By Mike Phifer

A cold rain was falling as Confederate Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler led his brigade of horse soldiers north from the Confederate position at Stones River at midnight on December 29, 1862. Cutting around the Federal Army of the Cumberland’s left flank, which had been slowed in its advance from Nashville during the past three days by Wheeler’s cavalry and muddy roads, Wheeler planned to strike the Yankees from behind. General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, had ordered his cavalry commander to harass the Federal army’s supply lines. Wheeler did just that.

At dawn on December 30, Wheeler’s men struck 64 heavily laden supply wagons. Word of the raid brought two Federal regiments to the scene, intending to drive off Wheeler, but instead they were forced back. With 20 wagons sending billowing smoke skyward, the raiders moved on and struck an encamped supply train at La Vergne, Tennessee. This time 200 wagons were aflame. In addition, the Confederate raiders dispersed 1,000 mules into the countryside and paroled 400 soldiers.

Wheeler was not done yet. Well behind Yankee lines, Wheeler and his men destroyed a third wagon train. Continuing on, the raiders took more wagons and ambulances. After stopping for much needed rest, Wheeler and his troopers were back in the saddle by 2 am on December 31 and at midday splashed back across Stones River. Wheeler and his men had done an admirable job of damaging the Army of the Cumberland’s fragile supply line.

That same day at Murfreesboro, Bragg’s infantry drove Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Federal army back five miles. Success seemed imminent but, as Wheeler and the rest of the Army of Tennessee were to learn, the Yankees were not beaten yet. Wheeler would soon find himself in a role he would play often in the Army of Tennessee, which was acting as its rear guard under orders to slow the Union advance.

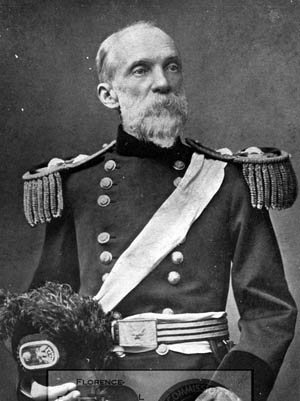

Wheeler was born in 1836 in Augusta, Georgia. His parents were originally from New England. After his father had financial difficulties and his mother died, young Joseph and his family moved back to Connecticut in the early 1840s. Joseph went to school there and after graduation moved to New York City where he became a clerk in a mercantile office. In 1854, he was accepted into West Point.

Graduating in 1859 near the bottom of his class, Brevet Second Lieutenant Wheeler was assigned to the 1st United States Dragoons and reported for duty at Cavalry School of Practice at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. A year later, Wheeler was ordered to New Mexico Territory where he was assigned to the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen. On his journey to Fort Craig, he earned the nickname “Fighting Joe” when he helped break up an attack by Apaches.

His tour of duty in the West lasted until 1861. With war looming, Wheeler sided with the South despite his family ties to the North. Although he loved the Union and his position in the U.S. Army, he told his brother, he would resign if Georgia withdrew from the Union. A little more than a month later Georgia did just that and Wheeler submitted his resignation on February 27, 1861.

Less than two months later, Wheeler was appointed a second lieutenant of artillery in the Confederate regular army. He was sent to Pensacola, Florida, where his competence and ability brought him to the attention of Trans-Mississippi departmental commander Bragg. Wheeler was soon promoted to colonel and given command of the 19th Alabama Infantry Regiment at the urging of the officers of that recently formed unit to Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin. Bragg was unhappy with the promotion, though, because he believed Wheeler should not have been promoted over other officers with more experience.

Wheeler drilled his new unit relentlessly. The constant drilling turned them into the well-honed regiment that he would lead into action at Shiloh on April 6, 1862. As part of Brig. Gen. John King Jackson’s brigade, Wheeler and his men were in the thick of the fighting.

A combined force of cavalry and infantry under Wheeler’s command acted as a rear guard for the Army of the Mississippi as it retreated toward Corinth, Mississippi. During the month-long siege of Corinth, which began on April 28 and ended on May 30, Wheeler helped fend off Union probes. When the army evacuated Corinth, Wheeler once again helped cover its retreat as it marched south to Tupelo.

On June 17, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Bragg as commander of the Western Department, which included the Army of the Mississippi. As part of Bragg’s reorganization, he appointed Wheeler on July 13 to serve as his chief of cavalry. Wheeler ordered his troopers to rendezvous at Holly Springs, which lay 60 miles north of Tupelo. Wheeler then led his brigade through western Tennessee. The troopers burned railroad bridges to disrupt Union supplies and clashed with Union forces on eight occasions.

Wheeler helped keep the Union forces off balance throughout the late summer while Bragg marched his army east to Chattanooga, Tennessee, in preparation for an invasion of Kentucky. In August, Wheeler led his cavalry through central Tennessee, covering the west flank of Bragg’s army. Wheeler performed well during the march into Kentucky, scouting and battling the Federals. Following the Confederate retreat in the aftermath of the Battle of Perryville on October 8, Wheeler once again covered the army’s retreat.

Fanning out to cover the flanks and rear of the retreating army, Wheeler’s men felled trees across the muddy roads to slow the Yankee pursuit. Fighting and falling back grudgingly in rearguard actions, Wheeler used his men as mounted infantry when necessary. During the roughly two-month period from late August to late October, Wheeler’s men fought 45 skirmishes in support of Bragg’s army. For his superb performance, Wheeler was promoted to brigadier general on October 30.

During the Stones River campaign from December 26, 1862, to January 5, 1863, Wheeler once again performed ably, launching hit-and-run attacks with his cavalry on Union wagon trains laden with supplies. During the raids, Wheeler destroyed hundreds of wagons and captured 700 prisoners. For his valor, Wheeler was promoted to major general on January 20. With the increase in rank, Wheeler now found himself in command of every cavalry unit in middle Tennessee, including Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s troops.

In late January, Wheeler set off with about 2,000 troopers to again interrupt Federal navigation on the Cumberland River. Along the way, Forrest with 800 men joined him. Unfortunately, the Federals were aware of Wheeler’s presence and purposely avoided sending vessels upstream on the Cumberland. For that reason, Wheeler decided to strike the Federal base at Dover, Tennessee. The Yankees repulsed the February 23 attack.

After the Yankees refused a Confederate demand for surrender, Wheeler ordered his guns to hammer the post. “Little Joe,” as he was also called, planned to launch a coordinated attack with Brig. Gen. John Wharton and Forrest’s dismounted troopers. Forrest, who assumed the Yankees were abandoning the place, ordered his men to mount up and charge. The Federals met the screaming Rebels with withering rifle and artillery fire that shattered the attack and killed or wounded almost a quarter of Forrest’s men. Forrest dismounted his men and joined Wharton’s attack , which achieved some success at first but could not breach the Federal earthworks. With casualties mounting, Wheeler called off the attack. Dover remained in Federal hands.

Forrest was in a foul mood. He had objected to the attack before it began. “I mean no disrespect to you,” he told Wheeler. “You know my feelings of personal friendship for you; you can have my sword if you demand it; but there is one thing I do want you to put in that report to General Bragg, tell him that I will be in my coffin before I will fight again under your command.”

Wheeler declined to take his sword. “As the commanding officer I take all the blame and responsibility for this failure,” he told Forrest.

Wheeler spent the rest of the winter drilling his command, which as a result of new reinforcements reached corps strength. Interestingly, he used the manual, A Revised System of Cavalry Tactics, for the Use of Cavalry and Mounted Infantry, C.S.A., which he had written and that was published two years before the start of the war.

On June 27, at Shelbyville, Tennessee, with their backs to the Duck River, Wheeler’s 600 horse soldiers attempted to hold back a combined force of Federal infantry and cavalry. Wheeler and a detachment covered the retreat of the majority of Wheeler’s command before Little Joe ordered the detachment across the river as well. With Federal bullets whizzing past them, Wheeler and the last dozen troopers swam their horses to the south bank. It had been a close call, but they had gotten across to safety without being captured.

Bragg’s army retreated back to Chattanooga in early July with Wheeler and Forrest protecting its rear and flanks. Two months later Bragg evacuated the key town and fell back into Georgia along West Chickamauga Creek. The Army of Tennessee struck back, defeating the Rosecrans’s Army in a bloody two-day battle that began on September 19. On the second day, Wheeler’s command captured 1,000 prisoners, 20 wagons, and five field hospitals.

The Federal army retreated into Chattanooga, which Bragg soon besieged. Wheeler was ordered into the Sequatchie Valley through which ran a vulnerable Federal supply line. On October 3, Wheeler split his force of 4,000 exhausted troopers and two batteries of horse artillery. Wharton led the larger detachment toward McMinnville, Tennessee, to destroy a Federal supply depot, while Wheeler went after a Federal wagon train. Wheeler captured 32 wagons but soon came upon a 10-mile-long supply train. Wheeler bagged 1,200 prisoners and his men torched the wagon train. It was a grievous blow to the hungry Federals in Chattanooga. The blow was made worse when Wheeler rejoined Wharton at McMinnville the following day. The reunited command destroyed a locomotive and the attached railway cars.

Wheeler continued the raid by leading his command north across Stones River, destroying bridge and track as he went. On October 6, the Rebel raiders halted near Farmington, Tennessee. The next morning, Federal cavalry caught them, and a vicious fight ensued. Wheeler’s men barely held off the bluecoats. At nightfall, the weary Rebels slipped away and headed south for the Tennessee River. Wheeler’s men finally got some much needed rest in northwestern Alabama. While there, one of Wheeler’s aides penned a glowing report of the raid for a newspaper editor, referring to Wheeler as “War Child.” The story was soon printed, and Wheeler had yet another nickname.

A series of command changes occurred. Bragg resigned on November 29. Lt. Gen. William Hardee took temporary command on December 2, but two weeks later General Joseph Johnston replaced him as commander of the Army of Tennessee.

In early May 1864, Union General William T. Sherman, who commanded three Federal armies, began a slow but steady advance south towards Atlanta. Wheeler and his men played their usual role of scouting, raiding, and fighting rearguard actions. They were also, as one officer wrote, “digging ditches, building breastworks and lying in them for several weeks and the boys are already first-rate infantry.” Johnston was unable to stop Sherman. Davis replaced Johnston with the recklessly aggressive General John B. Hood, who took command on July 17.

In late July, Wheeler once again led his army north to disrupt Federal supply lines. Wheeler received information that multiple Union columns were operating in the region. One of these was Maj. Gen. George Stoneman’s cavalry force operating southeast of Wheeler, and the other was Brig. Gen. Edward McCook’s column that was working in tandem with Stoneman and operating southwest of Wheeler. One of the objectives the Federal cavalry columns had been given was to liberate prisoners from the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Neither would make it. Wheeler first caught up with McCook and defeated him on July 30 at Brown’s Mill near Newnan, Georgia. McCook’s force split up but was captured over the course of the next few days trying to return to Union lines. As for Stoneman, his command was beaten on July 29 by a much smaller force of veteran Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson at Macon, Georgia. Stoneman was taken prisoner two days later during the Battle at Round Oak, Georgia.

Wheeler’s men had not gotten much rest after defending the army’s supply line when they were ordered on a deep raid into Tennessee to disrupt Sherman’s supply line and, it was hoped, force him to retreat. On August 10, Wheeler set out with 4,500 men on a sweeping raid through eastern and central Tennessee. Little Joe’s raiders returned to Rebel lines in Alabama in mid-September after having severely damaged Sherman’s supply line. During the course of their raid, Wheeler’s horse soldiers had captured 600 prisoners, 200 wagons, 1,000 horses and mules, and a herd of cattle. But this did not deter Sherman. The tenacious Union commander, who enjoyed overwhelming numerical superiority, captured Atlanta on September 2.

For two weeks Wheeler rested his men in northwestern Alabama before returning to service. While Hood would soon lead the Army of Tennessee on an ill-fated invasion of Tennessee, Wheeler would lead his cavalry after Sherman, who was marching to Savannah.

After capturing Savannah in late December, Sherman turned his armies north for the Carolinas. Wheeler and his troopers, who by then were under the command of Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton, could do nothing to stop the Federal juggernaut. Rejoining the Army of Tennessee, once again under Johnston, they went into one of the final battles of the war at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19, 1865. During that battle, Wheeler commanded a cavalry corps under Hampton. The following month, Fighting Joe fought his last battle of the conflict on April 15 at Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Wheeler and Hampton later met up with Davis, who had departed the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, and was attempting to make his way to Texas where he hoped to continue the war. They were attempting to raise an escort for him when word reached them that Johnston had surrendered to Sherman on April 26 near Durham Station, North Carolina.

Wheeler did not consider himself bound by the surrender nor did his men, most of who had left for home. Raising a small corps of men, Wheeler set out to rendezvous with Davis, but he did not make it. Wheeler and his small band were captured by Federal cavalry.

Wheeler was paroled from Federal prison on June 8, 1865. He saw military service again during the Spanish-American War, both in Cuba and in the Philippines. During a battle in Cuba, Wheeler shouted, “We’ve got the damned Yankees on the run!” Both he and those around him broke into hearty laughter at the mistake. The famous Confederate cavalry general died in Brooklyn in 1906. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Go heler!

Read the story of General Wheeler,which was very interesting. I took my infantry basic in Camp Wheeler in Macon GA. Was this camp named for him? This was in July 1944 and was shipped out later to Germany for the battle of the bulge

Mr. Nungesser,

Yes, the camp was named for Joseph Wheeler. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_Wheeler

Would love to hear your stories of WWII, if you’re interested in sharing with another vet. [email protected]

V/r,

Ben

Interesting story, especially because I graduated from Joseph Wheeler High School in Marietta, GA near Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield so grew up hearing all about the local battles. https://www.cobbk12.org/wheeler/page/1662/about-school

What Confederate commanders lacked in numbers of troops they often made up for with daring, boldness, and tactical wiles. Gen. Wheeler is a perfect example of this. Thanks for the very informative article!

Yankees are fond of doing some tall running indeed

You mean like “running” the length of Georgia and through Richmond?

It’s amazing that the confederates won all the battles but still managed to lose the war and very badly lose the war. It’s a shame they were not smart enough to realize that they never had a chance of winning but deluded themselves with their own propaganda. But they sure were fond of running also when needs be. No shame in that. After the war they showed they never lost their knack for propaganda and making excuses.If they would have freed the POW’s at Andersonville my great-grandpa could have gotten home sooner. Captured in the battles of the Wilderness he spent time in 18 POW camps and named his 18 surviving children after each one. When he got home he looked like any survivor of a Nazi death camp.

Thank you for this marvelous story!

Well, they went wild when they credited Wheeler for “writing” cavalry manuals, both before and during the war.

Pick up a copy of “Wheeler’s Tactics.”

You will find—word for word—“Cooke’s Tactics,” plus “Maury’s Tactics“ (mounted infantry) tacked on the end. He didn’t even bother to change the page numbers. The only “edits” were removing the original author’s names.

Joe Wheeler is the only person I know of who served as a general in two different armies.

Fascinating telling of a true warrior with a superb tactical mind. He used his Calvary and his infantry to harry the Federals. Much like an air force does today with close ground support.

Had the CSA unlimited supply chain and reinforcements what would the outcome have been?