By Al Hemingway

An odd assortment of spies was recruited by British intelligence to fool the Nazis as to the exact time and location of the Normandy landings.

An egotistical Polish freedom fighter, a Serbian playboy, a bisexual Peruvian lady, a Spanish chicken farmer with a vivid imagination, a temperamental Russian-born French woman attached to her dog, and a German citizen who loved the English and fancied himself another Anthony Eden. On the surface, none of these individuals have anything in common. During World War II, however, they were all being used by British intelligence to convince the Germans that the invasion of France was not occurring in Normandy. The elaborate ruse took four years to carefully mold but, in the end, this unlikely group of secret agents pulled off the unthinkable—and in the process saved thousands of Allied lives on June 6, 1944.

An egotistical Polish freedom fighter, a Serbian playboy, a bisexual Peruvian lady, a Spanish chicken farmer with a vivid imagination, a temperamental Russian-born French woman attached to her dog, and a German citizen who loved the English and fancied himself another Anthony Eden. On the surface, none of these individuals have anything in common. During World War II, however, they were all being used by British intelligence to convince the Germans that the invasion of France was not occurring in Normandy. The elaborate ruse took four years to carefully mold but, in the end, this unlikely group of secret agents pulled off the unthinkable—and in the process saved thousands of Allied lives on June 6, 1944.

In his latest book, Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies (Crown Publishers, New York, 2012, 386 pp., photographs, bibliography, notes, $26.00, hardcover), author Ben Macintrye has written another master spy thriller, much in the vein of his previous book Operation Mincemeat. The story has a cast of characters straight out of a James Bond novel with one important difference: they are all real—and so are their clandestine activities.

Among the officials with the British Security Service, known as MI5, was a “genteel and soft-spoken intelligence officer” named Thomas “Tar” Argyll Robertson, who was the mastermind behind this intricate plot to fool the Abwehr, or German intelligence, that the Allies would attempt an amphibious landing at Pas de Calais, the shortest route across the English Channel from Great Britain to France, instead of Normandy, where the real invasion would materialize.

Among Robertson’s unlikely entourage of secret agents was Roman Czerniawski, a Polish patriot who was captured by the Nazis after his underground organization in France was betrayed. He offered his services to the Abwehr, traveled to England, and immediately went to the British who brought him into their ranks. Czerniawski had to be extremely careful because he knew the Nazis would murder his family if they found out he was a double agent. He was code-named Brutus. A Yugoslavian ladies man was another spy for the British. Dubbed Tricycle, Dusan “Dusko” Popov proved invaluable as he passed along misinformation to the Germans despite his penchant for women, booze, tailor-made suits, and monogrammed handkerchiefs, which he flagrantly billed to MI5. Elvira de la Fuente Chadoir, aka Bronx, a bored daughter of a Peruvian diplomat and millionaire, frequented the gambling casinos in England, where she usually lost, picking up male and female one-night stands in the process. It was her consuming boredom that attracted her to the role as a British spy, feeding false data to the Germans.

Hot-tempered and unpredictable agent Treasure, Lily Sergeyev, had relocated to Paris when she was a child and offered her services to the Abwehr early in the war. When she traveled to England, Sergeyev quickly switched sides. Emotionally attached to her terrier-poodle Babs, she almost informed on the British when MI5 officials did not allow her to carry Babs to England (they later claimed Babs was run over and killed by a car) because of strict English quarantine laws for animals. Rounding out the five was Juan Pujol Garcia, agent Garbo, who was originally recruited by the Germans in Lisbon. Garcia secretly built a ring of spies who delivered much information to Berlin. There was only one problem—it was all fictitious. Garcia continued his deception until war’s end and was even decorated with the Iron Cross, one of Germany’s highest awards.

Perhaps the biggest hero to emerge among the spy world was Johnny Jebsen, whose parents had emigrated from Denmark and owned a shipping company. Although German on the surface, Jebsen was a fervent anti-Nazi but became a spy for the Third Reich, making enormous profits along the way. Jebsen and Popov were close friends, and it was the flamboyant Serb who eventually convinced him to be a double agent. A chain smoker and heavy drinker, Jebsen had made numerous contacts in the Abwehr. Unfortunately, because of his money-making schemes and threats to flee Portugal, he was whisked away to Berlin, tortured by the Gestapo, and sent to a concentration camp. His whereabouts after the war were unknown. Many, including his wife, believed he survived, faked another identity, and moved to another country. Known as Artist to the British, Jebsen never broke under torture.

Macintrye has penned a real edge-of-the-seat thriller. Double Cross is an engrossing book filled with twists, strange characters, and sub-plots that, although all true, could have been conjured up in the fertile mind of a Hollywood screenwriter.

The Battle for Tinian: Vital Stepping Stone in America’s War Against Japan by Nathan N. Prefer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 238 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Battle for Tinian: Vital Stepping Stone in America’s War Against Japan by Nathan N. Prefer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 238 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

In the predawn hours of August 6, 1945, three U.S. Army Air Corps Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers took off from North Field on the island of Tinian in the Marianas group. One of the aircraft, Enola Gay, named after the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., was carrying a new and deadly weapon—the atomic bomb—to be dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in hopes of ending the war in the Pacific. The bombings of that city and Nagasaki three days later were successful.

Japan sued for peace, and the conflict was over. In July 1944, however, it was the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions who would have to wrestle these islands from a determined and fanatical enemy, paving the way for the heavy bombers to drop their bombs a year later.

With the end of the operation to capture nearby Saipan, both divisions were depleted of manpower and equipment but were ordered to take Tinian. Reinforcements were on the way, but would not arrive until after Jig Day on July 24. Also, a heated argument ensued as to what beaches the leathernecks should land on, the wide but heavily defended strip near Tinian town or the narrow beaches known as White 1 and 2.

The decision to disembark the troops on the White beaches caught the defenders completely off guard. For the next eight days, Marine rifleman, supported by artillery and tanks, battled the Japanese into a pocket of resistance on the southern tip of the island. By August 1, Tinian was declared secured, although hundreds more of the enemy would perish in the months ahead.

Because of the ease of the operation, the Tinian campaign has been largely ignored by many historians who have described it as “easy.” What made it relatively effortless, however, was the meticulous planning and the complete surprise when the Marines waded ashore where the Japanese did not expect them to land. Tinian was the last time the enemy would use defense at the water’s edge, as the bloody struggles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa would later illustrate. Nevertheless, however easy one might say Tinian was, it is sobering to walk among the graves of the 328 who paid the ultimate sacrifice—and who made it possible for Tibbets to fly his bomber from the runaway on that fateful morning in August to put an end to all the madness.

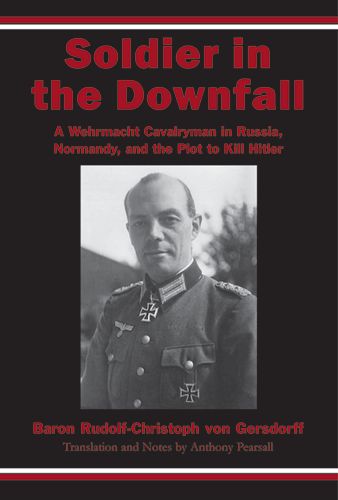

Soldier in the Downfall: A Wehrmacht Cavalryman in Russia, Normandy, and the Plot to Kill Hitler by Baron Rudolf-Christoph von Gersdorff, The Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA, 2012, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $22.95, softcover.

Soldier in the Downfall: A Wehrmacht Cavalryman in Russia, Normandy, and the Plot to Kill Hitler by Baron Rudolf-Christoph von Gersdorff, The Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA, 2012, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $22.95, softcover.

This is an intriguing behind-the-scenes look at the unsuccessful plots to assassinate Adolf Hitler as written by Maj. Gen. Baron Rudolf-Christoph Gersdorff, a member of the inner circle who conspired to eliminate the maniacal Nazi dictator and later managed to survive the Gestapo’s arrest, torture, and subsequent execution of suspected conspirators. Gersdorff, a man of integrity and honor, joined the ranks of the conspiracy because he was disgusted with Hitler’s management of the Army and, as he viewed it, the ruination of Germany.

There was more than one attempt on the German leader’s life. In early 1943, two bottles of cognac, each containing four clam magnetic mines, made their way aboard Hitler’s plane. Unfortunately, the fuse failed to work. In another attempt, Gersdorff tried to assassinate Hitler while he was touring an armory to look at captured Russian weapons. Carrying two explosive devices in his coat, Gersdorff would detonate the mines he was carrying, killing both Hitler and himself. Once again the plot failed because the fuses needed 10 to 15 minutes to work and a disinterested Hitler had quickly made his way through the exhibit and climbed atop a Russian tank located outside the building.

In July 1944, the bombing attempt at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair carried out by Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg was also botched when the briefcase carrying the bombs was moved. Although he was wounded in the blast, Hitler survived but several others were killed or maimed. The Gestapo immediately began a manhunt to nab all the conspirators.

Gersdorff expected to be arrested but it never occurred because Field Marshals Gunther von Kluge and Erich von Manstein never mentioned his role in the plot and Fabian von Schlabrendorff, who was tortured, as Gersdorff put it, “to the fourth degree,” never revealed his name.

Gersdorff would later be released from an Allied prison in 1947 and become involved with the Order of St. John and presented with the Grand Cross of Merit in 1979. He spent the last years of his life as a paraplegic, the result of injuries he sustained when falling from a horse.

As Gersdorff’s daughter writes in the introduction, “He saw loving his neighbor as his great task in life; both during the war, when he attempted to free the world from its biggest criminal, and after it, when he tried to help young people, to hear what they had to say, and (for the sake of their futures) to transmit genuine values to them, in keeping with his own passage through life.”

Special Forces Commander: The Life and Wars of Peter Wand-Tetley, OBE, MC, Commando, SAS, SOE & Paratrooper by Michael Scott, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2012, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Special Forces Commander: The Life and Wars of Peter Wand-Tetley, OBE, MC, Commando, SAS, SOE & Paratrooper by Michael Scott, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2012, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Born into a military family, Peter Wand-Tetley was destined to become a soldier—and what a soldier he was. Prior to the start of World War II, the elder Wand-Tetley, as well as Peter, traveled to Berlin for the 1936 Olympics. The younger Wand-Tetley had a chance to observe the Nazis, sitting just a few feet from Adolf Hitler, while a guest of the German government.

When war broke out in 1939, the younger Wand-Tetley found himself in an artillery unit but soon volunteered to join a commando outfit. After a verbal altercation with his father, who then reluctantly acquiesced to his son’s wishes, Wand-Tetley saw extensive action in North Africa and Crete where he parachuted behind enemy lines. It took nerve and courage to be a British commando—Hitler had ordered that if any were captured, they would be summarily executed.

Parachuting into Greece, he operated alongside Greek Resistance forces against the German occupiers and even assisted in the escape of 20 downed American aircrews. At war’s end, Wand-Tetley had been transferred to a parachute battalion and was sent to Java to put down a revolt by the Javanese against their colonial Dutch masters. Ironically, the Brits had to fight alongside Japanese troops in quelling the insurgency.

After the conflict, Wand-Tetley spent more than 30 years in the Colonial Administration Service serving in Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and the Caribbean. A humble person, he never kept a dairy highlighting his wartime experiences, a fact the author alludes to in the book. Nonetheless, Scott, a colonel in the British Army, has paid a great tribute to a fascinating individual, a larger-than-life character whose reputation as a leader will never be forgotten.

Short Bursts

The Inventor’s War: 1933-1947 The Durable Ideas and Innovations of World War Two by Craig Suter, Krieg Books, Tucson, AZ, 2012, 569 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, $39.95, softcover.

The Inventor’s War: 1933-1947 The Durable Ideas and Innovations of World War Two by Craig Suter, Krieg Books, Tucson, AZ, 2012, 569 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, $39.95, softcover.

Did you know that during World War II the herbicide Agent Orange was first used when Allied engineers were building the Burma Road in 1944-1945? That methadone was first used on German soldiers instead of morphine? That aluminum foil, duct tape, and the electric blanket were also invented? These and hundreds of other inventions and products emerged during the years prior to, during, and immediately following the conflict. The author has compiled hundreds of items that were born from the war effort with some remaining popular today such as nylon, television, and the electron microscope, to name just a few.

Other memorable products that Americans now take for granted include quick-change windshield wiper blades; automatic transmissions that were perfected and used in tanks and later automobiles; cruise control, which was invented to save gas that was rationed because of the large quantities being consumed overseas; paperback books because of their light weight; M&M candies, minute rice, and instant coffee. Kudos to the author for spending many hours amassing this collection of inventions that won a war and, ultimately, changed lives forever.

War Journey: Witness to the Last Campaign of World War II by William Dobbs, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2012, 164 pp., $36.95, hardcover.

War Journey: Witness to the Last Campaign of World War II by William Dobbs, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2012, 164 pp., $36.95, hardcover.

This book is poignant account of one soldier’s experiences in World War II while serving with the 206th Port Company of the 1st Engineer Special Amphibious Brigade. William Dobbs grew up in Georgia during the depths of the Great Depression. In addition to the financial hardships his family endured, he rarely saw his father. He never realized what became of him until he and his sisters discovered a letter written by their mother in 1971 but unread by the children until 1999. She bares her soul to her children and reveals that their father was an alcoholic and ran afoul of the law, escaping arrest by fleeing to Florida. Despite his flaws, Dobbs’s mother remained married to him.

Dobbs writes an interesting account about his time with his service unit, working feverishly to keep the frontline troops well supplied as they fought to take the island of Okinawa in 1945. Despite kamikazes and Japanese air raids, the 206th performed admirably. Dobbs remained in the Army and later the reserves, attending college and obtaining his medical degree as a psychiatrist. This is an absorbing and well-written story of one member of a unit that never received the recognition it so richly deserved.

The Fall of the Philippines, 1941-42 by Clayton Chun, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 96 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $19.95, softcover.

The Fall of the Philippines, 1941-42 by Clayton Chun, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 96 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $19.95, softcover.

Here is a great account dealing with the capitulation of the Philippine Islands in early 1942 and the lessons the United States learned from this humiliating defeat. The author explains that there was no clear command structure throughout the campaign. General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Thomas C. Hart squabbled over the best method of defending the islands and eventually set about formulating their own defensive plans. It was, as the author relates, “a point of major contention.” Also, the finger-pointing of where to place the blame when the Japanese struck at Clark Airfield, Iba, Nichols Field, and Del Carmon, destroying many of the B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and aircraft from the Far East Air Force, continues to this day among historians. In any case, without that valuable air support, the Allies were doomed.

As with every Osprey book, it comes complete with exceptionally detailed maps and excellent illustrations and photographs—a great book, especially for those just starting to learn about World War II.

Defending Fortress Europe: The War Dairy of the German 7th Army in Normandy, 6 June to 26 July 1944 edited by Mark J. Reardon, Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA, 2012, 344 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, softcover.

Defending Fortress Europe: The War Dairy of the German 7th Army in Normandy, 6 June to 26 July 1944 edited by Mark J. Reardon, Aberjona Press, Bedford, PA, 2012, 344 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, softcover.

The author, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who is a senior historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History, is quick to ask the question: Why another book on the Normandy invasion? What makes his so different is that it is one of the few written from the German perspective by using the actual war diary of a unit. The understrength German 7th Army had the important and unenviable assignment of defending the Atlantic Wall, a series of bunkers, pillboxes, and fortifications that stretched for miles along the French coast. The war diary of the unit has survived the conflict and serves as the primary source document to tell the opposing side’s point of view. Despite its efforts to stem the Allied tide, the 7th Army could not drive back the invasion forces because “the Germans were unable to shift forces to the most threatened point.”

The author has done a marvelous job of not overly editing the journal and occasionally inserts italicized remarks to clarify and explain certain passages from the diary.

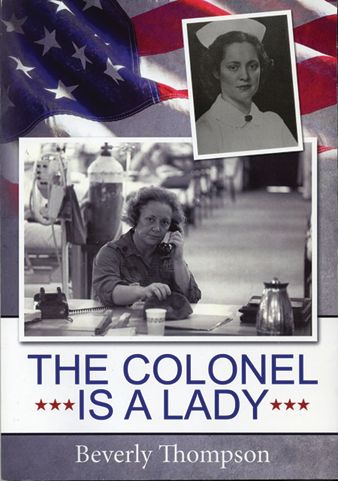

The Colonel Is a Lady: Le Grand Dame of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial by Beverly Thompson, CreateSpace, 2011, 181 pp., $10.00, paperback.

The Colonel Is a Lady: Le Grand Dame of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial by Beverly Thompson, CreateSpace, 2011, 181 pp., $10.00, paperback.

This is a moving story dealing with the life of Lt. Col. Evangeline P “Jamie” Jamison, a U.S. Army nurse who served her country during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Originally from Iowa, Jamie entered the service and was sent to New Guinea and the Philippines. It was here that she met Brad, an Army Air Corps aviator, with whom she fell in love. Jamie turned down his proposal of marriage and instead chose the Army as a career. It would be more than four decades later before they would be reunited. Jamison also played an instrumental role in the building of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington, D.C. Even at 92 years of age, Jamison remains active and, as the author writes, “To know Jamie is to love her.”

For more information on obtaining a copy of The Colonel Is a Lady, visit www.the colonelisalady.com.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments