By Glenn Barnett

On the night of November 11, 1940, an event occurred that would change naval warfare for all time. The British Royal Navy launched a raid against the main base of the Italian Navy, the Regia Marina, at Taranto, located in the arch of the Italian boot. It was the first time that torpedo bombers, launched from an aircraft carrier, HMS Illustrious, would sink capital ships while they rested in port.

In May 1941, the carrier HMS Ark Royal would launch the same types of outdated Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers used at Taranto against Bismarck, pride of the German fleet. In the dying embers of day, a Swordfish torpedo would jam Bismarck’s rudder, leaving her helpless and doomed on the open sea. All planes returned safely to Ark Royalin the growing darkness.

At the time, only three nations boasted operational aircraft carriers: Great Britain, the United States, and the Empire of Japan. The Japanese would apply the lessons learned from these British victories to make the aircraft carrier the centerpiece of their attack force. Instead of one carrier, they would employ six of the 10 they had against Pearl Harbor. The attacking squadron was supported by two battleships, three cruisers, and nine destroyers. By the end of 1941, the battleship, queen of the oceans just two years previously, would be relegated to a support role. There were many lessons to be learned, and the United States learned them well.

While the smoke still drifted over Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy brass began to realize how lucky they were that none of their aircraft carriers had been in port that day. In Tokyo, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the planner of the attack, worried that he had not destroyed America’s carriers. He knew how valuable this new class of ships had become. Japan, in fact, was in the process of building five more carriers and converting two large passenger ships to carriers.

Of America’s six fleet carriers (and one escort carrier), three were in the Pacific Ocean on December 7. One of them, Saratoga (CV-3), was taking aboard planes at San Diego. Her sister ship, Lexington (CV-2), commanded by Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, was leading an escort of three heavy cruisers and five destroyers from Pearl Harbor to deliver 18 Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bombers to Midway Island for the island’s defense.

The third carrier, Enterprise, had just delivered 12 F4F-3 Wildcat fighters and their pilots to Wake Island and was returning to Pearl. Had bad weather not delayed Enterprise on her homeward voyage, she, like the battleships, would have been caught in the carnage.

Just as important as the survival of the carriers for the Navy was the failure of the Japanese to destroy the fuel stocks and their storage tanks at Pearl Harbor. This allowed the remnants of the Pacific Fleet to engage in immediate and continuous operations, setting up the upcoming American offensives much sooner than they would have if the fuel oil and the holding tanks had been destroyed.

Still, by the end of that day of infamy, the three flattops in the Pacific and their escorts were all that remained between Japan and the West Coast of the United States. The next day, Saratoga hurriedly departed San Diego and rushed to Hawaii. Upon arrival, she was assigned the task of reinforcing Wake Island, which was threatened with invasion. Delays, setbacks, and indecision resulted in Wake’s loss to the enemy before Saratogaand her supporting squadron could arrive.

Returning to Pearl, Saratoga and the other two carriers were assigned to mundane patrol and escort duties. The inaction did not sit well with officers or crew. They wanted to fight. Fortunately, changes were afoot.

On December 16, Yorktown (CV-5), the sister ship of Enterprise, weighed anchor at Norfolk, Virginia, for the Pacific Ocean to reinforce the decimated Pacific Fleet. Yorktownhad previously been in the Pacific and had made the move with the fleet from San Diego to Pearl Harbor in 1940. With increased threats from German U-boats in the Atlantic, however, she was transferred there in April 1941. Now she was headed back to Pearl as fast as she could steam.

Prewar naval planners and architects had been directed to design the hulls of all capital ships so that they would be able to pass through the Panama Canal. While it limited the size of new ships because of the rigid width and length requirements of their hulls, it allowed the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets to be mutually supportive. Yorktown made the timesaving passage through the canal and arrived at San Diego Bay on December 30.

There, she became the flagship of Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher’s Task Force 17 (TF17). His command also included the destroyers Hughes, Sims, Russell, and Walke,as well as the heavy cruiser Louisville and the light cruiser St. Louis.

Meanwhile, in Washington, the axe fell on the prewar commanders in Hawaii. On December 17, in a shakeup of personnel, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Admiral Chester Nimitz commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, effective December 31. The beginning of offensive operations was starting to take shape.

Admiral Nimitz and his staff immediately began developing plans for going from defensive to offensive war. The emotional choice at home would be to reinforce or rescue General Douglas MacArthur’s stranded army in the besieged Philippines, but this could be disastrous. The Philippines were 4,500 miles from Hawaii, deep within Japanese-controlled waters. This would make any American relief effort easily surrounded, cut off, and destroyed. Nimitz had to strike in such a way that his invaluable carriers had an escape route. That meant that the Philippines could not be saved.

Nimitz’s orders from Washington were first and foremost to protect the shipping lanes from the United States to Australia. The greatest threat to this vital lifeline at this time was the Japanese-held islands in the Marshall and Gilbert groups of islets and atolls spread over hundreds of miles of ocean. But Nimitz needed to know what to expect on and around those islands, and he needed to know quickly.

To find out, he dispatched the submarine Dolphin (SS-169) to recon the Marshalls without delay. In compliance with his orders, Dolphin’s captain weighed anchor and left Pearl Harbor on Christmas Eve.

The Marshall Islands had been in Japanese hands since World War I when they were wrested from German control. The island group became part of the League of Nations mandate that awarded them to Japanese administration.

The Gilberts (now known as Kiribati), farther south and within striking distance of Fiji and Samoa, were occupied by the Japanese after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Several of the islands in these two groups were being fortified with naval and air assets. From there, the American lifeline to Australia (4,000 miles from Hawaii) would be threatened by long-range flying boats and by submarines that could refuel at these advanced bases, the easternmost outposts of the Japanese Empire.

Nimitz believed that a raid on these islands could materially slow the progress and offensive capability of the enemy and, at the same time, relieve some of the Japanese pressure on the Philippines and the East Indies. A successful raid would also reassure the American public that the Navy was hitting back. Some of his advisers were skeptical, not wanting to risk the valuable aircraft carriers.

One concern was the unknown location of Japanese carriers, which, if near the Marshalls and Gilberts, could seriously threaten the American carriers. Code breakers and intelligence analysts, however, were reasonably sure that the Japanese flattops were in the western Pacific, supporting their major offensives.

Fortunately for Nimitz, Enterprise put into Pearl Harbor on January 7. Advised of the plan, the commander of the Enterprise task force (TF8), Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, was enthusiastic, and with his confident bravado, blunted all objections. His military philosophy was, “Hit hard, hit fast, and hit often,” and that was just what he now proposed.

While these discussions were going on in Hawaii, the first task assigned to Fletcher and Yorktown in San Diego was to escort the troop ships carrying 5,000 men of the 8th Marine Regiment to American Samoa for garrison duty and jungle training. Nimitz and Halsey planned that the convoy would be met upon arrival by Enterprise.

While Yorktown and the slower transports were steaming toward Samoa, Nimitz developed plans to make a carrier strike against Japanese-occupied islands in the Marshall and Gilbert groups.

With Halsey in overall command, Enterprise (known as the “Big E” to her crew) would attack islands in the northern Marshalls, while Yorktown would hit the Gilberts and southern Marshalls. As part of the plan, Lexington was to make a third raid on Wake Island as a diversion, while Saratoga was to perform a defensive patrol west of Hawaii.

Ironically, this strategy had already been spelled out in prewar planning. Many scenarios involving potential allies and enemies had been considered. The plan, named Rainbow 5, called for raids against the Japanese-occupied Marshall Islands.

In this scenario, three aircraft carriers and supporting cruisers and destroyers would bombard Japanese installations in the Marshalls by air and sea then fall back on three waiting battleships for protection. Nimitz and Halsey now planned a version of Rainbow 5 without the battleships, which were no longer available.

On January 10, 1942, Enterprise began to fuel and provision for a long voyage. The work went on all night. She departed Pearl Harbor the next day with her Task Force (TF8), including the heavy cruisers Northampton, Salt Lake City,and Chester, along with their destroyer escorts.

Halsey wanted to add more punch to his air strike, so he ordered his screening cruisers to bombard some of the target islands—just as the Rainbow 5 plan envisioned it. This task fell to Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who was in command of the cruiser group.

No sooner had TF8 left Pearl Harbor for the rendezvous with Yorktown and TF17 than things began to go wrong. That night (January 11), Saratoga, while screening Hawaii, was struck by a single torpedo from the Japanese submarine I-6. Damage was serious enough that she had to withdraw to the West Coast for repairs and would be sidelined from the war for several months.

Then, while Lexington was steaming 2,000 miles toward Wake Island and her part in the upcoming raid, she received bad news. There was only one aging oiler available to refuel the carrier and her thirsty task force after the raid. Without refueling, the Lexington squadron could not make it back to Pearl Harbor.

The oiler assigned to Lexington was the old and slow Neches (AO-5), whose keel was originally laid down in 1919. Early on the morning of January 23, Neches, while steaming around the planned rendezvous point, was hit and sunk by two torpedoes from another Japanese submarine, I-72. Without access to fuel oil, Lexington had to bow out of her role in the coming offensive raid.

Before the raid even began, half of the Pacific’s Fleet carriers were out of action. But that did not deter the aggressive Halsey or the eager support of Admiral Nimitz. The raid was still on. On January 23, Yorktown and the troop transports arrived off of Samoa where Enterprise was waiting. The Marines with their artillery and equipment were safely disembarked, and by the 25th, the two carrier groups steamed northward together toward their twin objectives.

Both carriers had a decided advantage over most other U.S. Navy ships and all Japanese ships. They were among the very first American warships to be outfitted with radar. The Japanese would not have access to this technology until much later in the war, by which time it was too late to make a difference.

All ships of the two task forces were refueled at sea on January 28. Enterprise did not begin refueling until after dark, a process that would last for more than five hours. Nighttime refueling at sea was a new and dangerous venture at this point in the war, and it was not until later that frequent rehearsal would make it routine. On this night, however, it was an experiment of necessity. Arrangements were also made for the ships of both carrier groups to refuel once more after the raid before making the 2,250-mile run back to Pearl Harbor.

Halsey assigned Fletcher and TF17 the job of attacking the reported Japanese positions on Makin Island in the Gilbert group and Jaluit and Mili Atoll at the southern end of the Marshalls. Enterprise, meanwhile, would concentrate its air power on Wotje and Taroa in the Maloelap Atoll in the northern end of the Marshall Island chain (Taroa is not to be confused with the more famous island of Tarawa in the Gilbert group). On January 29, the two carrier squadrons parted company to carry out their assignments.

As Nimitz’s plans were being firmed up in January, a report came from the submarine Dolphin that there was a considerable Japanese build-up of both sea and air resources on the atoll of Kwajalein, which was about 150 miles west of Wotje. As a result of this new intelligence, Kwajalein could not be overlooked, as aircraft from there could be a significant threat to TF8. This additional island would, of necessity, also have to be targeted.

As for the Japanese, their main objectives in the war at this time were the stubbornly defended Philippines, the oil-rich East Indies, and the battle for strategic Singapore. With the American Pacific Fleet neutralized at Pearl Harbor, the Marshalls and Gilberts seemed to be a safe backwater in their war plans.

Although the island groups were the easternmost outposts of the empire, they were sparsely defended. Only some gunboats and a single light cruiser represented naval interests there. Air assets included 33 older, fixed-gear fighters (only one modern Zero fighter would be encountered), nine land-based, twin-engine bombers, and nine four-engine flying boats of the 24th Air Flotilla. Most of the assets of the 24th were based at Truk and recently conquered Rabaul. The exact composition of these forces was unknown to the Americans.

The air attack plans of the two U.S. carriers were coordinated so that the first wave of aircraft from both ships would arrive over their respective targets at the same time: 15 minutes before dawn on February 1, just seven weeks after the raid on Pearl Harbor.

After leaving Samoa, both carrier squadrons had search planes constantly in the air during daylight hours to spot any lurking enemy planes, ships, or submarines. Radar continued the surveillance at night. Radio silence was strictly enforced. Only daytime semaphore flags and signal lights at night offered inter-ship communication.

As Yorktown drew nearer to her assigned targets, her escorting destroyers were detached to form a scouting line in defense of the carrier. The cruisers maintained continuous, close-in screening of the flattop.

At 4:15 amon February 1, Yorktown began launching operations. Eleven Douglas Devastator torpedo bombers and 17 Dauntless dive bombers were hurled into the predawn skies. The first target was the island of Jaluit, from which the Japanese administered the Marshall Islands.

The approach was difficult. Darkness, high winds, and rain squalls hid the attacking planes from the ground but also from each other. By the time the island was reached and a gray dawn at last appeared, the wind-tossed planes had been scattered, and the military installations were “socked in” by storm clouds.

Coordinated attacks were impossible under these conditions. Each pilot did his best on his own. The pounding weather, darkness, and high fuel usage were responsible for six planes not returning to their carrier.

A major factor in the aircraft losses for both carriers was the lack of training in flying at night or in stormy weather. Pilots under the stress of their first combat missions became disoriented in the windy gloom.

As it was, little was done in the way of damage on the targeted islands, but the Japanese were totally shocked and terrified that they could be attacked so easily. On the other hand, Americans were delighted once the news reached home.

The weather was better over Makin Atoll, where two long-range, four-engine Kawasaki H6K seaplanes (Allied designation Mavis) were demolished while sitting on the water. A gunboat was also badly damaged, and as at Jaluit, Japanese nerves and confidence were severely strained. The third island, Mili Atoll, was found to be deserted, and pilots assigned to it had nothing to attack.

Enemy response was late and ineffective. Three H6K seaplanes, however, were able to take off from Jaluit when the raid was over. One of them spotted the destroyer Sims, which was searching for the crewmen of a ditched plane. The Mavis made a diving attack on Sims, but its stick of bombs landed harmlessly in the destroyer’s wake as the speeding ship tacked violently. Antiaircraft fire chased the plane into nearby clouds. (Sims would later be sunk at the Battle of the Coral Sea.)

The destroyers, now in harm’s way, called upon Yorktown for air support. Six rugged Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters of the carrier’s combat air patrol (CAP) were sent against the flying boats, but no contacts were made near the destroyers. Shortly after 1 pm, however, Yorktown’s radar (for the first time in combat) picked up an incoming plane. The Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters of the combat air patrol were vectored in that direction.

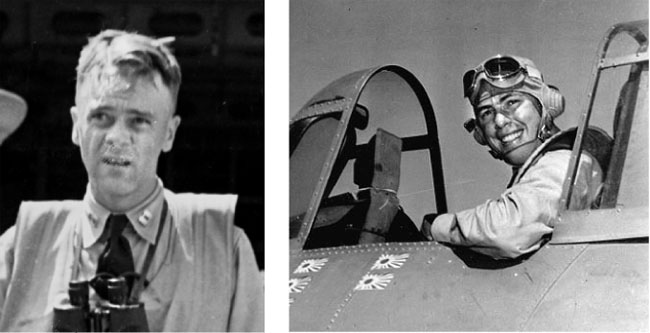

When the Mavis came out of the clouds, it was within 15,000 yards of the carrier. As the Kawasaki closed for an attack, it was set upon by Wildcats flown by Ensign E. Scott McCluskey and his wingman, Ensign John Adams.

One of them put a burst into the enemy’s wing root, causing it to explode in midair. On Yorktown, the open PA system allowed the relieved crew to hear the jubilant McCluskey exclaim over his intercom, “We just shot his ass off.” (McClusky would go on to score five victories at the Battle of Midway in a desperate effort to protect the ill-fated Yorktown.)

For the limited damage in the Gilberts, Yorktown lost seven planes and 16 aviators, mostly due to accidents. After his first round of attacks, Admiral Fletcher was prepared to move off to refuel and then renew the attack, but Halsey ordered him back to Pearl Harbor. Surprise in the hit-and-run attack had been achieved, and he did not want to risk defeat by an alerted enemy.

At the same time, Yorktown was launching its planes into the darkness, as was the distant Enterprise. In preparation for the raid, Halsey ordered every ship to be rigged for towing and being towed. If a ship was damaged, he wanted to be able to tow it to safety without losing time to do the preparation work under duress.

During the trip from Hawaii, the Wildcat pilots had talked the ship’s outfitters into installing steel plating from boilerplate behind their cockpit seats to protect against enemy machine guns. The steel added weight to the planes, but it would save lives.

When darkness settled in on the eve of the raid, TF8 made its final run to the target at 25-30 knots to arrive undetected at the launch point before dawn. When Enterprise arrived on station, she was 156 miles from Kwajalein, 106 miles from Taroa, and just 36 miles from Wotje. Like Yorktown, she turned into the wind for a 4:15 am launch time.

Six Wildcats were the first planes in the sky. They would serve as combat air patrol and would rotate with fresh fighters when low on fuel. This went on continuously until after sunset that day.

Next, dive bombers and torpedo planes (armed with three 500-pound bombs rather than a torpedo) roared aloft and buzzed toward distant Kwajalein Atoll. When they were away, more planes were launched toward Taroa and then Wotje. If all went well, the first wave of planes would arrive above all three island targets at roughly the same time, just before 7 am.

As with Yorktown, the pilots on Enterprise lacked practice in nighttime operations. Forming up in the darkness once airborne proved difficult, and at least one fighter was lost in the dark when it crashed into the sea.

During takeoff, Halsey anxiously watched the planes and their pilots from the admiral’s bridge. The man in overall command remained standing there, chain-smoking, drinking countless cups of coffee, and chewing his nails until the last plane was recovered in the afternoon. It was the kind of stress that would eventually result in a painful rash from shingles that sidelined him from the Battle of Midway.

While the flattop flung her planes into the darkness, Admiral Spruance led two of his cruisers, Northampton and Salt Lake City, close to Wotje Island for naval bombardment. Wotje was chosen for this special treatment partly because flying boats from there had assisted in the invasion of Wake Island. (A month later, on March 4, 1942, the only Japanese bombing of Oahu after the December 7 attack would come from two four-engine Kawanishi H8K Emily flying boats based at Wotje.)

The Japanese on Wotje were in for a pounding by air and sea. Meanwhile, Spruance sent Chester and two destroyers to supplement aerial bombing on Taroa as well.

As the American planes approached Kwajalein, the torpedo bombers peeled off from the formation of bombers and fighters to locate any ships within the shelter of the atoll. The dive bombers followed, looking for fortifications on the northern island of Roi, home of the atoll’s air base. The Japanese were alerted at the sound of incoming engines and rushed to antiaircraft guns as their fighter pilots desperately sought to get their planes off the ground.

Six SBDs made the initial attack, destroying the base radio station, at least one ammunition dump, and two small hangars. Four of the SBDs were shot down, but the Wildcats got the best of three Mitsubishi A5M Claude naval fighters with outdated fixed landing gear in the ensuing dogfights.

Meanwhile, the anchorage at Kwajalein was found to house several merchant ships, some submarines, and the light cruiser Katori, which had been stationed there even before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The initial attack caught the enemy by surprise. Little defensive fire rose up in the hazy dawn. Bombs damaged a merchant ship and sub-chaser. American pilots radioed Enterprise that they had found a “target-rich environment.” More planes were launched toward the anchorage.

Meanwhile, another bombing squadron found an unfinished airstrip on Wotje Island. The runway was pitted with bombs and the surrounding support buildings were shot up, but there were few assets there to target.

On Taroa Island, however, there was a bonanza of enemy aircraft. Taroa was the farthest east of all Japanese air bases and was close to being fully operational. It had active aircraft and two runways of more than a mile long.

Not expecting a major enemy base to be on the small island, only five Wildcat fighters (a sixth, mentioned above, was lost on takeoff), each carrying twin 100-pound bombs, were dispatched in the first wave. The leading plane mistakenly dropped its bombs on the deserted island of Tjan, some 15 miles from Taroa. The blast alerted the defenders, who had time to begin defensive measures. Worse, Taroa was just over 100 miles distant from the exposed Enterprise.

The Wildcats dropped their remaining bombs and then began strafing buildings and planes on the ground. Damage was limited because the attackers were not equipped with incendiary rounds. Despite the fire from four .50 caliber guns on each plane, eight enemy fighters made it into the air, but three of the Claudes were shot down in the brief skirmish.

It was now in the most critical moment that a flaw in the F4F’s .50-caliber machine guns became evident. They were prone to jam, and jam they did. Weaponless, the Wildcats broke off the dogfight with the Claudes and ran for home. One returning plane suffered 30 holes and dents in the newly installed seat armor, which saved the pilot’s life. All five Wildcats returned to Enterprise.

By 7:15 am, the attacking American planes over Wotje broke off and flew back to the carrier. It was the sign for Admiral Spruance to unleash his cruisers. Northampton and Salt Lake City opened up with their 8-inch guns on the island facilities and some frantic Japanese merchantmen who were trying to escape the anchorage for the open ocean. (Northampton would be sunk in November 1942 at the Battle of Tassafaronga. Salt Lake City would survive the war and two nuclear bombs at Bikini Atoll before being sunk as a target hull in 1948.)

At Taroa, Chester and destroyers Balch and Maury approached within 10 miles and proceeded in line ahead at 20 knots with Balch in the lead. At 7:15 am, they opened up on the beehive that was now the fully awake enemy airfields. Vengeful and humiliated Japanese pilots turned their attention to the cruiser. Chester took one bomb hit on her well deck. Eight men were killed and 38 injured. Another wave of bombers targeted but missed her altogether. The near misses were enough to convince the cruiser to withdraw at speed. (Chester would survive the war and be sold for scrap in 1959.)

On Enterprise, returning pilots were debriefed. It became evident that Taroa needed more destructive attention. The remaining Wildcats were exempted because they were all now required to fly CAP and protect the all-important carrier. Nine Dauntless torpedo bombers, this time armed with torpedoes, were on their way to Kwajalein to deal with shipping there. They were not equipped to deal with the aircraft at Taroa and so were not ordered to that island. Fortunately, there were others.

After 35 minutes of refueling and rearming, nine SBDs were launched against Taroa at 9:35 am. When this second wave reached the island, most of the Japanese planes were on the ground refueling and rearming. The incoming pilots could not ascertain any damage from the first raid. The diving attack came out of the sun from 13,000 feet and damaged or destroyed two brand-new, uncamouflaged hangars and some other buildings thought to be barracks or administration huts. Other bombs incinerated nine planes on the ground. A few Claudes tried to engage the invaders but were brushed aside. All nine SBDs returned home, but no one could yet rest.

All the while, Enterprise maneuvered to catch and launch her planes, sometimes coming within sight of Wotje Island. During the raid, the Big E launched planes a total of 21 times, requiring a turn into the prevailing wind each time.

Again, planes were hurriedly refueled and rearmed for a third strike at Taroa at 10:15. The rearmed and refueled SBDs again flew into the wind and disappeared over the horizon to appear again over Taroa. This time, enemy fighters were waiting for them, and antiaircraft fire erupted immediately when the SBDs came within range. Fuel tanks, the radio station, and other Japanese assets were set ablaze. The enraged enemy pilots were relentless and downed one plane for the loss of two of their own. The SBDs did not seek out combat, but fired defensively before racing into the clouds that were 2,000-4,000 feet above the island. Only one modern Zero fighter was spotted, but no one engaged it.

When Enterprise had recovered all of her planes, including those on a second strike to Wotje, Admiral Halsey ordered all of his ships to make a hasty retreat. The Japanese had focused on the incoming planes and the bombarding cruiser Chester. Halsey did not want to press his luck: the raid had been a hit-and-run attack, and it was time to run. Task Force 8 headed on a northerly course at full speed, 30 knots. The sailors and airmen, exhausted by their labors but exultant in their victory, liked to call these rapid withdrawals after a raid “Hauling ass with Halsey!”

As they raced to safety, radar picked up incoming aircraft at 1:30 pm. They turned out to be five Mitsubishi G3M, Type 96, twin-engine bombers, which the Allies called Nell. Each Nell was loaded with three 132-pound bombs.

Somehow, they had armed and taken off from the smoking wreckage of Taroa airfield, intent on doing the same to the Big E. Four of the CAP fighters were vectored to intercept them. Once again the jamming problem that plagued the Wildcat’s .50-caliber guns was visited upon the American defenders, and the Nells slipped into the safety of a scud of nearby clouds.

When the Nells came out of the clouds, they were only 3,500 yards off Enterprise’s starboard bow. Every ship’s gun that could be brought to bear engulfed the attackers in a torrent of lead. The ship’s captain, George Murray, a naval aviator since 1915, ordered a hard turn to port followed by a hard turn to starboard. The wriggling carrier and the wall of lead threw off the bombers’ aim, causing all of the bombs to fall into the sea and explode. Damage was confined to a single gasoline hose, which burst, caught fire, and fatally burned a crewman.

Four of the bombers turned impotently for home. The fifth Nell, piloted by Lieutenant Kazuo Nakai, trailed smoke and was too damaged for the flight home. Instead, Nakai determined to crash his plane into the carrier.

A hail of bullets and shells marked his approach. Then a crew member on the carrier leaped into action. Aviation Machinist Mate 3rd Class Bruno Gaido left his watch station and jumped into the rear gunner’s seat of a Dauntless dive bomber. This was Gaido’s station when the plane was in the air, but not when it was on deck. He fired off the plane’s twin .30-caliber rear guns at the incoming suicide bomber.

At the last moment, an alert Captain Murray ordered another hard starboard swivel. The combination of the hard turn and Gaido’s shooting point-blank into the cockpit of the incoming plane caused the death-bent bomber to miss the deck and fall into the sea. Its wing, however, clipped and severed the tail of Gaido’s SBD, which was parked on the edge of the flight deck.

The plane spun around but remained on deck. Gaido calmly climbed out of the ruined plane and helped put out a small fire from the near miss before disappearing below decks. He was afraid he would be punished for leaving his assigned post.

From the admiral’s bridge, Halsey had seen the whole thing and ordered that whoever it was in the rear gunner’s seat be brought to him on the bridge. When Gaido nervously appeared before his admiral, Halsey asked, “What is your rank son?” Gaido answered, “AMM 3rd Class, sir.” Halsey, beaming with pride, replied, “Well, you are AMM 1st Class, now,” and he promoted him on the spot.

There is a sad postscript to Gaido’s heroism. At the Battle of Midway, his SBD crash-landed into the sea, riddled with bullet holes. He and his pilot, Ensign Frank W. O’Flaherty, were picked up by the Japanese destroyer Makigumo and interrogated. Frustrated by the Americans’ unwillingness to divulge information and the humiliating loss of their carriers, their captors threw the two airmen into the vast, empty ocean, where they drowned. Their fate was not learned until the end of the war.

After the near miss from the Nells, the Big E and her task force continued their northward flight. Halsey figured that the Japanese would look for the raiders in the direction of Hawaii, so he steamed on this course until dark. It all played out as originally planned in Rainbow 5, except there were no battleships to fall back on.

The enemy was not yet done. A seaplane stalked the task force at a distance until the CAP fighters were able to force it into the sea. Then, at 3 pm, two more Nells made a bombing run at Enterprise. Again, heavy fire and nimble maneuvering resulted in near misses for the attacking bombers. The CAP fighters shot down one of the attackers and left the other trailing smoke on its homeward flight.

After dark, but under a full moon, Halsey retrieved his CAP fighters and maneuvered to the northwest until he found low-hanging clouds to hide under. After a few hours with no radar sightings, he finally turned for home.

After refueling, TF8 arrived at Pearl Harbor on February 5. Yorktown and TF17 arrived the next day. Their exploits preceded them, filling hearts with pride. The crews of ships at anchor amid the wreckage of Battleship Row sounded their whistles, and sailors cheered the victorious raiders of both carriers and their escorts.

It was the first American offensive victory in the Pacific War and was trumpeted across the nation as long-sought good news. Inflated accounts of the damage done to the Japanese swelled with the telling. It would not be until after the war that more modest assessments would be realized.

In Japan, the raid came as both a shock and a cautionary tale. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack, had estimated that his navy would have six months after that attack to dominate a Pacific war unhindered. As it was, Japanese total domination had lasted less than two months. The raid did not slow the Japanese juggernaut in the Far East, but it did make clear to their naval planners that American aircraft carriers would have to be dealt with and soon.

The Marshalls-Gilberts raid was just the beginning. A more audacious raid was planned for February 20. This time, Lexington, with a strong escort of four cruisers and 10 destroyers, steamed far into enemy waters to bomb recently occupied Rabaul.

Unfortunately, the squadron was spotted while still 350 miles from its objective. Enemy bombers soon appeared over the closest of the ships. In a violent struggle, 18 Japanese planes were shot down for the loss of two of Lexington’s fighters. No bomb hits were made on the carrier but several came near. It was a close call. Rather than press their attack on Rabaul or press their luck, the Americans withdrew.

Following his successful raid on the Marshalls, Admiral Halsey was directed to conduct a raid on Wake Island. Enterprise was to be supported by two cruisers and seven destroyers. Yorktown was also to participate, but was diverted for another task, forcing Halsey to proceed without her. Northampton, Salt Lake City, Balch, and Maury, all veterans of the bombardment of Wotje and Taroa, were to bombard Peale Island, a part of the Wake Atoll.

Halsey’s squadron arrived on station before dawn on February 24. Due to bad weather, the launch of planes was delayed so that the shore bombardment by the cruisers and destroyers occurred before the carrier planes could arrive. Fortunately, the Americans met with almost no fighter or bomber opposition.

A great deal of damage was done to Japanese installations for the loss of only three planes, two due to accidents and one to sporadic antiaircraft fire. No ships were hit. The raid was considered a success, and another one was planned.

This time, the target was the Japanese-held Minami-Tori-shima Island, known in the West as Marcus Island. This spot of land was 600 miles northwest of Wake and that much closer to the Japanese homeland. This time, only Northampton and Salt Lake City accompanied Enterprise.

During a full moon before dawn, Enterprise launched her planes only 125 miles from the island. Again, the SBDs carried 100- and 500-pound bombs. With thick clouds obscuring the island, Enterprise’s radar operator vectored the planes to their target—a new tactic at the time. No enemy planes were spotted, and only one attacking plane was lost to antiaircraft fire. Once again, an audacious raid, regardless of the limited extent of damage, proved that aircraft carriers could strike at will anywhere in the Pacific.

Admiral Halsey’s next mission would be to escort Colonel Jimmy Doolittle on his raid against Tokyo. Japan’s response would be the attack on Midway, where they hoped to draw out the American carriers and sink them. Instead, the epic carrier battle of World War II would end by blunting Japanese striking capabilities and naval dominance beyond repair.

The slugfest of the two navies around Guadalcanal later in 1942 would find each side locked in a war of attrition from which neither side would flinch and each would inflict heavy punishment on the other.

Slowly, the American production miracle overwhelmed the Japanese, hastening its inevitable conclusion. The U.S. manufacturing juggernaut would produce 17 fleet carriers, nine light fleet carriers, and a staggering 78 escort carriers. The Japanese, under increasing pressure from a dominant enemy, could not keep up.