By Louis Ciotola

Peering out over the horizon, Austrian commander Prince Eugene of Savoy could see an army of Turks, the dreaded masters of southeastern Europe for the past three centuries, crossing the Tisza River near the town of Zenta on their way to pillage Transylvania. Although twice the size of the motley Imperialist force, the massive Turkish army was in a precarious position, dangerously divided on either side of the river. The Ottoman sultan, Mustapha II, had already crossed with half the army while the remainder, under the command of the grand vizier, Elmas Mohammed Pasha, stood idle, waiting to move.

It was a priceless opportunity for the young Austrian general to prove his mettle against a feared and vaunted foe. But just as Prince Eugene was about to pounce, a subordinate presented him with an unwelcome letter from Emperor Leopold I in Vienna. Eugene knew only too well what the letter contained. The emperor, fearful of risking his army against the more numerous Turks, had already urged Eugene on numerous occasions not to chance a battle with the Turks. Refusing even to open the letter, Eugene led his men toward the enemy. His bold if insubordinate decision would underscore the ascent of one empire and the concomitant decline of another.

Prince Eugene and the Resurgent Austrian Empire

The war between the Austrian Habsburgs and the Ottoman Turks was still in its infancy when the Turks besieged the Austrian capital of Vienna in July 1683. The city’s collapse would almost certainly have spelled the end of any Habsburg influence in the Balkans, if not the very dynasty itself. Fortunately for the Austrians, the commander in Vienna, Count Rudiger von Starhemberg, was as competent an officer as any in Europe. Starhemberg led a vigorous defense of the capital, aided in no small part by the arrival of a polyglot Christian army of Austrians, Bavarians, Saxons, various other Germans, and Poles. On September 12, 1683, the Austrians counterattacked the besiegers, routed the Turks, and saved Vienna. Present among the diverse heroes that day was a little-known 19-year-old Italian—Prince Eugene of Savoy.

Following the victory at Vienna, Leopold cast his eyes covetously over the Turks’ remaining European possessions and envisioned a new Hungarian empire under Austrian control. For the remainder of the decade, Leopold’s dream drew ever closer to realization. In September 1686, after a century and a half of Ottoman domination, the city of Buda fell to an Imperialist army under another hero of Vienna, Karl von Lothringen. Satisfied with their gains, the Habsburgs prepared to dictate peace to their enemies, but the stubborn Sultan Mehmed IV rejected such a distasteful idea. His obstinacy served to fuel the Imperialist war machine, and on August 12 of that same year the Austrians crushed the Turks on the battlefield of Mohacs, where centuries earlier the Ottomans had annihilated a Christian army and established their own dominance in the Balkans. This time, the shoe was on the other foot.

While the Battle of Mohacs fell short of crippling the sultan’s military might, it did lead to the Austrian capture of Transylvania. Two years later, on September 6, 1688, an Imperialist army under Bavarian commander Max Emanuel took a prized jewel in the Ottoman crown—Belgrade. Wounded in the effort was a still youthful Prince Eugene.

A Second Front Opens, Austria Loses Ground

Then Austrian progress ground to a halt. Following the fall of Belgrade, King Louis XIV of France announced a new war against the Habsburgs, in no small part due to his archenemy’s astounding success in the east. Leopold refused to back down from either challenge, throwing his kingdom into a war on two fronts. The strength of his forces in the Balkans suffered accordingly as troops were transferred to the Rhineland and Italy. The reduction of troops did not go unnoticed in the Turkish camp, and the sultan worked diligently to take full advantage of the weakened Imperialist army.

The capable Mustafa Koprulu was appointed grand vizier, and in 1690 a reconstructed army of 80,000 Turks under his command launched an offensive toward Belgrade. The depleted Imperialists had little choice but to fall back and abandon their hard-earned conquest, and by October the banner of the Ottoman Empire once again flew over the city. It was obvious that the Habsburgs had critically underestimated the strength of the Turks, but Leopold nevertheless remained undeterred. Still determined to establish a Hungarian empire, he reduced his battalions in the west and sent soldiers back to the eastern front. His moves resulted the following year in a victory at the Battle of Szlankamen, in which Koprulu was killed.

The momentum following Szlankamen could not be maintained, owing to growing financial stress and the war with France. By 1692, the Imperialist army again had ceased making progress in the field. A year later it failed miserably in an attempt to retake Belgrade. Increasingly desperate, Leopold looked for someone—anyone—to resurrect his fortunes. When the 25-year-old Elector of Saxony, Friederich Augustus I von Sachsen, offered reinforcements in exchange for overall command of the army, the emperor quickly accepted. It did not take long, however, for Augustus’s ineptness and lethargy to become apparent in the face of determined Turkish offensives on every front. Soon Leopold was looking for another savior. The solution to his problem was a young yet experienced foreign officer serving in Italy, Prince Eugene of Savoy.

Prince Eugene Ascends the Ranks

Eugene was born in Paris on October 18, 1663. Both his father, Prince Eugene Maurice of Savoy-Carignan, and his mother, Olympia, were of Italian origin. Following the death of his father and the exile of his mother, Eugene was left to the care of his grandmother. Desiring to distinguish himself, the young man sought a position in the French army, but Louis XIV rejected Eugene’s continued entreaties. Angry and disheartened, the prince looked to Austria, which had just begun its war against the Ottoman Turks. Spurred by news of the death of his brother, who had already been serving Emperor Leopold in Hungary, Eugene turned to his cousin, the Margrave Louis of Baden, for assistance. With Louis of Baden’s assistance, Eugene entered the Austrian ranks and went to war.

Events moved quickly for Eugene. Under his cousin’s command, he fought valiantly in the battle to relieve Vienna. News of his bravery spread all the way to the emperor, who was so impressed that he promised Eugene a regimental command. Rising in the Austrian ranks, Eugene again served admirably at the capture of Buda and led a cavalry brigade at the Battle of Mohacs. His efforts on the field earned him a promotion to lieutenant field marshal. Although he owed much to the emperor, Eugene’s growing knowledge, combined with his youth, caused him to question his master’s judgment. In 1688, when Leopold decided to continue hostilities with both France and the Ottoman Empire, the prince reacted sharply, writing: “Most people believe that we want to continue the two wars, although anyone with any senses who has the public good at heart is furious about it and knows that it is only monks who uphold this point of view.” Fortunately for Eugene, Leopold was unconcerned by such criticisms and continued to employ his youthful general. As it happened, he required Eugene’s talents elsewhere than the two primary war fronts. In 1689, along with many of his compatriots, Eugene was dispatched to the west, first serving briefly along the Rhine before heading to northern Italy. There he was to assist the Duke of Savoy and maintain a standing army of Spaniards. Before long, however, Eugene found the assignment distasteful. His deficient Spanish troops were unlikely to aid him in his martial ambitions, and Savoy was an uncommitted ally who was soon to defect from the Austrian cause. It would take a number of years and sustained setbacks in the east before Eugene would get the opportunity for independent command.

Eugene Assumes Command

Despite Augustus’s bungling, Leopold had little choice but to keep him on as the Imperialist commander in Hungary. With everything that was going wrong, he could not risk losing the Saxon reinforcements. The emperor was, however, willing to bring in an Austrian general to serve directly under Augustus as a means of obtaining at least some control over the situation. By late 1696, Eugene was practically begging to be transferred to the Hungarian front. Many in Vienna felt the same way. Foremost among them was the savior of the city, Rudiger von Starhemberg. Now serving as president of the War Council, the highest military rank in Austria, Starhemberg advised the emperor: “No one with more understanding, experience, application, and zeal for Your Imperial Majesty’s service, or with a more generous and disinterested temper, and possessing the esteem of his soldiers to a greater extent than the Prince” existed in the army. Starhemberg’s opinion was impossible to ignore. Before long, his insistence proved decisive. On April 5, 1697, Leopold dispatched Eugene to Hungary to serve under Augustus. He was 33 years old.

An amazing stroke of good luck came to Eugene soon after his arrival on the front. The recent death of the Polish monarch had left that kingdom’s crown vacant, and Augustus immediately began contemplating a bid to become the new king. He needed only to be urged slightly in that direction in order to be rid of him in Hungary for good. Leopold, Starhemberg, and Eugene were only too willing to oblige. Late that spring, Augustus made the decision to travel to Poland, where he would eventually be elected king. Eugene now had his first independent command.

Rejuvenating a Tattered Force

Although overjoyed at seeing Augustus depart, the emperor nevertheless retained doubts concerning Eugene’s youth and inexperience. He ordered Eugene to avoid all unnecessary risks, telling him “to act cautiously and avoid getting involved in any action without a good chance of success.” When Eugene joined the Imperialist camp outside of Kolluth in the middle of July, he found a fighting force all too willing to obey the emperor’s wishes. Augustus’s lethargy had caused the army to degenerate into an ill-led mob. Utterly lacking discipline and money, Eugene wrote to Leopold that he saw nothing more than “indescribable misery” among the men.

Eugene refused to allow such misery to dismay him. Upon reaching his destination, an officer informed him that the army was 31,142 strong. Eugene snapped back: “Thank you for the information. I am the 31,143rd, and we will soon be more. Let the enemy but allow me a few days in which to assemble Your Majesty’s soldiers and then, with God’s help, I will confound his purpose.” But the task ahead was a daunting one. Leopold had few resources with which to supply the army. Eugene would have to procure them himself. In doing so, the young general put on a display of logistical genius that few others could match. Using the rivers of the region to his full advantage, Eugene masterfully shipped in supplies from the surrounding countryside. Within a few weeks, the downtrodden Imperialist army was back on its feet.

A Daunting Foe

Fueled by French money, Eugene’s opponent, the 100,000-man Turkish army under the command of Sultan Mustapha II and his grand vizier, Elmas Mohammed Pasha, was determined to test its new opponent. On August 19, the lumbering Ottoman juggernaut crossed the Tisza River, intending to invest the Imperialist fortifications at Peterwardein. Initially, there was nothing Eugene could do to halt the enemy advance. His own army, although now better supplied, was still far inferior in size to the sultan’s force. But help was on the way. The timely arrival of reinforcements, troops who had just finished suppressing a revolt in Hungary, boosted his strength to 50,000 men. Still, with an army only half the size of the Turks’, an offensive was impossible. The alternative, a strategy long ago endorsed by both Leopold and Augustus, was to march to Peterwardein and prepare for a defensive struggle. If the Turks were to offer battle there, at least it would be on the Imperialists’ home ground.

Eugene’s arrival at Peterwardein changed everything. One look at the town’s defenses was enough to dissuade Mustapha from his original intent. Instead, he decided to march along the Tisza, choose a crossing point, and invade Transylvania to pillage for supplies. This complete alteration of tactics seemed to suggest that despite a tremendous advantage in men, the sultan for some reason was afraid to give battle. The updated situation encouraged Eugene to pursue a more aggressive strategy. Intelligence further revealed a sharp Turkish deficiency in cavalry and an over-abundance of raw recruits. Obviously, this was the reason the sultan shied away from a confrontation. With a newfound confidence, Eugene marched his army from the safety of Peterwardein in pursuit of the enemy.

Stalking the Enemy

The prince was not overconfident. After all, the sultan still possessed a formidable 2-to-1 advantage over him. Consequently, Eugene maintained a safe distance from the Ottomans, waiting for an opportunity to attack. Early on the morning of September 11, he received amazing news. A captured Turkish pasha named Cafer, at the threat of being “hacked to pieces,” informed Eugene that Mustapha’s army was in the process of crossing the Tisza near the small town of Zenta. Apparently only half the Turks had crossed the river; the others were still waiting on the near bank. The situation was perfect. Eugene would attack the divided enemy and drive it into the river. The prince quickly assembled his cavalry and raced toward Zenta, with the bulk of the Imperialist army following close behind.

The marshland that made up the terrain over which Eugene had to cross to reach Zenta failed to slow the determined commander. Within a couple of hours, the Imperialist cavalry was within striking distance of the Turkish army. The sight that greeted it was enticing indeed. The captured pasha’s information proved correct. The sultan, along with the bulk of his cavalry, artillery, and baggage, was already on the far side of the Tisza, having crossed over a hastily constructed pontoon bridge composed of 60 boats, while the grand vizier and most of the Turkish infantry, the janissaries, remained on the near side awaiting their turn.

Prince Eugene Ignores Leopold’s Orders

Eugene was so overjoyed by what he saw that for a moment he considered striking the janissaries at once with only his cavalry, but he wisely chose the safer course and waited for the arrival of his infantry. He did not, however, sit idle while he waited; he sent back orders to the approaching army to arrange itself for battle en route. Within hours the rest of the army arrived, and although it had force-marched for 10 hours and the day was growing late, the Imperialist soldiers were fully prepared to attack.

The weather was clear that afternoon, and the assembled Imperialists could easily discern the Turkish infantry massed on the flat ground waiting to cross the makeshift bridge over the Tisza. Although they had been eyeing the Imperialist cavalry for hours, the Turks were unconcerned. The sultan and his grand vizier never expected the Imperialists to be so bold as to attack their entire army. As a result, the Turkish soldiers prepared only slight earthworks and a ring of wagons to cover them as they forded the river. Only when the Imperialist infantry appeared did the Ottomans begin to brace for a possible assault. By then, it was already too late.

The Imperialist infantry arrived in a semicircle formation predesigned by Eugene to surround the Turkish bridgehead and crush it completely. There was no question in Eugene’s mind that he would launch an attack despite the growing lateness of the day. Such an opportunity could hardly be passed up. But just as he was about to give the order to advance, the prince received a letter from the emperor. Eugene knew the meaning of the correspondence. Leopold had been begging him to refrain from aggressive action ever since he sent the prince to Hungary. Eugene simply chose to ignore the letter, leaving it unopened. Nothing was going to stop his date with destiny.

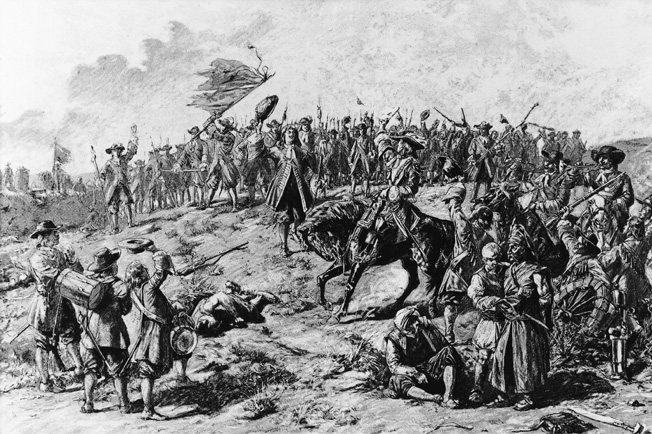

Eugene Instigates the Battle

Eugene ordered the army forward directly into the face of the enemy. The right wing was commanded by Siegbert Heister, the left was under Guido Starhemberg (no relation to the famous Rudiger), and Eugene himself was leading the center. In the late-afternoon sunlight, the Imperialist army moved forth.

The Turkish sultan unleashed his artillery against the advancing Imperialists from the opposite bank of the river, but his 100 guns were entirely ineffective, while the Austrian guns by comparison began mauling the enemy ranks. Within a short time, the Turks were becoming increasingly disorganized. In an attempt to slow Eugene’s progress, the grand vizier ordered what little cavalry he had available on his side of the river to charge. The assault failed miserably, driven off by the Austrian dragoons. Meanwhile, a mass of Turkish spahis was moving back across the bridge on orders from Mustapha to assist the grand vizier. The bridge being narrow, the pace of the horsemen was excruciatingly slow, and their presence clogged the only possible escape route for the surrounded janissaries. Should their line break, the Ottoman army would suffer an unimaginable catastrophe.

Eugene quickly recognized that the Turkish right was the key to winning the battle. To its rear, the waters of the Tisza were shallow due to a large sandbar. Eugene instructed Starhemberg and his left wing to wade through the waters, bypass the Turkish defenses, and hit the enemy from behind. The maneuver was an instant success, catching the defenders completely by surprise. Their attempts to turn and face the threat to their rear created utter confusion in the Turkish ranks. For Eugene, the time was ripe to launch an all-out assault. He gave the order for the right and center to advance simultaneously, personally leading the charge over the marshy ground. Only infantry could advance in such wet terrain, but that proved to be all the force the Imperialists needed.

Mustapha’s Janissaries are Cut Down

The turmoil behind the Turkish lines created panic and caused the soldiers to leave their earthworks and wagon barrier almost entirely defenseless. The Austrian attackers easily penetrated the abandoned defenses into the heart of the frantic mob that was once the proud Turkish army. The janissaries never even bothered to discharge their firearms, but rather reached immediately for their swords in a vain display of medieval bravery. With the spahis still bunched together on the bridge, there was little hope to escape. When Starhemberg’s men reached the bridge themselves, even that little glimmer of hope disappeared.

From Sultan Mustapha’s vantage point, the scene across the river was heartbreaking. The cream of his army was being cut to pieces in brutal hand-to-hand combat, and there was absolutely nothing he could do about it. Bottled up against the river, the Turks fought like madmen until Starhemberg ordered his troops to fire point-blank into their backs. The volley was punishing and its effect disastrous. Many of the Turkish soldiers now chose to risk the deeper flowing waters of the Tisza rather than face the cold steel and fury of the Imperialists. A mass flight ensued as thousands of Turks rushed into the river. The result was horrifying. The vast majority of the Turks, attempting desperately to swim over one another, thrashed and sank to a watery grave. Of the drowned a shocked Eugene would later comment, “Men could stand on the dead Turkish bodies as if on an island.” Barely 1,000 Turks reached the far shore alive.

Some, however, fought on, and the annihilation of the remaining janissaries was not complete until 10 pm. Only their pride kept these last valiant Turks fighting—by now, even their sultan was in the process of abandoning them, choosing to flee to Temesvar instead of making a stand with the remaining half of his army. The Imperialist troops, for their part, showed no mercy, prompting Eugene to comment, “The soldiers got worked up to such a pitch that they spared no one and butchered all who fell into their hands despite the large sums of money which the Pashas and Turkish leaders offered them to spare their lives.” When all was said and done, the riverbank was littered with the dead and dying in a volume as yet atypical in western warfare. Some 20,000 Turkish corpses littered the field of battle, with as many as 10,000 more drifting in the Tisza. Among them were the governors of Anatolia and Bosnia, four viziers, and the luckless grand vizier Elmas Mohammed Pasha. Rumor had it that many more Ottoman officers were murdered by their own furious men. The affair was brutally lopsided. Joining the dead were a mere 500 Imperialists, while another 2,000 were wounded.

Battlefield Victory, Strategic Stagnation

The next day the Imperialist army crossed the bridge into what had been Mustapha’s camp. There it discovered nothing short of a treasure. In his panic, the sultan had left behind all of his artillery, a huge sum in money, roughly 9,000 baggage carts, and an astounding 60,000 camels. The booty excited an already exultant Eugene even more. “Amongst the Turks there is a terrible confusion,” he reported. “With a little more preparation it would be possible to capture the entire kingdom and keep it.”

But Eugene was a naturally wise commander, and he soon came to his senses and adopted a more realistic approach. It was late in the year and a growing number of his men were becoming sick, a common problem during campaigns in the Balkans. Upon careful observation of the situation, Eugene complained of “six weeks in these wastes, where woods in particular cannot be found, where there is no forage and almost all the water has to be taken from stagnant pools.” There would be no pursuit of Mustapha.

Eugene’s spirits, however, were still high, and on September 15 he wrote an enthusiastic letter to the emperor, announcing his remarkable achievement at Zenta. “The great and signal victory and this considerable battle drew to a close with the day itself,” he wrote. “It was as though the sun decided not to set until it could see and cast its rays on the triumph of Your Majesty’s arms.” Only then, after the sun had set on that fateful day at Zenta, did Eugene finally open the letter from Leopold. The letter contained precisely what he had anticipated—an order to avoid battle with the Turkish army.

Eugene Takes Bosnia

Because of existing circumstances, Eugene decided to exploit Zenta with only a limited campaign into a now wide-open Bosnia. The offensive caught the Turks by surprise, and the Imperialists marched almost completely unmolested to Sarajevo. Upon reaching the city, Eugene dispatched two messengers to the Turkish garrison bearing his terms of surrender. The obstinate defenders fired upon them, killing one. Incensed, Eugene ordered Sarajevo set ablaze. This uncharacteristically brutal measure brought an end to the year’s fighting and put an emphatic stamp on what had been an utter disaster for the Ottoman Empire.

Achieving Imperial Ambitions

The Austrian commander returned to Vienna on November 17 to great applause. The city erupted in spontaneous celebration while the rest of Europe, with the notable exception of Louis XIV, cheered him as a Christian hero. To Emperor Leopold, Eugene personally presented an Ottoman seal found on the field of battle around the neck of the dead grand vizier. Contrary to rumors propagated by jealous rivals that claimed Leopold was angered by Eugene’s disobedience, the emperor was in fact overjoyed by his young protégé’s triumph. Instead of temporarily imprisoning the general, as the story went, the emperor showered him with praise and gifts. And why not? Eugene’s triumph had all but ensured Leopold’s long-standing dream of a Habsburg-dominated Hungary.

That dream became a reality two years later when an exhausted Ottoman Empire finally came to the peace table with Austria and its allies. On January 26, 1699, the Treaty of Karlowitz awarded the Habsburgs possession of both Hungary and Transylvania. Austria now ruled central Europe unchallenged and possessed a formal empire. The boundaries established at Karlowitz between Austria and the Ottoman Empire would last until the end of the World War I in 1918. In stark and unforgiving contrast, the Ottoman Empire began its unrelenting decline, a fall in fortunes that would one day cause it to be shamefully branded “the sick man of Europe.” From Vienna to Karlowitz, a span of just 17 years, the Turkish Empire went from its zenith to its lowest point. The Battle of Zenta was the final nail in the coffin.

New Beginnings for the Prince of Savoy

As for the hero of that battle, Prince Eugene of Savoy, his career had yet to blossom into its full glory. A year after the end of the Turkish war the calamitous War of the Spanish Succession began. The prince would have the opportunity to do battle as an independent commander against the very kingdom that had disowned him so many years before. Alongside the equally brilliant English general, John Churchill, first Duke of Marlborough, Eugene would win famous victory after famous victory against the French to become one of the premier military commanders in European history. And it had all started at Zenta, with an unopened letter from the emperor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments