By David H. Lippman

An American advertising poster for one of their bombers showed a cartoon of a smiling pilot over the captioned question, “Who’s afraid of the big Focke-Wulf?”

Bombardier Charles Hudson saw that poster placed in his crew room. Minutes later, a piece of paper was pinned to it with a note saying, “Sign here.” Every flier in the group — including the group commander — signed the paper.

They had good reason to fear the new Focke-Wulf 190. It was Germany’s last piston-driven fighter of World War II, a powerful machine that gave immense grief to American bombers over the skies of the Reich, as one of the Luftwaffe’s most dependable aircraft.

The Fw-190 owed its origins to a pre-war competition run by the German Air Ministry for new fighters to equip the equally new Luftwaffe in 1934. Professor Kurt Tank created the parasol-winged Fw-159. It was inferior to the Arado 89, He-112, and the Me-109. The latter two were slightly similar, but Willy Messerschmitt’s plane won because of its lightweight performance.

Focke-Wulf and Tank tried again in 1938 with a radial-engined fighter, equipped with a powerful BMW 801 engine. It flew for the first time in July 1939.

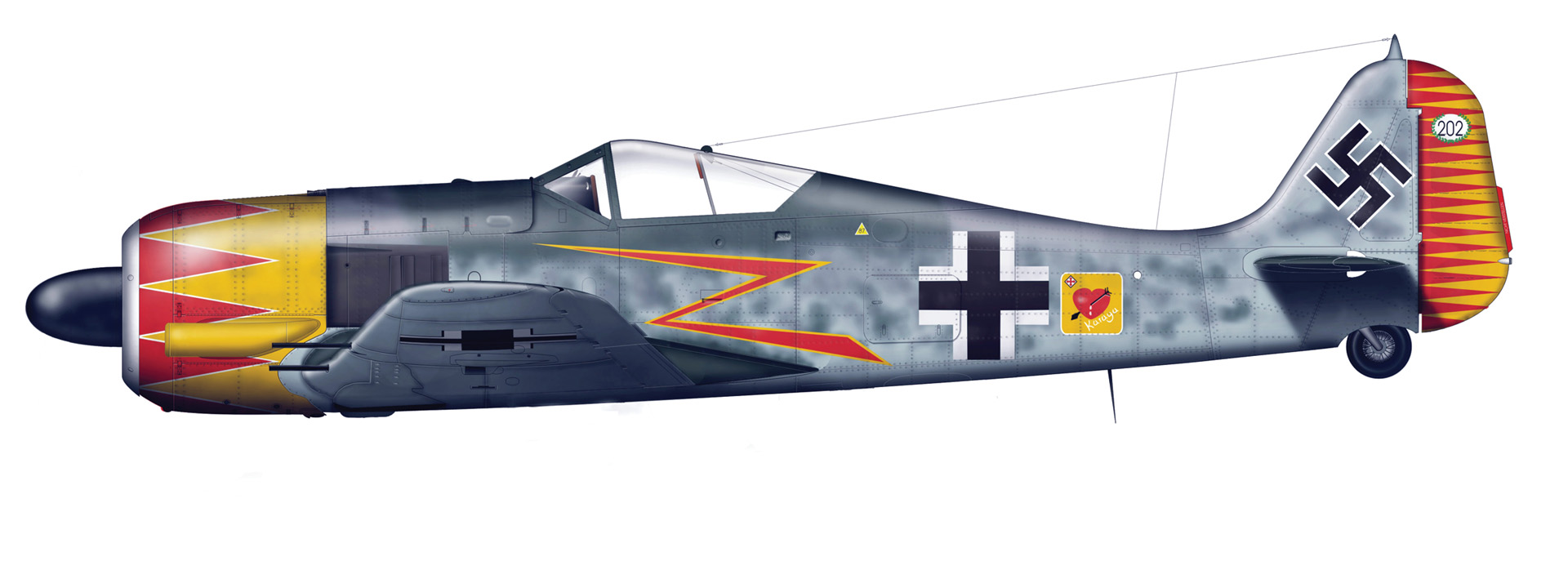

Called the “Sturmvogel” (Storm Bird) or “Würger” (Shrike) by its pilots, the Fw-190 was built unlike other fighters: a large engine on the small airframe. Tank saw the Me-109 and RAF Supermarine Spitfire fighters as racehorses in the air. He wanted a breed of fighter that could operate in harsh conditions and badly prepared frontline airfields, maintained by ground crew with short training. Therefore, the Fw-190 had to absorb battle damage and still return to the fray. It would not be a racehorse, but a “cavalry horse.”

Other advantages the design team came up with included measures that reduced the aileron and rudder trim burden on the pilot. Its electrically powered undercarriage was more reliable and rugged than hydraulic systems.

The Fw-190 was soundly constructed and flew well, yet it did not impress at first. The engine suffered repeated overheating problems, and these remained unsolved by 1941, when the first planes were delivered to their major user, Jagdgeschwader (JG) 26, an elite fighter wing defending the English Channel coast.

Called the “Abbeville Boys” by the British for the French town near their base, Lt. Col. Adolf Galland, one of Germany’s most capable and colorful fighter aces, commanded the JG 26. The wing was a squadron of aces who built up their bag in daylight battles against British daylight “Rhubarb” offensive fighter sweeps over France and “Circus” bomber strikes.

The Fw-190 A-1, the initial version, had a speed of 404 mph at 20,500 feet, an operational range of 592 miles, and packed two 7.92mm machine guns and four 20mm cannon. The Fw-190 flew at 391 mph (629 kph), weighed 8,700 pounds (3,945 kg) and had a maximum altitude of 34,775 feet (10,800 meters).

The Fw-190 A-1, the initial version, had a speed of 404 mph at 20,500 feet, an operational range of 592 miles, and packed two 7.92mm machine guns and four 20mm cannon. The Fw-190 flew at 391 mph (629 kph), weighed 8,700 pounds (3,945 kg) and had a maximum altitude of 34,775 feet (10,800 meters).

JG 26 was assigned the Fw-190 to replace its Me-109Fs, which were under gunned and worn out from heavy use. However, initially, the Fw-190 seemed no improvement because of its breakdowns and lingering mechanical issues.

The Luftwaffe had to move a detachment of their operational test squadron from Berlin to Paris to solve the engine problems. Ground crews—known as “black men” in the Luftwaffe for their uniforms—tore apart engines and found inadequate cooling, ruptured oil and fuel lines, and runaway propellers, which they struggled to address. Leaking fuel lines left pilots dazed from the fumes, unable to emerge from their planes unaided. Test planes flew over Le Bourget in Paris, smoking and stinking.

Other issues, like failing connecting rods, were more fundamental and were the results of Germany’s shortages of metals necessary to create true high-strength, high-temperature alloys. Because of this, the BMW 801 engine would be a major nuisance for the Fw-190 as long as it was in service. Even so, making the Fw-190 ready for service required 50 modifications, whose approval had to go through the intricate German bureaucracy. The Luftwaffe wanted to scrap the plane, until their top brass saw its success where it counted—in battle.

The Fw-190 fighter made its combat debut on August 16, 1941, with indifferent results. JG 26 trained on both flight and maintenance of the temperamental plane with no crashes—though German flak downed one. The pilots gained confidence and on September 18 shot down four Spitfires without a loss.

Successes like these impressed the Luftwaffe high command, which ordered the Fw-190 A2, with an improved engine and 20mm wing-root guns timed to new interrupter gear. Most importantly, engineers rerouted the exhaust to deal with the engine overheating.

Back at the Western Front, Fw-190s struck again against a Circus of Bristol Blenheim bombers on November 8, and brought down 14 British pilots for a loss of three of their own. At first, the British thought these new German planes were actually American-made P-36 fighters that the Nazis had captured from their French buyers.

Meanwhile, the Fw-190 made its debut against the Soviets under horrific conditions. The Storm Bird’s mechanical issues combined with the vile Russian winter to render the fighter useless. JG 54’s black men were happy to send their Fw-190s back to France to face Britain’s newest fighter, the Spitfire V.

In February 1942, the German Navy ordered its battlecruisers trapped in Brest, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, to return to the Reich by steaming up the English Channel in Operation Cerberus. This required the Kriegsmarine’s toughest warships to challenge Britain’s channel defenses and the RAF’s main forces. In one of the rare occasions that the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe cooperated closely, JG 26 and its Fw-190s provided close cover for the warships.

The British sent six biplane Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers under Lt. Cdr. Eugene Esmonde, escorted by 11 Spitfires, to attack the German warships. JG 26 pounced on the attack, splashing all the British planes in the channel—only five of 18 British airmen survived. Esmonde was not one of them. He earned a posthumous Victoria Cross, and the German squadron made it home to the Reich.

The British were embarrassed by Germany’s battlewagons succeeding where the Spanish Armada failed, and Galland called Operation Cerberus the high point of his career.

As spring 1942 rose in the West, the Luftwaffe came up with a fighter-bomber model of the Fw-190 that could carry a 500-kilogram bomb into the air. These were used to make retaliatory attacks on England for their bombing raids and rattle British nerves.

To avoid British radar, the Fw-190s of JG 2 and JG 26 made low-level approaches to attack British coastal cities. Leading the attacks were JG 26 aces Major Josef “Pips” Priller and Lieutenant Paul Galland, the CO’s younger brother, who later perished in the war. The offensive saw 775 sorties for a loss of 38 Fw-190s.

On October 31, 1942, 70 Storm Birds carried out the largest Luftwaffe day raid on England since the Battle of Britain, hurling 30 bombs on Canterbury, killing 32 and injuring 116.

The British were forced to resume the wasteful practice of standing patrols over their south coast. They also reacted with more Circus operations. By now, JG 26 was entirely equipped with Fw-190s and doing brilliantly with them. In April, the RAF lost four times as many planes as the Luftwaffe in Circus battles, their Spitfire V aircraft being downed routinely by Fw-190s.

The British were learning how powerful the Storm Birds were the hard way, but on June 23, JG 26’s Lieutenant Armin Faber, got lost. Thinking he was over the English Channel and not the Bristol Channel, he landed his Fw-190 at RAF Pembrey. The RAF quickly moved the plane to the Fighter Development Unit at Farnborough and compared it with the Spitfire V. Britain’s top test pilots soon found that the Fw-190 had superior aileron controls and thus had a superior roll rate to any fighter then in the war—Allied or Axis—and was 25-30 mph faster than Spitfires at altitudes up to 25,000 feet.

Air Marshal Sir William Sholto Douglas, commanding British fighters in southern England, reported to his superiors on July 17, “We are now in a position of inferiority…There is no doubt in my mind, nor in the minds of my fighter pilots, that the FW 190 is the best all-around fighter in the world today.”

However, the RAF tried to come up with better answers. The Hawker Typhoon had structural problems, but the new Spitfire IX proved superior to the Storm Bird at high altitude.

With the American entry into the war, their fighters proved inferior to the Fw-190, including the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the North American P-51A. The former was too heavy in maneuver, and the latter’s Allison engine lacked the power to compete with the Fw-190.

The next big test for the Fw-190 came on August 19, 1942, when the British launched the ill-fated raid on Dieppe. A JG 26 Fw-190 pilot spotted the invasion fleet steaming in, and the squadron was promptly scrambled. The RAF hoped they would gain control of the skies over Western Europe in the assault, and what transpired was the single greatest one-day air battle of the entire war.

The RAF flew 2,617 sorties that day, gaining a clear advantage by 1 p.m., although by then pilots on both sides were flying their third and fourth missions of the day. JG 26 and JG 2’s Fw-190s flew 945 sorties, having a shorter distance to go from their bases to the battlefield.

Under thickening cloud cover, Spitfires fended off Fw-190 attacks and Luftwaffe bombers attempting to attack the landing beaches. The RAF lost 106 aircraft, including 88 Spitfires. The Luftwaffe lost 48 aircraft in the wild battle, but was unable to bring its bombers to bear on the invading ground troops. However, an Fw-190 fighter bomber sank the destroyer HMS Berkeley with a 1,000-kg bomb. Galland and three of his buddies sank another ship with their 20mm guns — a derelict steamer off the Dieppe coast, filling it full of lead until it exploded, to everyone’s surprise.

For the British, there was a lot of finger-pointing and blame evasion in the disaster, but Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, struck an important note in a memo that said, “This bloody affair, though productive of many valuable lessons, ended the summer’s attempt to draw off planes from Russia by trailing Fighter Command’s coast over northern France—a gesture that cost Britain nearly a thousand pilots and aircraft.”

With that, Rhubarbs and Circuses ended and daylight air battles over Europe were turned over to the American “Mighty Eighth” Air Force and its Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, which flew in tight formation at altitudes of 27,000 feet and bristled with .50-caliber machine guns for defense while 8,000-pound bombs devastated Germany’s factories and infrastructure.

Fw-190 “Butcher Bird” pilots found it difficult to make stern, beam, or forward attacks against the formidable B-17 and its machine guns, particularly during the initial short-range Allied raids on Lille, Rennes, Brussels, and the U-boat bases on the Atlantic Coast, within range of their fighter escort. That November, Fw-190s were sent to a newly opened front, Tunisia, where American and British troops were storming toward Tunis and Bizerte. The Americans relied on long-range Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters, which could not maneuver as well as the Fw-190, while the British used Spitfire Vs and IXs, whose operations were hamstrung by the Tunisian winter, which turned their bases into muddy quagmires. In comparison, the Luftwaffe took over concrete airfields around Tunis and Bizerte.

On the Eastern Front, Fw-190s were still flying in limited numbers with JG 54 near Leningrad. Luftwaffe fighters and fighter bombers were acting as a “fire brigade” to assist German ground forces facing increasingly larger and more powerful Soviet troops.

Germans “experten” pilots flew until they were dead or wounded. On the Eastern Front, that meant German aces, facing inferior aircraft like LaGG-5s, MiG-3s, and American Lend-Lease P-39s, racked up more than 100 kills. Top Fw-190 Eastern Front ace Otto Kittel shot down 227 Soviet planes before his death. However, the Luftwaffe only assigned a few hundred Storm Birds to the Eastern Front at any time.

The big battle for the Fw-190 and its new variants was the struggle over the Reich against the Mighty Eighth, whose B-17s and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers were hammering factories by day and the RAF’s Bomber Command’s Avro Lancasters and Handley Page Halifaxes, which pounded whole cities by night.

The Luftwaffe converted a number of Fw-190s into night fighters, using the “Wilde Sau” (Tame Boar) tactic, which meant that they would fly over cities during air raids, without ground control, to attack Allied bombers illuminated by ground fires. Two wings of Fw-190s were assigned to this duty under Colonel Hans-Joachim “Hajo” Herrmann. They were tested right away in July 1943, when the RAF attacked Hamburg using “Window”—metal tinfoil jettisoned from bombers—to blind German radar. Only the Tame Boar fighters could locate the bombers. However, the Tame Boars ran into greater difficulties than that—they were shot at by their own flak and had difficulty landing, leading to crashes.

By day, Fw-190s defending Germany also had a tough time, so Kurt Tank developed new variants of his Storm Bird, giving them armored canopies, 30mm guns, and Werfer-Granate-21 unguided air-to-air rockets to attack bombers. The Fw-190 A8 that resulted was dubbed the “Pulk-Zerstörer” (Bomber-Formation Destroyer). With such heavy loading, this variant of the Storm Bird proved less maneuverable than its predecessors, and it required Me-109 fighter escort when it flew to attack American bombers. However, the Fw-190 A8s performed as planned. They pressed stern attacks to within 100 yards.

Luftwaffe ace Richard Franz said this about his Fw-190: “When we made our attack, we approached from slightly above, then dived, opening fire with 13mm and 20mm guns to knock out the rear gunner and then, at about 150 meters, we tried to engage with the MK 108 30mm cannon, which was a formidable weapon. It could cut the wing off a B-17. Actually, it was still easier to kill a B-24, which was somewhat weaker in respect of fuselage strength and armament. I think we generally had the better armament and ammunition, whereas they had the better aircraft.”

The Americans responded to the Storm Bird by cutting loose long-range P-51 Mustang fighter escorts, powered by British Merlin engines, which could fly all the way to Berlin. Superior in nearly every way to the Fw-190, they drove German fighters from the skies during 1944’s “Big Week.”

JG 26 had its hands full as the Allied invasion of Normandy loomed, with British and American tactical bombers, all heavily escorted by the latest model Spitfires and P-51s, pounded German transportation lines and defenses. The Luftwaffe also continued to use Fw-190s in the fighter bomber role against England.

On D-Day, JG 26, like the rest of the German command, was caught by surprise, and only two pilots were able to respond, Lt. Col. Priller and his wingman, Lieutenant Heinz Wlodarczyk, ordered to strafe the British invasion beaches. They did so. They made one strafing run, then headed back to base, undamaged. Priller survived the war with 101 kills, while Wlodarczyk was killed in Operation Bodenplatte (Baseplate) on New Year’s Day, 1945.

That attack, part of the Battle of the Bulge, marked the real end of the Luftwaffe in the war. The German fighter force was ordered to support the failing Nazi Ardennes offensive by attacking numerous British and American airbases in France, Belgium and The Netherlands at dawn, shooting up aircraft on the ground. Numerous Fw-190s of many types were involved, and while they destroyed or damaged many Allied aircraft—including Field Marshal Montgomery’s personal transport—the Luftwaffe took horrendous losses in planes and pilots. The Germans lost 117 Fw-190s.

The Luftwaffe found yet another role for the versatile Storm Bird with the “Mistel” project in 1945. Fw-190s were attached by struts and control cables to the top of a Junkers Ju-88 bomber, whose cockpit was replaced by explosives. The Fw-190 was to take off, release the Ju-88 near a Soviet bridge over the Oder, and control it in a powered dive on the bridge. The project failed—none were destroyed.

Luftwaffe Captain Hans Linge, who scored 70 kills flying a Storm Bird, said, “I first flew the Fw-190 on 8 November 1942 at Vyaz’ma in the Soviet Union. I was absolutely thrilled. I flew every fighter version of it employed on the Eastern Front. Because of its smaller fuselage, visibility was somewhat better out of the Bf-109. I believe the Fw-190 was more maneuverable than the Messerschmitt—although the latter could make a tighter horizontal turn; if you master the Fw-190 you could pull a lot of Gs (g force) and do just about as well. In terms of control and feel, the 190 was heavier on the stick. Structurally, it was distinctly superior to the Messerschmitt, especially in dives. The radial engine of the Fw-190 was more resistant to enemy fire. Firepower, which varied with the particular series, was fairly even in all German fighters. The central cannon of the Messerschmitt was naturally more accurate, but that was really a meaningful advantage only in fighter-to-fighter combat. The 190’s 30 mm cannon frequently jammed, especially in hard turns—I lost at least six kills this way.”

Of the thousands of Fw-190s in many variations that were produced, about 28 are estimated to survive today, usually as museum exhibits or airbase displays.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments