By James Dunn

In the spring of 1916, as the result of intense international pressure, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer called in all his submarines after Germany announced an end to unrestricted underwater attacks on transatlantic merchant ships. With his subs idle, Scheer, the newly appointed commander of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s High Seas Fleet, had to come up with another plan for their use. He would send a portion of the fleet to attack a British port to draw out part of the Grand Fleet. Meanwhile, the submarines would lie in wait at the mouth of the Firth of Forth, Moray Firth, Scapa Flow, and other enemy naval bases to attack the British ships as they raced out to protect the homeland. German surface ships would then draw the enemy fleet farther away from the British mainland into the waiting range of the German fleet. If done properly, Scheer’s audacious plan could break the British North Sea blockade that slowly but surely was strangling Germany.

Mistakes on Both Sides

The plan was a good one, but there were multiple delays. Earlier damage to the 23,000-ton battle cruiser Seydlitz, armed with ten 11-inch guns, postponed the start of the operation. Captain Herman Bauer, commander of the U-boats, suggested that the submarines go out at the earliest moment for reconnaissance. Scheer agreed, sending the subs out in mid-May. This turned out to be a tactical error, since it took the U-boats out of the upcoming battle. Because of further delays, Seydlitz was not ready until May 29. By then, the submarines were low on fuel and Scheer’s ambitious plan had to be put into action quickly or else the window of opportunity would close. On that day, Scheer radioed his submarines with another change of plans. Instead of attacking a British coastal port, the Germans would scout for commercial ships around the Jutland peninsula of northern Denmark. There was a problem with the message—most of the German submarines did not hear it, but the men in Room 40 did. That was the top-secret room in the British Admiralty where cryptologists listened in on German radio signals and decoded their messages. The British knew exactly when the Germans had set sail, and Admiralty dispatched the entire Grand Fleet to attack them.

There was a blunder at the beginning on the British side, as well. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander in chief of the Grand Fleet, was told that Scheer was still in his base on the Jade River. Jellicoe assumed from the message that the entire German fleet would not be offering battle, and that Scheer would only venture out to cover Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper’s return. Since Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty, commander of the Battle Cruiser Squadron, was 70 miles farther out to sea and traveling a more southerly route than Jellicoe, this meant that Beatty most likely would engage the enemy first. Accordingly, Jellicoe proceeded at a leisurely 15 knots toward a rendezvous with Beatty, which was scheduled for around 1530 off the coast of Denmark. In the meantime, both Beatty’s and Hipper’s scouting ships spotted a Danish tramp steamer, N.J. Fjord, in the vicinity. The German ship Elbing sent two torpedo boats, B109 and B110, to investigate. At the same time, the British light cruisers Galatea and Phaeton broke off from Beatty’s force to get a better look at the lone steamer. Both pairs of scouts reported enemy ships on the horizon. At 1428, Galatea and Phaeton fired their 6-inch guns at the German torpedo boats, inaugurating the Battle of Jutland.

As soon as Beatty was told about the enemy ships, he turned south-southeast to meet them in battle. He wanted to get between the German line of ships and their home base near Horns Reef. As he turned to engage the enemy, Beatty had his flagman signal the change in direction. Owing to the distance between them, Rear Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas did not see the signals. Evan-Thomas commanded the 5th Battle Squadron, which included four 27,000-ton Queen Elizabeth-class dreadnoughts with eight 15-inch guns apiece. A devotee of Jellicoe’s who had been sent to Beatty’s command only 10 days earlier, Evan-Thomas was used to taking orders and following them faithfully and dutifully. He received the first message instructing him to turn north, but when Beatty changed course, his second signal was not received. Although Evan-Thomas could see the turn being made, he continued north until there was a distance of 10 miles between the ships, well out of range to assist in the opening of the battle. Instead of 10 British capital ships against five German ships, the battle would begin with a much more even 6-to-5 ratio.

The giant ships spent the first tense moments deploying into battle lines. Beatty had effectively cut off Hipper’s escape, and assuming that the rest of the German fleet was nowhere nearby, he was certain of victory. Hipper, in turn, steamed his ships south as though he were running away; instead, he was drawing Beatty into the trap set by the German High Seas Fleet—the same fleet the British thought was still sitting idly in the Jade River.

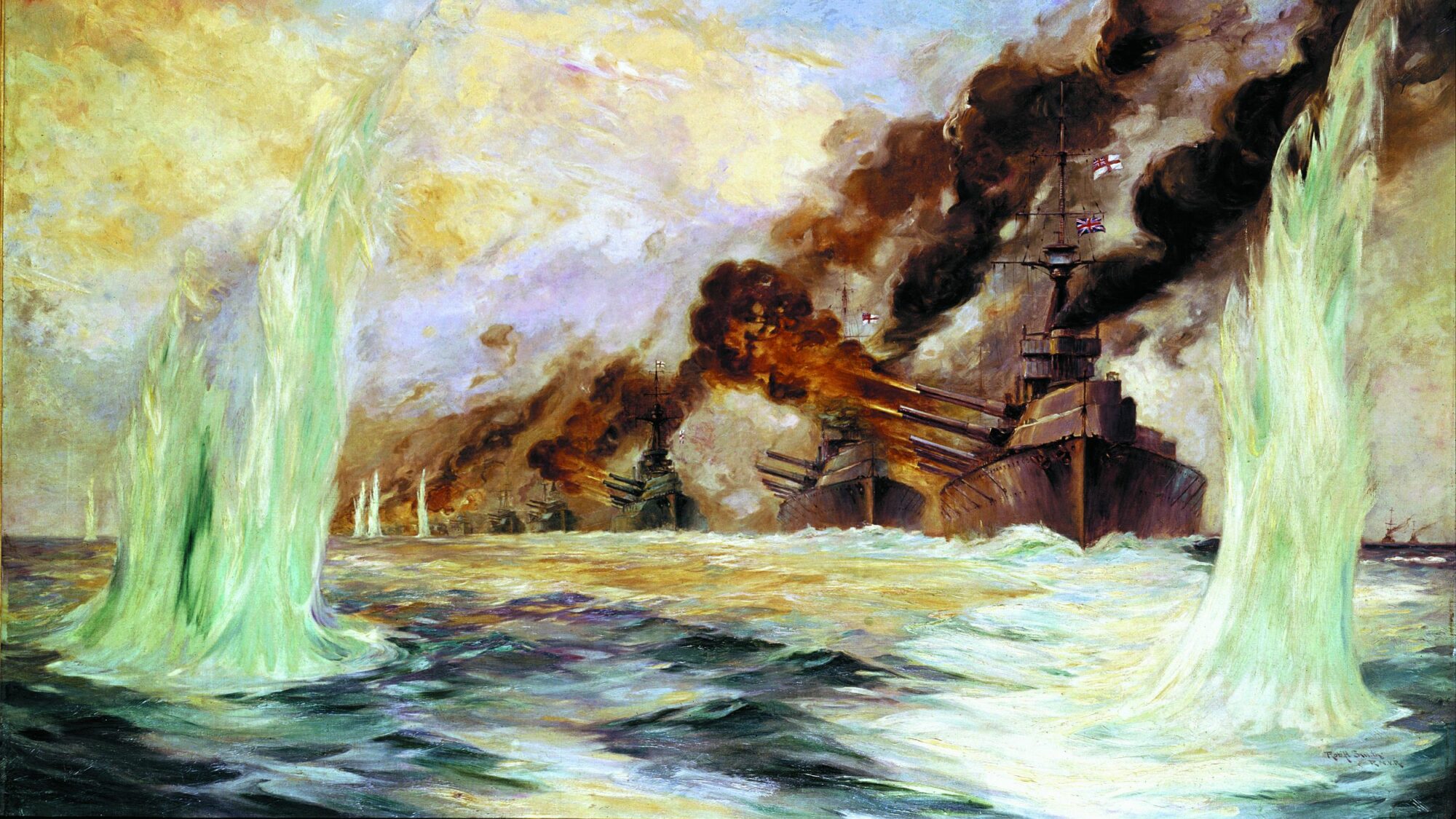

Dueling Naval Ship Doctrines

The British ships had been built for speed and power. Their guns ranged in size from 12-inches to 15-inches. The Germans, on the other hand, had smaller 11- to 12-inch guns. Only two of their ships had the larger 15-inch guns, but the Germans had thicker armor. Theoretically, all the British had to do was fire at the farthest range of their guns and keep maneuvering at higher speeds. This would keep their ships out of range of the Germans, while their own larger projectiles rained down on the enemy at will. But the German ships had a dull-gray eastern sky behind them that masked their precise position, while the British were exposed by a cloudless, sun-drenched western sky. Their vision was also obscured by smoke blowing in front of them. To make matters worse, the British rangefinders were inferior to their shooting distance, while the German scopes magnified their targets at 23 times greater than the naked eye. Unsurprisingly, they were better marksmen. The Germans were able to get the British in their sights and fired the first shots with their heavy guns. Thirty seconds later, the British line opened fire as well. The Germans had the better luck in the opening salvos. The British capital ships Lion, Princess Royal, and Tiger all took hits in the opening rounds. In return, Seydlitz was hit twice and Lutzow was struck by a salvo fired from Beatty’s flagship, Lion.

At the same time that Lion scored a hit on Lutzow, she almost went down in a white flash of cordite charges. A lucky German shot had struck Lion’s center gun turret, blowing half of the turret roof into the air. It fell on the upper deck with a resounding crash, igniting the cordite charges in the loading cages, which were about to be entered into the guns. The explosion and subsequent fire killed every man in the gun house. Only the quick thinking of the turret officer, Major F.J.W. Harvey, saved both Lion and Beatty. After the initial explosion, the mortally wounded Harvey—he had lost both legs—ordered that the magazine doors be closed and the magazine flooded. His dying order prevented the fire from reaching the rest of the stored charges. For his heroism, Harvey was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Indefatigable was not so lucky. She had been under heavy fire for about 15 minutes when there were fierce explosions in the center and rear of the ship. The 18,500-ton steel vessel disappeared from sight, the first ship sunk in the battle. The Germans were raining down hellish fire on Beatty’s five ships, but salvation came in the form of Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron, which arrived at about 1610. Although the distance was still great and the German line was shrouded in smoke, Evans-Thomas’s four ships were able to inflict enough pain on the German vessels to relieve the immediate pressure on Beatty, who smartly altered his course when he realized that Evan-Thomas had joined the battle. Hipper did the same. The fleets, which had been drifting apart and out of each other’s line of sight, came back into range and resumed firing.

Queen Mary was hit next. According to observers on board Tiger and New Zealand, three shells struck Queen Mary simultaneously. From the flying splinters and the deep-red glow of fire at the moment of impact, it seemed as though the shells had failed to pierce the armor. Two more shells struck the ship. Again, only a little black smoke, apparently coal dust, was seen to issue from the shot holes. Then a tremendous dark-red flame and large masses of black smoke belched forth amidships and the hull appeared to burst asunder. A similar explosion followed in the forward section of the ship. Queen Mary broke in two, the roofs of her turrets hurled 100 feet into the air, and in a moment she disappeared from view, with the stark exception of her stern and its still-revolving propellers. Only 20 men out of a complement of 1,286 survived the sinking.

Tiger and New Zealand, following Queen Mary in line of battle, barely avoided striking the two halves of the dying ship. When Princess Royal disappeared in a plume of water as well, Beatty said dyspeptically, “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” He sent 12 destroyers to deliver a torpedo attack on Hipper’s ships. They raced toward the German ships at 34 knots. Hipper saw them coming and sent out the light cruiser Regensburg and 15 destroyers to meet them. Both sides fired torpedoes at the capital ships. Only one out of 20 torpedoes the British fired found its mark. Seydlitz was hit hard, taking in hundreds of tons of water, but she was able to retain speed and stay in line. The British ships managed to avoid all 18 torpedoes fired at them. The destroyers battled each other in the no-man’s-land between the ships. Two destroyers were sunk on either side. During the melee, Beatty reversed course and turned north. His ships were taking the worst of it. Two of his ships had been sunk, as well as two destroyers, while the Germans had only lost two destroyers. To make matters worse, Scheer’s force was now coming into view.

Beatty Withdraws

Beatty’s light-cruiser squadron had been left behind and was just now resuming scouting positions in front of the larger ships. From this vantage point, they could see the entire German High Seas Fleet. In another 10 or 20 minutes, Beatty’s eight capital ships would have been outnumbered 21 to 8. Without the light cruisers in the British vanguard, the whole battle would have truly been a disaster for the British. Beatty’s turn left Evan-Thomas in position to inflict damage on the Germans with his huge 1,900-pound artillery shells. But Evan-Thomas, seven miles away, could not see Beatty’s message flags, nor did any of the other ships signal him by searchlight. The first he knew of Beatty’s change of course was when he passed Lion going in the opposite direction. Beatty had his signal man contact Evan-Thomas. The message flags went up at 1648 and were not hauled down until 1654, at which point Evan-Thomas made his turn. The six-minute time period brought his ships 4,000 yards closer to the Germans. Barnham was hit, Valiant was untouched, Warspite was struck three times, and Malaya avoided the concentrated fire by turning early.

The British guns scored some hits of their own on the enemy. Seydlitz, Lutzow, Derfflinger, Konig, Grosser Kurfurst, and Markgraf all suffered damage, and Von der Tann had her guns silenced and rendered useless as an offensive weapon, but gallantly stayed in the line to draw fire away from the other ships. The German guns were beginning to quiet down, and worse yet, the field of vision had changed. The Germans were now looking into a glaring sun, while the British had a clear line of sight.

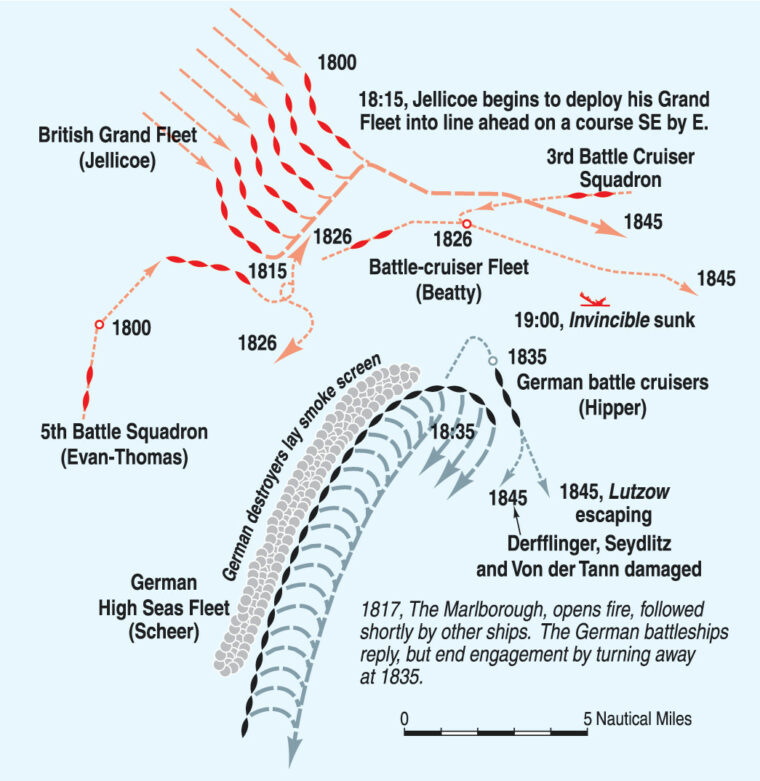

At 1720, Scheer signaled Hipper to give chase. Beatty then altered his course from north to northeast to engage Hipper’s ships again. This forced the German line to bend to the east to prevent Beatty’s ships from gaining the advantage. Smoke from the guns mixed with a heavy mist to form thick clouds that hampered Hipper’s vision. It was his job to keep the High Seas Fleet aware of changes, but because he was caught up in an intense battle with Beatty and was lost in one of the cloud banks, he did not spot the approaching British Grand Fleet. Rear Admiral Friedrich Bodicker, three miles ahead of him to the east, saw them first, reporting enemy dreadnoughts to the east. These could not be Beatty’s ships, nor could they be Evan-Thomas’s crew—someone else was entering the battle. At 1759 pm, Bodicker saw the British Grand Fleet stretched out on the horizon, 16,000 yards away.

Jellicoe Enters the Fray

When Jellicoe learned of the battle, he adjusted his course, stopped zigzagging, and picked up his speed from 15 knots to 20-—full-speed ahead. At the same time, he sent three Invincibles racing before him. They were 17,000-ton battle cruisers with eight 12-inch guns, commanded by Rear Admiral Horace Hood. These ships could steam at a full 25 knots and catch up with the running battle. The Invincibles at first had a hard time finding the battle in the open sea, appearing on the eastern side of the fight, where Hood encountered Bodicker’s 2nd Scouting Group of light cruisers. The ships were not close enough to recognize friend from foe, so they continued to close in on each other. The German ships recognized the light cruiser Chester as British and unsportingly flashed the British recognition signal, drawing Chester even closer. When the Germans opened fire at 6,000 yards, Chester was engulfed in shells and lost her rangefinder, her communications systems and three of her four 6-inch guns. Although ravaged with gunfire, Chester was not slowed down—her engines were untouched. Hood saw Chester in distress, placed his ship between the crippled vessel and the German ships, and fired his 12-inch guns. The German ships fled the scene, but not before three of the four ships were hit. Frankfurt and Pillau escaped with minimal damage, but Wiesbaden was fatally injured. A 12-inch shell put her engine out of commission, and the wounded ship stopped dead in the water and drifted.

To rescue the German light cruisers, Hipper sent Regensburg and 31 destroyers to charge the Invincibles, but before they could launch their torpedoes they were met by a countercharge from Hood’s second light cruiser, Canterbury, and four British destroyers. In a free-swinging brawl at close quarters, the Germans somehow got the impression that many more British ships were present than was the truth. As a result, the Germans only fired 12 torpedoes, after which the 31 destroyers turned back. During the brawl, the British destroyer Shark was hit and disabled. The small British losses were out of all proportion to the gain brought about by the surprise appearance of the 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron on the starboard side of the German cruisers. Had it not been for the timely intervention of Hood’s squadron, the German flotilla would have attacked Beatty’s force full-on and brought the latter’s encircling movement to a standstill.

When Jellicoe arrived near the battle scene, he desperately needed accurate and precise information, but such information was the last thing he received. One of Beatty’s most important jobs—and his greatest failure—was his failure to send messages to his commander. For over an hour and 15 minutes Beatty either ignored or forgot to inform his commander about where the enemy was, its battle strength and bearing. Jellicoe had to deploy his ships into one long line of battle in order to bring his guns to bear on the enemy. If he deployed in the wrong direction, the Germans might cross his “T,” sailing across the foremost ship in his battle line in a perpendicular fashion and inflicting heavy damage on the ships in the base of the “T.”

At 1806 pm, Beatty sighted the enemy to the south and passed the information on to Jellicoe. Still, Jellicoe did not know their speed, direction, or number. Despite this lack of information, Jellicoe had no choice but to deploy. If he turned to the starboard, he would engage the enemy quickly, being well within gunnery range. He could also come under heavy torpedo and destroyer attack from the Germans. If he turned to port, he would avoid the torpedo attacks, being 4,000 yards away from the enemy line. This move would cross the German “T” and put the British fleet against the dull-gray sky, making it hard to see, while the Germans would be highlighted by the western sky.

Scheer’s Gambit

Scheer thought he was sitting in the catbird seat before Jellicoe showed up. He had 21 dreadnoughts, with their corresponding complement of torpedo boats and destroyers, against Beatty’s eight dreadnoughts and retinue. He was about to grab his grand prize when the whole British Grand Fleet suddenly appeared. Scheer, to his credit, reacted quickly. He saw only one way out—to order a carefully rehearsed fleet maneuver designed for exactly this situation, when it was necessary to break away rapidly from a stronger fleet. At 1836 pm, Scheer signaled for each ship to make a 180-degree turn onto the opposite course.

This maneuver caught Jellicoe off guard—he was not used to being on the defensive. The Germans, on the other hand, knew that they were the weaker force and had to be ready to escape if they were confronted by an overwhelming foe. They had often practiced escaping. Had it not been for the wounded Wiesbaden and the slower ships that Scheer mistakenly allowed to accompany him, he might have escaped with minimal damage after sinking two of the Grand Fleet’s mighty dreadnoughts. But even though Scheer had made a great turning maneuver, his fleet could not outrun Jellicoe’s fleet. Scheer ordered another turn to starboard. His decision to turn back and engage the enemy again has been criticized by many. Scheer himself seemed to be hard-pressed to justify his actions after the fact. In his report to the Kaiser, he claimed, “It was as yet too early to assume night cruising order. The enemy could have compelled us to fight before dark, he could have prevented our exercising our initiative, and finally he could have cut off our return to the German Bight. There was only one way of avoiding this: to inflict a second blow on the enemy by advancing again regardless of cost, and to bring all the destroyers forcibly to attack. Such a maneuver would surprise the enemy, upset his plans for the rest of the day and, if the blow fell really heavily, make easier a night escape. It also offered the possibility of a last attempt to help the hard-pressed Wiesbaden, or at least the rescue of her crew.”

At 1855, Scheer sent the High Seas Fleet steaming straight at the full force of the British fleet. This move surprised the British, but the gamble did not pay off for the Germans. The British could see the German ships clearly, while the late-afternoon sun was blinding the German gunners, who could only make out the flashes of the British guns. Without a good target to shoot at, the Germans were sitting ducks waiting for the British hunters. Hercules fired on Seydlitz; Colossus and Revenge on Derfflinger; Neptune and St. Vincent on Derfflinger and Moltke. Marlborough, ignoring her own torpedo injury, fired 14 salvos in six minutes and saw four of them hit home. Monarch, Iron Duke, Centurion, Royal Oak, King George V, Temeraire, Superb, and Neptune all reported scoring hits. The German ships were being slaughtered and could hardly see well enough to try to hit back. During the whole time the British were ravaging the German ships, the Germans only landed two shots, both on the luckless Colossus.

A Chance at a New Trafalgar?

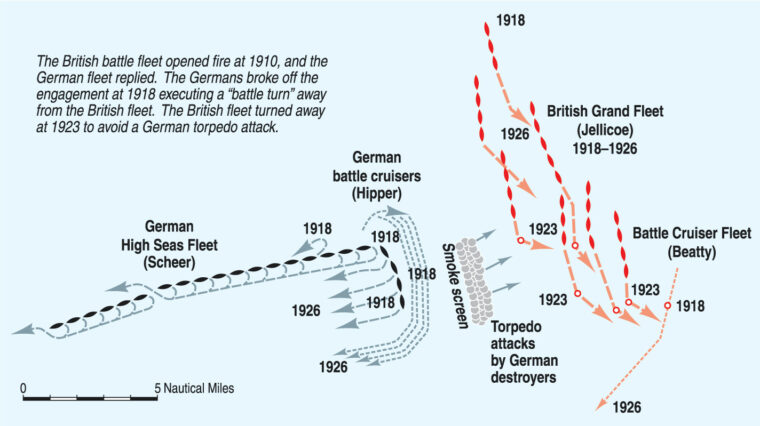

Ten minutes of withering attacks was all Scheer could stand—he would have to extricate his ships again. He sent his battle cruisers and torpedo boats to attack the enemy’s battleships and leave a smoke screen to shield their retreat. Signal flags went up commanding: “Battle cruisers at the enemy. Give it everything!” Derfflinger with eight 12-inch guns, Seydlitz with ten 11-inch guns, Moltke with its ten 11-inch guns, and Von der Tann (which could not fire its fore turret) would have to shield the German fleet from the entire British fleet, while having scores of 12-, 13- and 15-inch shells raining down upon them. The four ships were facing down the British battle line, while the German ships attempted to make another 180-degree turn. During the 10-minute-long bombardment by the British, the German battle line became bunched up, making tight maneuvering extremely dangerous. Scheer turned to port instead of starboard to make room for other ships to turn. Still, some of the ships almost collided as they attempted to turn.

The battle cruisers were followed by torpedo boats. Their job was to lay down a line of torpedoes to cover the escape of the High Seas Fleet. This they failed to do, but the secondary result of their attack nevertheless helped save the Germans. The British used a turn-away tactic that was common at this time by most navies. Upon seeing the track of an enemy torpedo, a captain would turn his ship away from it and attempt to outrace it. Some 31 torpedoes were fired at the British line, and though none of them hit their targets, by forcing the British to turn they changed the outcome of the battle. Had Jellicoe turned toward the torpedoes and pursued Scheer, instead of turning away, he might have inflicted heavy damage on the Germans and perhaps even brought about their total destruction. Instead, he sacrificed his advantages of time and range, while Scheer made good his escape. Afterward, Jellicoe was accused of forsaking the Royal Navy’s chance for a new Trafalgar. The ghost of Nelson would haunt him for the rest of his life. But to be fair to the British commander, turning away from a torpedo attack was the accepted practice of the day. Moreover, he was still between the German High Seas Fleet and their path home. The Germans would have to cross the British line to find safe harbor. As far as Jellicoe was concerned, they would do battle again at daybreak the next day.

In the Confusion of the Night

Scheer had extricated his fleet from imminent disaster for a second time, but he still had a problem. He had to take his battered ships to Horns Reef off the Denmark coast. From there the Germans had a clear lane back to the Jade River, 100 miles to the south. Jellicoe had to deliver the death blow to Scheer’s fleet before they reached Horns Reef. Scheer had one more ace left up his sleeve. The Germans were practiced at night battles, while the British were not. But daylight would come early in this northern section of the earth. Sunrise was around 0300. Scheer would have to act quickly.

At 2215, four British light cruisers met five German light cruisers. In the near-total darkness, it was hard to identify the ships. Commodore W.E. Goodenough on Southampton came in contact with some unidentified ships crossing his path and fired a shot at them. They returned fire in a barrage of shells. Although much damage was done to the British ship, she was still able to fire a torpedo, which hit and sunk the light cruiser Frauenlob. The rest of the British ships seemed reluctant to engage or even to disclose their positions at night. Because of this fear, two of Scheer’s dreadnoughts, Moltke and Seydlitz, were allowed to pass through the British lines unmolested. Both ships were heavily damaged and ripe for attack, but both were allowed to limp away.

At about midnight, the British 4th Flotilla of Destroyer Escorts, which was keeping station with the 5th Battle Squadron, converged with the van of the German High Seas Fleet. Tipperary was leading 12 destroyers when she spotted unknown ships to the starboard, about 1,000 yards away. Searchlights and a barrage of 5.9- and 3.5-inch shells turned Tipperary into a blazing hulk. Spitfire, which was behind Tipperary, had to maneuver to avoid hitting the burning ship. As she turned, she encountered the German battleship Nassau coming at her from the other direction. Nassau altered her course straight for Spitfire and the two ships collided port bow to port bow, then screeched by each other. Nassau fired her 11-inch guns at the smaller ship. Although the projectiles went over the top of the destroyer, the blast still wrecked the bridge, the foremost funnel, and the mast. Spitfire was able to limp away, but she was badly damaged and useless for the rest of the battle.

Another British captain was reluctant to fire first and paid the price. Commander Allen on the destroyer Broke signaled an unidentified ship and was met by a hailstorm of blinding lights and shells. In less than a minute, Broke was decimated and spun out of control, ramming the next ship in line, Sparrowhawk. Contest also rammed Sparrowhawk, taking off 30 feet of her stern. Broke and Contest were able to pull out of the mess, limping out of action. Sparrowhawk floated around until the next day, when she was scuttled by her crew. The German light cruiser Rostock was hit by a torpedo, taking on 930 tons of water but was able to follow the German ships slowly and from a distance.

Breaking through the British Lines

In the 4th Flotilla, command passed to Commander Hutchinson of Achates. He was followed by Ambuscade, Ardent, Fortune, Porpoise, and Garland. It was Fortune whose luck would run out. Hutchinson wanted to reconnect with the British line and steered a course merging instead with the lead of the German line. Westfalen and Rhineland opened fire. It took less than a minute to send Fortune to the bottom. Achates and Ambuscade thought they were being chased by a German cruiser. It was actually one of their own, Black Prince, an armored cruiser, which had fallen behind the British line because of damage to her engines. Soon after 0100, both Nassau and Thuringen sighted the ship, which did not reply to their signals. Thuringen open fire on Black Prince from a range of 1,000 yards. All her shots were direct hits. Nassau, Ostfriesland, and Frederick der Grosse pitched in with more fire. Black Prince blew up and sank into the North Sea, sending hundreds more British sailors to a watery grave.

Ardent was the final destroyer of the 4th Flotilla to meet the German line, be illuminated by the searchlights, and be destroyed by a hailstorm of small-caliber shells. None of the British destroyers had radioed Jellicoe about the action with the German dreadnoughts. Had they done so, they might have altered the course of the battle. The battle of destroyers versus dreadnoughts was a mismatched fight from start to finish and quickly turned into a massacre. All the while, Jellico had no idea that Scheer was successfully cutting across the rear guard of his ships and escaping. Despite other minor encounters, the German ships managed to break free. At 0415, Jellicoe learned that the High Seas Fleet had gotten away. It was only now that Beatty got around to telling Jellicoe of the loss of battle cruisers Queen Mary and Indefatigable. Jellicoe was shocked to hear the news, especially when he learned that they had been lost early in the battle and that his battleship commander had failed to keep him informed of such a catastrophe. It might have changed Jellicoe’s attitude of pursuit in order to seek revenge for the losses.

“Britain Defeated at Sea!”

As it was, the Germans claimed a great victory at Jutland. Few observers would have given the German fleet a fighting chance against the British. The naval battles of the war up to this point had gone poorly for the Germans. Great Britain reigned supreme on the oceans. But with the German fleet sinking 14 British ships and claiming a staggering 6,600 casualties, including 6,097 killed, German newspapers exulted that Trafalgar had been reversed. In a limited sense, they were correct. The German High Fleet had certainly given as good as it got. But the British still maintained a great numerical superiority in ships over the Germans, and they were building new ships faster than the Germans. Even though Queen Mary and Indefatigable had been lost, there were already ships to take their place. Nor was there a change in the relative position of the two navies. The German fleet was still stuck in its corner of the North Sea and British ships still blockaded it.

To the British public, unaware that a major sea battle had even taken place, Jutland came as a bombshell. Within an hour, London newsboys were on the streets shouting, “Great Naval Disaster! Five British Battleships Lost!” Flags were lowered to half-staff, stock exchanges closed, and theaters darkened. Overseas, on breakfast tables from New York to Chicago to San Francisco, the headlines read, “Britain Defeated at Sea!” and “British Fleet Almost Annihilated!” Soon, however, the British newspapers put things into cold perspective. “Will the shouting, flag wagging [German] people get any more of the copper, rubber, and cotton their government so sorely needs?” asked the British press. “Not a pound. Will meat and butter be cheaper in Berlin? Not by a pfennig. There is one test and only one, of victory. Who held the field of battle at the end of the fight?”

Even Scheer seemed to lose hope in the ability of the High Seas Fleet to have a definite impact on the war. In a confidential report to the Kaiser, he stated his opinion that most of the ships would be ready for action by August, but that he doubted whether even a successful attack could reduce Great Britain’s control of the North Sea. Then he added ominously, “A victorious end to the war within a reasonable time can only be achieved through defeat of the British economic life—that is, by using U-boats against British trade.” The German Navy had put up a valiant fight against the superior British Navy at Jutland, but by resuming unrestricted submarine warfare, Germany would foolishly antagonize a powerful neutral nation, the United States, and bring it into the war. By threatening America, Germany needlessly made a new enemy. When Scheer convinced the Kaiser to allow unrestricted U-boat activity to resume, Germany in effect threw away her victory at Jutland and planted the poisonous seeds that eventually would lose Germany the war.

Very good and thorough analysis of this interesting battle. I enjoyed

Excellent and pretty much explains why the German fleet was of little use for the rest of the war.

If you looking at battle casualties only to determine a victor then you will be covering only at small part. More important is how that battle fits into the overall campaign. In that case, Trafalgar and Jutland share one irrefutable fact and that is a British victory determined that the opponent would no longer be capable of invasion or even threatening British sea supremacy. Sheer spent the entire battle trying to avoid combat and to get away . If he had stood and fought his destruction was inevitable.

At the time an American journalist accurately said “The German fleet has assaulted its jailor, but it is still in jail.” The British were still on patrol.