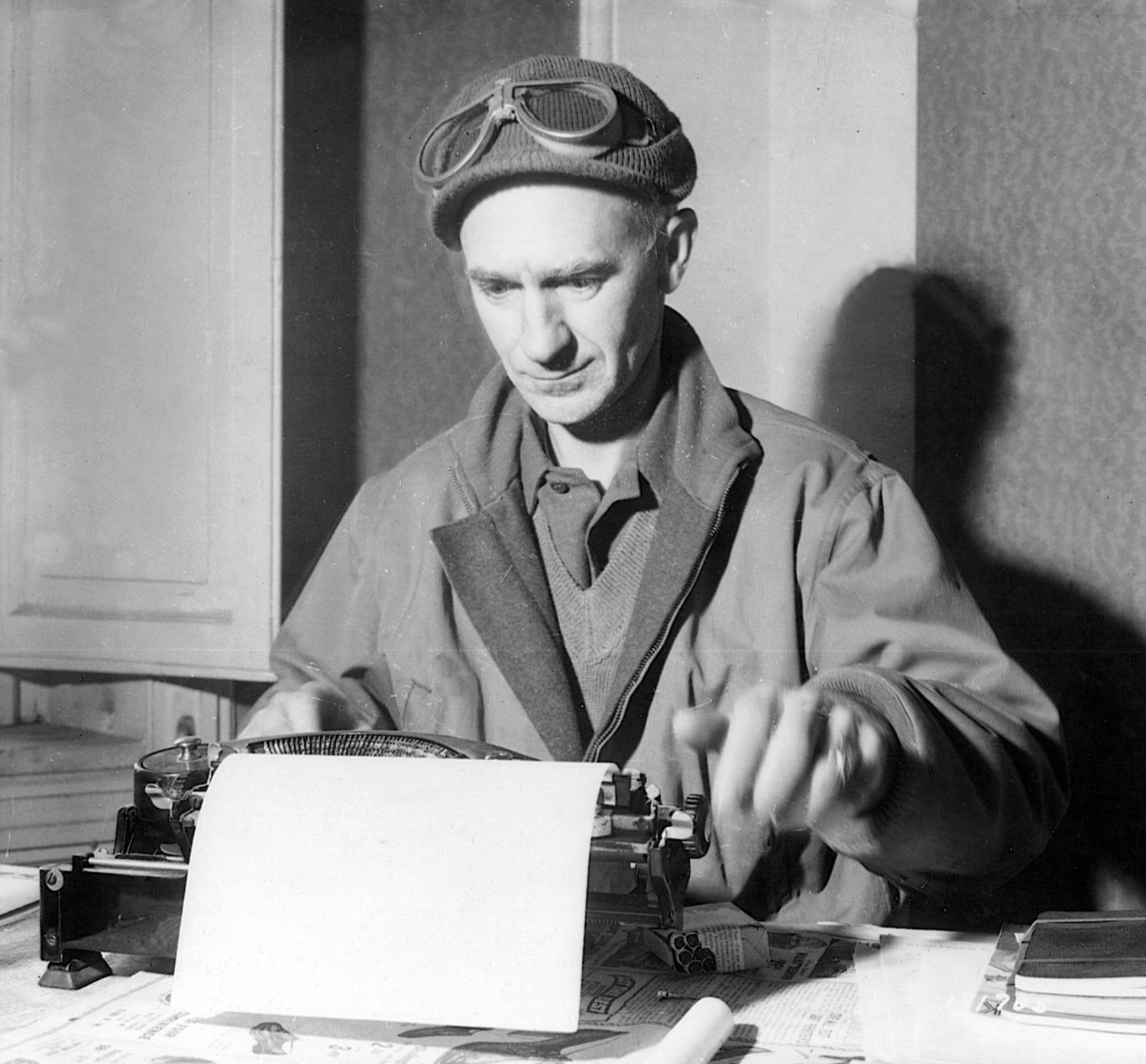

By Robert A. Rosenthal

The tranquility of early dawn on June 15, 1944, was interrupted by the sounds of powerful naval guns and the roar of amtraks churning the water. The invasion of Saipan had begun.

Two days earlier a U.S. Navy bombardment fleet consisting of 10 battleships, 11 cruisers, 15 aircraft carriers, and 26 destroyers had begun bombing and shelling this island night and day. Saipan, a small island in the Marianas group, seemingly had few defenders. It was predicted to be a three-day battle with minimal casualties. So how did this conflict turn into the bloodiest battle in the Pacific War to date? And why did the American invaders suffer more than 16,000 dead and wounded against their tenacious Japanese enemy?

By the summer of 1944, the war was not going well for Japan. The Japanese Empire was a remnant of its former glory. Its Pacific possessions were lost to the aggressive U.S. island hopping strategy. Its forces in China were mired in prolonged fighting with Communist forces and the National Chinese Kuomintang. Its armies in Burma were being pushed back by the advancing British and Indian troops. Even its home islands of Honshu and Kyushu were subjected to frequent American bombing raids that killed of thousands of civilians in a single attack.

The situation was desperate, and the Japanese general staff knew that they could not win the war; the issue was accepting the terms of defeat. The Allies made their goal very clear in the Potsdam Declaration: “unconditional surrender.” The terms of this pronouncement were unpopular with Japanese military and civilian officials, who attempted to find some way of mitigating the onerous provisions, especially those concerning the future of the monarchy, Allied occupation, disarmament, and war crimes trials. They thought that if they ferociously defended the home islands, the United States would suffer such huge casualties that the American will to continue fighting would diminish and a negotiated peace could be attained. This strategy guided the actions of Lt. Gen. Saito Yoshitsugu in formulating his defense of Saipan.

Saipan measures 14 miles long by five miles wide across its center and is irregularly shaped. Unlike other mid-Pacific island conquests earlier in World War II, which were fought on atolls, flat, low-lying coral reefs, Saipan is covered with rugged hills and ridges and is dominated by the 1,600-foot Mount Tapotchau. This afforded defenders the advantage of high ground and the ability to build caves and redoubts for gun emplacements, many of which were located on the reverse slopes of the hills and were therefore impervious to naval gunfire.

Naval guns are designed to fire with a flat trajectory and were ineffective against these dug-in positions. Furthermore, the battleships fired from more than 10,000 yards (almost six miles) from shore since they did not want to risk sailing into shallow waters that had not yet been swept for mines. It is estimated that during the two-day naval bombardment 12,000 tons of naval ordnance were fired but did little to soften up Japanese pillboxes by the time the Marines landed.

Added to this disadvantage, coral barrier reefs surrounded most of the good landing beaches. Unbelievably, U.S. military intelligence did not accurately predict the tides, so many landing craft grounded on the reefs, resulting in the Marines walking ashore in chest-deep water under deadly enemy fire.

The assault began with the landing of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions commanded by Marine Maj. Gen. Holland Smith, followed the next day by the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division led by Army Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith. All of the 64,000 U.S. forces were under the command of Holland Smith. This command arrangement, placing the Marine Holland Smith above the soldier Ralph Smith, would be a source of predictable tension. Nine days after the U.S. troops landed, Holland Smith relieved Ralph Smith of his command in an unprecedented and controversial decision based on Ralph Smith’s apparent “lack of aggressive spirit.”

The two Smiths could not have been more different from each other. Holland, who earned the nickname, “Howlin Mad,” was a cigar-chomping, controversial character with a short temper who always seemed angry. However, he prided himself on his ability to relate to the common Marine. Ralph had been taught to fly by Orville Wright and received the 13th pilot’s license issued with Wright’s signature. He had a calm demeanor and was respected by his fellow officers and his subordinates. He was fluent in French and was awarded two Silver Stars for bravery in World War l.

Central to this conflict between the Smiths were differing tactical perspectives. By instinct and training, the Marines relied on energetic, rapid, and aggressive attacks. In contrast, the Army would take ground gradually with attacks supported by massed artillery bombardment. While these tactics may be suited to the clash of large armies on Continental battlefields, they were less effective against small enemy units dug into irregular positions in the rocky heights of a coral island.

Total Japanese strength on Saipan under General Yoshitsugu included about 32,000 Army troops plus 6,700 naval troops. The island is located 1,500 nautical miles from Tokyo. Although the United States did not have an airplane with that range, prototypes of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber, with a range of 3,500 miles, were currently under development. It is uncertain whether this was known by Japanese military planners, but they feared that the fall of Saipan would provide a base in the Marianas for unstoppable bombing of Japan’s home islands. Some cabinet ministers predicted that the loss of Saipan would mark the beginning of their defeat. Therefore, all means possible were to be employed to prevent this from occurring.

The Bushido Code of moral principles that the Samurai were required to observe remained central to Japanese military life. It developed in the 9th century and stressed frugality, loyalty, mastery of martial arts, and honor unto death. The results of this philosophy can be seen by contrasting the number of captured troops of Nazi Germany with those of Imperial Japan. Throughout the war, Germany fielded 18.2 million troops with 11.1 million captured as prisoners of war—a capture rate of 61 percent. Japan’s forces totaled 8.4 million troops, but only 40,000 were captured—a capture rate of only half of one percent.

By the night of July 6, the battle for Saipan had been raging for three weeks in 90-degree heat with 80 percent humidity, but there was a sense of euphoria among the American troops. Many believed that the main body of the Japanese on Saipan had been destroyed and that only mop-up operations remained to be completed. The Marines began to withdraw from the front lines and, for the first time since the invasion began, there were no overnight artillery fire or starburst shells that lit up the battlefield like daylight. U.S. intelligence reports indicated that the enemy had been reduced to a small force with serious shortages of food, water, small arms, and ammunition that was incapable of initiating or defending against an assault. Unfortunately, this overconfidence was misguided, and the intelligence was wrong.

Japanese forces had been driven into the northern end of the island near Marpi Point, where General Yoshitsugu formulated a plan to assemble every possible unit for a “Gyokusai” attack. Gyokusai or “shattered jewels” defines a conflict in which the combatants condemn themselves to a fight to the death. Only the emperor can declare a Gyokusai, which is a deeply felt notion that in the final battle to death one joins in a form of collective beauty of national destiny by shattering oneself like a beautiful jewel. In true Bushido tradition, each soldier in a Gyokusai knows that he will die a hero’s death and will go directly to heaven. Since supposedly only the emperor could declare a Gyokusai, it is uncertain whether Yoshitsugu actually received word from the emperor. The effect was the same, however. He commanded each soldier to kill seven American devils before he sacrificed himself. In the event, the Japanese troops fought with ferocity unseen before this time.

Yoshitsugu also ordered that all wounded soldiers who were unable to walk be killed or commit suicide using a grenade. Those who were able to walk were armed with whatever weapons were available. There were not enough rifles or machine guns, so many were given hunting knives or daggers. Officers gave away their sidearms and kept only their sabers. When these gave out, the men cut bamboo poles and sharpened the ends. Evidence discovered after the attack showed that many of the estimated 3,000 attackers, especially the civilian construction workers, had consumed large quantities of saké, Japanese rice wine, and beer before launching the attack and were drunk when they died.

The charge began under a full moon shortly before midnight on July 6. Marine observers watching the attack through field glasses witnessed a strange phenomenon. Behind the enemy assault formations was a weird, almost unbelievable procession of the lame and the blind—the sick and wounded from the field hospitals had come forth to die. Bandaged men, amputees, men on crutches, and walking wounded were helping each other along. Some were armed; some carried only a bayonet lashed to a long pole or a few grenades. Many had no weapons of any type. If they could kill a few Americans, they would be happy, but their main objective was to die in battle in the service of their emperor.

The tradition of death instead of defeat, capture, and perceived shame was deeply entrenched in Japanese military culture. It was one of the primary traditions of the Samurai life and the Bushido Code. As it became clear that Japan’s capacity to wage war was decreasing and that defeat was inevitable, the military turned to suicide tactics—first with Gyokusai attacks and then three months later, in October 1944, with kamikaze planes and human torpedoes.

The noise of the approaching attack was described as a buzz like a big hive of bees. It kept getter louder and louder and then began to sound like Indian war cries. All at once thousands of Japanese troops burst through American lines. It was reminiscent of a crowd leaving a stadium—pushing and shoving and shouting. Defying machine-gun fire, officers led suicide charges brandishing their swords. The Japanese took fearful casualties but kept coming. On the front line the scene was chaotic, and the fighting was furious. The Japanese rolled over American positions like a tidal wave.

The fighting lasted through most of the day, but by early afternoon the Japanese attack had begun to taper off, simply because the number of soldiers still alive were fewer and fewer with each passing hour. By afternoon of the next day, the 2nd Marines took the airstrip at Marpi Point, cleared the island’s northern sector, and declared Saipan secure. Thus ended the largest Japanese banzai attack in the Pacific War.

What was predicted to be a three-day battle became the biggest and bloodiest struggle in the Pacific War to date. It lasted for 31/2 weeks and resulted in 16,400 American troops dead and wounded, 30,000 Japanese soldiers dead, and an estimated 22,000 civilian casualties. It is not known how many of these casualties occurred during the two-day Gyokusai. Although the battle for Saipan was over, the slaughter was not.

Saipan was the first island encountered by the Americans where there was a large civilian population of indigenous Chamorro, Okinawan workers, and Japanese civilians. Frightened by government propaganda that American soldiers would rape Japanese women and kill their children and urged on by the Japanese military, they refused to give up and chose suicide over surrender. The Chamorros, who are mainly members of the Roman Catholic Church, which considers suicide a mortal sin, did not participate in this flurry of suicides.

Despite appeals in Japanese broadcast over loudspeakers, American troops watched in horror as hundreds of civilians made their way to the top of the 800-foot cliffs and jumped to the rocks below. Others leaped from the cliffs at Marpi Point. At times the water below the point was so thick with the floating bodies of men, women, and children that naval craft were unable to steer a course without running over them. Some individuals bent on suicide simply waded into the surf to drown, while others blew themselves and their families apart with hand grenades.

The invasion of the neighboring island of Tinian began on July 24. Two days earlier, the island was bombed by planes from Aslito Field on Saipan. The first napalm bombs used in the Pacific War were dropped on Japanese positions during the preinvasion softening up of Tinian.

From the beginning the necessity of seizing Tinian, three miles south of Saipan, was understood. There would be a constant threat of raids and artillery attacks on Saipan from the 9,000-man Japanese garrison if not eliminated. The island was also needed for additional air bases. Saipan and Guam alone were insufficient to accommodate the projected bomber fleet and its massive support infrastructure. Also, there were two existing airfields on Tinian that could be improved, eliminating the requirement to build new ones.

Although there was no question about neutralizing Japanese forces on Tinian, the issue was how could it be done quickly and with minimal casualties. There were three possible beaches that landing craft could access.

The obvious landing beach was the wide, white sand strand in front of Tinian Town, where the Japanese had constructed formidable defenses. The next best was on the east side of the island at Asiga Bay, but the prevailing winds could make landings difficult. The least likely sites were located on the northwest coast and designated by the Marines as White One and White Two. Unfortunately, these beaches were narrow—only 60 yards long and 160 yards wide. It was questionable whether a division with more than 12,000 men, supporting units, and equipment could land on such narrow beaches. Heated arguments ensued between General Holland Smith and Admiral Turner, whose job it was to deliver the ground forces to the beach.

Given these constraints, a unique strategy was devised. At dawn on July 24, the 2nd Marine Division staged a fake assault on the broad beach at Tinian Town. Simultaneous with this feint, the 4th Marine Division began landing at the White beaches. By sundown, all nine battalions of the 4th Division and more than 15,000 men were ashore. On August 1 the island was pronounced secure. Four months later, the North Field runways were operational, and the B-29s of the 313th Bomb Wing, under the command of General Curtis LeMay, had begun arriving.

As they did on Saipan, Japanese and Okinawan civilians crawled out of their hiding places and jumped into the sea as the Americans watched in shock. Those who refused to jump were shot by Japanese soldiers before committing suicide themselves.

The battles for the Marianas demonstrated the Japanese military’s total disregard for human death and suffering. This fanaticism would not be forgotten, and 12 months later it would shape the U.S. decision to use the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki rather than invade the Japanese home islands.

For more than 50 years, Bob Rosenthal was an architect specializing in the design and development of health care facilities. Today he is an independent filmmaker whose current project is a documentary about the end of WW II in the Pacific that was principally filmed on Tinian Island. He lives with his wife in Del Mar, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments