By Hervie Haufler

“For several months after the outbreak of the war with Japan the very fate of our nation rested in the hands of a small group of very dedicated and highly devoted men working in the basement under the Administration Building in Pearl Harbor.”

That is how Admiral Chester Nimitz addressed the cryptographers who worked in what they called “The Dungeon” at the Oahu naval base. The admiral’s words expressed his gratitude to the group for breaking the Japanese naval code and, through their decrypts supplying him with detailed information concerning the Imperial Japanese Navy’s plans and intentions. Nimitz had used this information in creating his battle-winning strategies, particularly the great U.S. victory at Midway atoll.

Captain Forrest R. “Tex” Biard was one of that small group on the receiving end of the admiral’s tribute. He believes he is the last survivor.

Now, seated in his Dallas home in his 92nd year, Biard still does not have to fumble for a word in recollecting the varied roles he played in achieving Allied successes in the secret war of military intelligence—successes that gave Allied leaders the advantage they used in winning the larger conflict.

Biard recalls his father urging him to “make history” and, as the best way to do this, encouraging him to compete for an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. He took the tests, won out, and graduated in 1934, 24th in a class of 450.

While doing sea duty, he began to hear about a Navy program that sent officers to Japan for three years to familiarize themselves with the Japanese language and the mind-sets of the people, preparatory for serving in naval intelligence. He applied and was accepted. He was, however, a latecomer, arriving in Tokyo in July 1939. The result was that he and his group of nine other officer-linguists were able to complete only two years of their training before the pre-Pearl Harbor environment became too hostile to endure. In late August 1941, they received orders to leave immediately.

The Japanese, though, recognized the value of the officers’ experience to U.S. military intelligence and put roadblocks in the way of their departure. Biard is given credit for finally engineering their escape from Tokyo by making a deal that got them at last to Shanghai, China. From there they reached Honolulu. Biard and three of his associates reported to the Dungeon, where they became members of the Combat Intelligence Unit, more familiarly known as Station Hypo—the alphabetic equivalent of “H” in the international signal code.

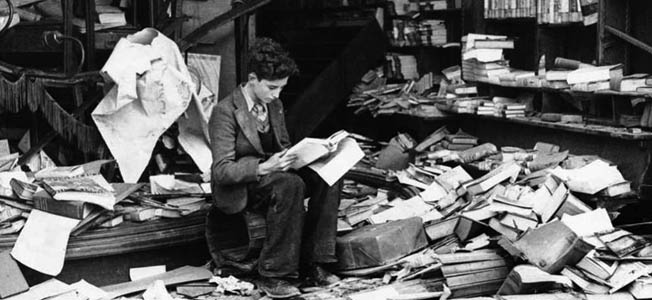

The newcomers were greeted by Hypo’s commander, Joseph Rochefort. “Gentlemen,” he told them, “here are your desks. Start breaking Japanese codes.” Biard felt himself very fortunate when he was given the desk next to Rochefort’s. He pitched in to learn from Rochefort, do what he could to help crack Japanese codes, and make up for lost time in improving his command of the Japanese language.

Here in the Dungeon, it was apparent that the work ethic was much more rigorously honored than elsewhere on Oahu. Even with the clouds of war thickening ominously, the prevailing attitude in Honolulu was one of slackness and indulgence. In the Dungeon, Rochefort set the example by never seeming to stop. He padded around in felt slippers and a red bathrobe, his way of surviving the chill of the Dungeon’s cold floors and bad air conditioning. The bathrobe’s pockets were always jammed with the message forms he had singled out for special attention. He frequently worked 20 hours out of 24.

Hypo was one of three Navy codebreaking centers carrying on the secret war against Japan. The others were “Cast” on Corregidor in the Philippines and the headquarters unit, OP-20-G, in Washington, D.C. To the officers of OP-20-G, control was important. They assigned the Japanese codes each unit worked on and decided what information to forward to their outlying posts.

Biard still rankles when he speaks of two critical mistakes he believes OP-20-G made in its relationship with Hypo.

The first was not forwarding information on the new breakthrough against Japanese codes achieved by the U.S. Army Signal Corps’ Signal Intelligence Service (SIS). This was the success that SIS, under the leadership of super-cryptanalyst William Friedman, had scored in breaking the code machine, code-named “Purple,“ used by Japanese diplomats and military attachés. The breadth of Purple’s use around the world would have produced information of great value both to Hypo and to Pearl Harbor’s commanders. The leaders at OP-20-G knew of the break but kept the information close to their vests. The Purple clone that was supposed to be assigned to the Hawaiian command was never sent.

The second and more important failure was OP-20-G’s decision not to have the Hawaiian station tackle the top code used by the Japanese Navy. Instead, Hypo was assigned three lesser codes, one of which was never broken because it was used so infrequently it never supplied analysts with enough material to get their teeth into.

In the days leading up to the Pearl Harbor attack, Biard and three others were sent to a nearby intercept station to conduct an around-the-clock listening effort. The purpose was to detect one of the “winds messages” which the Japanese were, it was thought, to insert in regular broadcasts of weather information as a warning to their embassies that relations with one or another foreign power were being broken off as a prelude to attack. The message that would designate the United States was “East wind rain.” Biard was on duty the December morning when he began hearing explosions. His first thought was that these were the sounds of routine blasting in the harbor. A look outside, though, revealed planes with red balls on their wings. The winds message had proved to be a vain hope. The attack was on.

Three days later, Hypo was turned loose on JN-25, the code most relied on by the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was a codebook code with a second super-encipherment. Biard watched admiringly as Joe Rochefort, with his deep knowledge of the Japanese language and ways of thinking, combined with an incredible memory, quickly began to make inroads into JN-25.

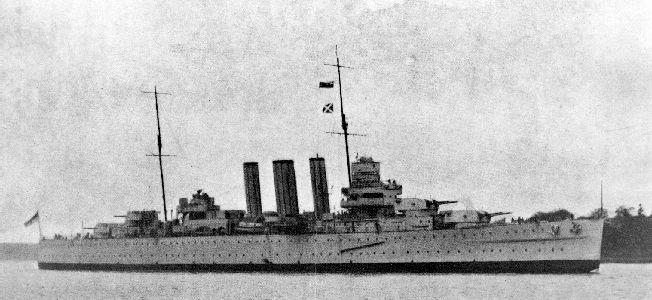

On February 14, 1942, Rochefort called Biard and Lieutenant Gilven Slonim to his desk. Hypo, he explained, was to supply officers to head up codework on each of two aircraft carriers that, with supporting ships, were to carry out sorties against the Japanese. One task force, grouped around the carrier Enterprise, would be under the command of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey. The second, with Yorktown at its center, would have Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher in charge. These two bold thrusts were U.S. attempts to counter the British loss of Singapore and stem the Japanese drive into Southeast Asia.

Rochefort handed Biard a coin. “All right, Tex, “ he said, “if it comes up heads you will go to Enterprise with Admiral Halsey. If it comes up tails, you go to Yorktown with Admiral Fletcher.”

Biard’s toss came up tails. It was his introduction to the Battle of the Coral Sea and to 101 days of difficulty and frustration under Fletcher.

Fletcher was one of those commanders, Biard recalls, who surround themselves with a staff of people they like, regardless of their competence. Since Biard had been chosen for him, not by him, Fletcher was antagonistic from the start. Their relationship quickly deteriorated. There came a day when the admiral, instead of lunching as usual with a few close cronies, invited his entire staff to his cabin. At the end of the meal, he looked toward Biard and said, “Biard, I want you to tell me and my staff all about your communications intelligence organization and the codebreaking it does.”

Biard was dumbfounded. Any well-informed commander would have known that military intelligence must be closely guarded, revealed only to those with a recognized need to know. Certainly this right did not extend to a large cabin full of uninitiated officers, not to mention the Guamanian and Filipino mess attendants present. Biard said he was sorry, but he was under orders not to disclose the nature of his work.

Fletcher erupted with rage. “You will tell me all I ask you and you will tell me now in front of my staff and anyone else present.”

Biard held his ground.

The result was that Fletcher, miffed, thereafter continued to ignore much of the increasingly valuable information that Biard and his two young radio intercept operators received and that Biard translated from the Japanese.

All of this internecine warfare came to a critical juncture in early May. Biard’s readings of Japanese messages told him that two strong Imperial Navy groups were bearing down from the east on Fletcher’s task force. Yorktown’s own protecting fleet had been weakened when Fletcher had ordered two Australian cruisers and their British admiral into positions well away from his own location. The reason for this move, Fletcher’s chief of staff whispered to Biard, was because, in the victorious aftermath of the coming battle, “he doesn’t want to hand out any medals to Britishers and Australians,” only to Americans.

Then came the morning of May 7. Biard knew from intercepts that the Japanese carriers were close enough that their planes could reach the Allied ships. Conversely, he was aware that if he could persuade Fletcher to launch his own planes, the U.S. task force would win “the coming battle hands down.” For half an hour, Biard says, he tried to convince Fletcher of the opportunity to surprise the Japanese fleet. More urgently, he warned of the danger of an oncoming assault.

“Young man, you don’t understand,” he quotes Fletcher as telling him. “I am going to attack them tomorrow.”

“But admiral,” Biard replied, “they are going to attack you today.”

The consequent mayhem has been described by Samuel Eliot Morison in his multivolume history of U.S. naval operations in the war, not as the Battle of the Coral Sea, but as “The Battle of Naval Errors.”

The carrier Lexington and other U.S. ships of Fletcher’s task force were sunk or damaged. Yorktown was crippled yet saved from complete destruction only by the violent evasive maneuvers managed by Captain Elliott Buckmaster. The Japanese also lost a light carrier, had a second badly damaged, and had to give up their immediate plans to establish a base in New Guinea for attacks on Australia.

Biard had the satisfaction, subsequently, of knowing that the Navy’s chief of staff, Admiral Ernest J. King, shared his low opinion of Fletcher. King insisted that Nimitz relieve Fletcher of his duties.

Meanwhile, back in the Coral Sea, Biard felt immense relief when Fletcher received orders from Nimitz to return under full steam to Pearl Harbor. Nimitz’s reason, Biard found out when he was welcomed back into the Dungeon, was that he needed every possible ship, including the battered Yorktown, to meet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s massive foray against Midway, which included a diversionary attack on American bases in the Aleutian Islands.

Yamamoto had organized his huge fleet for a surprise attack like his earlier one on Pearl. This time, though, it was Yamamoto who would be surprised. Rochefort and his team had broken JN-25 sufficiently to learn precisely where and when the attack would come. To side with his own codebreakers, Nimitz had had to go against the beliefs held by his higher command in Washington that the threat against Midway was only a ruse and that the real objective of the Japanese was either the U.S. West Coast or the Panama Canal. Deciding in favor of Rochefort and his team, Nimitz had sent only a ragtag fleet to counter the Japanese Navy’s subsidiary Aleutian offensive. He had positioned his main forces, including the hastily patched up Yorktown, but still only a David of a fleet, north of Midway so that it could fall on the flank of Yamamoto’s Goliath.

Biard found great tension in the Dungeon. The Japanese had planned twice to overhaul JN-25 but had been forced to delay the change because of difficulties in distributing the new codebooks. These delays had given Rochefort’s team the time with the old code to complete their revelation of Yamamoto’s plans. Now, on May 28, the Japanese did succeed in introducing a new code, and the Dungeon was shut out until Rochefort’s crew could begin breaking it.

There was nothing to do but wait, blinded, for a horrible seven days while the Midway drama played out. The Hypo crew knew it was altogether possible that in that time the Japanese could change their plans or even cancel them altogether. “In either case,” Biard recalls, “they would have made monkeys of us in the Dungeon and a martyr of Admiral Nimitz.”

The great moment came. On the morning of June 3, right on the predicted schedule, a patrol plane flying from Midway found the Japanese fleet just where it was supposed to be. Rochefort and his mates could relax and smile again, but they also prayed for the U.S. forces now in deadly battle.

“Our prayers there, too, were answered,” Biard remembers. All four Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk, and Yamamoto had to order a retreat back to home waters. The heretofore unrelenting Japanese offensive was broken; after Midway there was nothing but withdrawal and eventual defeat. As Winston Churchill wrote of the battle, “At one stroke the dominant position of Japan in the Pacific was reversed.”

Biard had one more codework adventure in the Pacific’s secret war. This came at the beginning of 1944 as the result of an incredible U.S. Army find in northern New Guinea. General Douglas MacArthur’s forces had been relentlessly driving back the Japanese armies there. A Japanese division had to withdraw too quickly to take all its codebooks with it. The remainder were dumped into a metal chest, which was sunk in a water-filled pit. U.S. Army engineers searching the area with metal detectors found the chest. When the codebooks were dried out back in Brisbane’s Central Bureau, they revealed all of the mainline Japanese Army code systems.

A serious bottleneck developed. There were not enough translators to handle the flood of decrypts. MacArthur appealed to Washington for help. By then the U.S. Army and Navy were working closely enough together that the Army answered MacArthur’s pleas by having two Navy linguists, Biard and Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Mackie, rushed to Brisbane to help.

On their first morning there, Biard recollects, they joined several Nisei translators working on the backlog. The Nisei, they found, were working their way up from the bottom of the high stack of decrypted messages. Instinctively, Mackie and Biard reversed the process, reaching for the freshest communiqué, the one on top of the heap. It was a momentous discovery. Translated, the 13-part message did nothing less than detail a conference of top-ranking Japanese Army and Navy officers at which the major decisions about the New Guinea front had been reached.

The reading of this message and of subsequent ones resulting from the captured codebooks supplied MacArthur with the information on which to base the deceptions that gave him victory at Hollandia in New Guinea and advanced the timetable of his return to the Philippines by months.

After the war, the Navy sent Tex Biard to Ohio State to acquire a master’s degree in nuclear physics. He was the operations officer during the first test of the hydrogen bomb. Retired from the Navy in 1955, he became a college physics professor for the next 23 years. Somewhere in Washington lies a recommendation that he receive the Distinguished Service Medal. An interviewer comes away from talks with him feeling that it would be hard to find anyone who deserves it more.

Hervie Haufler is the author of Codebreakers’ Victory, a review of Allied cryptanalytic successes in World War II published by Penguin’s New American Library. For research on this article, he wishes to acknowledge the special help of Captain Biard’s close friend, retired Navy Commander Jonathan M. Houp.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments