By Terry Gore

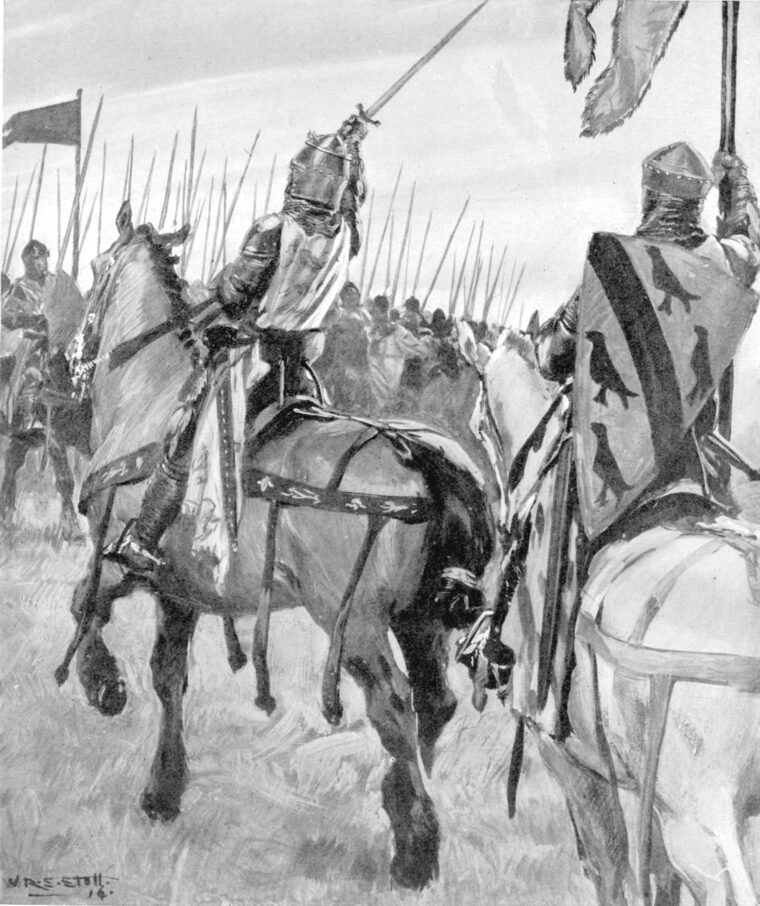

Royalist knights under the command of Prince Edward of England rode with furious speed toward the thousands of London militia who had been sent to set fire to the town of Lewes. The militia was not expecting a ferocious attack by the mounted knights. Their commanding general, Simon de Montfort, did not expect them to hold for long, if at all. But surprisingly, his face did not betray any sign of worry or fear at the prospect of over half his army being ridden down and destroyed. In fact, this was part of his battle plan, one born of desperation and need in order to bring him ultimate victory over his archenemy and onetime close friend, 49-year-old King Henry III of England. The ensuing battle would decide whether the so-called Barons’ War would end in ignominious destruction for Simon and his rebellious lords or be fought to a favorable conclusion for him and his faction. The Battle of Lewes was about to begin.

The ferment of the Barons’ War began back in 1215, when England’s nobility forced a reluctant King John to sign the Magna Carta, pledging to uphold the rights of his barons. An alliance of these barons, nobles, town leaders, and the Church had made such an occurrence a reality, and the Magna Carta permitted the nobles to have a parliament with which to secure their rights from royal whim. But after King John’s death in 1216, his 1-year-old son became King Henry III (1216-1272), and what followed was what historians Ernest and Trevor Dupuy called “a period of inept rule both before and after [Henry came] of age.”

As he grew to manhood, the young king was not without his positive attributes, however. He successfully fought and defeated the Welsh and managed to retain control of his own royal castles, not an easy task in a nation still finding its way a century and a half after the Norman Conquest. Still, he was young and headstrong, described by Tufton Beamish as “impatient, restless and hot-tempered … fussy rather than businesslike, learned rather than clever [and] he forgot his promises as soon as made.” This was not the kind of ruler to win confidence. As the years passed, Henry’s failure to inspire, and his burgeoning fiscal inefficiencies, became more and more apparent to his subjects.

In contrast was one of the most charismatic figures of the period, Simon de Montfort of France. Born in 1208, Simon was the third son of the same-named Albigensian Crusader and victor of the Battle of Muret in 1213. Young Simon was known as a man “brutal in discipline, of an indomitable physical intensity … his fierce insistence upon religion in his forces … all merging in fanaticism [and this] made him in particular a leader of cavalry.” William of Rishanger called him “indeed a mighty man, and prudent, and circumspect; in the use of arms and experience of warfare, superior to all others of his time.”

Simon did not have a great opinion of the English, however. He is quoted as saying of them, “I have been in many lands and among many nations, pagan and Christian; but in no race have ever found such faithlessness and deceit.” Although of French lineage, the de Montfort family held lands in England, a not uncommon occurrence in the 12th and 13th centuries. But King John had confiscated the de Montfort English holdings and doled them out to his favorites. Simon, now head of the de Montfort family, wanted the confiscated lands returned, but the powerful Earl of Chester held them. Simon met with the old earl and persuaded him through force of personality and strength of will to return the lands. As Simon noted, “I had more right than he to my father’s inheritance.” In 1229, Simon traveled to the English court and asked young King Henry to grant the lands back to him. Amazingly, two years later they were his.

The English monarch and the new earl became friends. Why not, as Simon was French, not English, and Henry had little of the English about him. It did not take long for Simon to become High Steward of England. This emboldened him to secretly marry Henry’s sister, Eleanor, the 23-year-old widow of William Marshal. But this secret marriage destroyed the friendship between the two young men because Henry saw it as nothing less than an opportunistic act by de Montfort to set himself closer to the throne of England.

Simon and his new wife traveled to Italy shortly after the ceremony to have the marriage blessed by the Pope, and while there the young earl campaigned with King Frederick II, gaining valuable strategic and tactical expertise on the battlefield. Returning to England, Simon found that Henry felt his trust had been betrayed, and a growing enmity put the two friends on a collision course.

In 1239, Henry publicly attacked Simon and Eleanor de Montfort, who feared for their safety and fled to France. Simon subsequently went on a crusade to the Levant, and in 1241 the nobles in Jerusalem sent word to Frederick II asking that Simon be made regent of the Holy City. Simon refused, however, and returned with his wife to England. Henry welcomed them, but by then Simon had grown mistrustful of the monarch. Nevertheless, Simon and Eleanor named one of their sons Henry, and tensions seemed to ease for a time.

In 1250, King Henry saw to it that his brother, Richard of Cornwall, was elected King of the Romans (Germans). He next wanted his son Edmund to wear the crown of Sicily. This quest for familial power cut more and more into the resources of England because each endeavor required that money be shipped to Rome to curry Papal favor. This vast and seemingly never-ending outlay angered English nobles and subjects alike, because they saw the wealth of their land going abroad while conditions at home became tougher and taxes rose.

Meanwhile, the King of France offered Simon the office of High Steward of France, but Simon, still loyal to his brother-in-law Henry, refused the honor. The French, according to Matthew Paris, favored Simon because, “they knew that he, like his father Simon who had fought for the Church against the Albigenses, had from of old a genuine affection for the kingdom of the French, nor was he a stranger to the French in blood.” Meanwhile Henry continued to borrow and beg for funds, while he jealously began to undermine Simon’s growing prestige and power in England and abroad.

The worsening political situation in England found the inhabitants of London ever less-than-enthusiastic supporters of the King, calling him “mad” and complaining to their local leaders. The Londoners finally got a meeting called in 1253 between Henry, his nobles, and the clergy. But Henry, instead of offering any real solution or compromise, instead called for a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, really a ruse to dispel the rising forces against him. Discussion lasted two weeks, with the nobles, rather than Henry, gaining control of the funds to be raised for the pilgrimage. They did not trust that Henry would use the funds as directed. Distrust and anger between the nobles and the King were endemic and would only worsen.

By 1257, the situation had become even more desperate. Henry wasted money in the failed attempt to have Edmund crowned King of Sicily. He fought a useless war of stalemated attrition against the upstart Welsh and saw a famine ravage the land—London alone suffering a reported 15,000 dead. To alleviate the famine, corn had been brought in from Germany, but Henry confiscated it and sold it at inflated prices to his subjects in order to enrich himself. The nobles had seen enough.

The next year, thanks to royal excess and the influence of King Henry’s French in-laws, the hated Lusignan family, the English barons met at Oxford and wrote the Provisions of Oxford. According to the Chronicle of Aubrey de Trois-Fontaines, the nobles “confirmed the design which they had conceived, that neither for life, death, or holdings, for hatred or for love, or for any cause whatever, would they be bent or weakened in their intent to regain praiseworthy laws, and to cleanse from foreignors this kingdom which is the native land of men of noble birth, and of their ancestors.”

But a short two years later, in 1260, the solidarity the barons had shown at Oxford fragmented. There were many reasons for this, not least of which was Henry’s patent currying of certain nobles’ favor. When Henry felt he had the strength in arms and baronial support to do so, he unilaterally repudiated the Provisions. Now his many “contributions” to Rome paid off. A Papal bull issued that year officially voided Henry’s oath to support the Provisions.

After new negotiations with the King failed to reach a compromise in 1263, those barons still pledged to the Provisions gathered an army and marched from stronghold to stronghold wreaking havoc and waste. Rishanger noted that “the whole of that year trembled with the horrors of war … laying waste the fields … and spared neither churches nor cemeteries” as bodies were exhumed and robbed of their jewels to pay for the threatening wars.

Not to be outdone, the Royalist armies acted. Henry’s son, Prince Edward, and his followers looted the Treasury in London, causing the Londoners to rise in revolt against the King. Queen Eleanor was duly cursed and came under fire from the mob as they pelted her with garbage and worse, forcing her to flee to France.

Simon, desiring to settle the political upheaval diplomatically if possible, sailed across the English Channel and appealed to King Louis of France. Of course, the English earl wished the matter settled to his way of thinking, but this failed when Louis took the side of his fellow monarch.

Meanwhile, once Henry realized he was free of the Provisions, he wasted little time in bribing or otherwise enticing many of the rebellious nobles to return to supporting him. This left the hardcore anti-Royalists to foment rebellion. They were not as numerous as before, but they were committed … and angry. The earls of England sided evenly—six for the Royalists, six for the barons—when Henry gathered an army together at Woodstock in 1264.

The armies that would meet in battle during the Barons’ War, though not equally balanced in numbers of participants, were made up of similar troop types. The mail-armored cavalry, armed with lance and shield and riding war-horses, was considered the epitome of military evolution in the 11th and 12th centuries. The cavalry had ridden down the armies of the Lombards at Civitate (1053) and the Byzantine Empire at Durazzo (1081), and had proven its worth against the Saracens in the Levant at Arsuf (1191). For a time, the mounted knight was used as a dismounted foot soldier to bolster the ranks of unarmored foot, notably at Northallerton (1138). But as the 13th century dawned, the experiences from the Crusades as well as battles on the Continent made the mounted knights less inclined to dismount and fight on foot. By the time of the Battle of Lewes in 1264, the knights would fight as mounted warriors. Knights provided a powerful presence, with high-pommelled saddle and stirrups adding an incredible amount of kinetic energy to their charge.

By the 13th century, knights were quite heavily armored. They wore mail from head to toe, with many using a covered helm to protect their faces, although some knights continued to prefer the open-face helmets right up through the next century for their greater visual and aural acuity. Solid body armor had also begun to appear, as either boiled leather or plate, worn under the knight’s tunic and over his mail as chest and back protection. Armed with a lance and sword, as well as axes, maces, or clubs, knights were tough to face and increasingly difficult to wound or kill.

Cavalry charges did not assure success when launched at similarly armed and armored enemies. In fact, it became more difficult to coordinate an all-out mounted attack as the knightly armor became heavier and the helmets covered the entire head, cutting off sight and sound. Besides, if the enemy division also contained knights, they would launch their own attack as soon as they could, causing the two cavalry lines to crash into each other and rapidly dissolve into a series of individual contests. When the cavalry attack was directed at enemy foot units, the result was usually much different. Foot soldiers could and did at times manage to stand up to the mounted knights. These were exceptions, however. Most foot of this period had no armor and at best possessed a helmet and shield, so had little chance of resisting a charge in the open.

The use of archery is little noted in chronicles of the time. Perhaps this is because archers were looked upon as little more than a nuisance, or as minor auxiliaries in support of the noble knights. Nevertheless, archers and missile troops (who threw javelins) were usual components of most armies of the period. In addition to missile troops, large numbers of militia would often accompany armies. They provided bulk and could be used to anchor a section of the line, if properly supported. They were often assigned to a flank position, because if they broke they would not carry any other units away with them. Welsh troops were also used, primarily as auxiliaries in English armies, contributing numbers of spearmen and archers. Although of dubious quality morale-wise (often they were not that eager to serve their English “oppressors”), the Welsh did manage to make themselves more and more a contingent part of later English armies both in France and in Scotland.

As with most battles of this period, once the missile fire and knightly charges had been made, at some point one side or the other suffered a major loss of morale and that army broke. This could be immediate or take all day. The heaviest losses occurred at this time and during the pursuit. An army that lost a battle would often be reduced by as much as half or more of its former size. Tactical battle was always a gamble, but sometimes a necessary one to decide the existing political situation. Lewes was no exception.

Armies of the 13th century usually deployed into three divisions, or “battles” as they were called. Each division was usually commanded by a senior noble—by the King or commander-in-chief or one of his sons, brothers, or other trusted relatives. It was not unusual to find entire armies under the command of a single family, as evidenced by the de Hautevilles in Italy, Greece, and Sicily in the latter part of the 11th century. This was one way to ensure loyalty and firmness in battle, because nobles were sometimes not averse to changing sides if the situation warranted.

Each division was autonomous to a certain degree, and acted independently of the others. This allowed for some degree of tactical versatility insofar as launching attacks, defending against enemy charges, or making advantageous advances. Although command control could be a major problem with audio and visual signals hard to discern over the din of battle, commanders did sometimes manage to exercise an amazing ability to shift units and even entire divisions if necessary.

The opposing armies that would meet at Lewes were made up of the forces as well as the leadership types described above, and they would fight under the limitations as well as the advantages noted.

By April, Henry had managed to raise a large Royalist army in the English Midlands, while the baronial forces held London, Leicester, North- ampton, and Nottingham. Henry planned to capture the three baronial strongholds before marching on London. Northampton fell first, betrayed by a monk who let the Royalists in through a garden gate, costing Simon two of his sons and 15 barons captured. By April 11, Leicester had also been taken and sacked. Nottingham surrendered two days later.

Frustrated by the swift Royalist victories, Simon thought to move on Nottingham, but heard of the surrender and instead retreated to the safety of London. In fact, Henry’s bold moves had neutralized the baronial army. Simon’s attempt to capture the royal castle at Rochester was thwarted by the King’s move toward London, which Simon had to fall back to defend. This allowed Henry in turn to march on Rochester and relieve the beleaguered garrison.

In the late spring of 1264, after failing to secure the Cinque Ports, which lay on England’s southeast coast, Henry moved his army to Lewes, a town of about 2,000. The King had hoped to deny Simon any use of the English Channel or coastal areas for reinforcements, supplies, or an escape route if he were defeated. In marching west to Lewes, Henry also wanted to gather supporters, but Simon’s Welsh archers ambushed the column, forcing it to halt and rest.

The majority of the tired and hungry Royalists entered Lewes but moved through and made camp outside the town. More enterprising individuals decided to partake of the pleasures and food available within the town. Prince Edward, the future “Hammer of the Scots,” made his headquarters in the castle of Royalist ally—and another of Simon’s former friends—John de Warenne. The King and his brother, Richard of Cornwall (“The King of the Romans”), and their entourage made their lodgings at the Cluniac Priory of St. Pancras in the southern suburb of Lewes.

Simon realized that his chance at a military victory would erode as Henry’s army gained strength, so it took little in the way of persuasive argument to gather his own baronial army by the second week of May. Although outnumbered by the Royalists almost two to one (the King had 8,000 to 10,000 men, including 1,500 cavalry, while Simon had only 600 horse and perhaps 5,000 foot), he was confident of victory over the tired and demoralized Royalists.

Nonetheless, the barons dutifully sent several clerics to Henry to discuss terms. These were fairly straightforward: If Henry would once more accept the Oxford Provisions, the barons would pay the crown 50,000 pounds and again serve the King. Henry refused, sending word back to the barons that “they shall have no peace whatever, unless they put halters round their necks, and surrender themselves for us to hang.” The King had the numbers and he had, or so he thought, the strategic initiative. He was in no frame of mind to accept a compromise when he felt that total victory was within his grasp.

The baronial army marched toward Lewes with a contingent of London militia, which was of dubious fighting quality but at least held impressive numbers. De Montfort’s troops reportedly wore white crosses on their tunics, both front and back, most likely as a morale booster, emulating the Crusaders, while at the same time serving to differentiate them from their enemies. Simon’s confidence in his ability to inspire and command, along with his enthusiastic troops, allowed him to believe he could defeat the King, whom he considered an inept military commander. Indeed, the inability of the Royalists to effectively keep scouts out in the area allowed the baronial army to march to within two miles of Lewes on the morning of May 14, and an enemy sentry (reportedly there was only one) was captured while he slept. Reports also noted that many of the Royalists spent the night before the battle drinking and partaking of female companionship, no doubt contributing to their lack of attentiveness on the morning of the 14th.

The baronial army arrived before Lewes and began to assemble on two spurs north and west of the town. The battlefield had little terrain to impede cavalry, with only low hills and occasional clumps of trees and underbrush. Matthew of Westminster noted that the baronial army “placed their tents and baggage on a hill, the chariot of the Earl of Leicester [Simon], with his standard, being carefully placed under the brow.” A number of Royalist prisoners were with the baggage.

The Chronicle of Melrose includes the following passage: “Round about the carriage Simon had caused to be hung those flags that are called pennons, that by this means the king and his force might be deluded into the belief that Simon was in the chariot, in which, however, the true Simon was not.” Thus the Royalists would be inclined to think that the main strength of Simon’s army was gathered near the carriage, though this was not at all the case.

Thanks to this and other lack of proper reconnaissance on the part of the Royalists, the baronial army had time to assemble from their line of march, gather into four “battles” or divisions, and listen to a speech given by Simon. He urged his followers to pray for victory and so overcome their enemies. Unbelievably, the Royalists had still not been warned of the approach of the enemy army. It is difficult to understand the arrogance of the Royalist leaders, not bothering to have enough guards in outposts to keep watch for the baronial forces, known to be in the area.

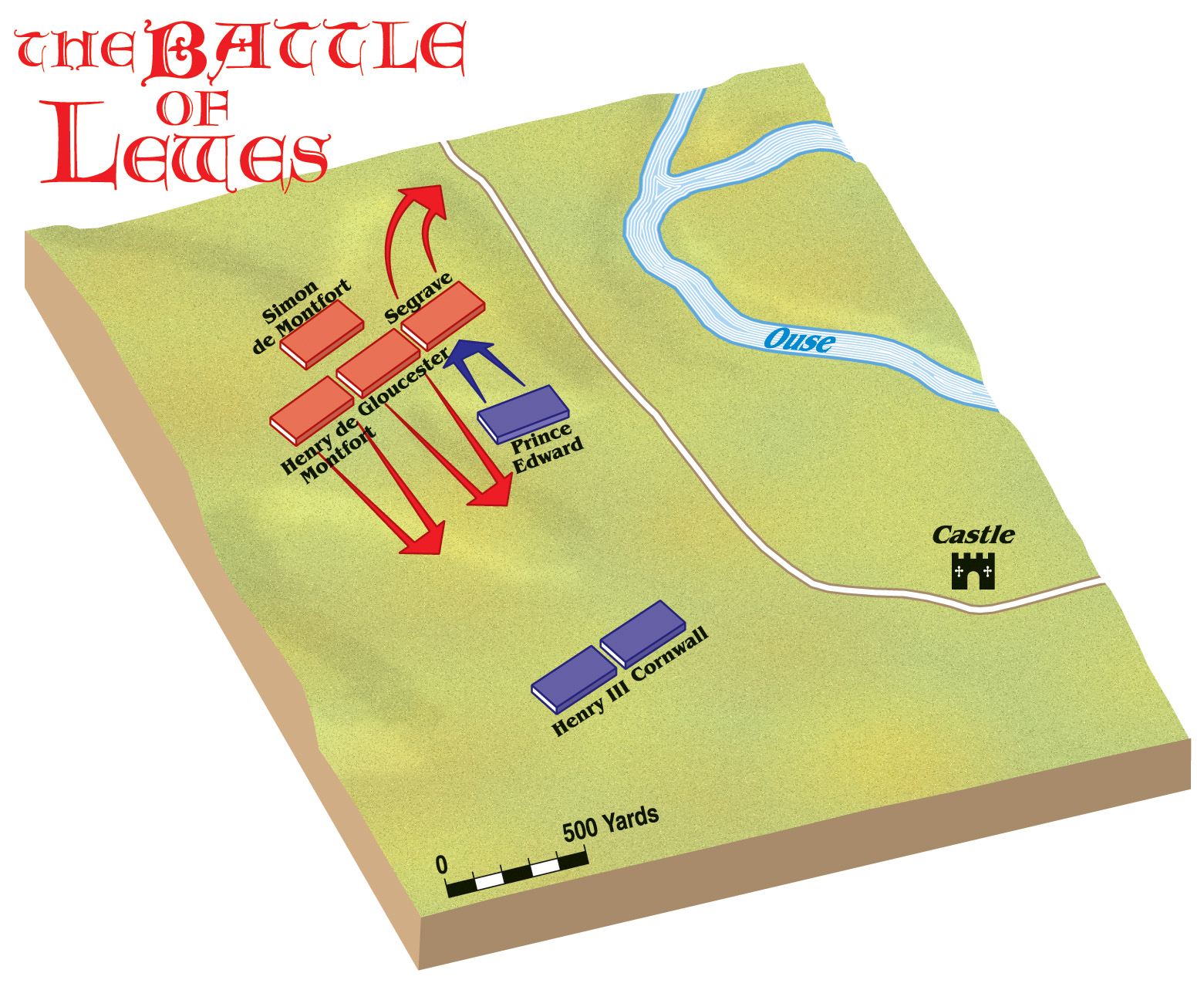

Simon’s plan was to use the large contingent of London foot under the command of Nicholas Segrave and Henry de Hastings to tempt the Royalists to attack with their cavalry while the baronial knights formed up on their flank and in reserve. Simon’s two sons, Guy and Henry de Montfort, commanded the right flank, while the Earl of Gloucester held the center. The Londoners were on the left. Simon kept his own knights in tactical reserve behind the other formations.

Then the baronial army moved downhill and apparently went undiscovered until it ran into a Royalist foraging party. These foragers were duly overwhelmed, but some managed to escape, spreading the news that the enemy was rapidly approaching. The baronial army was scarcely a mile away from the Royalists’ positions when the alarm was finally raised.

The Londoners had been ordered to set fire to the town of Lewes and then move behind the enemy and attack them in the rear as they tried to assemble in the ensuing confusion of battle. The Londoners believed that the rest of the baronial army would already have attacked and would be fighting with the Royalists, thus ensuring the militia an easy job. In reality, Simon was using the militia as an intended target for the Royalists knights and their impetuous young commander, Prince Edward.

Upon sighting the large block of London militia approaching the town, Prince Edward immediately ordered his knights called to arms. With a flurry of orders, the various contingents of the army quickly formed up and moved out of town, leaving a number of men behind in Lewes as a reserve.

Then Prince Edward, being closest to the advancing enemy army, led his own mounted command out of the castle and immediately charged toward the London militia … and Simon de Montfort’s banner in the wagons that had been stationed behind them. At the same time, King Henry led his division out of the Cluniac Priory, and with his brother Richard forming up on his left, the army made its way out into the fields before the baronial army. Archers apparently were present to harass the enemy ranks before hand-to-hand combat began. Charles Oman, writing in the early 20th century, believed that Simon de Montfort used Welsh archers both in his field armies and for reconnaissance missions. Other reports, notably John Ricall’s of about 1529, record that archers were also used by the Royalists at Lewes.

Matthew of Westminster described the developing battle: “The royal troops rapidly opened their close battalions, and boldly urged their horses against the enemy … and attacked them on the flank. And thus the two armies encountered each other, with fierce blows and horrid noises … the line of the barons was pierced and broken.” Although Matthew of Westminster notes that the Royalist army “marched forward on that day without any order, and with precipitation, and fought unskillfully, and showed no steady perseverance,” Prince Edward’s attack shattered the Londoners and sent them scattering through the fields, the mounted knights slaughtering the unarmored infantry as they attempted to outrun their pursuers.

This rapid destruction of a good part of his army might have unnerved another general, but Simon de Montfort had no illusions about the ability of militia to stand up to heavy cavalry. Foot could hold off knights if they were armed with long spears and knew from experience how to wield them. Foot had another incentive: Those who defeated knights had a very good chance of being set for life because they could loot enemy corpses, especially those of wealthy knights. Soldiers often fought for loot and plunder, and the Romance of Bauduin de Seboure noted that before battle, men would think, “There is going to be fighting here! Now I shall get rich!” But as J.F. Verbruggen put it, “Fear in the fighting man in time of war and on the battlefield is easy to see: if it is not quickly mastered men take to their heels, fleeing in whole units, or becoming panic-stricken.” Indeed, the London militia did not have long spears or experience in battle, nor did they have much of a chance as the English knights rode them down.

Prince Edward was soon elated because he not only saw half the baronial army fleeing before him, but he also captured the horse litter and Simon’s standard in the baronial baggage train. He had the occupants of the litter killed—but unfortunately these were the Royalist supporters who had been held prisoner by the barons—before turning his men loose to pursue and destroy the hated Londoners who had insulted his mother and father.

The Royalist knights kept up the pursuit for many miles as the Londoners fled from the field. But as Simon had hoped, the pursuit by the knights took a good portion of the Royalist army out of the general conflict.

Simon wasted no time ordering his own attacks. As the King and Richard of Cornwall were forming their own troops, Welsh archers rained arrows down upon the Royalists to their front, and the baronial heavy cavalry attacked them with both right and center divisions. Guy and Henry de Montfort’s command, along with the Earl of Gloucester’s, charged downhill, picking up momentum before smashing into Richard of Cornwall’s command.

The baronial attackers hit Richard of Cornwall’s division just as the rain of missiles and arrows destroyed any semblance of order. Although fighting stubbornly, the Royalist knights were forced back. But then the disordered division of Royalists broke and ran. Richard of Cornwall fled to a mill where, finding himself surrounded by enemy troops, he surrendered rather than face death.

Simon observed the unfolding situation before him and, keeping a wary eye on Prince Edward’s pursuing knights, ordered his own reserves into action against the King’s division. As King Henry unfurled his dragon banner, the baronial heavy cavalry rode into his unformed knights. When these battle lines clashed, the very air became filled with a loud clamor. As Jordan Fantosme noted at the clash of arms at Carlisle in 1173, “Great was the noise as the battle began; there was the ring of iron, and the clash of steel.” One report noted: “The champing horses felt the spur and the men, impatient to show their fighting skill, went winging down the hill to join the fray.”

According to the Chronicle of William Rishanger, the battle raged with a terrible ferocity as battle axes, broadswords, and maces caused much loss of life and limb. Little quarter was given or asked for as father fought against son and neighbor against townsman, “drunk with the blood of slaughter, the fallen struggling to raise themselves, the mutilation, the trampling under horses hooves, and those captured alive bound fast with chains.”

The Chronicle of Melrose notes that King Henry had his horse killed from under him. He managed to remount, but as he fought to defend the Royal standard, his second horse was killed. By this time the Royalists sensed the battle was lost and that the only thing to do was to get the King to safety. Several of the King’s retainers protected him as the Royalist army began to disintegrate.

Henry’s men fell back to town, then to the castle, and then to the priory, all the while continuing to fight in the hope that Prince Edward would return and once more sway the battle in the direction of the Royalists. The castle garrison and Henry’s archers fired flaming arrows into the town itself, trying to prevent the baronial army from overrunning them, setting many houses on fire and killing numerous townspeople.

Meanwhile, Prince Edward finally recalled his men from their pursuit of the hapless Londoners. As he returned to Lewes, he fully expected to see his father victorious. Instead he found the town in flames and the royal banner flying over the castle, the battlefield outside town covered with dead and dying men. Seeing the battlefield in the hands of the baronial army, many of Prince Edward’s men deserted him. Nevertheless, the prince and some of his followers fought their way to the priory and took sanctuary there. Others, including John de Warrenne with 200 cavalry, fought their way through the baronial forces to safety. This would have seemed the intelligent thing for the young prince to do as well, but instead he joined his father.

With the remnants of the Royal army bottled up in the castle and the priory, Simon sent a message to King Henry that if he did not immediately surrender the barons would execute Richard of Cornwall along with every other noble captured. This was a gamble on Simon’s part. If the King and his men refused to surrender, would de Montfort have dared to carry out such a deed? It did not come to that. With his plans in shambles and his field army destroyed, Henry capitulated. Many of his followers did not join him, preferring to take their chances in escape rather than trust in the barons’ good will. Many of the Royalists drowned in their attempt to swim across the Ouse River; an estimated 300 to 700 Royalist survivors fled to safety in France.

Casualties among knights during this era were usually very low, because a living knight could be exchanged for money. Foot soldiers —who had no ransom value—were not shown much in the way of leniency, however, and they would be cut down in large numbers as they fled before mounted knights.

Indeed, few knights lost their lives at Lewes. Nevertheless, the total Royalist losses were estimated at from 2,700 to an incredible 4,500 reported by Robert of Gloucester. Baronial losses must have been almost as high with the slaughtered Londoners providing most of the casualties.

Simon de Montfort’s victory won back in a single day the ground lost by the barons during the previous three years. Henry agreed to abide by the Provisions of Oxford, promised to reduce his expenses, and offered a full amnesty to Simon and Gloucester, not that he had much choice owing to the fact that he remained a virtual prisoner of the barons.

Nevertheless, the struggle continued. Only a year later, the baronial fortunes would be reversed. Simon and his cause would be destroyed by the Royalist forces at Evesham. King Henry, freed at Evesham, fought for another year against the remaining rebellious barons before peace was made. He died in 1272. Prince Edward succeeded his father as King and fought a successful war against Wales before becoming embroiled in Scottish politics. Although ultimately victorious against the rebellion of William Wallace, Edward could not continue the campaign against Robert Bruce, passing away in 1307 and leaving his kingdom in the hands of his son, Edward II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments