By Patrick J. Chaisson

In the midst of the ambitious Operation Market-Garden, Brigadier General James M. Gavin, 82nd Airborne Division Commander, first heard about the crisis at Mook, along the Maas River, from his chief of staff, Lt. Col. Robert H. Wienecke.

Wienecke ran “Champion Main,” codename for the division’s command post (CP) located outside Groesbeek, the Netherlands. It was his job to keep the commanding general updated on operational matters; as such, the two men were always connected by radio. Except now the general wasn’t answering.

“Jim from Bob, Jim from Bob, come in, over,” Wienecke spoke repeatedly into a hand mike. Finally, after 30 anxious minutes, Gavin responded. His normally unflappable chief’s frantic manner came across clearly through the radio receiver.

“General,” Wienecke advised, “you’d better get back here [the CP] or you won’t have any division left.”

It was 1330 hours on Wednesday, September 20, 1944. As his jeep sped off to Champion Main, Gavin fretted over this ominous warning. What could possibly be so serious as to require his immediate attention?

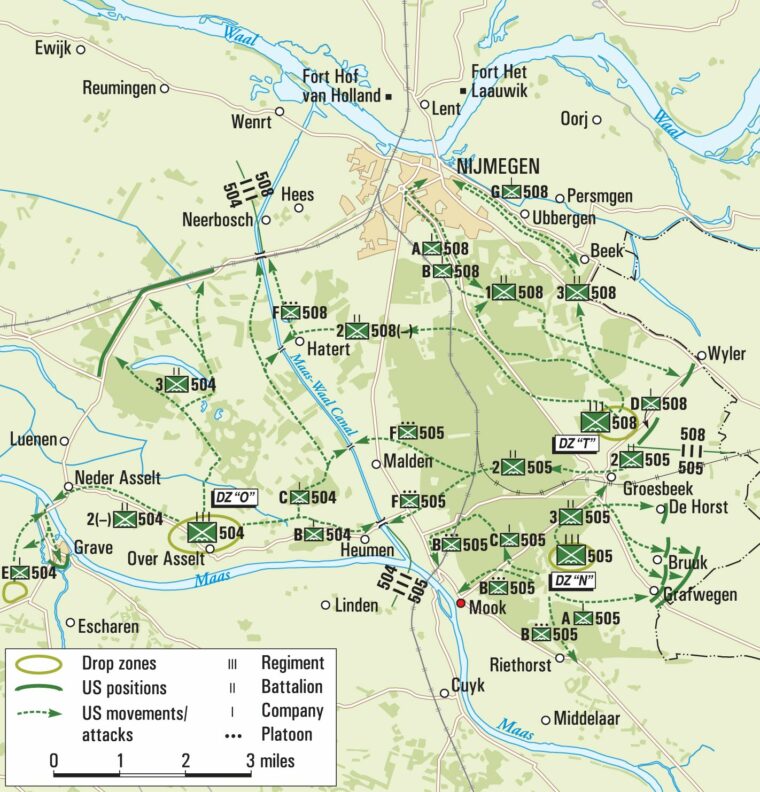

Three days earlier, 7,250 men of the 82nd “All-American” Division parachuted or rode by glider into Holland alongside their comrades in the U.S. 101st “Screaming Eagles” and British 1st “Red Devils” Airborne Divisions. Their task was to open and hold 64 miles of roads and bridges leading to the Rhine River bridge at Arnhem, over which XXX Corps—vanguard of the British Second Army—would advance and open an invasion route into northern Germany.

Market-Garden’s mission order demanded speed, surprise, and a healthy dose of optimism regarding the enemy situation. Allied commanders recognized that many things had to go right for the scheme to succeed. Above all, their lightly equipped airborne soldiers needed to take and hold several key bridges over five major waterways. Any delay caused by weather, traffic congestion, or German counter attacks could prove disastrous—especially for the Red Devils fighting around Arnhem.

The 82nd Airborne’s paratroopers and glidermen bore responsibility for nine bridges in their area of operations. Of special concern were the one railroad and two highway spans that traversed the wide Waal and Maas Rivers. These massive structures had to be seized intact, as did at least one of four crossings over the smaller Maas-Waal Canal.

The city of Nijmegen, on the Waal’s south shore, could pose additional problems for Gavin’s division if resolute defenders were encountered there. Two crucial bridges, one built for rail and the other for road traffic, ended inside the city center. Should German forces manage to block the way, it would require a costly and time-consuming urban assault to defeat them.

The All-Americans also had to seize a long, wooded ridgeline about six miles southeast of Nijmegen called Groesbeek Heights. A triangle-shaped plateau reaching some 300 feet above the surrounding area, this high ground dominated all friendly approaches to Nijmegen. It also covered several counterattack routes leading from the heavily forested Reichswald region of Germany only three miles to the east.

Whoever held Groesbeek Heights also controlled a large open area labeled Drop Zone (Landing Zone) “N.” This was the 82nd Airborne’s main logistics hub, onto which Allied transport aircraft would deliver glider-borne reinforcements as well as rations, medicine, and munitions. Until XXX Corps punched through to Nijmegen, aerial resupply was the only way Gavin’s unit could keep fighting.

To accomplish its assigned missions, the All-American Division had available a mere 7,250 troopers on the first day of Market-Garden. In no way could this number of men be considered adequate. Jim Gavin remarked that he really needed two divisions at Nijmegen, but a shortage of troop carrier aircraft dictated the 82nd Airborne enter battle on September 17 with only three of its four infantry regiments.

The 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), back with the division after detached service in Italy, was directed to grab the 1,200-foot-long Maas River bridge at Grave along with several smaller spans over the Maas-Waal Canal. The combat tested 508th PIR had the task of securing Groesbeek Heights’ northern half, including the villages of Beek and Berg en Dal. The 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (PFAB) and its dozen 75mm pack howitzers would also jump in to provide immediate fire support, while eight 57mm anti-tank (AT) guns from Battery A, 80th Anti-Aircraft Battalion, were set to arrive by CG-4A “Waco” glider later that afternoon.

Making its fourth combat drop of the war, Colonel William E. Ekman’s 505th PIR was responsible for the 82nd’s right flank along Groesbeek Heights. Ekman needed to cover this six-mile line with only two battalions, as his 2nd Battalion had been taken away to act as division reserve. In the north, 3rd Battalion (Major James L. Kaiser commanding) would occupy Groesbeek while maintaining contact with the 508th. On the right, Major Talton W. Long’s 1st Battalion was to seize key terrain along the regiment’s southern flank.

Major Long’s command consisted of three rifle companies (A, B, and C), plus a heavy weapons platoon. Holding Company A in reserve, Long ordered Company C to establish a line of blocking positions facing east. Company B had to take two villages named Mook and Riethorst, plus the Maas River railroad bridge. This outfit also needed to control a vital roadway leading in from the enemy stronghold of Gennep.

It was a difficult assignment, but Company B proved equal to the task. Brought back up to strength after heavy fighting in France, the unit possessed a healthy mix of combat veterans and fresh replacement troopers. Some old timers, like Sergeant Harvill W. Lazenby, had already parachuted into Sicily, Salerno, and Normandy. First Lieutenant Stanley Weinberg ably led 2nd Platoon into battle on D-Day, while 20-year-old bazookaman Private Northam H. Stolp would experience his first combat in Holland.

Commanding the approximately 145 paratroopers assigned to Company B was 1st Lt. James M. Irvin, a long-serving officer whose escapades in France became the stuff of legend. Jumping out into the darkness on June 6, 1944, he accidentally landed inside a German artillery emplacement and was instantly captured. While en route to a POW camp, he made his escape to find shelter with the Resistance. In August, Irvin successfully made his way back to England where he resumed command of Company B in time for the Market-Garden operation.

When told they would likely be facing “old men and children,” Irvin’s veterans scoffed. Most of them had already learned the hard way never to underestimate their foe’s skill and tenacity in battle. And while the 82nd’s main opposition on September 17 consisted of easily stampeded Luftwaffe antiaircraft gunners and rear echelon personnel, a more robust German response was not long in coming.

Field Marshal Walter Model, commanding Army Group B from his headquarters just 18 miles from the Groesbeek drop zones, wasted no time in organizing a counterattack. Quickly mobilizing German Army, Luftwaffe, and SS forces scattered across the Netherlands and western Germany, Model directed his local commanders to form ad hoc “kampfgruppen” (combat teams) with whatever troops and equipment they could scrape together.

One such organization was Corps Feldt, named for its commanding officer General Kurt Feldt. Stationed on the Lower Rhine, Corps Feldt’s primary mission involved constructing fortifications along a segment of the Westwall, or Siegfried Line. It controlled just one subordinate command: Lt. Gen. Gerd Scherbening’s 406th Infantry Division. Initially, this outfit contained a headquarters staff and some reserve units made up of convalescents (so-called “stomach and ear” men), unassigned replacements, and searchlight crews.

Scherbening faced enormous problems on September 17. None of his riflemen possessed any infantry training, nor did the Germans have adequate communications, artillery, or logistical support. By requisitioning every serviceable motor vehicle in its sector, however, the 406th Infantry Division managed to push forward a growing number of reinforcements to establish attack positions inside the Reichswald.

Model did not expect Corps Feldt to defeat the American invaders; rather, he needed it to buy time so his staff could organize and send forward a more formidable counterattack force. This formation, the II Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Corps, had for the past few months been rebuilding its ranks from what remained of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Divisions. Although no longer capable of conducting airborne operations, these well-armed and battle-wise troops represented an extraordinarily deadly threat to the overextended 82nd Airborne Division.

Yet it would take time to move the men of II Parachute Corps up from their encampments near Cologne via the Third Reich’s war worn rail network. In a cable to Model, corps commander Lt. Gen. Eugen Meindl estimated his Fallschirmjäger should be in position by daybreak on Wednesday, September 20. Until then, the flak gunners, supply troops, and trainees already in place around Nijmegen needed to hold on.

Those Germans were still full of fight, though, as Company B’s Lieutenant Stanley Weinberg discovered on the afternoon of September 17. Preparing to jump from his C-47 transport aircraft, Weinberg experienced a close call with some enemy antiaircraft crews. “Just before I got up to stand in the door to look for familiar landmarks,” he wrote, “a bullet came through the floor in the doorway.” Luckily, no one in his plane was hit by that burst of flak.

Moments later, at 1310 hours, the green “go” light came on inside Weinberg’s C-47. Within a few minutes, every member of Company B jumped onto DZ “N” in the first Allied daylight parachute assault of World War II. The 505th PIR’s historian enthusiastically called it “a perfect drop.”

Sergeant Harvill Lazenby, who survived the chaotic nighttime jump into Normandy, marveled at the improved discipline shown by U.S. Army Air Forces transport pilots over Holland. “The most impressive thing I recall was the troop carrier group that brought us in. They made a 180-degree turn after the drop—the flak guns were really hitting them. They held their formation while burning and never broke formation until they fell.”

Once assembled on the drop zone, most of Lieutenant Irvin’s men moved out toward their initial objective—high ground east of Bisselt—while other troopers collected equipment bundles containing the company’s radios, light machine guns, and extra ammunition. Also stowed inside those canisters were Browning Automatic Rifles, newly authorized to increase each infantry squad’s firepower. Known as BARs, these weapons would soon make their presence known all along the Groesbeek Heights.

The soldiers of 1st Platoon, led by 1st Lt. William J. “Buck” Reardon, stepped off at 1730 hours toward the railroad span north of Mook. A line of dug-in Germans momentarily blocked their way; those troops surrendered after a brief scuffle. This action, however, consumed precious minutes and alerted all within earshot to the Americans’ presence. Continuing on, Reardon’s men ran into machine-gun fire from a second, more determined group of defenders about 400 yards from their destination.

Taking cover in a ditch, Harvill Lazenby “got a small-arms bullet in my ankle [that] almost took my foot off.” As his fellow paratroopers deployed for a hasty attack, the sergeant noticed German engineers setting explosives on the bridge that 1st Platoon was attempting to capture.

“One squad flanked to the right,” an observer stated, while “the remainder of the platoon got to the bridge, which was blown up just as they reached the railroad tracks.” Two G.I.s were killed and three wounded in the blast.

Although Reardon’s outfit did not accomplish its primary mission of grabbing intact the Maas River bridge, much work remained to be done. Running underneath the railroad overpass was a highway leading straight toward enemy-held territory. First Platoon’s riflemen spent most of the night establishing roadblocks all around this chokepoint.

Meanwhile, 1st Lt. Stanley Weinberg’s 2nd Platoon—reinforced by a 14-man machine gun section from Headquarters Company—began moving toward the hamlet of Riethorst. Emerging from a woodlot north of Plasmolen, Weinberg’s men saw several Germans wiring a nearby ammunition dump for demolition. Before his paratroopers could react, however, an enormous explosion went off.

Assaulting through the debris, Weinberg’s men rapidly cleared Plasmolen. Leaving behind some machine gunners for local security, the rest of 2nd Platoon continued on toward Riethorst. Along the way they ambushed a German staff car, killing Lt. Col. Siegfried Harnisch while capturing his driver and another Wehrmacht officer.

Second Platoon secured Riethorst—a small settlement of perhaps 30 residents—by 1530 hours. Weinberg established his platoon CP on high ground that covered both the village and a main roadway. Other troopers, armed with light machine guns, BARs, and bazookas, set up outposts meant to provide early warning of enemy patrol activity.

They did not have long to wait. At 1630 hours, soldiers manning the strongpoint under Sergeant Frederick W. Gougler killed a bicycle-mounted scout seen moving west along the Nijmegen-Gennep road. A platoon of Germans then rose up and stormed the Americans’ positions. The fighting grew so intense that one of Gougler’s machine guns overheated, forcing his gunners to draw their .45 caliber pistols in self-defense.

Weinberg sent forward reinforcements and called in artillery fire, which forced the foe to retreat. Yet 2nd Platoon would need help to hold Riethorst, a realization acknowledged by 1st Battalion’s commander Major Long. Shortly after sunset, Long dispatched Lieutenant Harold L. Gensemer’s 1st Platoon, Company C, to support Weinberg. The two lieutenants divided responsibility for their hilltop bastion, with Weinberg’s platoon to the south and Gensemer’s soldiers occupying the northern side.

Few men got any sleep that night. Sometime after 0100 hours on September 18, a large group of Germans attempted to infiltrate the paratroopers’ outposts. These soldiers represented the lead element of an escalating response to the Market-Garden landings.

Once he learned that Allied forces were dropping on Nijmegen, the 406th Division’s General Scherbening started deploying several hastily assembled combat teams to develop the situation. One of these organizations, Kampfgruppe (KG) Goebel (named for the officer commanding it), was directed to penetrate the enemy’s southern flank at Mook and continue its attack another mile or so downriver to seize the Maas-Waal Canal’s lock bridge at Heumen.

This was a tall order for the approximately 350 soldiers under Goebel’s command. Many of them came straight from a combat engineer training school and lacked heavy weapons such as mortars and machine guns. Yet, somehow Goebel managed to acquire three self-propelled “Wirbelwind” (Whirlwind) antiaircraft gun platforms. The 20mm automatic cannons mounted on these tank-like vehicles could shred unprotected infantry with ease.

U.S. intelligence officers recorded the presence of three PzKpfw. V “Panther” tanks in Company B’s sector, a claim unsubstantiated by German sources. American paratroopers frequently misidentified enemy armor throughout the war; their Panther sightings on September 18 were likely Goebel’s Wirbelwinds.

Around 0700 hours, Lieutenant Richard H. Brownlee from Company C had just positioned an automatic rifle team near Riethorst when one of the Wirbelwinds came into view. “Our two BAR men engaged the tank and received for their efforts a direct hit from the tank, killing both men,” he reported.

The German gunners next targeted their opponents’ hilltop redoubt. “We started to receive very heavy fire from the tank with twin guns mounted,” Brownlee remembered. “He was really stripping trees—and men.” Gensemer and Weinberg tried bringing artillery down on the Wirbelwind, but were frustrated to learn the 376th PFAB was rationed to five rounds per fire mission due to ammunition shortages.

Individual paratroopers then began moving forward to defeat this fearsome machine. “Corporal Allison took a bazooka to the forward south edge of the hill on a level with the tank to try to get at it,” Brownlee’s account continued. “But because it had sheets of steel [mounted on the sides] around its treads he couldn’t damage it.”

Other G.I.s attacked the Wirbelwind with a British-designed anti-tank weapon, the sack-like Mk 82 Gammon bomb. Brownlee recalled how “several of the men…tried to throw Gammon grenades down into it without success.”

Pinned down on the summit, American soldiers could only watch helplessly as KG Goebel’s troops pushed on toward Mook. Weinberg warned his company commander of the approaching threat, but with just two understrength platoons (Buck Reardon’s 1st and 2nd Lt. Emil H. Schimpf’s 3rd) available, there was little Jim Irvin could do about it except tell his men to dig in deeper and get ready.

That morning, a crisis to the north prevented 1st Battalion from assisting the beleaguered defenders of Mook and Riethorst. Occurring simultaneously with KG Goebel’s attack, some 2,300 soldiers organized into three battle groups came boiling out of the Reichswald intent on capturing the vast drop zone (DZ “N”) now renamed and marked as landing zone “N” (LZ “N”) for glider landings.

Over 450 CG-4A cargo gliders were due to arrive at 1430 hours, which meant LZ “N” had to be cleared immediately. Starting around 1240 hours, the troopers of two rifle companies—one from 1st Battalion and another with 3rd Battalion—dashed forward while firing from the hip and yelling like demons. They were soon joined by a pair of combat engineer companies fighting as infantry. This bold counterthrust caused panic among the Germans’ poorly trained conscripts and pushed them back to their start points inside the Reichswald. After clashing briefly with Company B outside Mook, Goebel’s troops also retreated.

In the glider assault that followed, Gavin’s division received nearly three full battalions of airborne field artillery along with another battery of 57mm anti-tank guns. Later, a resupply mission flown by 131 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force parachuted in 258 tons of supplies. Included in this drop was a large quantity of sorely needed artillery projectiles, mortar rounds, and small arms ammunition.

What Gavin needed most, though, was infantry. His own 325th Glider Infantry Regiment was not due to arrive for another day weather permitting, while at last report Second Army’s spearhead had not progressed much past Eindhoven—40 miles to his south. The unexpected attack on LZ “N,” plus a nagging realization that his paratroopers had yet to capture those critical bridges inside Nijmegen, greatly troubled the young general at day’s end.

Yet as the sun rose on Tuesday, September 19, so did Jim Gavin’s spirits. At 0830 hours he looked on while a column of British tanks rolled north over the bridge at Grave and into the 82nd Airborne’s perimeter. “It is difficult to describe my feeling of elation at that moment,” he wrote of the Guards Armoured Division’s arrival. With XXX Corps now bolstering his defenses, Gavin could finally focus on seizing the Nijmegen bridges. The Red Devils, fighting unsupported at Arnhem for nearly three days, urgently needed those structures in Allied hands.

For Lieutenant Irvin’s troopers situated at Mook and Riethorst, September 19 was spent improving their fighting positions, replenishing ammunition supplies, and welcoming two 57mm gun crews that came forward to help deal with enemy armor. Combat patrols also went out regularly, netting dozens of stragglers left behind in the previous day’s attack.

As the day wore on, however, there appeared several signs of a new and dangerous adversary nearing the battlefield. The 505th PIR’s commander, Colonel Ekman, was making his rounds along the perimeter when Dutch civilians told him they saw 500 Germans moving north toward Riethorst. At sunset, paratroopers all along the 505th’s line reported receiving one or two rounds of large-caliber artillery. The foe seemed to be “registering” his big guns—sighting them in—for future fire missions.

Concealed by the impenetrable Reichswald Forest, thousands of battle-hardened German combat troops began making final preparations for a dawn attack on the 82nd Airborne Division’s eastern flank. Their commander, Lt. Gen. Meindl, had learned much about his adversary’s dispositions from Corps Feldt’s nearly successful foray the day before. Meindl believed the men of II Fallschirmjäger Corps, who were much better armed, trained, and supported than Feldt’s scratch force, could easily puncture the Americans’ fragile defensive lines.

Adopting Feldt’s scheme of maneuver—a four-pronged assault designed to drive the Allies off Groesbeek Heights—Meindl added to it several elements of combat power such as additional field artillery, “Nebelwerfer” rocket launchers, and mobile flak guns firing in the infantry support role. Three Kampfgruppen, Becker, Furstenberg, and Greschick, were to recapture the villages of Wyler, Beek, and Groesbeek. Meindl’s fourth battle group, named after its commander Lt. Col. Harry Hermann, would seize Riethorst, Mook, and the Maas-Waal Canal bridge at Heumen.

Hermann’s outfit included two understrength battalions from the 5th Fallschirmjäger Division (gutted in Normandy that summer), as well as those survivors of KG Goebel still willing to fight after their failed attack on Monday. Goebel’s Wirbelwinds were on hand along with a battery of airborne field guns. Altogether, this combat team numbered 650-700 fighting men as it prepared for action during the early hours of Wednesday, September 20, 1944.

Opposing KG Hermann were four understrength platoons of U.S. paratroopers. Weinberg and Gensemer still occupied that strategic height of land near Riethorst, while Reardon and Schimpf shared responsibility for Mook. Two 57mm guns provided anti-armor defense, and forward observers from the recently arrived 476th PFAB kept watch from their perch in a church steeple. Yet company commander Lieutenant Jim Irvin could not stop worrying about his unit’s ability to contain another large-scale attack.

Located along the Maas River’s east bank, Mook boasted a wartime population of 2,100 inhabitants. Sadly, many residents chose to ignore Irvin’s strongly worded advice that they evacuate. A baker named Dinnissen, for instance, kept busy turning bread even as Nebelwerfer rockets exploded outside his front door.

At Riethorst, Lieutenant Weinberg noted this barrage started at 1100 hours and continued for three full hours. One of Weinberg’s troopers, Pfc. Robert Yeiter, endured the shelling from a nearby outpost until he spied some Fallschirmjäger closing in. Yeiter and a buddy decided to retreat up the hill.

“I remember diving over a chicken wire fence,” he said later, swearing the obstacle measured seven feet tall. Yeiter and his companion both “hit the top [of the fence] with our bellies, and flipped over on our feet on a dead run for 50 yards to a stone wall, with bullets skipping all around us.”

While most of KG Hermann’s infantry swept on toward Mook, a large detachment moved up against Weinberg’s stronghold. American riflemen, machine gunners, and BAR teams caused many casualties, but the enemy possessed superior numbers. Charging through a rain of mortar fire, exultant Fallschirmjäger reached the hilltop and began rooting stubborn G.I.s out of their holes.

Shouting out orders to take cover, Weinberg called an artillery strike down directly on his own position. The fast-shooting 476th PFAB responded with a full battalion’s worth of high explosive fury. It worked; those Fallschirmjäger unhurt by flying fragments stumbled back down to safety. The fighting at Riethorst devolved into a stalemate, with Hermann’s men dug in along the base of the hill and Weinberg and Gensemer’s platoons occupying its summit.

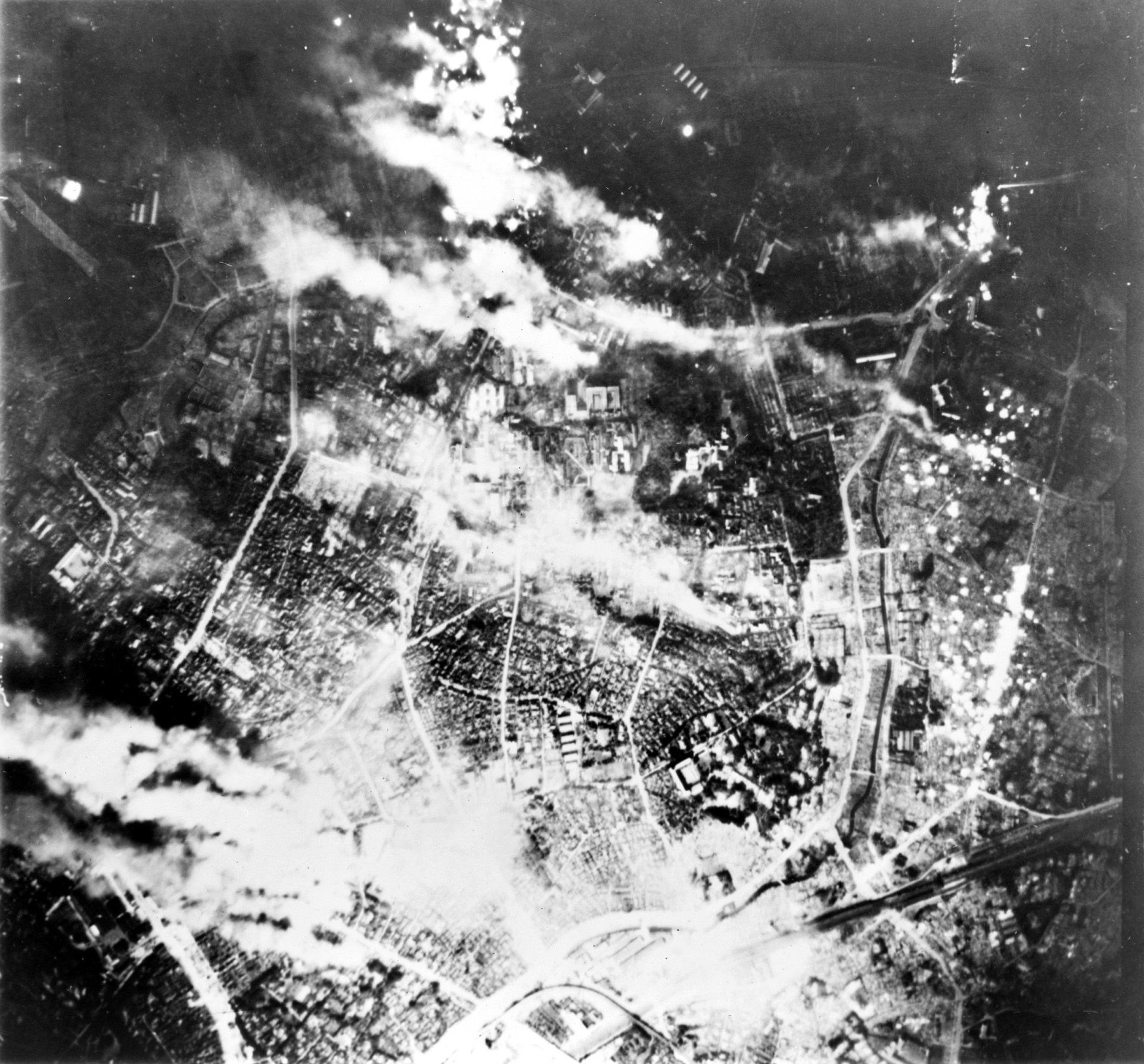

Meanwhile, in Mook heavy shelling caused residents and paratroopers alike to seek shelter. Buildings caught fire and collapsed; the 476th’s artillery spotters were blasted out of their steeple-top observation post by an unseen high-caliber weapon. At 1400 hours, German infantry charged into town.

Buck Reardon’s 1st Platoon caught the brunt of this attack. Although his men fought courageously, Reardon knew he could no longer hold and ordered a withdrawal. Half the platoon made it back inside the town, but at least a dozen troopers were either killed, wounded, or captured. Both 57mm anti-tank guns also had to be abandoned.

Just outside the village, 3rd Platoon prepared to make a final stand against KG Hermann’s rampaging Fallschirmjäger while Lieutenant Irvin radioed for reinforcements. Located just 1,200 yards behind them was the Maas-Waal Canal bridge at Heumen—the sole crossing point over this waterway sturdy enough to support British armor. It could not fall to the foe.

Irvin’s message reached the 505th PIR’s command post, where a radioman scribbled “Plenty Trouble Mook” into his operations journal before advising Colonel Ekman of this new threat to the regiment’s flank. Ekman forwarded the report to Lt. Col. Wienecke at Champion Main, then took off by jeep to see what was going on.

Arriving at Irvin’s CP at 1500 hours, Ekman observed a large number of Germans organizing for an assault on the Heumen bridge. Knowing that Company B could not stop them unsupported, he directed two reserve platoons from Company A to move forward on the double. Ekman also called up six British-crewed Sherman tanks from the Coldstream Guards’ 1st Battalion.

Inside Mook, Reardon and his paratroopers sniped away at unwary adversaries from their hideouts in residents’ basements. In an attempt to silence them, Fallschirmjäger began tossing explosives down cellar stairways. Tragically, several civilians perished this way—the Thoonen family lost six people to German grenades, including 15-month-old toddler Maria Wilhelmina.

The 82nd Airborne’s entire eastern flank staggered under II Fallschirmjäger Corps’ violent attacks. The crisis required Brig. Gen. Gavin’s personal leadership, but he was miles away supervising a daring river crossing operation at Nijmegen. Bob Wienecke, whose CP stood right in the foe’s line of march, needed his commanding general present to make plans and issue orders.

Once Gavin realized what was going on in Mook, however, he promptly set out to take charge of the situation. In the meantime, Lieutenant Emil Schimpf’s 3rd Platoon—perhaps 20 men strong—conducted a spoiling attack straight through the village. One of these paratroopers was a recent replacement named Private Northam Stolp.

“We were spread out on a generally east-west line,” Stolp wrote of the fighting that afternoon. “The town was probably two or three blocks wide.” He described how his fellow G.I.s advanced “one building at a time…shooting their way in and through them.”

Later, a machine gun pinned Stolp’s bazooka team down behind a large elm tree. “It [the enemy fire] was almost at ground level, affording us only about 18 inches of safe space over our prostrate bodies. The bits of tree were getting in our eyes…. It was like being under a buzz saw in a sawmill!”

By 1700 hours, however, Company A’s riflemen and Shermans from 1st Battalion entered the fight. Stolp described how “a British tank came up on our side of the street. It was blasting away with its .50-caliber and its cannon.” He and his comrades “were damned glad to hear and see it coming.”

Then a Panzerfaust rocket, likely launched from inside Dinnissen’s bakery, struck the Sherman. “It blew up the tank, and everything went with it,” Stolp recorded. Another M4, commanded by a Guardsman named Sergeant Capp, lost one of its tracks to a Panzerfaust but kept firing until all ammunition on board was expended.

At about this time, General Gavin’s jeep reached the railway overpass north of town. “A tremendous amount of small-arms fire passed overhead,” he recalled of that moment. In response, Gavin told his aide, 1st Lt. Hugo V. Olsen, and an NCO named Sergeant Walker E. Wood to climb up on the railroad bank and fire back at any targets they could see.

The only friendly forces present were one visibly shaking bazookaman and a British Sherman. Unfortunately, that vehicle ran over an American land mine while attempting to withdraw; its crew then “jumped out and took off” for the rear. Yet the sight of their division commander sharing the hazards of frontline combat with them inspired many paratroopers; slowly, the initiative shifted in their favor.

Stunned by the Allies’ ferocious counterattack, more and more Germans began to surrender or retreat. Towards dusk, Colonel Ekman reported that the situation in Mook now appeared under control. Reassured by this news, General Gavin turned his attention to another tactical emergency occurring farther north along the division’s perimeter. First, though, he met briefly with Lieutenant Irvin.

“Tough fight, Jim?” he asked the lieutenant, whom Gavin had known since North Africa.

Irvin replied with the easy familiarity of a fellow combat veteran. “Tough fight, Jim,” he agreed.

Mook had been recaptured, yet Irvin’s G.I.s could not continue pursuing the foe out of town until they received more ammunition. Company B did not reach the isolated strongpoint at Riethorst until after daybreak on Thursday.

The savagery of this battle was borne out by its long casualty list. A total of 20 U.S. paratroopers were killed at Mook, with an additional 54 men listed as wounded in action and seven missing. The fighting at Riethorst took 13 American lives, as well as 22 wounded. German casualties are unknown.

The inhabitants of Mook also suffered heavily, as Private Stolp attested. While sitting in a small orchard at sunset, he witnessed “a formless mass” of civilians rush out of the burning village. “People were staggering, falling, trying to run,” he wrote. “All were screaming and hollering at the top of their lungs.” The memory of that horrible night would haunt Northam Stolp for years.

After the war, James Gavin characterized September 20, 1944 as “a day unprecedented in the 82nd Airborne Division’s combat history.” His men, with significant assistance from the Guards Armoured Division, not only seized the Nijmegen bridges but also blunted a major counterattack along Groesbeek Heights. Pitted against regimental-sized formations of elite Fallschirmjäger, Gavin’s “little groups of paratroopers”—never exceeding two platoons in strength anywhere on the battlefield—somehow held onto every objective they were ordered to defend.

Gavin also claimed that Market-Garden was the most difficult campaign in which his division ever participated. Those troopers who fought alongside him at Mook and Riethorst surely agreed with this assessment.

Patrick J. Chaisson writes from his home in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Mr. Frits Janssen of the Remember September 1944 Museum in Mook, the Netherlands, for his assistance with this article.

Very nice article, thank you both Patrick J. Chaisson and Mr. Frits Janssen