By Al Hemingway

When visitors gaze upon the immense marble statute of a seated Abraham Lincoln looking out upon the reflecting pool at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., they are naturally overcome with a feeling of awe. When they stroll inside the building itself and read Lincoln’s words, they come away with a sense of enormous admiration for the man who saved the Union and was later gunned down by a Confederate-sympathizing assassin.

However, was Lincoln as popular as we think? Many people today probably believe that he was elected twice to our nation’s highest office by an overwhelming majority. However, as historian Larry Tagg points out in his new book, The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln: The Story of America’s Most Reviled President (Savas Beatie, New York, 2009, 576 pp., photos, index, notes, $32.95, hardcover), such was not the case.

However, was Lincoln as popular as we think? Many people today probably believe that he was elected twice to our nation’s highest office by an overwhelming majority. However, as historian Larry Tagg points out in his new book, The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln: The Story of America’s Most Reviled President (Savas Beatie, New York, 2009, 576 pp., photos, index, notes, $32.95, hardcover), such was not the case.

With the exception of one uneventful term in the House of Representatives, Lincoln had been an obscure frontier lawyer. He did receive notoriety when he openly debated Stephen Douglas for a U.S. Senate seat in Illinois in 1858 and when he delivered his now-famous Cooper Union speech in 1860 warning against “a house divided.” Despite those two noteworthy performances, he still remained relatively unknown nationally.

Lincoln managed to win the 1860 presidential election by a narrow margin when the Democrats split along sectional lines, with Douglas running as a northern candidate and John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky being the southern standard-bearer. Although he managed to squeak out a victory, Lincoln drew slightly less than 40 percent of the popular vote. Only three other major-party candidates have fared worse in two-party elections: Herbert Hoover, Barry Goldwater, and George McGovern. All lost, it should be noted. When it was announced in the newspapers that Lincoln had won, many readers wondered aloud: “Abraham who?”

Lincoln’s election was the final impetus for the Civil War, as southern states dropped out of the Union after he was elected. Ironically, Lincoln was also skewered in many northern newspapers. He was particularly ridiculed for his surreptitious entrance into the capital via Baltimore by night train after rumors arose that he was to be shot along the way. This particular incident so embarrassed Lincoln that he vowed never again to appear to cower to threats.

Many in Washington who considered themselves the upper crust of society were appalled at the new president’s sloppy appearance, uncombed hair, ill-fitting clothes and Midwestern drawl. His penchant for telling corny jokes particularly disgusted the Washingtonian elite.

As the bloody conflict continued, Lincoln was vilified in the North as well as the South. Even his one-time supporter Horace Greeley of the influential New York Tribune had a field day whenever Union forces were whipped on the battlefield. With the exception of some success in the western theater and a few victories in the east, the Union war effort sputtered. Lincoln’s re-election campaign seemed doomed.

That would change when Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman racked up impressive victories in 1864, with Sherman capturing Atlanta mere weeks before the election. Lincoln was re-elected president over Democratic nominee George B. McClellan, a former Union general whom Lincoln had removed from command for insufficient aggressiveness.

Throughout his two terms in office, Lincoln battled not only the Confederacy, but also the Congress, his cabinet and even friends who previously had supported him. One thing cannot be denied—Lincoln was the consummate politician, defusing many crises with an affable demeanor that concealed a steely temperament and an unshakable determination to preserve the Union, no matter what the cost.

When the war finally ended in April 1865, Lincoln girded himself for the next impending struggle—the political reconstruction of the South. Many wanted the Rebels to pay dearly for seceding from the Union, but Lincoln had other ideas. “Let ’em up easy,” he advised. His forgiving attitude toward the southern states infuriated hard-liners, but he was determined to heal the country.

Ultimately, his plans would not be carried out. On Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Lincoln was fatally shot by actor John Wilkes Booth in Ford’s Theater while watching a production of the ridiculous comedy, Our American Cousin. He died the next morning. Thousands lined the 1,600-mile route as his body was brought back by train to his adopted home of Springfield, Illinois, where he was laid to rest.

Abraham Lincoln, the hard-knuckles politician who had ascended to the presidency by a slender margin and was loathed and mocked by many throughout his career, would immediately be transformed a spotless martyr in the eyes of his countrymen. An assassin’s bullet had seen to that.

Gallipoli: The End of the Myth by Robin Prior, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2009, 288 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $35, hardcover.

Gallipoli: The End of the Myth by Robin Prior, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2009, 288 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $35, hardcover.

With Europe in the throes of World War I, fighting on the Western Front in France and Belgium had ground to a standstill by late 1914. Casualties were mounting at an alarming rate, with no obvious military gains of any significance to show for it.

Enter Winston Churchill, Great Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, with a multitude of ideas to break the bloody stalemate. After a series of meetings, he successfully pushed a scheme to bombard forts and destroy large artillery emplacements along the strategically located Gallipoli Peninsula of Turkey, Germany’s partner in the war. To the west of the peninsula lay the Aegean Sea, to the east the Dardanelles Straits.

It was decided the attack would be a strictly seaborne attack conducted by the British Royal Navy, with some assistance from the French. British Secretary of State for War Lord Herbert Kitchener would not release any reserve army troops for fear of needing them in France.

From its inception, the naval campaign was a disaster. In the planning stage, the amount of ammunition needed to obliterate the fortifications and the number of ships involved were badly miscalculated. The mines laid by the Turks were another factor not seriously considered by Churchill and his planners.

In the end, Kitchener was forced to send troops when a land campaign began. Included in this number was a large contingent of Australian and New Zealand (ANZAC) forces. During the subsequent eight months of fighting, from April 1915 to January 1916, thousands of Allied soldiers were killed or wounded in senseless frontal assaults. As with the Western Front, the Gallipoli Peninsula was soaked with the blood of gallant soldiers with no noteworthy advances to show for their loss.

Where does the fault lie for the campaign’s disaster? Certainly, many of the admirals and cabinet members of the British government were to blame, but military historian Robin Prior lays the bulk of the responsibility on Winston Churchill. It was Churchill who “had wanted to attack Turkey ever since it sided with the Axis Powers,” says Prior. He then “bulldozed” the plan “past his naval advisors” and later convinced the Cabinet to adopt it. “These circumstances led to the naval attack and its failure led inexorably to the military campaign,” Prior charges. “Churchill is therefore to blame for the whole sorry fiasco.”

Churchill would resign as First Lord of the Admiralty after the Dardanelles campaign and volunteer to command an army battalion in France before returning to government service later in the war. Even though the Gallipoli debacle was a stain upon his career, the British public would once again call upon the elder statesman to lead the country in yet another world war a quarter century later. Churchill would redeem himself for Gallipoli.

Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas by Benson Bobrick, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 416 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $28.00, hardcover.

Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas by Benson Bobrick, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 416 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $28.00, hardcover.

In his latest offering, popular historian Benson Bobrick attempts to dispel the central myth about Union General George Henry Thomas, who was given the sobriquet “the Rock of Chickamauga” after he defiantly stood his ground against Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s onrushing forces during the height of the battle.

Despite his stand at Chickamauga and his noteworthy successes on other battlefields, Thomas was considered “slow” by many of his fellow officers, including Ulysses S. Grant, who later led Union forces to victory at Chattanooga. Thomas, however, was anything but slow in his tactics. He enjoyed an enviable record of success during the Mexican War as well as the Civil War.

Although a Virginia native, Thomas opted to remain with the Union after the firing on Fort Sumter in 1861. (He had married a New York heiress several years earlier.) This infuriated his family, who turned his picture against the wall, burned his letters and vowed to never speak to him again. Even after the war, when Thomas attempted to reconcile the differences between him and his family, they still refused to acknowledge him.

Grant and Thomas had a similarly rocky relationship. It was Grant who permanently tagged Thomas as being slow in his movements. In his influential memoirs, Grant gave scant praise to his able subordinate. A modest and humble individual himself, Thomas destroyed all his wartime correspondence and, unlike Grant and William T. Sherman, never penned his own side of the story. All he would say was: “I made my army and my army made me.”

Today, historians are looking at Thomas’s contributions in a new light. As Bobrick states in his admittedly partisan book: “The deliberate suppression of his fame by the two best-known soldiers of the Union, Sherman and Grant, is a continuing national tragedy that must be set right. Justice never dies.” Sometimes, it’s just slow.

Marcus Aurelius: A Life by Frank McLynn, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2009, 684 pp., photos, index, notes, $30, hardcover.

Marcus Aurelius: A Life by Frank McLynn, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2009, 684 pp., photos, index, notes, $30, hardcover.

In the nearly 2,000 years since his death, Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius is still considered by many historians to have been one of the wisest and noblest leaders of all time. His book Meditations, which he wrote during one of his military campaigns, is still widely read today. Such leaders as Frederick the Great, English captain John Smith and African dynasty-builder Cecil Rhodes, carried a copy of Aurelius’s book with them wherever they traveled.

Aurelius preached a stoic philosophy and was a staunch advocate of a spiritual lifestyle. His writings were to be the prime resource for his own self-improvement and rational thinking. The personal observations he penned would later enable him to aspire to be a more enlightened emperor.

Although he had a philosophical approach to ruling the Roman Empire, his tenure was racked with war. His military expeditions took him to Asia to do battle against the Parthians and across the Danube to suppress the rebellious Germanic tribes. Despite these distractions, Aurelius continued his philosophical studies.

Aurelius would succumb to the plague in Vienna in ad 180. His passing was marked with much sorrow and now is considered by many the end of the Pax Romana, the period in which the Empire enjoyed its longest stretch of relative tranquility. Little did Aurelius realize that his writings would transcend time and make him one of the greatest philosophers—as well as rulers—of the ancient world.

A Hundred Feet Over Hell: Flying with the Men of the 220th Recon Airplane Company Over I Corps and the DMZ, Vietnam 1968-69 by Jim Hooper, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 258 pp., photo, index, $25, hardcover.

A Hundred Feet Over Hell: Flying with the Men of the 220th Recon Airplane Company Over I Corps and the DMZ, Vietnam 1968-69 by Jim Hooper, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 258 pp., photo, index, $25, hardcover.

Ask any grunt in Vietnam, whether he be Army or Marine, and he will tell you that air support was vital in keeping the enemy at bay. Many battles were won when American aircraft, referred to as “fast movers,” would swing in low and drop their ordnance or napalm, often inciting cheers from the “ground-pounders” observing the action.

To achieve maximum accuracy, pilots known as FOs, or forward observers, would fly at extremely low altitudes in small Cessna O-1 planes called “Bird Dogs” to observe enemy movements and relay their findings back to the Direct Air Support Center. These brave individuals did a remarkable job under extremely trying circumstances to deliver much-needed air support to those on the ground.

Former FO Jim Hooper has written a gutsy account of his time in Vietnam. His area of operations was in the northernmost section of the country called I Corps. There, he dodged Communist antiaircraft and rifle fire, but also rifle fire. His unit, given the nickname “The Catkillers,” did an extraordinary job at controlling air strikes for both Marine and Army outfits combating North Vietnamese Army forces crossing into South Vietnam via the Demilitarized Zone.

An interesting addition to the book is the epilogue explaining what became of each pilot after his return stateside. Each individual has enjoyed great success in his respective endeavors, and many have commented how rewarding their tour of duty was with the Catkillers. The positive remarks by these Vietnam veterans help combat the perpetual myth that all who served there came home either a drug addict or a crazed killer. Hooper deserves a big thank you from Vietnam vets for writing this book and relating how he and his fellow pilots served honorably during that unpopular conflict.

American Heroes: Profiles of Men and Women Who Shaped Early America by Edmund S. Morgan, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2009, 278 pp., index, $27.95, hardcover.

American Heroes: Profiles of Men and Women Who Shaped Early America by Edmund S. Morgan, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2009, 278 pp., index, $27.95, hardcover.

Celebrated historian Edmund S. Morgan has written a lively and authoritative book on individuals who helped transform colonial America into the nation we have today. He discusses the usual figures that contributed greatly to this effort, men such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and William Penn. He quotes from Poor Richard’s Almanac, Franklin’s annual newspaper published, concerning the evils of a hero. “There are three great destroyers of mankind,” Franklin wrote, “Plague, Famine and Hero. Plague and Famine destroy your persons only, and leave your goods to your Heirs; but Hero, when he comes, takes life and goods together; his business and glory it is, to destroy man and the works of man. Hero, therefore, is the worst of the three.”

Despite Franklin’s denunciation of heroes, Morgan still uses the term when discussing those he believes live up to the name. Two such individuals, Giles Cory and Mary Easty, were accused of witchcraft and executed in Salem, Mass., in 1692. Instead of being intimidated by the magistrates, they steadfastly refused at their trial to condemn any others for the same “crime.” Their courage was the impetus for the reversal of the sentences by the General Court of Massachusetts in 1697. Although this could not bring back those innocent people who already had been put to death, it served as a valuable lesson not to succumb to mass hysteria in such matters.

Morgan’s very readable account of those early pioneers who shaped this land is enlightening. By examining those who came to these shores to escape persecution they endured in the native lands, Morgan has shed new light on early American history and its heroes.

A More Unbending Battle: The Harlem Hellfighters’ Struggle for Freedom in WWI and Equality at Home by Peter N. Nelson, Basic Civitas Books, New York, 2009, 291 pp., index, $27.50, hardcover.

A More Unbending Battle: The Harlem Hellfighters’ Struggle for Freedom in WWI and Equality at Home by Peter N. Nelson, Basic Civitas Books, New York, 2009, 291 pp., index, $27.50, hardcover.

Originally organized as the 15th Infantry Regiment out of New York, the all-black unit was reformed in the spring of 1918 as the 369th Infantry Regiment. Because of segregation the new outfit, nicknamed “The Harlem Hellfighters,” was assigned to the French Army. On the battlefield the soldiers performed admirably, participating in the Champagne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, Champagne and Alsace campaigns. Many of its members were highly decorated by both the American and French governments.

It was their bitter struggle for racial equality once they returned home from the war that the author concentrates on. After witnessing horrific combat on the French killing fields, many Hellfighters adamantly refused to be treated as second-class citizens by a country that had sent them off to fight.

Nelson refers to this as the emergence of the “New Negro,” who would not endure disrespect or have to live in a “Jim Crow” society where African-Americans were considered equal, but separate. This sparked deadly riots throughout the country, resulting in numerous injuries and deaths among whites and blacks. One all-black town, Rosewood, Florida, was burned to the ground after a white woman falsely accused a black stranger of assaulting her.

It took years before the Civil Rights Act became the law of the United States. Those who had fought in the “war to end all wars” deserve praise for their important role in bringing to light the unfair treatment of blacks in the country at that time. “What the pessimists underestimated was the fight in the men who went away and returned,” Nelson writes, “as well as the pride they would inspire, without which neither battle could be won, the one in France or the one back home.”

American Commando: Evans Carlson, His WWII Marine Raiders, and America’s First Special Forces Mission by John Wukovits, NAL Caliber Books, 2009, 337 pp., photos, index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

American Commando: Evans Carlson, His WWII Marine Raiders, and America’s First Special Forces Mission by John Wukovits, NAL Caliber Books, 2009, 337 pp., photos, index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

Evans Carlson certainly did not fit the poster image of a United States Marine. The tall, lanky, fragile-looking New Yorker nonetheless thirsted for action and adventure. He enlisted in the U.S. Army prior to World War I and was commissioned a second lieutenant, seeing service in the Philippines and Hawaii but missing the war in France.

Carlson left the Army but enlisted in the Marines a few years later after becoming bored with civilian life. His subsequent service in Nicaragua in the 1930s, where he led native National Guard soldiers against Communist forces led by Augusto Cesar Sandino, honed his small-unit tactical skills, which he would use in World War II against the Japanese. His Marine Raider unit would embark on America’s first special forces-type action, when they surprised the Japanese on Makin Island in August 1942. The leathernecks destroyed Japanese installations, gathered intelligence on the Gilbert Islands and help divert enemy attention from the amphibious landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

In the fall of 1942, Carlson’s 2nd Marine Raider Battalion conducted a long-range reconnaissance behind enemy lines, called “The Long Patrol” by historians, on the island of Guadalcanal. It was very successful, and proved that guerrilla-style tactics could be used successfully by American troops.

Many of his contemporaries, however, distrusted Carlson. He had spent considerable time with the Chinese Communists during his tenure in that country and became friends with Mao Zedong. He resigned his commission in the late 1930s but was reinstated after the attack on Pearl Harbor, much to the dismay of his peers.

Today, many of Carlson’s ideas, deemed unorthodox during World War II, are used by Special Forces units. He took the Chinese phrase “Gung Ho,” which means “to work together,” as the motto for his unit. Considered by many a maverick, Carlson’s courage under fire cannot be questioned. He passed down his leadership traits to his junior officers, who became fine leaders in their own right. Carlson and his elite Marine Raiders remain legendary in the annals of Marine Corps history.

Soldier of the Press: Covering the Front in Europe and North Africa, 1936-1943 by Henry T. Gorrell, edited with an Introduction by Kenneth Gorrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 2009, 320 pp., photos, maps, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Soldier of the Press: Covering the Front in Europe and North Africa, 1936-1943 by Henry T. Gorrell, edited with an Introduction by Kenneth Gorrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 2009, 320 pp., photos, maps, index, $34.95, hardcover.

When Kenneth Gorrell discovered a long-lost typed manuscript vividly describing his relative Henry “Hank” Gorrell’s experiences as a war correspondent in Europe, he unearthed a real treasure. Gorrell was in Italy and Spain prior to the United States entering the conflict. His dispatches, written with honesty and clarity, often got him into serious trouble with the governments he was reporting about.

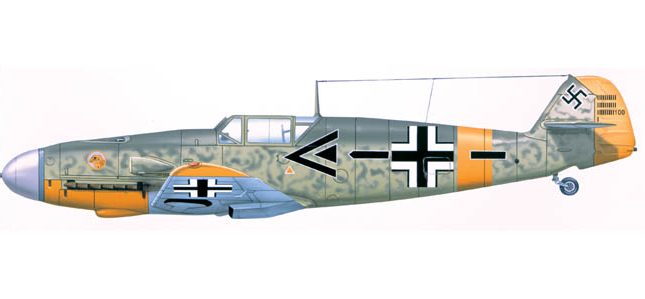

After Gorrell was ousted from Italy by the Mussolini regime, he traveled to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War. It was Gorrell who first reported the Nazi and Fascist intervention during that conflict. Spain became a killing ground in which new tactics such as the German blitzkrieg were being tested.

Gorrell later made headlines with his eyewitness accounts of the fighting in the Balkans, Romania and Albania, which often received scant attention in the American press. After the United States declared war on the Axis Powers after Pearl Harbor, the reporter was on the frontlines with American forces in Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Landing on Utah Beach on D-Day, Gorrell delivered the first reports of the fighting there by utilizing a radio transmitter with its antenna hanging from a tree.

Kenneth Gorrell deserves kudos for finding this gem in an old trunk in an attic in New Hampshire and thus ensuring that his relative’s work was finally published. After more than six decades, Hank Gorrell’s story can finally be told.

Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945 by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 324 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $34.95, hardcover.

Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945 by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 324 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $34.95, hardcover.

The Mediterranean Sea saw more naval action during World War II than both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans combined. The author sets out to put to rest once and for all the notion that the Italian Navy did not perform well. Nothing could be further from the truth, in O’Hara’s opinion.

O’Hara rejects the claims by Great Britain and Germany that they took part in all the major naval actions in the Mediterranean. “In fact, however, a dispassionate survey of the Mediterranean campaign supports the opposite conclusions: the Italian navy fought hard; it often fought very well; and it accomplished its major objectives,” writes O’Hara. “It kept Italy’s African and Balkan armies supplied for three years and largely controlled the central Mediterranean.”

O’Hara’s book allows the reader to form a complete understanding of the extreme importance of the Mediterranean Sea. By war’s end, the American fleet had emerged as the dominant force on that body of water—a role it has not relinquished to this day.

On the Western Front with the Rainbow Division: A World War I Diary by Vernon E. Kniptash, edited by E. Bruce Gelhoed, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2009, 236 pp., photos, maps, index, $29.95, hardcover.

On the Western Front with the Rainbow Division: A World War I Diary by Vernon E. Kniptash, edited by E. Bruce Gelhoed, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2009, 236 pp., photos, maps, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Vernon E. Kniptash was an eager enlistee when the U.S. was dragged into World War I in April 1917. Europe had already been bludgeoned by fighting since August 1914 and the arrival of fresh troops on the battlefield was a welcome sight for the Allies.

After enlisting in the U.S. Army, Kniptash joined his unit, the 150th Field Artillery of the famed 42nd Infantry Division, commonly referred to as the “Rainbow Division.” As a radio operator, Kniptash had access to information occurring as it happened. He kept a journal for two years describing his experiences in France. Most of what he wrote was spontaneous, giving his prose a concise and sincere effect as he described the great historical events unfolding around him.

War diaries such as the one Kniptash wrote, enable historians and readers to gain significant insights into history. Young and innocent at the beginning of the war, Kniptash describes soldier’s transformation from raw recruit to hardened combat veteran. He was lucky enough to have survived the conflict. He returned home to Indianapolis to begin anew and try to forget the carnage and horror he had witnessed. It is appropriate that the last word he wrote in his diary was “finis.” The war was indeed finished and Vernon Kniptash was embarking on a new phase of his life.

No Peace for the Wicked: Northern Protestant Soldiers and the American Civil War by David Rolfs, The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 2009, 283 pp., notes, index, $38.95, hardcover.

No Peace for the Wicked: Northern Protestant Soldiers and the American Civil War by David Rolfs, The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 2009, 283 pp., notes, index, $38.95, hardcover.

It is difficult when serving during time of war to rationalize taking another human being’s life. Most Americans on both sides during the Civil War had a religious upbringing that was in direct conflict with this belief. Nevertheless, the majority of soldiers on both sides performed their duty believing that their cause was righteous and that God was on their side.

The author examines the Northern Protestant soldier during the conflict to explain how the young men justified their actions and remained dedicated to fighting and preserving the Union. He points out that Northern churches were quick to maintain that Union soldiers were being used by God as “the instruments of His judgment.”

Destined to be “soldiers of Christ,” says Rolfs, the Union soldiers donned their uniforms to do battle with the godless men of the Confederacy. Likewise, their counterparts took up arms to repel the satanic hordes invading Dixie from the north. Although simplistic, such views enabled soldiers on each side to function in that cruel and unforgiving crucible known as war.

The United States Army in the War of 1812: Concise Biographies of Commanders and Operational Histories of Regiments, with Bibliographies of Published and Primary Sources by John C. Fredriksen, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2009, 311 pp., photos, index, $45, softcover.

The United States Army in the War of 1812: Concise Biographies of Commanders and Operational Histories of Regiments, with Bibliographies of Published and Primary Sources by John C. Fredriksen, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2009, 311 pp., photos, index, $45, softcover.

They were known as “Mr. Madison’s Warriors,” referring to our nation’s fourth president, these soldiers who once again had to battle the world’s best army at that time in the War of 1812. As the author states, very little has been written about our armed forces during this turbulent era in America’s history.

Although the U.S. Army suffered serious setbacks during the conflict, they still emerged as a viable fighting force. The senior officer corps, described by the author as “ossified,” did produce some shining stars on the field of battle—Jacob J. Brown, Winfield Scott and the legendary Andrew Jackson, to name three. It was during the period between the War of 1812 and the Mexican War of 1846-48 that the military establishment had a chance to grow and mature.

Fredriksen devoted more than 30 years of research to his book. In doing so, he has compiled an extensive amount of information on the war, its leaders (both military and civilian) and the units involved. His account is a tribute to the memories of those who fought in that truly forgotten war.

The Maps of First Bull Run: An Atlas of the First Bull Run (Manassas) campaign, excluding the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, June–October 1861 by Bradley M. Gottfried, Savas Beatie, New York, 2009, 134 pp., maps, appendix, $34,95, Hardcover.

The Maps of First Bull Run: An Atlas of the First Bull Run (Manassas) campaign, excluding the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, June–October 1861 by Bradley M. Gottfried, Savas Beatie, New York, 2009, 134 pp., maps, appendix, $34,95, Hardcover.

Here is another fine offering in the publisher’s Military Atlas Series, one that concentrates on the action during the First Battle of Bull Run, or Manassas, in June 1861. Fifty-one maps are included in the book that detail both Union and Confederate troop movements. A legend has been added to each map illustrating terrain features such as woods, orchards and ridges, so that readers can easily follow the tactics employed during the battle.

Each map is preceded by a brief overview of the events leading up to the fighting and the actual campaign itself. The author has included an appendix in the back of the book listing all the units involved and the casualties sustained by each of them. “I am optimistic that readers who approach the subject with a higher level of expertise will find the maps and text not only interesting to study and read, but helpful,” Gottfried writes.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments