By John Protasio

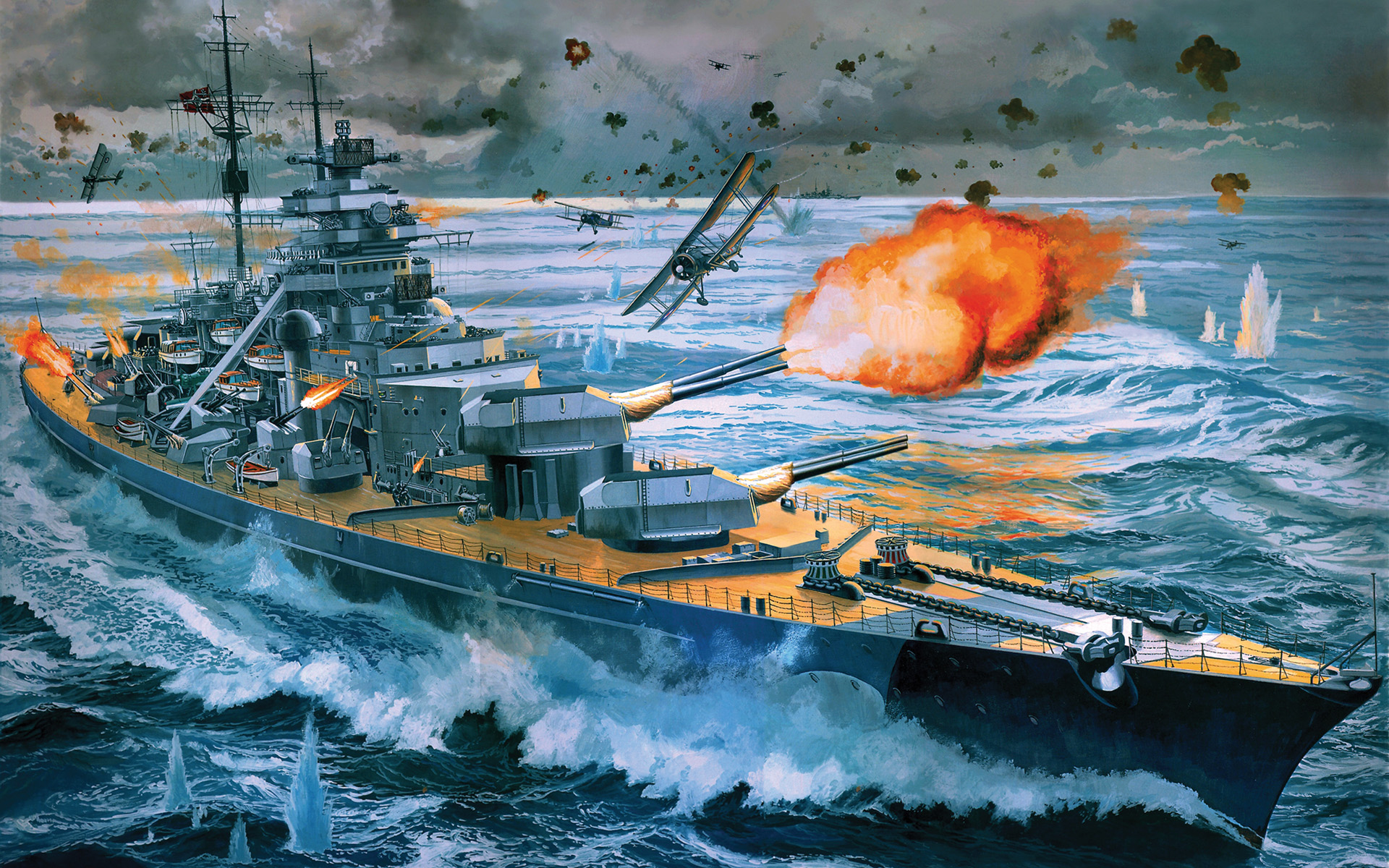

Baron Burkhard von Mullenheim-Rechberg’s life was in danger. An officer aboard the German battleship Bismarck, Mullenheim-Rechberg was at his station as his ship was trading salvos with several British warships. The young officer was able to make out two enemy battleships through his director. He felt his ship vibrate as she was hit by British shells.

The date was May 27, 1941. The place was the North Atlantic. Mullenheim-Rechberg’s ship was heading to St. Nazaire on the Atlantic coast for repairs. She was damaged earlier in a battle with British warships. At 8:30 am Mullenheim-Rechberg heard the alarm bells go off and rushed to his battle station along with hundreds of other sailors and officers.

At 9 am the battle had been raging for half an hour. Suddenly a shell landed near Mullenheim-Rechberg’s station. His director was shattered, and he was unable to locate the targets. Mullenheim-Rechberg and his men were lucky—if the shell landed a couple of meters lower they might very well have been killed.

Soon Mullenheim-Rechberg and his men were forced to abandon their stations. The German officer went near a gun turret where he found several men huddled together. “There’s still time,” he said. “We’re sinking slowly The sea is running high and we’ll have to swim a long time, so it’s best we jump as late as possible. I’ll tell you when.”

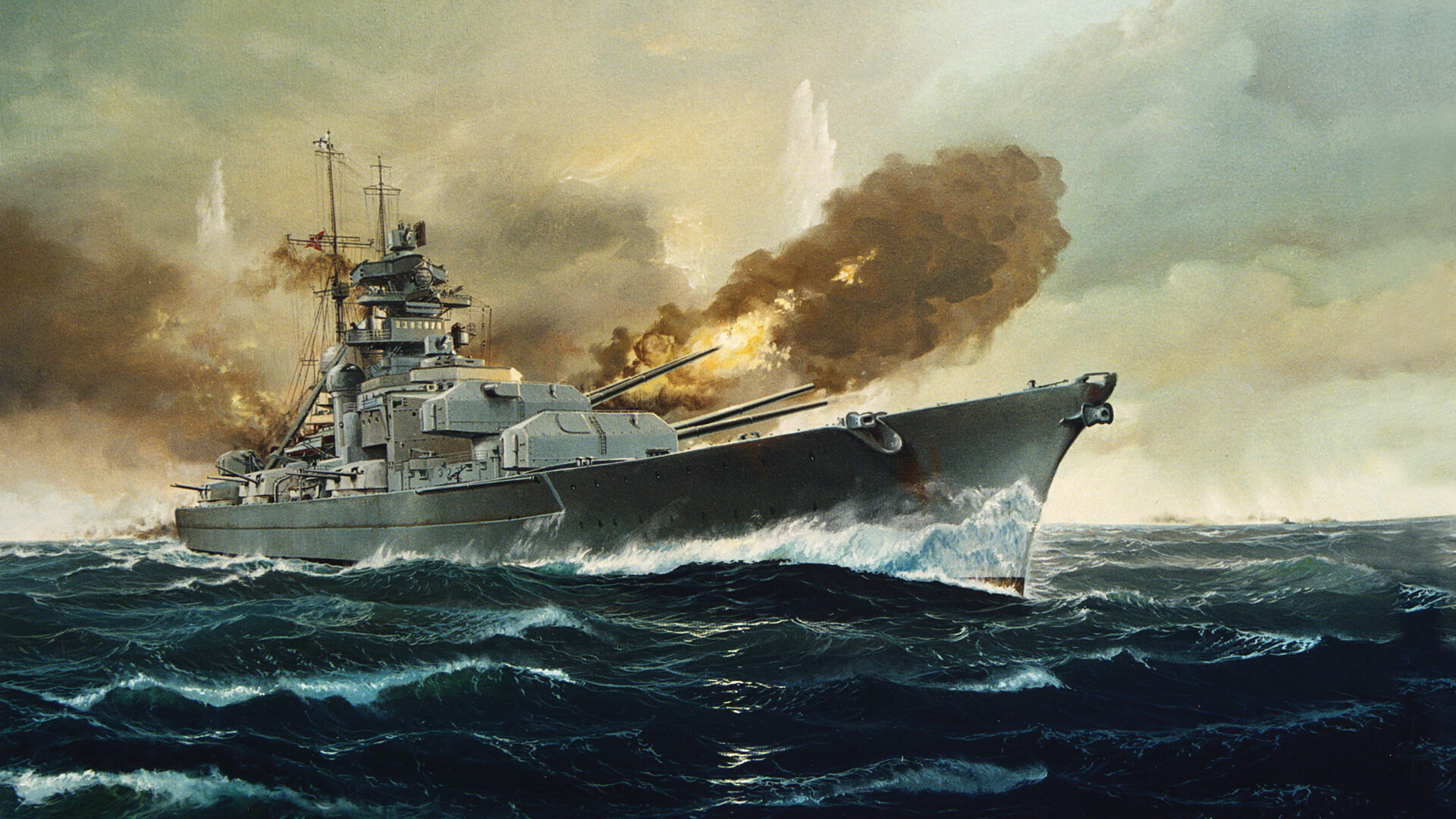

The vessel Mullenheim-Rechberg was about to abandon was Germany’s most powerful warship. Laid on July 1, 1936, and launched on February 14, 1939, the Bismarck joined the fleet in 1940. By this time World War II already had begun. When Kapitanleutant Mullenheim-Rechberg first saw her he was awed. “[I believed] she would be able to rise to any challenge, and that it would be a long time before she met her match,” he wrote.

The young officer had good reason to be impressed. The Bismarck measured more than 800 feet in length, displaced 45,950 metric tons, and had a full-load displacement of 50,955.7 tons. In some parts of the Bismarck, the armor ran 320mm thick. She was divided into 22 watertight compartments. Originally the Bismarck was intended to have 138 horsepower driving her at a speed of 29 knots, but this was increased to 150,000 horsepower, giving the warship a speed of a little over 30 knots.

The Bismarck had tremendous firepower. The main armament consisted of eight 38cm guns in four twin turrets, two fore and two aft. The secondary armament was 12 15cm guns in six double turrets. Taking into account of the possibility of aircraft attack, the Bismarck had several anti-aircraft guns ranging in size from 10.5cm to 3.7cm.

The standard crew numbered 103 officers and 1,962 enlisted men, but additional crew and non-combatants, such as war correspondents, for the pending mission totaled about 2,200 men. To lead these men, the German naval high command selected Captain Ernst Lindemann. Born in Altenkirchen in the Rhineland in 1894, Lindemann joined the Imperial German Navy in 1913. Because of his physical weakness, he was accepted on probation. Yet during his training Lindemann applied himself and was able to pass his early training. The following year he attended Murwik Naval School but the outbreak of World War I resulted in his not finishing his schooling; instead, Lindemann was given sea duty. After the war Lindemann immersed himself with the details of gunnery and became one of the best authorities on the subject in the German Navy. In the spring of 1940 he was given command of the Bismarck.

In May 1941 the German high command decided to dispatch the Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen to the Atlantic Ocean to raid Allied commerce. The fleet commander who was to lead these two vessels was Admiral Gunther Lutjens. At the age of 51, Lutjens had many years of experience. He joined the German Navy in 1907 and graduated 20th in his class of 160 cadets. Lutjens soon was given the responsibility to train officer cadets. During World War I he served in torpedo flotillas. By the end of that conflict he was commanding officer and half-flotilla leader of the Flanders Torpedo Boat Flotilla.

After the war Lutjens commanded torpedo flotillas and served on the Naval Staff. When World War II began he was vice admiral in charge of reconnaissance forces in the North Sea. During the invasion of Norway in April 1940 he led the covering naval forces. A few months later, Lutjens was promoted to admiral and given command of the fleet. During the late winter of 1941 he did significant damage to British shipping with his flagship Gneisenau and Scharnhorst.

The Bismarck departed from Gdynia on May 19, 1940, and was joined by Prinz Eugen, which had departed the previous day. The battleship and her companion arrived at Fjorangerfjord, Norway, where Lutjens received reports that German air reconnaissance detected no enemy ships in the area. This convinced the admiral that the British fleet was at anchor at Scapa Flow. Lutjens was also under the impression that it would be safe for him to go out through the Denmark Strait. Thus, he was more determined to carry out Exercise Rhine, which called for Bismarck to destroy Allied merchant ships.

Unfortunately for Lutjens and the Germans, British air reconnaissance spotted the Bismarck and her company. The pilots reported two large warships were escorting 11 merchant ships northward in the Kattegat. The intelligence was passed to Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet Sir John Tovey.

Tovey and his staff believed one of the large warships might be the Bismarck; if so, the other naval vessel probably was not a battleship for the battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst were known to be at Brest and Tirpitz was not ready for sea duty. Tovey concluded that the other ship must be either a pocket battleship or a Hipper-class cruiser.

The British admiral considered the enemy battleship’s intentions. It could be that the German warships were merely escorting the merchant ships to Norway, or that they were preparing to cover an invasion or attack on Iceland or the Faroe Islands, or that they intend to break out in the Atlantic and conduct commerce raids. He decided that the most likely of the more dangerous possibilities was that the two German battleships intended to escape into the North Atlantic to attack Allied shipping. He faced many problems. If one of the large enemy warships was the Bismarck, Tovey had only two battleships, his flagship, King George V, and the Prince of Wales, to deal with her. Also available were the battle cruisers Hood and Repulse and one aircraft carrier, the Victorious.

Tovey decided to split his forces up to watch all possible courses the Bismarck might take. The Hood, with Vice-Admiral L.E. Holland aboard, along with Prince of Wales, would patrol near the Denmark Strait. Tovey in his flagship King George V, Repulse, and Victorious would guard the passages from the Faroes southward. Tovey also ordered reconnaissance flights to confirm that the ship spotted in the Norwegian fjord was indeed the Bismarck. If so, the aircraft were to track her movements once she left harbor.

This last order was difficult because the weather was uncooperative. Yet on the afternoon of May 21, a pilot photographed what he took to be two cruisers in Grimstad Fiord just south of Bergen. Upon examining these photographs it was determined that one of the ships was the Bismarck.

Armed with this knowledge, Tovey was faced with a difficult decision. If he waited in harbor until the German battleship left Norway, he might miss an opportunity to sink her and she would be able to break away in the Atlantic. Yet if he set sail it might be days before the Bismarck departed. The British ships would exhaust their fuel and be forced to return to base, leaving the enemy an opportunity to escape. In the end the admiral decided to send Holland’s force out to sea; he would wait until he heard further reports. Further reports soon came in. Late in the afternoon of May 22, a British reconnaissance plane spotted Bismarck out of the harbor. That evening Tovey led his forces out to sea.

In the mistaken belief that the British warships were at Scapa Flow, Lutjens decided to pass through the Denmark Strait. He was ignorant of the fact that Holland was in the area and two cruisers, the Suffolk and the Norfolk, the latter of which was Rear-Admiral W.F. Wake-Walker’s flagship, also were covering the Denmark Strait.

During the evening of May 23, Captain R.M. Ellis was on the bridge of the Suffolk when he heard a seaman call out that there was a ship in sight. A few seconds later the seaman corrected his report to two ships. Ellis and the bridge crew rushed out and saw what they knew was the Bismarck and another warship.

Ellis realized his ship, a cruiser, was no match for a battleship such as Bismarck. Instead of attacking the enemy ship, Ellis’s duty was to shadow the battleship and report her movements to Tovey. The mist would hide him, but this meant keeping the enemy in sight would be difficult. Fortunately, his ship was equipped with a radar set, and therefore he could keep in contact with this device. Ellis sent a radio message informing his superiors that he had sighted the enemy. Meanwhile, Bismarck’s radar and hydrophones picked up the Suffolk. Lutjens gave the order to prepare to fire upon her.

An hour later the Norfolk came on the scene. Again Bismarck’s radar detected the presence of a ship. Lindemann informed the crew with the loud speakers, “Enemy in sight to port, our ship accepts battle.” The German battleship opened fire. The first few salvos resulted in straddles. Some splinters hit the Norfolk but the cruiser ducked into the fog. She then came out and along with Suffolk kept a discrete distance. The message, “Enemy cruisers are sticking to our course in order to maintain contact” was circulated to nearby British naval forces.

Word that the Bismarck and her companion were making for the Denmark Strait reached Holland aboard the Hood. He calculated where the enemy ships would be and turned his ships to that position. Holland increased speed to 27 knots. The admiral concluded he would make contact with the German ships at around 1:40 pm the following day. Holland ordered preparations for battle and hoisted his battle ensigns. However, it was not until shortly after 5 pm on May 24 that Holland’s lookouts spotted Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. Holland ordered his ships to close in on the enemy.

This would be one of the most dramatic naval encounters of the war. The greatest capital ships of both sides would square off. The Hood’s keel was laid down during the later part of World War I. She was not completed until after that war. This battle cruiser displaced 41,200 tons and had four screws. She had a speed of 32.1 knots and was armed with eight 15-inch guns. She was the pride of the Royal Navy.

Unfortunately for the British, the Hood had defects with her design. A battle cruiser, the ship did not have as thick or extensive armor as a battleship like the Bismarck. This would soon become evident.

Earlier Holland had sent his destroyers to the north in the event that the enemy might try to escape in that direction. These destroyers were still patrolling in the north when Bismarck was sighted. Why the admiral did not recall them when it became evident the German battleship did not alter course is not known. Perhaps Holland feared the enemy would turn to port when the Hood was sighted.

At 4:30 pm the crew of Prince of Wales prepared to launch a Supermarine Walrus airplane to conduct reconnaissance. Unfortunately for the crew, ocean spray had contaminated the airplane’s fuel. The crew was still trying to clear the fuel supply when it became evident that action would break out before they could launch the plane. Since the airplane posed a fire hazard, the crew jettisoned it.

Aboard the Bismarck, the lookouts spotted smoke to the south. Soon the British ships were sighted. The lookouts mistook them for heavy cruisers and Lutjens based his first few decisions at this time on this erroneous assumption.

When the British lookouts saw the enemy, men sprang to life. Orders were issued on both ships to prepare to fire. Holland knew Prince of Wales was not prepared to engage the enemy. One of her forward guns was defective and could only fire one salvo. It was Holland’s intention to close in on the enemy ships and then turn to open fire with their broadsides. Yet this meant that during the first few minutes of the battle the two British capital ships could bear only their forward guns on the German ships. They were to concentrate on Bismarck and leave Prinz Eugen to Suffolk and Norfolk.

As Hood and Prince of Wales closed in on the German warships, Lutjens now realized these ships were not cruisers but capital ships. He mistook the Prince of Wales for the King George V. Likewise, Holland erroneously thought the Prinz Eugen was the Bismarck. Holland was confused by the similarity of design and the distance between the ships.

Aboard Bismarck battle stations was sounded. Mullenheim-Rechberg reported to his station. Through his director he saw the British ships come into view. At 5:52 pm Hood opened fire. Prince of Wales, which was only a few hundred yards astern, likewise fired her enormous guns. Captain J.C. Leach of the Prince of Wales almost immediately realized that the ship the flagship was firing on was the wrong ship. Nelson, like Leach, disregarded his orders and focused on Bismarck.

The Bismarck’s guns remained silent at first. Mullenheim-Rechberg was in the after station wondering what was delaying the order to return fire. The ship’s first gunnery officer, Adalbert Schneider, asked by phone, “Request permission to fire.” He received no answer. He then said, “Enemy has opened fire.” “Enemy’s salvos well grouped.” He once more received no reply. Once again he asked, “Request permission to fire.”

For some unknown reason, Lutjens hesitated. Lindemann was frustrated. He was not about to let his ship be destroyed without engaging the enemy. “Permission to fire!” he repeated. Then, Bismarck opened fire on the Hood. Prinz Eugen likewise fired her guns. The latter hit the Hood, starting a fire on the battle cruiser. Hood’s gunners had difficulty seeing their target because of the ocean spray. The two British ships continued to close the gap between them and the enemy.

Bismarck’s first two salvos missed, although the second came close to the mark. At 5:55 pm Holland signaled Leach to turn to the port. As Hood turned she fired one last time. A split second later, the Bismarck’s fifth salvo hit the British battle cruiser. There was a great explosion and flames leaped from the Hood. Mullenheim-Rechberg heard someone shout, “She’s blowing up!”

“A colossal pillar of black smoke reaching into the sky,” Mullenheim-Rechberg later wrote. “Gradually, at the foot of the pillar, I made out the bow of the battle cruiser projecting upwards at an angle, a sure sign that she had broken in two.”

“‘Straddling!’ boomed out of Bismarck’s loudspeaker. In naval gunnery, when one round or salvo hits beyond the target, and the next falls short, the crew member observing the progress of the firing states that it is straddling. Bismarck’s crew was working as quickly as possible to get the target’s exact range. A hit was imminent.

“At first we could see nothing but what we saw moments later could not have been conjured up by even the wildest imagination,” said an observer in Bismarck’s charthouse. “Suddenly the Hood split in two, and thousands of tons of steel were hurled into the air…. Although the range was still about 18,000 meters, the fireball that developed where the Hood stood seemed near enough to touch. It was so close that I shut my eyes but curiosity made me open them again a second or two later. It was like being in a hurricane. Every nerve in my body felt the pressure of the explosions.”

There were few survivors. Ninety-four officers, including Holland, and 1,321 other crew members were lost. Only three men survived, Midshipman W.J. Dundas, Able Seaman R.E. Tilburn, and Ordinary Singalman A.E. Briggs. The Germans won this battle and expended only a few shells: 93 from Bismarck and 179 from Prinz Eugen.

The British tried to comprehend what exactly had happened to the Hood. Why did Holland try to close the range when his guns could almost reach as far as the Bismarck? Why did he keep the Prince of Wales so close to him? And why did the battle cruiser blow up?

The reason most likely will never be known because Holland was lost. However, Holland might have decided to close the range so that if he were hit it would be on the sides of the ship rather than on the deck where the armor was less thick. Also, he knew that the new Prince of Wales was not fully prepared for battle, and this may have affected his decisions.

There is the question of why Holland was not pointing end on to the Bismarck as he tried to close the range. In coming closer to the enemy he would be able to fire only half his guns until he turned to give a broadside. But by steering away from the line by 30 degrees, Holland was presenting an easier target as well as limiting his fire power. The most likely reason is that this tactic was taught to officers in the Royal Navy during this era, and the admiral was following his training.

It most likely will never be known what caused the explosion that doomed the Hood. Obviously, her magazine exploded. Some believe it was the fire caused by Prinz Eugen’s hit while others think it was Bismarck’s fifth salvo. Either is possible. Leading up to World War I, the British built their capital ships with thinner armor than their German counterparts. As a result, the British paid dearly for this at the Battle of Jutland. Construction of the Hood began before the British learned this lesson. There was talk of adding armor during the interwar years, but nothing came of this partly because of the disarmament atmosphere during the 1920s and early 1930s. By the time the war broke out, the British Admiralty needed all available ships and there was no time to improve her armor.

The fault does not lie with the crew of the doomed warship. Holland took, it can be argued, the rational course of action. The crew fought bravely. Mullenheim-Rechberg paid tribute to them. “I felt great respect for those men over there,” he wrote. According to some observers, there was a flash of orange coming from her forward guns a split second after she blew up. Hood was fighting gallantly to the end.

Leach of the Prince of Wales knew he could not fight the two enemy warships alone. Some of his guns were not operating and he had received no fewer than seven hits. Leach decided therefore to join Suffolk and Norfolk in shadowing Bismarck.

The Bismarck was also damaged in the battle. She was hit three times by the Prince of Wales. None of the crew was hurt, but some of the compartments were flooded and a few of the fuel tanks were damaged. The ship’s damage control crew went to work to effect repairs.

Lutjens was pleased with his ship’s performance. Yet, he concluded the damage done to Bismarck would interfere with her carrying out Exercise Rhine. The German admiral therefore decided to make for St. Nazaire for repairs. Many wondered why he did not return to Norway by way of the south coast of Iceland to Bergen, which was 1,100 nautical miles, or Trondheim, which was 1,300 nautical miles distant. Alternatively, Lutjens could have gone back through the Denmark Strait to Trondheim, a journey of about 1,400 nautical miles. The Denmark Strait had poor visibility but despite its typical bad weather the British cruisers were able to spot him and shadow his ship.

There was the possibility that since the British had spotted the battleship they might have brought up more forces in the Denmark Strait. Also, going to St. Nazaire meant a more southerly course and more hours of darkness. Lutjens had a better chance to shake of the cruisers shadowing him in the open sea. What is more, St. Nazaire had dry docks large enough for the Bismarck, and once repairs were completed it would be easier for the battleship to make for the North Atlantic to resume Exercise Rhine.

Lutjens knew that his ship was making two knots slower due to the damage from the battle. To make matters worse, Bismarck was leaking oil, which could give her whereabouts away.

A British plane had spotted the oil track and reported to the Admiralty that Bismarck was losing oil. But since this plane had been fired on by Bismarck’s antiaircraft guns, the Admiralty believed that the pilot was saying his plane was leaking oil. Soon, however, his superiors realized it was the enemy battleship that was losing oil. This tell-tale oil slick would help the British locate the Bismarck.

At 6:30 pm Bismarck disappeared in a fog bank. Ellis observed her with his radar and noticed that she had turned back and was heading straight for his ship. Fearing an attack, Ellis turned to the port and increased speed. When the range was down to 20,000 yards, Bismarck came out of the mist and fired on the Suffolk. Ellis put up a smoke screen and retreated, firing his guns at the same time. Prince of Wales opened up her guns in support of Suffolk. After a few salvos Bismarck broke off her attack and headed westward.

Lutjens signaled the Prinz Eugen, “Intend to break contact as follows: Bismarck will take a westerly course during a rain squall. Prinz Eugen will hold course and speed until forced to change or for three hours after separating from the Bismarck. Then [it is] released to fuel from Belchen and Lothringen, thereafter to conduct cruiser warfare. Execute on code word Hood.”

A few hours later Lutjens signaled, “Execute Hood.” Thus, Prinz Eugen left the Bismarck. She later reached Brest on June 1.

By this time, Tovey was concerned that Bismarck might escape. He decided to slow her down with an air attack launched from the aircraft carrier Victorious. He asked Captain Bovell of the carrier if he could do it. Bovell replied that he could if the enemy was within 100 miles of the Victorious, and at the moment it was not. Bovell calculated he would be within range at 9 pm. He had hoped that Victorious would continue to cut down on the range after her aircraft took off so that the pilots would have a shorter distance on their return.

Unfortunately for the British, Victorious was not within 100 miles of Bismarck at 9 pm. She was 120 miles away from the German battleship. To make matters worse, the weather was not cooperating. Yet Bovell felt he could not wait much longer. So he ordered nine Swordfish torpedo planes to take off to hunt for Bismarck.

The Swordfish planes, with the use of their aircraft-to-surface-vessel radar, spotted what they took to be the enemy. When they closed in they discovered it was their own ships that were shadowing the target. Norfolk guided them to the proper direction.

The planes picked up an object on their radars they believed was the enemy. The Swordfish planes broke cloud cover to attack, only to discover it was not Bismarck but the Coast Guard cutter Modoc from the neutral United States.

The planes regrouped and found the Bismarck. They dove and began the attack. The delay involving the Modoc gave the crew of the Bismarck time to man their antiaircraft guns. The pilots of the nine torpedo planes attacked with seeming disregard to their lives. “[It was] incredible how the pilots pressed their attack with suicidal courage, as if they did not expect ever again to see a carrier,” wrote Mullenheim-Rechberg.

Bismarck zigzagged to avoid the torpedoes but this was nearly impossible. The pilots dropped their torpedoes in several directions at the same time. Then there was an explosion. One of the torpedoes struck home. Mulelnheim-Rechberg looked at the speed and rudder-position indicators. To his relief the engines and rudder were intact.

The Swordfish planes then broke off their attack and returned to their carrier. Bismarck survived, owing largely to her thick armor belt, although one member of her crew was dead. The nine Swordfish managed to land safely on their carrier. Given that the pilots were new and the weather was bad, it was remarkable they all returned safely and even scored a hit.

The British ships continued to shadow Bismarck. Reports of U-boats nearby caused the Allied ships to zigzag. On the outward leg Suffolk lost radar contact with the enemy battleship but soon regained it on the inward leg. When the cruiser moved inward, they had lost the Bismarck.

Tovey found this bit of news discouraging. He decided therefore to have the aircraft carrier Ark Royal launch her planes in search of the rogue warship. Several land-based aircraft also joined in the search. Thus, the crew of the Ark Royal prepared to launch its planes. Unlike the pilots of the Victorious, these naval aviators were among the most experienced in the world. Yet there were still problems. The weather and sea states made launching the planes difficult. At one point, some of the planes rolled over and nearly fell overboard. But in the end numerous Swordfish became airborne.

By this time Tovey became fearful that Bismarck would escape. His ships were running low on fuel and he would soon have to recall them. Luckily for him, a Catalina from the coastal command reported sighting a battleship steering southeast by east and furnished its coordinates to the Admiralty. This was later confirmed to be the Bismarck.

The Ark Royal’s Swordfish quickly made for the scene, discovered a warship that they took to be the Bismarck, and attacked her.

But it was not Bismarck; it was the cruiser Sheffield of the Royal Navy. Her captain, realizing the pilots had made a mistake in identity, began to zigzag at top speed. Fortunately for him some of the torpedoes from the Swordfish had been armed with magnetic pistols (the device on a torpedo that detects its target by its magnetic field and triggers the fuse for detonation), which were defective and exploded upon hitting the water. Other torpedoes did not explode, and by skill and luck the Sheffield managed to avoid them.

Lutjens knew that the enemy was closing in on him. “We did not intend to fight enemy warships but to wage war against merchant shipping,” he told his crew. “Through treachery the enemy managed to find us in the Denmark Strait. We took up the fight. [You] have behaved magnificently. We shall win or die.”

The Swordfish planes of the Ark Royal flew a second sortie to redeem themselves. This time their torpedoes were armed with contact pistols. At around 8 pm on May 26 they came upon the Bismarck. This time they were sure it was Bismarck. As they attacked, the German warship opened up with her antiaircraft guns.

Aboard the Bismarck, Mullenheim-Rechberg heard an explosion aft. He became fearful as he glanced at the rudder indicator, which read “left 12 degrees.” He waited for it to change but it continued to read “left 12 degrees.” The young officer tried to cheer up his men at his station by saying, “We’ll just have to wait. The men below will do everything they can.”

But there was nothing the men below could do. Bismarck had been hit twice. One torpedo struck amidships but the armor belt protected the battleship from suffering much harm. But the other torpedo had struck aft and jammed the rudder hard to starboard. When reports came pouring in that the Bismarck was steaming erratically, Tovey could not believe his luck. He was about to withdraw his forces because of dwindling fuel. Now it seemed that he could sink the Bismarck after all.

By 10:30 pm, five British destroyers under the command of Captain Philip Vian came on the scene. Vian had intended to shadow the battleship and attack it if an opportunity arose. Unfortunately for Vian, the dark night and rough seas made launching a torpedo attack difficult. Nevertheless, Vian would make the attempt.

As the British destroyers came close, Bismarck opened fire. The darkness made firing difficult but by spotting them on radar she was able to come close to hitting the destroyers. During the night Vian’s ships fired a number of torpedoes at the Bismarck but it is believed none of them scored a hit. Vian then resumed shadowing the warship.

At 8:43 am on May 27, Tovey, in his flagship King Geroge V, and the battleship Rodney sighted the crippled German vessel. Tovey knew he had to act quickly because German war planes might soon arrive. Furthermore, there was the distinct possibility that enemy submarines might be rushing to the area. He quickly closed in on the Bismarck.

Four minutes later, Rodney opened fire. King George V soon joined in. Bismarck hesitated for a couple of minutes then returned fire. Her first salvo missed but the next salvo came much closer.

A few minutes later the Norfolk came within 20,000 yards and assisted Tovey with her 8-inch guns. During this time the Bismarck’s main fire control position was knocked out of action. From then on the German battleship’s fire became erratic.

Tovey turned to the south. A few minutes later the cruiser Dorsetshire arrived. She fired on the dying enemy vessel at the range of 20,000 yards. The range dropped to 12,000 yards and the Rodney employed her secondary armament.

By 10:00 am the Bismarck was still afloat, to Tovey’s surprise. He decided to fire on her at a reduced range. “Get closer, get closer,” he said. “I can’t see enough hits.” At that point, Rodney and Norfolk launched torpedoes, some of which hit Bismarck.

A short time later, Tovey decided he could not stay any longer. German planes and submarines might soon come to this area. Consequently, he ordered his ships to withdraw. Any vessels with torpedoes left were to fire them at the dying battleship. Dorsetshire fired two torpedoes, one of which exploded right under the bridge.

Aboard the Bismarck, Mullenheim-Rechberg was with crew near a turret. He decided to abandon ship. “It’s that time,” he told the men by the turret. “Inflate your life jackets, prepare to jump.” The men were about to jump when Mullenheim-Rechberg shouted, “A salute to our fallen comrades.” They all saluted the flag and then leaped overboard.

Slowly the Bismarck heeled over to the port and capsized. Then at 10:40 am on May 27, 1941, she sank. Like the Hood, the Bismarck, the pride of the German Navy, went down fighting gallantly.

In the water, Mullenheim-Rechberg was surprised the cold water did not disturb him greatly. He was troubled, however, by the scent of the fuel oil floating on the surface. The young officer was picked up by the Dorsetshire. In all, 110 men were picked up by British ships. The remaining 2,090 men on the Bismarck were lost, including Lindemann and Lutjens.

“The sinking of the Bismarck may have an effect on the war as a whole out of all proportion to the loss of the enemy of one battleship,” wrote Tovey. The destruction of this battleship was important for the British war effort. Britain already was suffering substantial shortages of food and war materials because German U-boats were sinking her merchant ships at an alarming rate. Had the Bismarck been able to escape into the North Atlantic, she and the Prinz Eugen might have wreaked havoc on convoys heading to the United Kingdom.

German naval personnel participating in Exercise Rhine performed bravely, but it takes more than courage to win a battle. Many Germans blamed Lutjens for not returning to Germany after sinking the Hood. However, his mission was to sink merchant ships and he may have believed he should carry out his orders. The German admiral may have believed that with the loss of the Hood there was no available enemy force sufficient to stop him from going to Brest or St. Nazaire for repairs. Lutjens ran the risk of air attack but he would also face this threat going back through the Denmark Strait or running down Norway going back to Germany.

One mistake the Germans made was to use their battleships piecemeal against Allied convoys. Perhaps instead of sending their battleships out alone or in pairs, they should have sent Bismarck, Scharhorst, Gneisenau, and Tirpitz (Tirpitz was ready for sea duty a few months after Bismarck was sunk) all in one group. It would have been difficult for the Royal Navy to deal with all four of them at once.

The naval campaign demonstrated the importance of air power in a modern naval battle. It was aircraft that first sighted the German battleship in anchorage in Norway and then later when she gave Suffolk the slip after the loss of the Hood. It was carrier-based planes that gave the Bismarck her fatal wound.

Although the future belonged to the aircraft carrier, there were some problems. The weather interfered with the air attacks delivered by the Victorious and Ark Royal. Also with her aircraft away on a sortie, the Ark Royal was vulnerable to an attack had the Prinz Eugen found her at this crucial time.

Although the era when battleships ruled the waves came to an end during this conflict, they were still important. Although ultimately the Swordfish planes inflicted the fatal wound, they would not have had the opportunity to do so had it not been for the damage done by the Prince of Wales. The hits from this warship damaged the Bismarck to the point that Lutjens decided to head for port for repairs. This brought the battleship within range of Ark Royal’s planes. Also, the hits from the Prince of Wales resulted in the oil leak that enabled the British to track their prey. Finally, it was Tovey’s battleships that reduced the magnificent German battleship to shambles.

The episode also revealed the importance of radar in modern war. Suffolk was able to shadow the Bismarck during much of this time with her radar. Bismarck was able to locate and fire on Vian’s destroyers

A key problem the British faced during their efforts to locate and destroy the Bismarck was fuel. Tovey’s ships were low on fuel and were about to turn back until they discovered the German battleship was steaming erratically due to the torpedo hit in her rudder. The Royal Navy at this time had not developed the ability to refuel at sea with tankers.

Thus ended the story of the Bismarck. The pursuit and destruction of the battleship was one of the most dramatic and important episodes of the World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments