By Don Hollway

In November 1455 a most extraordinary ecclesiastical court convened in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris at the behest of the French Inquisition. No less than Pope Callixtus III had appointed three judges, including the archbishop of Reims, the highest officer of the church in France, to preside. Clergymen from across Europe attended. As many as 115 witnesses were called, from peasants and soldiers to priests and noblemen. At issue was whether French King Charles VII had committed heresy and used witchcraft in achieving victory over the English in the Hundred Years War. The crux of the matter turned on events a generation past, thought by some miraculous and by others diabolical.

The defendant herself was not present, having those long years past been accused, tried, and brutally punished. Her testimony and that of witnesses, though, had been entered into the court record and survive today. In that first trial, in 1431, she had referred to herself, in the medieval French of her day, as Joan the Maid. She was already famous as Joan of Arc.

In his youth Jean d’Orleans, Lord of Valbonais, Count of Dunois and Longueville, had known the Maid well. “I think that Joan was sent by God, and that her behavior in war was a fact divine rather than human,” he testified 21/2decades later. “Many reasons make me think so.”

In February 1429 Dunois, then just 26, was known only as the Bastard of Orleans, but his rank in French service was that of a lieutenant general. “Bastard” was a term of respect, and it meant that his father, Louis I, Duke of Orleans, had acknowledged him as his son. Dunois and his 200 knights had joined Charles de Bourbon, Count of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis, to intercept an English supply caravan at Rouvray, north of Orleans. The convoy, which consisted of 300 wagons and carts “laden with victuals, and with much war gear as cannons, bows, bundles, arrows and other things,” according to the Journal of the Siege of Orleans compiled at the time, was protected by 1,500 English knights, foot soldiers, and archers under Sir John Fastolf. Seeing the French readying an attack, they circled their wagons in a hedge of sharpened stakes “and put themselves in good order of battle, waiting there to live or die; for to escape they had scarcely hope, considering their small number against the multitude of French.”

The French numbered 4,000 knights and men-at-arms, not to mention a Scottish force led by Sir John Stewart of Darnley, the Constable of Scotland. The Scots and French had formed the Auld Alliance in 1294 to keep the English in check, but in this case could not agree on tactics. The terrain at Rouvray was flat, perfect for cavalry, but despite his numerical advantage Clermont, recalling the hedges of stakes that had foiled French knights at Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt, and the longbows that had slaughtered them, insisted they wait for reinforcements. His own archers were unable to drive the English out of their wagon park, and his cannoneers’ nonexplosive stone balls caused few casualties and small annoyance, except that smashed supply casks scattered salt-cured herring everywhere. This was in preparation for Lent, when both sides disdained meat. Darnley, on the other hand, was too eager to attack. “He disobeyed the order which had been given to all that none should dismount, for he began to assault without waiting for the others and, at his example, to help him, dismounted likewise the Bastard of Orleans … and many other knights and esquires with about 400 combatants,” according to the Journal.

The Scots had given up the advantage of numbers, and Dunois’ knights the advantage of fighting from horseback, but Clermont still hesitated to risk his cavalry against English archers. “When the English saw that the great battle [the main French formation], which were quite far off, came on timidly, and joined not with the Constable, they charged out swiftly from their park and struck among the French who were on foot, and put them to rout and flight,” stated the Journal.

In the Battle of the Herrings fought on February 12, 1429, Stewart was slain, as were most of the Scots and those French who had joined the attack. Dunois, with his surcoat and shield of blue with gold fleurs-de-lis (for the dukes of Orleans were of royal blood), made a prime target in the swarm of poorly equipped men-at-arms. He was struck in the foot by an arrow: “Two of his archers dragged him with great difficulty out of the press, put him on a horse and thus saved him,” stated the Journal. The French knight Etienne de Vignolles “rallied to the number of sixty or eighty combatants and struck at the English who were thus scattered, so that they killed many,” according to the Journal. “And certainly had all the other French turned about as they did, the honor and profit of the day would have been with them.”

But Clermont and the main French army “never even pretended to succor their companions, as much because they had dismounted [to fight] on foot against the general agreement, as because they saw them almost all killed before their eyes.” They left the field to the English, covered with dead men and dead fish, to be remembered ever after as the Battle of the Herrings. A few days later Clermont abandoned Orleans as well, leaving Dunois and his few remaining defenders on their own.

Eighty years into the Hundred Years War, France was at its low point. The English and rebel Burgundians ruled half the country. In October 1428 Thomas of Montacute, Earl of Salisbury, and John Lord Talbot, who was called both the “English Achilles” and the “Scourge of France” by the French, had surrounded Orleans and cut it off from the south. If the city capitulated, the river Loire would bear the English into the heart of France, and the Valois Dauphin Charles VII would fall. Although Charles was the heir to Valois France, the Treaty of Troyes of 1420 signed by the late King Charles VI set forth that the infant English King Henry VI was the King of France; however, the treaty was not recognized beyond the areas controlled by the English and Burgundians.

“I was at Orleans, then besieged by the English when the report spread that a young girl, commonly called the Maid, had just passed through Gien [upriver from Orleans], going to the noble Dauphin, with the avowed intention of raising the siege of Orleans and conducting the Dauphin to Reims for his anointing,” said Dunois.

In the spring of 1429 news of this 17-year-old girl from Lorraine in the eastern Meuse valley was all over France, or at least the half of it that was still French. It was said she talked to angels. They had told her of the Battle of the Herrings, even though her little village of Domremy was 200 miles away. With this revelation she had convinced the commander of neighboring Vaucouleurs to outfit her with men’s clothing, a horse, and an armed escort. They had ridden 300 miles through enemy territory to the dauphin’s castle at Chinon.

Dunois had sent his own riders to the palace to learn the truth of this. They said this Maid had recognized Charles, though she had never met him and even though he, advised not to trust her, had disguised himself as a courtier. She spoke to him in private of secrets only he and God could know and had indeed promised to raise the siege of Orleans and see him crowned king. It had been prophesied that France would be saved by a virgin from Lorraine, and so Charles ordered a suit of armor made for her, and a 12-foot white banner trimmed in silk with painted saints and fleurs-de-lis, and sent la Pucelle, the Maid, to join his army.

At Blois, downriver from Orleans, Joan found an army of 2,500 soldiers and a supply train with wheat, cattle, sheep, and pigs. The dauphin had called upon any captain who could supply troops, regardless of quality: dregs scraped from garrisons and militias of cities still loyal, mercenaries, and ecorcheurs (flayers). The ecorcheurs were unemployed soldiers who dabbled in banditry. They stole, drank, gambled, and caroused with prostitutes and camp followers.

All of this Joan abhorred and forbade, and, in what seemed to be yet another miracle, she was largely obeyed. “She would not permit any of those in her company to steal anything; nor would she ever eat of food which she knew to be stolen,” said squire Simon Baucroix. “She would never permit women of ill-fame to follow the army. None of them dared to come into her presence; but, if any of them appeared, she made them depart unless the soldiers were willing to marry them.”

“She was very vexed if she heard any of the soldiers swear,” added Jean II, the Duke d’Alençon. “She reproved me much and strongly when I sometimes swore; and when I saw her I refrained from swearing.” In 1429 d’Alençon was just 20, but in 1455 he still recalled the effect this petite Maid, with her dark eyes and complexion and short black hair, had on him and the other men.

“Even though she was a young girl, beautiful and shapely, and there were many times, when helping her to put on her armor or otherwise, I saw her breasts [under her clothing]; and sometimes her legs completely bare when dressing her wounds, and I went near to her many times, and I was strong, young and in my prime, never did I feel carnal desire towards her from any sight or contact I had with the Maiden; neither did any of her soldiers or squires, based on what I heard them say many times,” said d’Alençon.

Joan wished to cross the Loire and advance directly on the strongest English positions north and west of Orleans, but the caravan kept to the south bank and on April 29 arrived at Checy, five miles east of the city. Dunois crossed the river to meet them. The Burgundy Gate in Orleans’ eastern wall was still open, and small parties of men entering or leaving were of little concern to the English. Two and a half decades later Dunois well remembered his first encounter with Joan. She wore white armor; in other words, armor that was plain and unadorned, and had the look of a knight, but none of the manners. “Are you the Bastard of Orleans?” she asked.

“Yes, and I am very glad of your coming!” he replied.

“Is it you who said I was to come on this side [of the Loire], and that I should not go direct to the side where Talbot and the English are?”

“Yes, and those more wise than I are of the same opinion, for our greater success and safety.”

“In God’s Name, the counsel of My Lord is safer and wiser than yours,” she said. “You thought to deceive me, and it is yourselves who are deceived.”

“I had begged her to cross the river and to enter the town, where many were longing for her,” said Dunois. “She had made a difficulty about it.” He finally convinced her that their first duty was getting the provisions into the city (actually the army turned back for Blois), but that presented another problem. “It was necessary to load the convoy on boats, which were procured with difficulty. But to reach Orleans it was necessary to sail against the stream, and the wind was altogether contrary.”

“This succor does not come from me, but from God Himself, Who, at the prayers of Saint Louis and Saint Charlemagne, has had compassion on the town of Orleans,” said Joan.

“At that moment, the wind, being contrary, and thereby preventing the boats going up the river … turned all at once and became favorable,” said Dunois. “They stretched the sails; and I ordered the boats to the town.”

That evening Joan, with her white horse and banner, in her gleaming new armor, rode through Orleans by torchlight. Baucroix testified to her reaction: “In God’s Name!” she said. “Our people are hard pressed…. My Lord has sent me to succor this good town of Orleans. Hope in God. If you have good hope and faith in him, you shall be delivered from your enemies.”

Dunois called a council of war the next day to explain the military situation to Joan. Orleans, with its south wall to the Loire, formed a salient in the English lines. Its only link to friendly territory was a quarter-mile stone arch bridge, with a fortified, twin-towered gatehouse, les Tourelles, connected by drawbridge to the south bank. At the onset of the siege the English had made that their primary objective, and stormed its outlying boulevard, bulwark, in the ruins of the Convent of the Augustins. The French put up a stalwart defense, killing 240 English and losing 200 of their own. With Salisbury threatening to undermine their position, they abandoned the Augustins and pulled back into the Tourelles.

Like the bridge, the gatehouse had been built in the 12th century, before the advent of gunpowder. Although it had been recently strengthened, English cannons rendered it indefensible. So the French had withdrawn into the city altogether, cutting the bridge behind them. The English had fortified the Tourelles, as well as the ruins of the Augustins and Saint-Jean-de-Blanc, just to the east.

The good news was, three days after taking the Tourelles, Salisbury had been standing in an upper window of the Tourelles and was struck by a French cannonball. He had died soon after, leaving command to the less aggressive William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. Without enough men to take the city, Suffolk had settled for building strongpoints in a circle around it; without enough men to storm them, Dunois and the Dauphin had settled for a siege.

But Joan would not settle. She wanted a fight, and for that they would need men. Dunois’ lieutenant de Vignolles, the hero of the Herrings, called La Hire (Hedgehog) for his bristly temper, took her side; other knights were dubious. Dunois insisted Joan at least wait until he rode to Blois to fetch back the army. “On her return I saw she was quite vexed that, as she told me, the captains had decided not to attack the English on that day,” recalled her page, Louis de Coutes, who was 14 years old at the time.

That evening Joan went out to the farthest point of the bridge over the Loire, where the French had fortified their side of the break in the span. Calling out to the English opposite, she told them “if they would yield themselves at God’s command their lives were safe,” according to the Journal.

Sir William Glasdale commanded the Tourelles. As de Coutes recalled, he shouted back, “Do you wish us to surrender to a woman?” Glasdale “answered basely, insulting her and calling her ‘cow-girl,’ shouting very loudly that they would have her burned if they could lay hands on her.”

While Dunois was gone, Joan rode about the city, scouting the English positions. “I went there shortly after and saw the works which had been raised by the English before the town,” said d’Alençon. “I was able to study the strength of these works: and I think that, to have made themselves masters of these—above all, the Fort of the Tourelles at the end of the bridge, and the Fort of the Augustins—the French needed a real miracle. If I had been in either one or the other, with only a few men, I should have ventured to defy the power of a whole army for six or seven days: and they would not have been able, I think, to have mastered it.”

On the fourth day came news of Dunois’ return. Joan, La Hire, and their soldiers rode out to meet him, right past the Boulevard Saint-Loup, east of Orleans, where the English had fortified another former convent. The garrison there, looking out on Dunois’ huge new French force, gave it no excuse to attack.

This was because Fastolf supposedly was en route within a day’s ride with English reinforcements. In reality, he would not leave Paris for another month. Joan was thrilled: “Bastard, Bastard, in the Name of God I command you that, so soon as you know of the coming of the said Fastolf, you will let me know; for, if he passes without my knowing, I promise you I will have your head.”

Dunois, by now familiar with Joan’s sense of tact, assured her he would. She lay down to rest but not long afterward leaped from her bed, rousing those with her and scolding de Coutes, “Ha! Bloody boy, you did not tell me the blood of France was being shed!”

How she knew it is another of Joan’s mysteries. A force of 1,500 French had taken it upon themselves to assault the Boulevard Saint-Loup. “These captains and other warriors were all amazed at her words; most of them took up arms, and went with her to assault the bastille of Saint-Loup, which was very strong,” wrote French chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet.

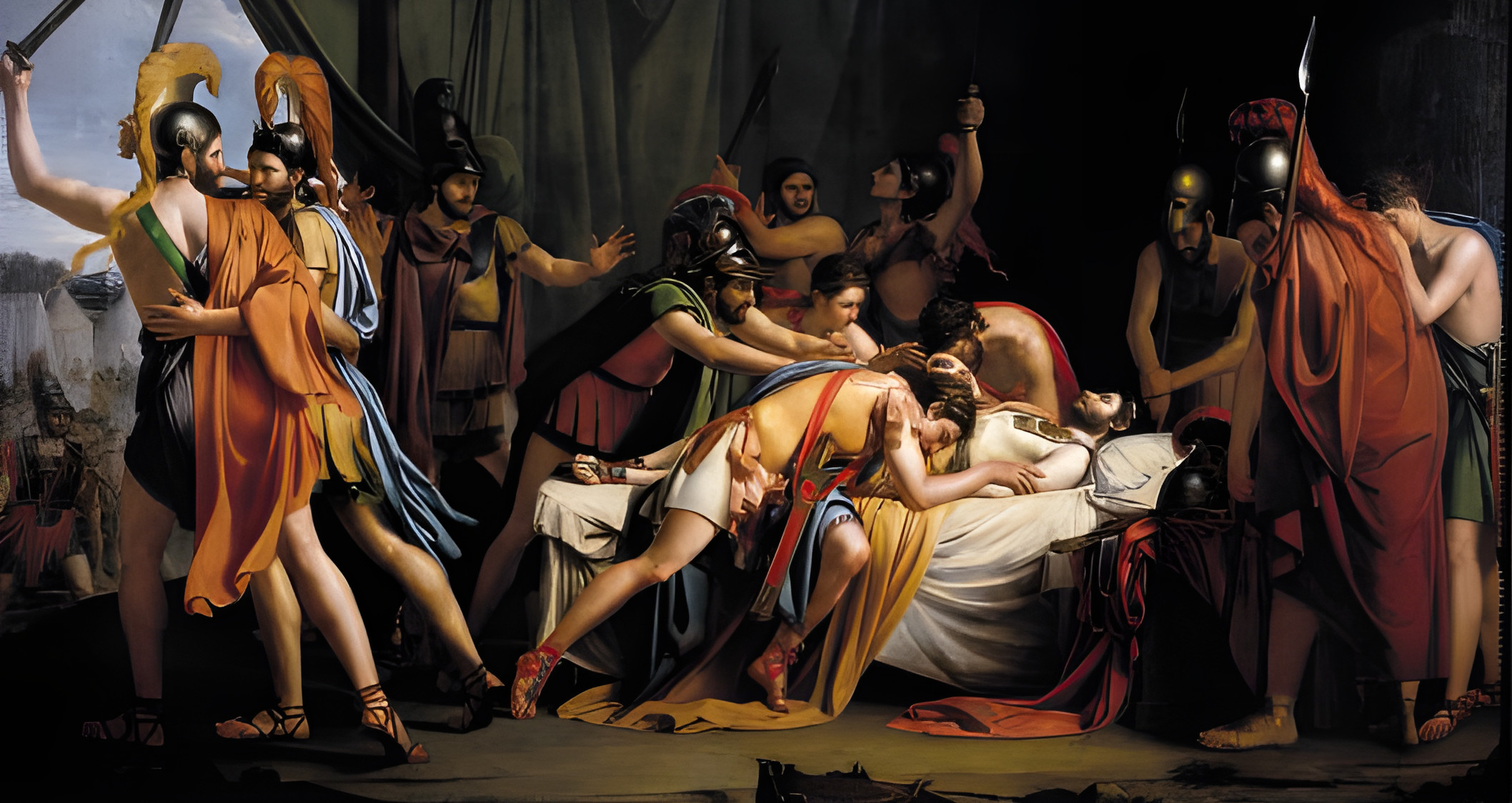

Suddenly the besiegers were besieged. While archers, crossbowmen, and handgunners fired from behind pavises to keep the defenders’ heads down, the attackers laid their scaling ladders against the convent walls and climbed, relying on shields and kettle helmets to ward off rocks, arrows, and quarrels raining from above.

Once over the top, the fighting was man-to-man, with sword and axe, mace, and war hammer. Accounts make no claim that Joan took direct part in the fighting, for she hated to shed blood herself, but this was her first battle, and with her white banner and silvery armor she was the shining inspiration for victory. About 140 English were killed and 40 captured. “The fortification was entirely demolished and delivered to fire and flame,” wrote De Monstrelet.

“From that hour, the English who, up to that time, could, I affirm, with two hundred of their men, have put to rout 800 or 1,000 of ours, were unable, with all their power, to resist 400 or 500 French; they had to be driven into their forts, where they took refuge, and from whence they dared not come forth,” wrote Dunois.

No more needed to be done. The road east was clear, Orleans could be supplied indefinitely, and its garrison was strong. That was not enough for Joan. The next day she led the army out of the Burgundy Gate and across the river on an improvised pontoon bridge toward the Port Saint-Jean-de-Blanc. Like Saint-Loup on the north bank, this was too far east and too exposed for its own defense. “The English who were in it no sooner saw the French coming than they went away and withdrew into another stronger and bigger bastion called the Bastion of the Augustins,” recalled Jean d’Aulon, a knight appointed by Charles to be Joan’s squire and bodyguard.

Supported by fire from the Tourelles just behind it, this was an entirely different proposition. French willpower faltered, and the enemy took advantage. “The English sallied out of the Tourelles in great strength, shouting loudly, and made a charge against them which was very strong and harsh,” stated the Journal.

Dunois was wrong. A few English could still overawe a horde of French—unless Joan was with them. “At once the Maid and La Hire, who were always before them to guard them, couched their lances and were the first to strike among the enemies,” said d’Aulon.

“In God’s name, let us go on bravely!” cried Joan.

“Thereupon all the others followed them, and began to strike at the enemy in such fashion that by force they drove them to retire and enter again into the bastion of the Augustins,” said d’Aulon. The French poured in after them. “There were killed or taken the greater part of the enemy; and those who were able to save themselves retreated into the Fort of the Tourelles, at the foot of the bridge.”

Joan wished to attack the Tourelles immediately, but Dunois called a halt for the night. It had been a great victory, the greatest since the beginning of the siege. He and his captains held a council of war to which she was not invited. Her confessor, Father Jean Pasquerel, remembered that afterward a knight informed her they were resolved not to attack in the morning: “The town is full of supplies; we could keep it well while we await fresh succor, which the King could send us; it does not seem expedient to the Council that the army should go forth tomorrow,” said the knight.

“You have been to your Counsel, and I have been to mine, and believe me the Counsel of God will be accomplished and will succeed; yours on the contrary will perish,” replied Joan. She then told Pasquerel, “Rise tomorrow morning even earlier than you did today; do your best; keep always near me; for tomorrow I shall have yet more to do, and much greater things; tomorrow blood shall flow from my body, above the breast.”

“The next day, in the morning, the Maid sent to fetch all the lords and captains before the captured fort [the Augustins], to consult as to what more should be done. French knights could hardly show timidity in front of a teenage girl,” testified d’Aulon. They agreed to attack after all.

Before they could reach the Tourelles gatehouse, though, the French in the Augustins would have to overcome no less than seven successive obstacles. Its outer wooden palisade was quickly smashed by French bombards, only to reveal behind it a ditch 10 feet wide and 20 feet deep. Crossing points had to be filled with fascines of sticks and branches while, from the far side, the English atop an earthen bulwark kept up a barrage of arrows, bolts, and cannonballs. This bulwark, 25 feet wide, surrounded the bastion on three sides, separated from it by a dry moat, 20 feet deep and 35 feet across. All this had to be crossed before the French could reach the bastion itself, with sheer 40-foot walls of stone, and all that before they could cross a 25-foot drawbridge over the riverbank to the Tourelles itself.

“[The French] made the assault from all sides making every effort to take it, in such manner that they were before the Boulevard from morning till sunset without being able to take it or gain it,” recalled d’Aulon.

It was the bloodiest battle since Agincourt. The French came out from the city across the bridge to lay down timbers across the gap and menace the Tourelles from that side, and boatmen upstream filled a barge with flammables as a fireship, which jammed beneath the drawbridge, threatening to cut off the English on the riverbank. Meanwhile, every time they broke the English lines the French poured through en masse, but their tide came to a crashing halt at the foot of the bastion. “I was the first to set a ladder against the fortress on the bridge, and, as I raised it, I was wounded in the throat by a crossbow bolt,” said Joan.

The bolt penetrated “half-a-foot between the neck and the shoulder,” said Dunois.

Both sides must have thought it a fatal wound. The French quickly bore Joan off to the rear, even as the English cheered, “[We] killed the witch!”

“When she felt herself wounded, she was afraid, and wept,” recalled Father Pasquerel, admitting that some of the soldiers wished to use magic charms on the wound. “I would rather die than do what I know to be a sin,” Joan told them. She confessed herself to the priest.

“And the lords and captains who were with her, seeing that they could not well gain it [victory] this day, considering the hour, which was late, and that all were very tired and worn out, it was agreed amongst them to sound the retreat for the army; which was done,” said d’Aulon.

This occurred at about 8 pm, according to Dunois. “I was anxious that the army should retire into the town,” he said. “The Maid then came to me, praying me to wait yet a little longer.”

How this teenage girl could recover so quickly from a six-inch-deep wound is another of her miracles, but attested by many who witnessed it. Some accounts, likely apocryphal, even have her pulling out the bolt herself. “Saint Catherine comforted me greatly,” she said when asked about it later. “And I did not cease to ride and do my work.”

Joan then mounted her horse and rode to a vineyard where she remained by herself in prayer for about half an hour, according to Dunois.

D’Aulon remembered standing before the moat, “fatigued and worn out,” and handing Joan’s banner to a soldier named La Basque. But, fearing “by reason of the retreat, evil would ensue, and that the fort and Boulevard would remain in the hands of the enemy,” he asked La Basque to go down with him to the foot of the wall, hoping the troops would follow the flag. La Basque agreed, and d’Aulon, holding his shield over him against the rain of arrows and stones, led the way back down into the moat. He looked back to see the Basque still standing on the lip of the moat, flag in hand: “La Basque, is this what you promise me?”

But at that moment Joan returned to the fight. “Returning and seizing her banner by both hands, she placed herself on the edge of the trench,” said Dunois.

“Watch!” she told her men, waving the banner. “When you see the wind blow my banner against the bulwark, you shall take it!”

“At sight of her the English trembled, and were seized with sudden fear,” said Dunois. “Our people, on the contrary, took courage and began to mount and assail the Boulevard.”

“Be not afraid!” Joan told them. “The English will have no more power over you.”

The Basque took Joan’s standard and plunged into the moat with it, bearing it to the wall. “Joan, the tail [of the banner] touches it!” cried a man-at-arms.

“In, in, the place is yours!” said Joan.

By now no one on either side believed Joan could be defeated, or even killed. Some claimed to see the Archangel Michael and St. Aignan, patron saint of Orleans, riding in the sky.

“Glasdale, Glasdale, yield,” Joan shouted. “Yield to the King of Heaven. You have called me ‘whore’: I pity your soul and the souls of your men.”

As the French swarmed over the walls of the bastion the English within threw down their weapons. Glasdale and his knights made for the burning drawbridge to the gatehouse, but as they pounded across, it gave way. Glasdale fell into the Loire and, weighed down by his armor, drowned. “Joan, moved to pity at this sight, began to weep for the soul of Glasdale, and for all the others who, in great number, were drowned, at the same time as he,” recounted Father Pasquerel.

The English in the Tourelles surrendered. The drawbridge and bridge were repaired, and by torchlight Joan rode over them into the city that night. Church bells pealed. Hymns were sung. “The Maid and all the army were received with enthusiasm,” said Dunois, who rode at her side. “Joan was taken to her house, to receive the care which her wound required. When the surgeon had dressed it, she began to eat, contenting herself with four or five slices of bread dipped in wine and water, without, on that day, having eaten or drunk anything else.”

She could be forgiven her lack of celebration, for everyone knew the bulk of the English army was still out there beyond the wall. Another half-dozen bastions remained to be taken. Before sunrise the following day the English forces that were still situated on the plains around Orleans assembled before the trenches of the town.

Armed and armored, Joan rode out with Dunois and the French army beyond the wall, but forbade them to attack on a holy day. “At some points [they] were very near to each other for the space of an hour without touching each other,” stated the Journal. It was something that the French “submitted to with a very ill grace, obeying the will of the Maid.”

Suffolk and Talbot may have hoped the French knights could be goaded into making another ill-considered charge into the teeth of English longbows; failing that, they would not make such a charge themselves. “The hour being passed, the English set off and marched away, well ordered in their ranks … and raised and utterly abandoned the siege which they had maintained before Orleans since the twelfth day of October 1428 until that day,” stated the Journal. The siege had lasted seven months. Joan of Arc had ended it in seven days.

“I heard from the captains and soldiers who took part in the siege, that what had happened was a miracle; and that it was beyond man’s power,” said Alençon. Taking over as official commander of the French army, he nevertheless willingly took Joan’s advice. “In all she did, except in affairs of war, she was a very simple young girl; but for warlike things bearing the lance, assembling an army, ordering military operations, directing artillery, she was most skillful,” he said. “Every one wondered that she could act with as much wisdom and foresight as a captain who had fought for twenty or thirty years. It was above all in making use of artillery that she was so wonderful.”

There followed a strikingly quick chess match, played out in the Loire Valley. A little over a month after the relief of Orleans, the French captured Suffolk and half the English army by direct assault on the city of Jargeau, a dozen miles east. Five days later they took the bridge over the Loire at Meung-sur-Loire, 10 miles west of Orleans. By the time Fastolf belatedly marched from Paris, the English had 5,000 men, but so many French had flocked to Joan’s cause that they were nearly outnumbered. When she faced off with them near Beaugency, they backed down.

“The chief English captains in Beaugency saw that this Maiden’s fame had completely turned their own fortune, causing them to lose several towns and fortresses which had gone over to the enemy, some by attack and conquest, others by agreement,” said De Monstrelet. “Moreover, their men were mostly in a sorry state of fear and seemed to have lost their usual prudence in action. They wanted to withdraw into Normandy and their leaders did not know what to advise or to do.”

On June 18 the English retreated north. Near the village of Patay, learning the French were in close pursuit, they turned to make a stand. Seeing the English longbowmen set to work on their hedge of stakes, just as they had done at Crécy and Agincourt and the Herrings, d’Alençon asked Joan for advice. According to Dunois, she just said, “Have all of you good spurs?”

“What do you mean?” asked the captains. “Are we, then, to turn our backs?”

“Nay, it is the English who will not defend themselves, and will be beaten; and you must have good spurs to pursue them,” she said.

D’Alençon recalled that many of the French still dreaded English arrows, but Joan said, “In God’s name, we must fight them! Even if the English hang from the clouds, yet we shall have them! For God sends us to punish them. Today the gentle Dauphin will have the greatest victory he has won for a long time! My Voices have told me that the enemy will be ours.”

With that La Hire led the 1,500-strong French vanguard in a charge at full gallop. The English archers had no time to complete their hedge. They fled in a rabble, and the French knights cut them down. Burgundian mercenary Captain Jean de Wavrin, whose father had been killed fighting the English at Agincourt, fought in the English ranks; he saw Fastolf flee on horseback, to his disgrace. “And before he had gone, the French had thrown to the ground the lord de Talbot, had made him prisoner and all his men being dead, and were the French already so far advanced in the battle that they could at will take or kill whomsoever they wanted to,” said an eyewitness. “And finally the English were there undone at small loss to the French.”

The English lost 2,000 killed; French casualties were extremely light. De Coutes remembered Joan “had great compassion at such butchery. Seeing a Frenchman, who was charged with the convoy of certain English prisoners, strike one of them on the head in such manner that he was left for dead on the ground, she got down from her horse, had him confessed, supporting his head herself, comforting him to the best of her power.”

The destruction of the English army was complete. “After the deliverance of Orleans, and all these victories Joan went with the army to Tours, where the King was,” testified de Coutes. “There it was decided that the King should go to Reims for his consecration. The King left with the army, accompanied by Joan, and marched first to Troyes, which submitted; then to Chalons, which did the same; and last to Reims, where our King was crowned.”

Her work was done. “Many times in my presence Joan told the King she would last but one year and no more; and that he should consider how best to employ this year,” said D’Alençon.

In May 1430, a little over a year after her arrival at Orleans, Joan ventured out of Compiegne against the Burgundians when the drawbridge was raised behind her. Although accusations of treachery were made, they were never proved. The Burgundians captured her on May 23 and sold her to the English, who sealed her fate. Needing an excuse for their defeats, they had Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, who was an English sympathizer, try her in Rouen on charges of heresy and, when his inquisitors were unable to prove that, with dressing as a man. The outcome was never in doubt. “Wood was prepared for the burning before the preaching was finished or the sentence pronounced; and as soon as the sentence was read by the Bishop, without any interval, she was taken to the fire,” recalled court clerk Maugier Leparmentier.

A year and a week after her capture, 19-year-old Joan was burned at the stake on May 30, 1431. The executioner himself swore that at the moment of her death a white dove took wing toward France, and that her heart would not burn. The English scraped it up with her ashes and discarded both in the river Seine.

Cauchon died in 1442, but many of the witnesses at Joan’s first trial testified, albeit some rather uncomfortably, at her second trial. In June 1456 the Church proclaimed Joan of Arc not only innocent, but a martyr. In 1920 she was named a saint. She was the only person ever to be both condemned and canonized by the Catholic Church.

By then the people of France had long since raised her to the stature of a national heroine. Of all the personalities of the Middle Ages she is the most studied and well-known, yet her visions and miracles remain mysteries to this day, no better explained than by those who knew her best. “Neither I nor others, when we were with her, had ever an evil thought,” said Dunois, adding, “There was in her something divine.”