By Herb Kugel

In the 40 minutes between 7:50 and 8:30 am, on April 5, 1942, Royal Air force pilot Don McDonald experienced his air base being bombed in a Japanese surprise air raid that should never have been a surprise. He struggled to get his plane into the air as bombs rained down around him. He shot down a Japanese dive-bomber and crash-landed after his Hawker Hurricane was hit by fire from a Japanese Mitsubishi Zero. After all this, he drank iced tea in a plush hotel.

Training on the Hurricane

Although McDonald was flying with the Royal Air Force, he was a Canadian who first joined the Royal Canadian Air Force on August 14, 1940. He trained on a Fleet Finch and the North American Harvard and completed his flight training in April 1941. Rated a leading aircraftman, he was ordered to Halifax, Nova Scotia, for an overseas assignment. While traveling to Halifax, he received a telegram informing him that he had been promoted to pilot officer and that his pay would be raised from $2.25 per day to $6.25 per day, the equivalent increase of about $10,467 per year to $29,082 per year in current Canadian dollars.

McDonald was sent to Scotland and posted to 59 Operational Training Unit in June 1941. He soon found he had some unlearning to do when he started training on the Hawker Hurricane. In the Harvard, the pilot could handle both the throttle and undercarriage controls with his left hand, but in the Hurricane Mk I the throttle lever was on the left while the undercarriage lever was on the right. This meant that when taking off, if the pilot held the control column in his right hand, he had to use his left hand to open the throttle. Once in the air, he would have to take the control column in his left hand and use his right hand to operate the undercarriage lever.

McDonald recalled that in his first days of training he saw his plane’s wings dip as he changed hands and raised the undercarriage. He also recalled that many of his fellow trainees experienced the same problem.

In August 1941, McDonald was assigned to RAF 245 Squadron, stationed at Ballyhalbert, Northern Ireland. He soon learned to fly the Hurricane Mk IIB, a significant upgrade from the Hurricane Mk I. It carried a two-speed supercharger as well as a new and more powerful engine. A 1280 horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin XX engine replaced the Hurricane I’s 1030 horsepower Merlin II engine. While the Hurricane I carried eight .303-inch Browning machine guns, the Hurricane IIB was armed with 12 of these .303 Browning machine guns and also could carry two 250- or two 500-pound bombs.

McDonald quickly learned that flying the Hurricane IIB was not a trivial task. To get the feel of the supercharger, the student pilots were ordered to take their planes up to 15,000-16,000 feet but to turn on the supercharger at 13,000 feet. Climbing to 13,000 feet was no problem since the plane had a ceiling of some 34,000 feet, but when McDonald attempted to loop after turning on the Hurricane IIB’s supercharger his plane would not pull back at the top of the loop but climbed straight up no matter what he did. His engine quit, and the plane fell into a spin. McDonald managed to restart the engine and recover control.

Patrolling the Mediterranean

In September 1941, the squadron was transferred to Chilbolton, Hampshire, in southern England, from where it engaged in offensive sweeps across the English Channel. The squadron also provided air cover for convoys, sometimes flying in formation through heavy clouds. In September, the squadron was re-equipped with the Hurricane IIC, which was armed with four 20mm Hispano cannons as well as having bomb-carrying capabilities.

McDonald’s comments about the plane’s cannons were not enthusiastic. “You had the impression when practice firing them, that the Hurricane stopped from the cannons’ recoil,” he said. “If one side jammed—as they did— you would yaw violently off target.”

On October 24, 1941, McDonald was posted to 30 Squadron, flying the Hurricane IIB, in the Middle East. He traveled with others through Freetown, Sierra Leone, and then to the Gold Coast (now Ghana); there an American pilot flying a Douglas DC-3 transported them to Khartoum in the Sudan. McDonald could make out the words “American Airlines” lightly painted over on the DC-3’s fuselage.

At Khartoum, a BOAC flying boat took them to Cairo, and from there they traveled by land to an advance base near Sidi Barráni, an Egyptian town 59 miles east of the Libyan border. On the trip, Don met Flight Lieutenant R.T.P. “Bob” Davidson, who had rejoined the squadron after serving with it in Greece and Crete. McDonald felt fortunate that he was assigned to Davidson’s B Flight.

McDonald’s group reached Sidi Barráni during a time of heavy fighting. German and Italian units attacking from Libya were engaged in seesaw battles with British, Australian, and other British Empire forces for control of North Africa.

The RAF had created a unique antiaircraft system to protect its airfields. A string of rockets spaced about 40 feet apart were wired to a manned and heavily sandbagged sentry post. When enemy planes strafed the field, the sentry fired the rockets, which went up with chains trailing behind them. A parachute then opened and kept the chains in the air for a few minutes, hopefully long enough to entangle any enemy plane that flew through.

Because Sidi Barráni was near the Mediterranean, McDonald regularly flew on convoy patrol. This was dangerous not only because of enemy planes, but also because of antiaircraft fire from the Allied ships the squadron was trying to protect. The naval gun crews were shooting first and questioning later. As an RAF squadron approached an Allied convoy, the squadron leader fired a Very pistol, a pistol that discharged colored signal flares, and sent up the identification colors of the day. Even with this, the RAF pilots were warned never to fly directly over a convoy.

The Monocle Squadron</3>

In early February 1942, Bob Davidson informed the squadron members that they were being transferred to Singapore to fight the Japanese. “Woolworth-type aircraft, fixed undercarriages, fixed pitch propellers. It’ll be a piece of cake,” he commented on the enemy he expected to face in the air. Davidson was wrong. The Japanese Zero fighters were the first carrier-based fighters to outperform similar land-based planes. They carried drop tanks and retractable landing gear and were definitely not Woolworth-type aircraft.

McDonald’s 30 Squadron flew to Heliopolis, a town some six miles northeast of Cairo. After checking into a hotel, the fliers went downtown to the local bars and nightclubs, where Davidson caused a stir. He had been given permission to grow a beard, and evidently some of the bars’ and nightclubs’ more hidebound British clients were unhappy at seeing an RAF officer wearing a beard. In several places, these stuffier patrons put on their monocles and stared disapprovingly at the pilots.

However, the pilots held their own. They purchased monocles. When anyone put on a monocle and sneered at Davidson, the pilots put on their monocles and sneered back. From then on, 30 Squadron was known as the Monocle Squadron.

The squadron was moved from Heliopolis to Ismâ’ilîya, a town on the Suez Canal. Equipment and personnel then sailed south to Port Sudan on the Red Sea and transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable. The pilots of the Indomitable’s Fleet Air Arm Squadron looked on enviously. They flew the Hurricane I, as they were told that the Hurricane IIB was too fast to land on a carrier deck.

Deployed to Ceylon

The squadron was to be sent to Singapore, which was under Japanese attack, but the city fell before its arrival. With Singapore captured, Ceylon was in critical danger. Sir Winston Churchill said: “The most dangerous moment of the War, and the one which caused me the greatest alarm, was when the Japanese Fleet was heading for Ceylon and the naval base there. The capture of Ceylon, the consequent control of the Indian Ocean, and the possibility at the same time of a German conquest of Egypt would have closed the ring and the future would have been black.”

Therefore, 30 Squadron was redirected to Ceylon. When the Indomitable reached the island, the pilots were told they would take off from the carrier. This was interesting news since none of the pilots had ever flown from a carrier. The plan was for the pilots to clamp down their brakes and then rev up their engines. The brakes were then released as full power was applied. It was hoped that the Hurricane would then shoot off the carrier deck and lurch into the air.

On March 6, the first planes were launched. Davidson went first; McDonald, his number two, was directly behind him. McDonald’s stomach dropped as he saw Davidson’s Hurricane go over the bow of the ship and then drop from sight. He breathed easier when he saw it climb into view.

All 24 planes of 30 Squadron reached Ceylon safely and landed at Ratmalana Airport, seven miles south of Colombo, the capital. The airport, almost on the shores of the Indian Ocean, had its runway doubled in length to accept both 30 Squadron and 11 Squadron, which flew the twin-engine, three-seat Bristol Blenheim light bomber. Several other units arrived or were placed on alert as the British struggled to shuffle together what was at best a makeshift defense. A newly constituted Hurricane 258 Squadron was readied. RAF Hurricane 261 Squadron was alerted, as were three Fleet Air Arm squadrons, Fairey Swordfish 788 Squadron and Fairey Fulmar 803 and 806 Squadrons.

However, nothing the British could hurriedly patch together matched the power of the attackers who moved against them: Japan’s elite striking force, the First Air Fleet, which had devastated Pearl Harbor. It consisted of five modern aircraft carriers, four battleships, and 14 other vessels. The Japanese were not to invade Ceylon but to destroy the Royal Navy’s Eastern Fleet, which the Japanese thought was still based there.

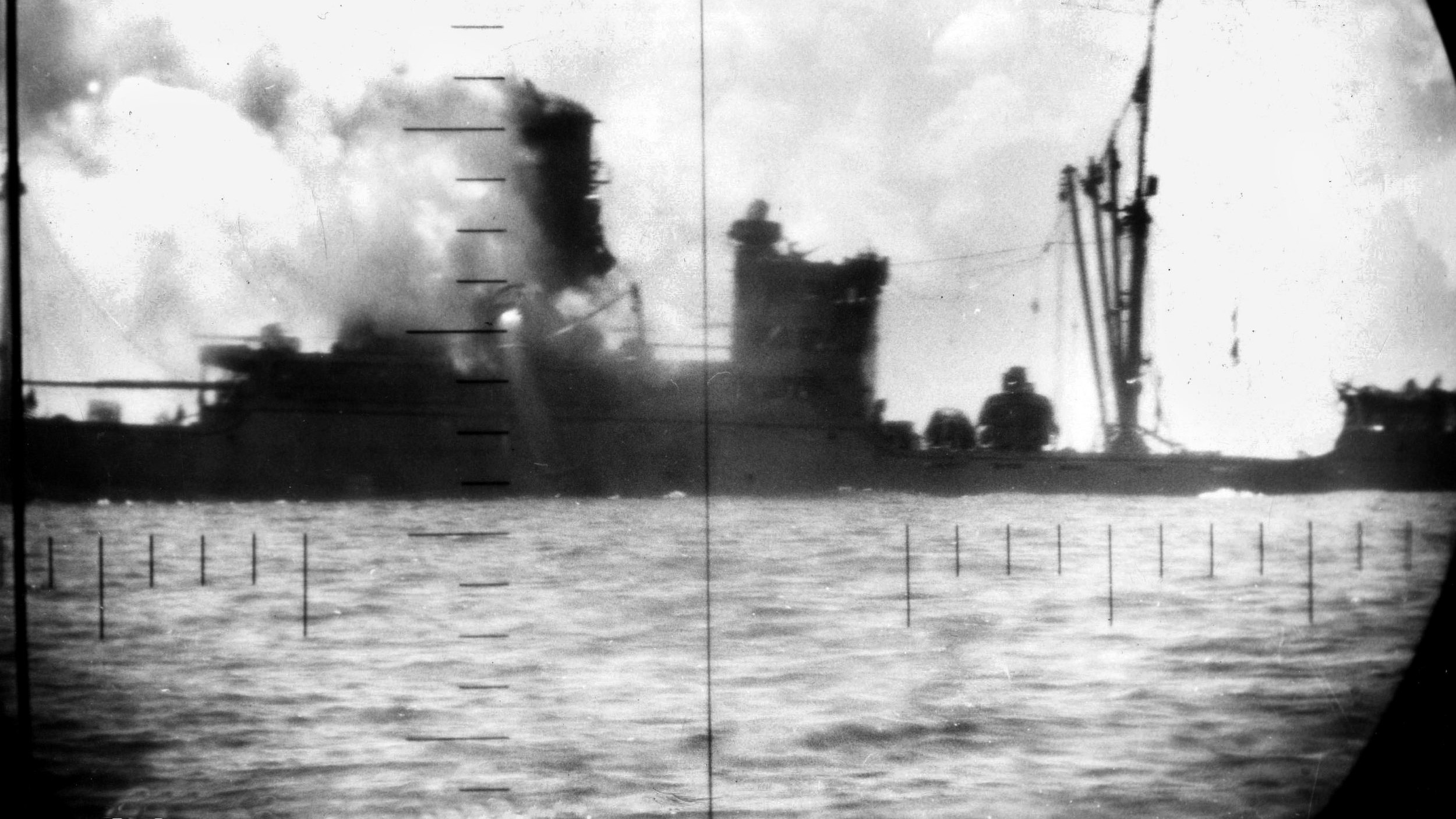

Attack on 30 Squadron

By April 4, 1942, the First Air Fleet was only 360 miles southeast of Ceylon when it was spotted by pilot Leonard Birchall of 413 Squadron. Birchall, who was the first of his squadron to arrive from the Shetland Islands, was piloting a Canadian Consolidated Canso PBY flying boat. He radioed a warning to Ceylon before his plane was shot down. The Japanese knew they had been discovered but continued with their plans, readying an attack for the following morning, Easter Sunday, April 5, 1942.

The Japanese planes took to the air before dawn. Their attack was led by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid included 36 Zero fighters escorting 36 Aichi D3A1 Val dive-bombers and 53 Nakajima B5N Kate attack bombers. An additional 180 Japanese planes were on alert should they be needed. The Japanese achieved surprise despite Birchall’s warning. While 30 Squadron was on the alert, British radar was not.

McDonald later reported, “We stood at readiness from about 2 am … About 6 am half of us went for breakfast, and we had just arrived back … when we heard engines roaring overhead and looked up and saw formations of aircraft coming over the tops of large cumulous clouds. We later found that the radar shut down regularly on Sunday mornings for maintenance. Apparently no one alerted them….” There may have been more incompetence than that. It was possible that what little radar the British had at Colombo was unmanned not because of maintenance but because of carelessness during a shift change. Also, the RAF Colombo Fighter Operations Command was apparently unaware of the range of the Zero or that it could carry drop tanks; they expected the attack the next day.

To make matters worse, the standing order regarding the Ratmalana control tower was that the controller, on hearing unidentified aircraft, was to step onto the balcony and fire a red warning flare from his Very pistol. However, in his excitement, the controller discharged his pistol inside the tower. The flare bounced around, and no alert was given. Despite the fact the Japanese had been flying over Ceylon for about half an hour, 30 Squadron was caught on the ground.

Fuchida’s main force roared over the airport on its way to the docks and the hoped-for destruction of the British Eastern Fleet, but some of his planes diverted to attack the airport. The Hurricanes of 30 Squadron were parked on the north side of the field. McDonald and other pilots jumped into a truck that sped them to their planes. When the truck arrived, McDonald saw Bob Davidson and another pilot taxiing across the runway as bombs started to fall around them.

One Hurricane was destroyed taxiing to the runway. Those planes that made it to the runway lined up in no particular order and took off in sections of two without the opportunity to operate as a squadron. The first heavy casualties of the Japanese attack included the native construction laborers working on the runway. They were used to planes taking off and the sound of guns. Nobody thought to warn them of a probable Japanese attack. They were caught in the open when the bombing began.

Shot Down over Colombo

McDonald took off flying number two to Flight Sergeant Tom Paxton. He managed to gain height, but when he came out of a cloud he saw six to eight Val dive-bombers flying toward Ratmalana Airport. McDonald attacked the end bomber. The Hurricanes were carrying straight ball-type ammunition because a few weeks earlier the incendiary bullets in one of the Hurricanes had started to explode. The bullets had been left uncovered in the sun, and the explosions had been caused by Ceylon’s intense heat.

Because of his ball-type ammunition, McDonald could not initially see if he was hitting the Val, but he suddenly noticed liquid pouring from under the dive-bomber’s wing. At the same time two Zeros jumped him. To McDonald’s surprise, the Japanese pilots appeared to know exactly what they were doing. He remembered thinking, “These guys didn’t come from Woolworth’s.” He knew his one chance of escape was to outdive the Zeros, but the Japanese fighters remained on top of him.

Bullets smashed into McDonald’s engine; oil and glycol covered his windscreen. McDonald opened his canopy, and the slipstream yanked his goggles to the back of his head. He pulled them off and threw them away, realizing that he was flying over Colombo and away from the airport. He knew that without glycol his engine would quickly overheat and lock up.

McDonald realized he had to crash-land soon, so he determined to try for Galle Face Green, a long, wide stretch of grass that was bordered on the west by the Indian Ocean. He had to fly over the harbor to get to the green, and he heard the explosions of friendly antiaircraft fire all around him. Some of the shipboard gunners were taking no chances; they shot at anything above them. McDonald throttled back on his landing approach. His instruments were completely covered with oil and glycol. He had no idea how fast he was going and later stated that his Hurricane “must have been going at a pretty fair clip because when it touched down, the air cooler below the cockpit was torn off.”

“Cold Tea”

When the Hurricane finally stopped, McDonald was surprised to see the air cooler bounce along and land beside the port wing. He climbed out of his damaged plane and was greeted by two senior British Army officers. The three men started walking toward the nearby Colombo Club but were stopped by a small car driven by an RAF officer. McDonald got in and was driven to the Galle Face Hotel at the south end of the green. The lobby was filled with excited people, many still in their nightclothes. A man came up to him and said, “You need a drink.”

McDonald thought this was an excellent idea. The man quickly returned from the kitchen with a glass filled with an amber liquid that looked like Scotch whiskey. McDonald took a long gulp. “What the hell is this?” he demanded. “Cold tea,” the man replied. It was just 8:30 in the morning. The hotel bar was closed. The Japanese attack on Ceylon failed to destroy the British Eastern Fleet. Unknown to the Japanese, the British ships had been alerted and had moved to sea. The Japanese sank only an armed British merchant cruiser and an old destroyer.

There are conflicting figures on air losses. Including the Fleet Air Arm, the British may have lost between 25 and 37 planes. Five 30 Squadron pilots died in the action, and this is not disputed. One was Tom Paxton, who was badly burned and died on April 7. Paxton had shot down one of the two Zeros that attacked McDonald. He also confirmed that the Val McDonald hit crashed into the sea.

While figures on Japanese losses are also contradictory, 30 Squadron claimed 14 Japanese planes destroyed, six probably destroyed, and five damaged. This was part of a claim that a total of 19 Japanese planes were destroyed, seven were probably destroyed, and nine were damaged in air combat. Some historians dispute these figures, but if it is reasonable to assume the Japanese lost about 20 percent of their force, this would be a loss of 25 planes.

The allegedly invincible First Air Fleet received a bloody nose from the pitifully few planes the British scraped together. During the subsequent naval Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, those experienced pilots lost in the skies above Ceylon were sorely missed by the Japanese.

McDonald survived the war, and in 1946 he served with Operation Muskox, a Canadian arctic military exercise. He left the Royal Canadian Air Force after this and spent many years working in the private sector.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments