbores, to support Hall’s brigade and Cushing’s battery to support Webb’s brigade.

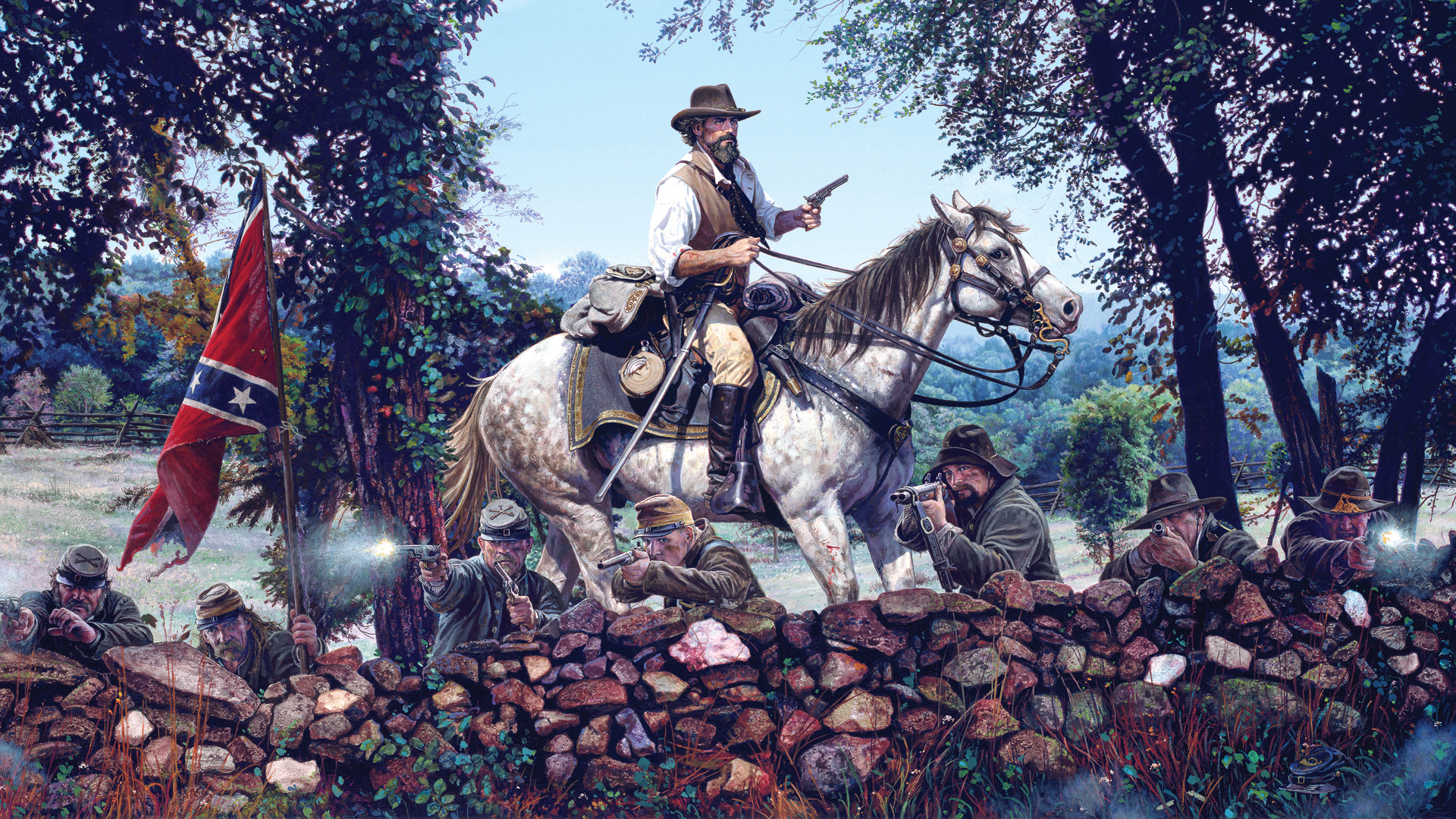

Webb’s brigade, composed mostly of Irish immigrants from Philadelphia, occupied a weed-choked field at a place where a low stone wall that marked property boundaries ran south along the crest of the ridge, turned west for 100 yards, and then turned south again parallel to the ridge. This area became known afterwards as “The Angle.”

Cushing’s battery had a core of regular army veterans and was rounded out by infantrymen who had transferred into the artillery branch. He had personally trained them, and, like most good commanders, he was a strict disciplinarian. The patch of ground that would serve as their position in the battle was full of brush and rocks, so Cushing immediately put his men to work clearing the ground for the battery’s rifled guns, caissons, and horses.

In the late afternoon of July 2, the Confederate II Corps and one division of the III Corps attacked the Union left flank. At 6:00 p.m. Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright’s Georgia Brigade of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s III Corps division attacked Gibbon’s center. Two regiments from Hall’s brigade and one from Webb’s advanced to head off the attack, and the action soon got heavy enough for Webb to commit his whole brigade against Wright’s left regiments. Three artillery batteries from the II Corps, one of which was Cushing’s, went into action to support Gibbon’s infantry and ensure that they soundly repulsed the Georgians, as well as Brig. Gen. Carnot Posey’s Mississippi brigade, which had attacked in a half-hearted fashion to the left of the better-led Georgians.

“We met the charge [of the Georgians] with such a destroying fire that they were forced back in confusion,” wrote Anthony McDermott of the 69th Pennsylvania, one of the four regiments in the Philadelphia Brigade. “Their lines were broken and thinned as we poured volley after volley into their disordered ranks until they were a dispirited mob.”

The Georgians overran part of Brown’s battery; however, the Union infantry recovered all but one artillery piece. Wright complained bitterly afterwards that his attack had not been well supported. He lost 873 of his 1,450 men.

Longstreet, the commander of the Confederate I Corps, had sent orders at 9:00 a.m. to Colonel Alexander, to whom he had entrusted the task of overseeing the placement of the Confederate guns.

Four hours later, the Confederate artillery and infantry were in position for what would famously be known afterwards as Pickett’s Charge.

Gibbon’s division would withstand the worst of the Confederate attack. Cushing’s battery was just below the crest of the ridge on the morning of July 3, positioned between the 71st Pennsylvania and the 72nd Pennsylvania of Webb’s brigade. Just to the left of his line of fire, the 69th Pennsylvania manned the stone wall in front of the Copse of Trees. In keeping with standard practice for artillery batteries of the time, the limbers were in a second line behind the guns, and the caissons in a third line behind the limbers.

The battery’s position and that of Gibbon’s division overlooked farm fields on the broad plain between Seminary and Cemetery Ridges. Emmitsburg Road was in no-man’s land between the opposing forces. Wooden fences bordered both sides of Emmitsburg Road. To the advancing Confederates, the fences posed an obstacle that would prolong their exposure to Union artillery fire as they made their advance.

As the shells and case shot rained down on Gibbon’s division, infantrymen and artillerymen alike scrambled for whatever cover they could find. Cushing and the other Union battery commanders along Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill shouted to their gunners to man their artillery pieces. In a matter of minutes, the Union guns began firing back at the Confederate batteries. Although many of the Confederate artillery crews overshot Cemetery Ridge with their fire, enough landed squarely on the crest to cause considerable damage to the Union batteries. Caissons exploded, guns were dismounted, and carriages and limbers broken and shattered.

When the wheel of one of his guns collapsed, the artillerymen manning it scattered. Cushing furiously rushed over to the men to force them back to their gun. He drew his pistol and threatened to shoot any of his artillerymen who abandoned their gun without his permission. Working feverishly, the men installed a spare wheel onto the gun.

The young lieutenant Cushing, seasoned by many battles, maintained his cool demeanor throughout the ordeal. After identifying targets, he gave commands to the other lieutenants and sergeants supervising the gun crews that adjusted the battery’s fire. “He was … talking to the boys between shots with the glass constantly to his eyes, watching the effect of our shots,” wrote one of his men. As the bombardment wore on, the slashing shells from the Confederate artillery knocked out four of Cushing’s six guns.

When the bombardment was over, Cushing found that he had only two serviceable guns and not enough men to work them, so he requested volunteers from the Pennsylvania Brigade to assist him. He then asked Webb for permission to run the guns up to the wall and have them interspersed with the soldiers of the 69th Pennsylvania, who had extended their line north deep into the Angle. The cool-headed general, who had remained standing through the entire bombardment leaning on his sword and puffing on a cigar, approved the decision.

Cushing ordered extra rounds of canister, an anti-personnel round in which iron balls were packed in a tin can and sprayed out upon leaving the muzzle of the gun, stacked next to his guns. As the advancing tide of gray-clad soldiers swept forward, Cushing directed every canister round fired at the Confederates as they surged uphill from Emmitsburg Road towards the stone wall in the Angle. The Confederates closing on the wall belonged to the Virginia brigades of Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett and Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead. When the Virginians came to within 100 yards of the wall, Cushing ordered the gun crews to switch to double canister.

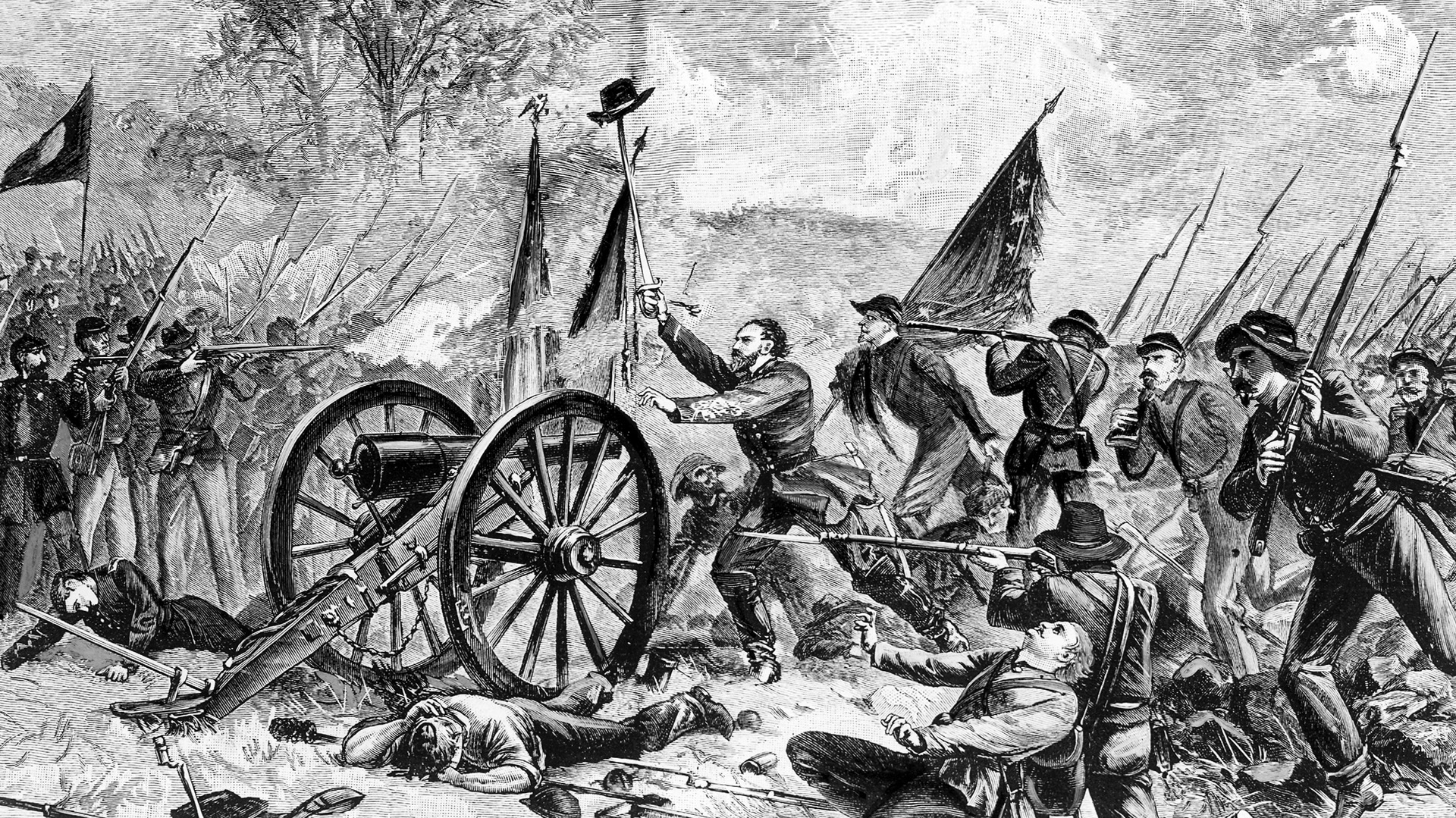

The Confederates were coming on fast, and some of them loaded and fired as they advanced. When the Confederates storming the position were just about to overrun the battery, Cushing shouted to Fuger that he would give them one more shot. As he grasped the lanyard to fire the artillery piece, a Confederate bullet struck him through the mouth, killing him instantly. Cushing fell over the handspike that was used to move the gun trail. His body was carried to the rear by Union soldiers.

Cushing was buried at West Point. In those days, the Medal of Honor was not given to soldiers who died posthumously during the Civil War. A Wisconsin resident, Margaret Zerwekh, who lived on land once owned by Cushing’s father, contacted Wisconsin members of Congress in the late 1980s requesting that Cushing receive the Medal of Honor. He was formally nominated for it in 2002, and the U.S. Army approved the nomination in 2010. President Barack Obama presented the Medal of Honor in a 2014 White House ceremony attended by Cushing’s descendents.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments