By Pat Reynolds

Suppose you found a magic door that opened onto some of the most crucial battles fought in the Pacific during World War II?

That’s the kind of door I stumbled upon in February 2010 when my 91-year-old father, Edward James Reynolds, died and left behind a diary that recounts nearly every day he spent as a radar man on the aircraft carrier Yorktown during World War II.

As I opened and read through this remarkable little gem, all kinds of questions surfaced. First, how did this book survive in such perfect condition? The guy served on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, for cryin’ out loud, where salt water, humidity, and rain were constants. And how did he manage to not miss a single day? We’re talking about approximately 545 days of entries, and they come from places as far flung as the Great Lakes Naval Base in Illinois, Virginia Beach, Central America, Pearl Harbor, New Guinea, the Marshall Islands, San Francisco, and sweet home Chicago at 1814 South Komensky Avenue.

And could this really be my father saying something like: “Arrived Pearl Harbor in afternoon. Impressed by Navy Band playing ‘Aloha’ as we pulled up to docks. Country beautiful. Women situation acute—125 men to every woman.”

Questions and curiosities aside, by the time I got to the part where my father laid eyes on the shiny new aircraft carrier that was about to propel him into harm’s way in the boundless blue, I was hooked. The diary became my way of experiencing the war vicariously. Gradually it dawned on me that his story belongs to everyone who benefited from his service in the Navy. If he and some 16 million other Americans had not stepped up to the plate the way they did, our lives would be profoundly different, and not in a positive way. So it is only fitting that the story of Ed Reynolds be shared, and shared as widely as possible.

What makes his story so compelling is that it turns the impersonal into the intensely personal. We all know from reading history books that Allied assaults on Japanese island strongholds in the Pacific—the Marshall Islands, the Gilbert Islands, the Marianas—were the beginning of the end for Japan in World War II. But what if we could be right beside a sailor from Chicago during these assaults? What if we could share his homesickness, his delight in new places, his fear of the ever-present danger that dive bombers and submarines and kamikazes represented, his pride in America’s military might and the rightness of its cause?

What if, through our Chicago sailor, we caught a glimpse of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet; of a ship’s captain who was the first Native American to graduate from the Naval Academy; of Pearl Harbor; of Pacific atolls and the natives inhabiting them? All of this is ours to share in Ed’s diary.

“Assigned to Yorkie”

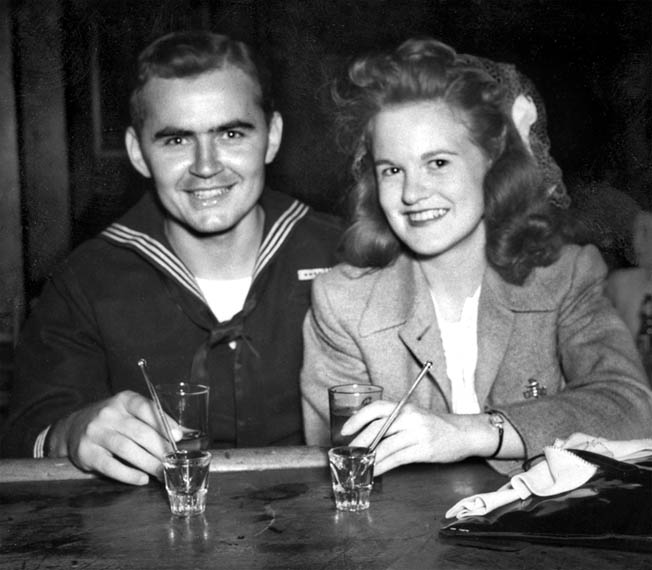

He begins in February 1943, when he writes that he is on leave from the Great Lakes Naval Training Base and has “nine heavenly days in Chicago.” A few days later, he leaves Great Lakes bound for Virginia Beach. “Lump in throat,” he tells us. “Will miss Chicago.” He leaves behind a 19-year-old neighborhood girl named Mary Ellen Murphy, who will surface repeatedly in the pages of his diary. Of all the reasons Ed looks forward to returning home after his Navy service, Mary tops the list.

Ed arrives in Virginia Beach March 13, 1943, and is bivouacked in the historic Cavalier Hotel. “Impressed by hotel’s beauty,” he notes. And well he might have been. Built in 1927, it was a masterpiece of architecture, sophisticated ambience, and gorgeous ocean views. So how did he wind up in such splendid digs? Because the U.S. Navy commandeered the Cavalier Hotel as a radar training school. Stables were cleaned and used as living quarters for some of the sailors, while in the swimming pool area the water was drained and the bottom of the swimming pool was used as a classroom. Imagine the Navy walking into Chicago’s Palmer House or New York’s Waldorf Astoria one day and saying, “We’ll be moving in now. And on your way out, drain that pool, will you? We may need it for something.”

By April 5, Ed finds himself five miles up the road at Camp Allen. “Assigned to Yorkie,” he notes. “Glad it’s a big ship, you don’t get so sick.”

This is Ed’s first reference to the USS Yorktown, the Essex-class aircraft carrier named to commemorate the first aircraft carrier Yorktown that was lost in June 1942 at the Battle of Midway.

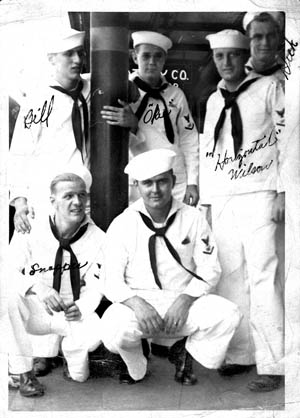

“It was nearly the length of three football fields,” he always used to tell us when we were kids, and sure enough, the Yorktown was 820 feet long. I should say is 820 feet long—it is now docked at Patriot’s Point near Charleston, South Carolina. Its crew numbered 380 officers, 3,088 enlisted personnel, and 90 planes. It was commissioned on April 15, 1943, as Ed duly notes in his diary. Shortly after the commissioning ceremony, Ed and about 3,400 of his newfound comrades introduced this historic ship to sea.

Arrival in Hawaii

A “shakedown” cruise to Trinidad included beer parties on the beach financed by the 20th Century Fox Studios. June 17 has the Yorktown back at the Navy base in Norfolk, Virginia. The same evening, Ed departs on leave for “four days of happiness” back in the old Chicago neighborhood. Unfortunately, he returns from Chicago to the Yorktown six and a half hours “over leave,” which leads to this June 22-23 entry: “Spent these days ‘over the side,’ airgun in hand, scraping the bottom of the ship. Miserable duty.”

By July 7, with the Yorktown on its way to Pearl Harbor by way of the Panama Canal, Ed notes, “Scout planes spotted two subs.” The next day his entry talks about three “cans”––Navy slang for destroyers. These are the Dashiell, the McKee, and the Terry, and they show the way, writes Ed, “through sub-infested & squall-swept waters.” He also notes that he spent some time on July 8 in the pilot house, which causes him to observe that “the capt. is some character.” It’s worth noting that the captain he refers to is “Jocko” Clark, or Admiral Joseph J. Clark. Born in Oklahoma and a member of the Cherokee tribe, he was the first Native American to come through the U.S. Naval Academy.

While in the vicinity of the Panama Canal, Ed notes sighting Costa Rica and El Salvador. Once through the Canal and sailing west through the Pacific, he writes that the coast of Mexico is 200 miles away. “Issuing steel helmets & gas masks,” he notes. By now, thoughts of home are never far away. “Beautiful moonlit night. Flight deck would be wonderful spot for a dance. Heard ship’s orchestra practice—wow, are they solid.” And the next day: “All afternoon on flight deck gazing out over the water, thinking of home.” And a few days later: “Realization I’m a long way from Komensky Ave. When will I get to see Chicago again? No mail. Just plain lonesome tonight.”

Throughout the loneliness and homesickness, one thing that clearly appeals to him is the thought of being in Hawaii. Remember, he has never been farther from 18th and Komensky than Fox Lake, Illinois. So imagine his sense of anticipation when he writes: “Hawaii just 300 m dead ahead. Swaying palms, make way for E.J.”

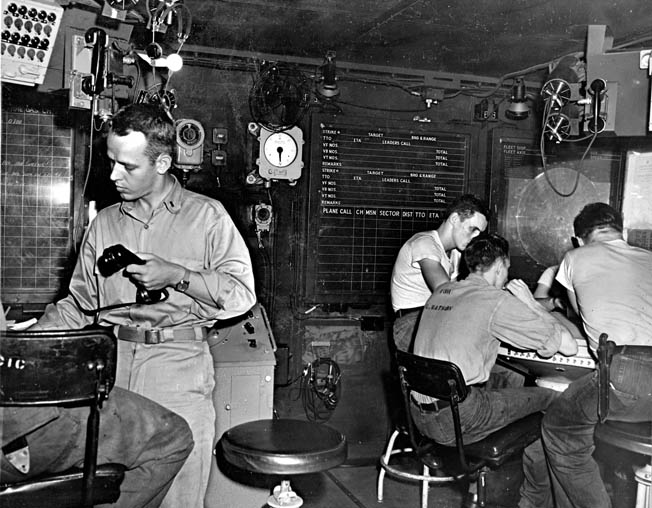

When the Yorktown does reach Hawaii, it’s still four nights before E.J. gets up close and personal with those swaying palms. “Wish I could go ashore & just wander around on that mountain range to the West,” he writes. Keep in mind that he’s never seen a palm tree in his life at this point. In the meantime, he rubs shoulders with none other than Chester W. Nimitz, the commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. “Anticipating tomorrow’s visit to Honolulu. Up in Radar Plot working tracking problem when Adm. Nimitz came through on inspection tour. Com. of Pac. Fleet is a nice old boy.” He then adds: “Boxed in evening, ran into a stiff left.”

Eventually Ed does get to see Honolulu, and he enjoys it a lot, especially Waikiki Beach, the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, an aquarium and bird collection, tennis, bowling for a nickel a lane, and pool. On August 21 he writes, “Liberty with Small & Furlow. Ping-pong & pool at U.S.O. It’s surprising how much food 3 guys can eat.” By August 22 it’s anchors aweigh from Pearl Harbor. “Rendezvous with task force,” he writes. “18 ships strong headed for Jap. held Marcus Islands.”

“Dog Day”

From here on, the diary entries grow ominous, to say the least. On August 30, he writes: “Exec’s message on eve of attack: ‘Tomorrow morning we will commence to launch attacks on Marcus which will be repeated again & again until all Japanese in the vicinity have been destroyed.’ ”

On August 31, which Ed calls “Dog Day,” war enters the lives of both Ed and the Yorktown: “Reveille 0200. We attack in 6 waves. First planes leave Yorkie 0420. First contact 0600. Japs report they’re under air attack at 0620. Many fires. Sampan strafed, left in flames. Radio installations knocked out. 35% of Marcus destroyed. Yorkie lost 2 F6F’s & 1 T.B.F. & 5 men. We were put into two emergency turns of 60 degrees because of sub. contacts. Our guns manned all day. Didn’t fire a shot. Underway for Pearl at 1800.”

Why the Yorktown makes such a sudden detour from battle—its very first battle—is never made clear. But for the next 14 days, all diary entries describe the Yorktown’s passage back to Pearl Harbor, from there to San Francisco, then back to Pearl again, and then off to attack Wake Island. While not so interesting from the military historian’s point of view, this 14-day period is filled with unique glimpses into what it meant to be a sailor on board an aircraft carrier in the middle of World War II. Again, it is fascinating to read one man’s observations, reactions, and inner thoughts juxtaposed against the drumbeat of all-impersonal history:

“Just a little closer to that 2 wks. accumulation of mail at Pearl Harbor.

“Whipped out a few letters. Sack time.

“Sun bath on flight deck. Saw a bird—land not too far distant now. “Pearl” & promise of liberty tomorrow—good duty. Night trials for pilots.

“Moored at Pearl. Welcoming band played ‘Aloha.’ Nice. Watched school of fish frolicking off the starboard side as we moored.

“Turkey dinner. Received 16 letters. Swell day aboard.

“Underway for Frisco at 1430. Essex leading the way. Abandon destroyer escort 75 m. out.

“Just us & Essex. Hauling ass unescorted.

“Moored starboard side just aft of Lexington at 1600. Nice to be back at Pearl. Kid struck by prop in hangar deck.

“All morning sunbath on flight deck. Wonderful this weather.

“Day closer to Dog Day at ‘Wake.’”

You can only shake your head and wonder what happened to the poor guy who got struck by a prop in the hangar deck.

Eventually Wake Island is in range. Ed writes on October 4, 1943, “2 Bogey contacts. Impending danger sign. Marine shining up dog tags.” Which is the danger sign, the Bogeys or the Marine polishing his dog tags? But the attack on Wake goes well: “0610 report says attack a complete surprise. Cruisers shelled Wake. Yorktown loss: 3 planes, 2 men. Jap loss: 17 planes on the ground left burning, 13 shot out of the sky.”

The attack continues on October 6: “Sent in our bombers from Midway. More strikes from task force. Loss for the day: 6 planes, men. Capt. says to crew, ‘Congratulations, best day Yorkie has ever had.’ ”

Probably not so good for the men who lost their lives.

“The Perfect Liberty”

From Wake it’s back to Pearl and some liberty that includes bicycling in the hills above Honolulu. His descriptions of liberty are priceless little snippets of relaxation and release from the stresses of war. First, there were 18 holes of golf at Waialae Country club with Snapper, Small, and Gus followed by a “swell” meal. “The perfect liberty,” writes Ed. Three days later, eight of them are back on the golf course, and this time some photos are shot. “Four rolls of pictures, including 2 shots of me in shower wearing nothing more than my newly acquired suntan.”

But it’s back to war by November 10. “Meeting of our unit discloses the seriousness of this mission,” Ed writes. “Our new Exec Mr. Briggs warned us in Radar Plot against doping off now that we are approaching the Japs’ sector searches. Exec says they know we’re coming & not to expect a song & dance affair as was experienced at Marcus & Wake.” And the next day: “Out to raise hell in the Gilbert Islands.”

Unfortunately, the hot, humid weather raises hell with Ed’s skin: “Sure hope the sick-bay-prescribed cal-o-mine lotion will in some way reduce the heat rash I have spread over even the least talked-about parts of my anatomy.” Apparently his heat-induced skin rashes cause him to take a less than official approach to garb one day. “Captain had no patience at all with my non-regulation apparel up at Pilot House Sunday night. ‘Out, out!’ Yes, I went out, but fast.”

An Ordinary Man at War

The passage below is presented without editorial interruption because I think its immediacy and intensity best shine through that way. This is what it’s like for an ordinary man to be at war. We’ll circle back at the end for some explication, a term most often used by literary critics who tease out the elusive meanings of poetry. I find the term “explication” appropriate in talking about Ed’s diary, too, because it reads a little like an epic poem, with Mary cast as the patient Penelope and Ed as the wandering and war-tossed Ulysses. One definition I will provide up front: GQ stands for General Quarters, which means be alert for battle conditions.

“November 17: Word was passed forequarters this morning to ‘pray the dead.’ The ceremonies were for 23-year-old N. Carolinian P.M. Second Class Rayford, who died of a heart attack last night. With the entire crew standing at attention on the flight deck, he was committed to the deep as the flag-clad canvas bag was slipped over the Starboard Side Forward to the gun salute of the Marines.

“We are now in the approach area, in waters subject to submarine & air attack. Squared away my preserver, gas mask, & flash clothing up in radar plot.

“November 18: Haulin ass for our operation point at Southern tip of Marshalls, where it will be our job to cruise up & down in the slot between Marshalls & Gilberts, protecting operations to our south.

“November 19, Dog Day: GQ 0420. Launch first of 9 strikes. Hit Makin, Jaluit, Milli, & Tarawa. Very little resistance encountered.

“November 20: Continued attack on islands. Land 6 divisions of Marines & tanks on Tarawa. Considerable resistance. Soldiers establish beach head on Makin. Jaluit attack destroyed 13 sea planes, 1 AK & 2 boats. Planes, though well strafed, did not burn. When AK was left, decks were awash. Report at 1320 that Adm. Turner’s outfit to the south of us is under attack by several Bettys.

who died of a heart attack aboard the Yorktown on November 16, 1943.

“November 21, D+2: GQ 0315 because of four Bogey contacts on radar. One bogey passed within 8 m of the cloud-secluded, slow-moving Yorkie—we’re cut down to 12 knots to reduce wakes. Broke radio silence for short transmission by Commander in Chief of our task force, Capt. Hedington: ‘Bogeys on the way.’ Thanks to the good Man above for no night attack.

“Radio dispatch: ‘In an attack at dusk last evening, the Independence was ‘tin fished’ when attacked by 15 Bettys.’ They came in low and were not detected by Radar. We splashed one Betty 52 miles astern of us on single-vector perfect interception by Lt. Stover. Periscope sighted by USS Cowpens at 1304. It’s wide awake we’ll be at dusk tonight. No mass today, don’t seem like Sunday.

“November 23, D+4: 1030 Bogey contact at 330 Deg. 90 M.I. Fighters vectored out by Lexington Interception at 45 Mi. We splash 15 of 20 Zeros. Our own loss: three planes—only one as a result of engagement. No men lost. Picked up 5 [from] Liscome Bay. Fighters Lost. Just at dusk. She was operating somewhere South of us. We landed 3 of the F4Fs, & the fourth attempted landing resulted in an awful crash & fire that cost 5 men their lives while injuring 3.

“November 24, D+5: Burial services for our 5 lost shipmates in morning. “Baldy” reports Liscome Bay was lost yesterday as the result of either a torpedo or an explosion. I knew “Whitey” Kaskman, he used to pour the “Joe” in the aftermess hall where I often ate.

“GQ alert at 1240. Just when I was eating chow, large Bogey at 90 m. Interception by Lexington’s fighters at 55 m. Bogeys stacked & in two layers Ag 23 & 27. Our fighters at Ag 25. Splashed 9 Zeros, 1 Betty. Chased 2 Bettys, 1 Zero. Raid dispersed. Our loss: 1 fighter shot down in flames by 3 Zeroes.

And now for that explication: “Tin fish” is a torpedo. As for “splashed,” it means shot down. “Bogey,” of course, is an enemy aircraft whose specific type or class has not been identified. Bogeys were very much on the mind of Radarman Third Class Ed Reynolds because a chief responsibility of the radarmen was to know where enemy aircraft were at all times.

Makin, Jaluit, Milli, and Tarawa are all islands in the Gilbert or Marshall chains. Tarawa was an atoll with a garrison commanded by Kaigun Shosho Keiji Shibasaki, who had boasted before the invasion, “It would take one million men one hundred years” to conquer Tarawa.

Shibasaki was slightly off on his 100 years boast; it took only 72 hours. But when Ed reports that the Marine invasion of Tarawa met with “considerable resistance,” it was some kind of understatement. After 72 hours of intense fighting, some 6,000 men died, and 1,667 of them were Americans, mostly Marines. Back in the States after the battle, protests mounted when the casualties were reported. Writing after the war, when Marine General Holland M. Smith was asked if Tarawa was worth it, he didn’t mince words. “My answer is unqualified: No. From the very beginning the decision of the Joint Chiefs to seize Tarawa was a mistake.”

Regarding the term “Bettys,” it’s an Allied code name for one of the many Japanese war planes that had to be dealt with. The Betty is one of several dive bombers that the Japanese air force brought to the table. Zeros, the advanced carrier-launched fighter planes developed by Mitsubishi for the Japanese Air Force during the war, were “Zekes.” Other names included “Nell” (an attack bomber), “Kate” (a carrier-launched attack bomber), and “Dave” (reconnaissance seaplane).

The Sinking of the Liscombe Bay

The explication most helpful in appreciating what Ed experienced regards the sinking of the Liscome Bay, an escort carrier capable of carrying 28 planes. It was sunk by a Japanese submarine torpedo and went down in an explosion so intense that flesh and debris were showered onto the battleship USS New Mexico, a mile away. One sailor on the destroyer USS Hoel described the incident this way: “It didn’t look like a ship at all. We thought it was an ammunition dump. She just went whoom—an orange ball of flame.” She went down in 23 minutes, and with her went 644 officers and men. U.S. ships in the area did manage to save 272 of her crew.

Armed with this information, it would appear that when Ed writes “Picked up 5 Liscombe Bay. Fighters Lost. Just at dusk,” he means that at dusk the Yorktown radarmen picked up five planes trying to find their way to a Liscome Bay that was already at the bottom of the ocean. Of the five planes, four made safe landings on the Yorktown, but one crashed, killing five and injuring three. Ed mourns the loss of “Whitey” Kaskman, who appears to be one of the five Yorktown men who lost their lives in the crash on the flight deck.

Attack on Kwajalein

With three major battles under her belt, the Yorktown now moves toward its next target: the island of Kwajalein in the Marshall chain. Located 2,100 miles southwest of Honolulu, Kwajalein is the world’s largest coral atoll as measured by area of enclosed water. Heavily fortified and a key piece of the Japanese perimeter of defense, Kwajalein was used as an outlying base for submarines and surface warships.

November 25 brings Thanksgiving and a “wonderful turkey dinner,” writes Ed. “Thanksgiving, & quite a bit to be thankful for.” On midnight watch two days later, he worries about collisions and “closely formed task forces almost running into one another.” The heat bothers him, so he sleeps on the flight deck instead of his bunk. A day later, he wonders about the rumor of transfers, which gets him to thinking about home. “How about Komensky Ave.—will I see it soon?”

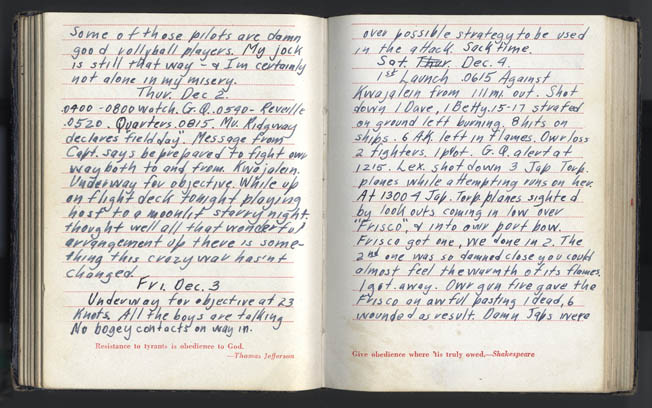

Captain Jocko Clark, on the other hand, is more focused on the task at hand. “Message from Capt. says be prepared to fight our way both to and from Kwajalein.” And then my favorite moment in the entire diary: “While up on flight deck tonight playing host to a moonlit starry night, I thought, well, all that wonderful arrangement up there is something this crazy war hasn’t changed.”

The attack on Kwajalein commences December 4, and once again I think Ed’s entry says all that needs to be said:

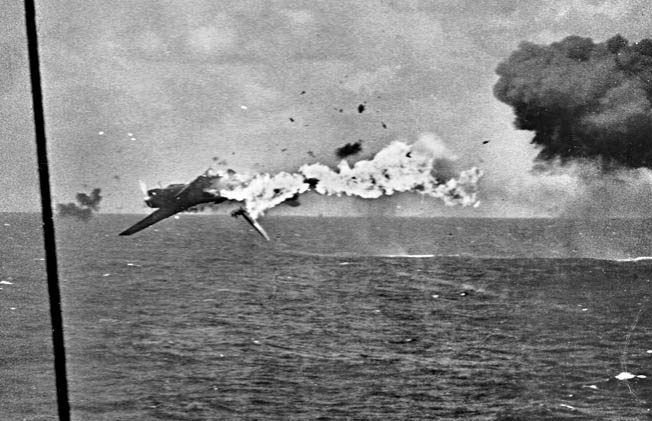

“December 4: 1st launch 0615 against Kwajalein from 111 mi. out. Shot down 1 Dave, 1 Betty. 15-17 strafed on ground left burning. 8 hits on ships. 6 AK left in flames. Our loss 2 fighters, 1 pilot. Lexington shot down 3 Jap torpedo planes while attempting runs on her. At 1300, four Jap torpedo planes sighted by lookouts coming in low over the San Francisco & into our port bow. Frisco got one, we done in 2. The 2nd one was so damned close you could almost feel the warmth of its flames. One got away. Our gunfire gave the Frisco an awful pasting. 1 dead, 6 wounded as a result. Damn Japs were strafing too as they came in.

“Wotje Island strike almost abandoned to supply additional fighters to repel torpedo attack. Wotje strike got 3 Bettys, 2 Zekes; hangars & oil stores left in flames. Oil slick near large cargo vessel subjected to near miss. Jap snooper reports our position. GQ alert at 1900. Bogies all over the place, looks like a hell of a night. Clear moonlit night & that doesn’t help matters. Smoked a fag given me by radioman “Red.” Constant stream of sandwiches & drinks for the officers. Don’t that fry my ass. Bogeys all disband at 2230. They formed again to start new attack at 2315. They can see us but we can’t see them damn it all. We fire spasmodically when they get in close, just can’t connect. Lexington got one in starboard quarter at 2330. Lexington still able to turn over 18 knots. Steering gear out. Lexington will be guided in by a Can. Those 5-inchers really make a racket.”

Recreation on the Yorktown

With Kwajalein in her rear view mirror—for the time being—the Yorktown heads back to Pearl Harbor. Movies onboard during this time include Granny Get Your Gun and The Kid Glove Killer. The latter, says Ed, is “cool.” Back in Pearl, the days include tennis and ping-pong tournaments and the movie The Human Comedy (“What a movie,” says Ed).

When rumors of a possible return to the States surface, he writes, “Maybe it will be Fox Lake in the Springtime for E.J.” He was crazy about the Chain of Lakes just north and west of Chicago, where his mother had a cottage on Fox Lake. Christmas comes and goes. “Takes a hell of a lot more than good chow & a Christmas tree to make a Christmas,” Ed notes.

On January 15 the Yorktown is underway at 12:45 pm, headed back to the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. All of this activity, it should be noted, was part of the United States’ strategy known as “island hopping.” Admiral Chester W. Nimitz executed this strategy in the central Pacific, while General Douglas McArthur, commander of the Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific, took responsibility for the South Pacific. The idea was to establish a line of island bases close enough to Japan so that American bombers could launch from these islands and reach the Japanese mainland.

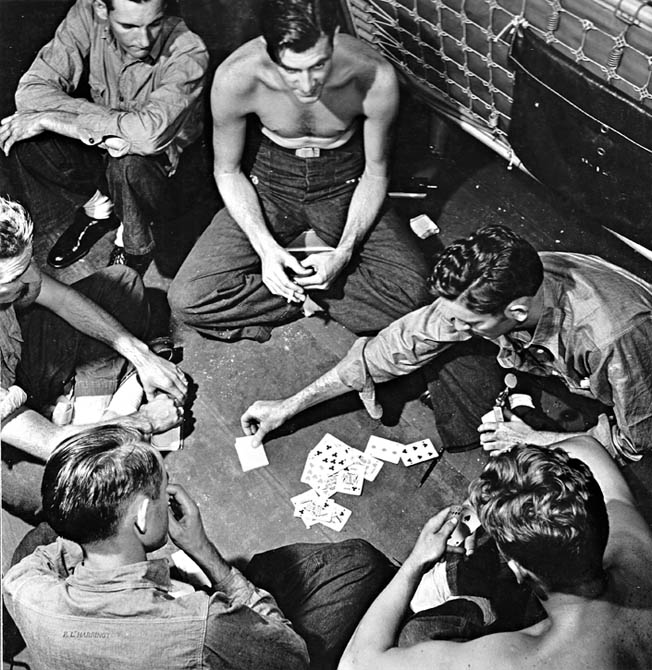

Despite the grimness of this task and the number of lives it cost, life onboard the Yorktown wasn’t without its lighter moments. Ed writes of the long-standing naval ceremony that takes place when the ship crosses the Equator and the “pollywogs” (sailors who have not previously crossed the Equator) become “shellbacks” (fit subjects of King Neptune). It’s basically a bunch of good-natured hazing. Ed is one of the sailors who makes the transition from pollywog to shellback.

“January 21: The pollywogs began to play this afternoon on the flight deck. All one guy had on was a large diaper. That boy in pink panties & brassiere sure looked good. How about those poor jerks dressed in those warm fur-lined high-altitude clothes. Lt. Coms. Lambert & Earnshaw sure looked silly dressed in divers gear. And the fighter pilots ran down the deck strafing with beans. Capt. Clark’s usually stern face was lit up with an ear-to-ear smile as he watched the show from the bridge.

“January 22: We all have one thing very much in common tonight & that is a very sore butt, as the result of initiation into the “shellbacks.” Nice to have become a shellback without having my hair dug out in spots or being rolled in the garbage box.”

As he does throughout his time in the Pacific, especially when near the Equator, Ed rails about the heat: “I’d give a hell of a lot for a nonperspiring night’s sleep at that Komensky Ave. shack.”

Majuro lagoon

From January 29 to February 4, 1944, the Yorktown and its planes return to Kwajalein, while other U.S. task forces attack the islands of Roi, Eniwetok, and Wotje, all in the Marshall Islands. In the battle of Kwjalein, 7,870 of 8,000 Japanese soldiers died, while American losses were 372.

By February 4, the Yorktown is anchored in the lagoon of a gorgeous tropical atoll called Majuro. Ed describes it as “tiny islets of coral, with coconut palms & grass shacks. Sure would love to go ashore & browse. Supposed to be 900 natives housed on this U-shaped atoll.” A day later he writes, “A peaceful day in a sleepy lagoon. Mail, wonderful mail. Cool, quiet—nice.” More mail arrives on February 6, and Ed attends Mass with Dan Murphy, the brother of Mary who waits back home.

All Ed’s entries while in Majuro are peaceful, almost idyllic. “Don’t those natives go like hell in an outrigger canoe with sail. Temperature ideal, breeze constant. It’s nice out here.” But he is also constantly aware that this is only one of those calms before a storm: “What a tremendous amount of power sitting around out here. Five big flat-tops, one right next to the other & about a mile apart. Enterprise, us, Essex, Intrepid, & Bunker Hill.”

On February 9 he writes of a “dip in the lovely blue waters of Majuro.” But again, he knows this island paradise is only a brief respite: “How long are we going to stay in this place? If our next objective is Truk, maybe the peace & quiet of Majuro should be appreciated.” He also makes it clear that even island paradises have their downsides: “Major engagement with jellyfish while swimming in 33 fathoms of Majuro blue.”

On February 11 he notes that it is the Yorktown’s last day in the lagoon. After lights-out, he has what he calls an “after it’s over session with Furlow & Weeg.” I would imagine such sessions were a constant source of comfort to countless servicemen who were able to find refuge from the stress and mayhem of war by sitting down next to a comrade and saying, “Here’s what I’m going to do when this thing is over.” Sadly, plenty of servicemen—on both sides of the conflict—never made it to the days when the war was over.

Combat Stress on the Yorktown

Leaving Majuro lagoon at 9:30 am on February 12, Ed learns it is indeed the well-fortified island of Truk in the Caroline Islands that the Yorktown will tackle next. A major Japanese logistical base, it was something like the Japanese equivalent of the U.S. Navy’s Pearl Harbor. “Sounds like a very daring operation,” he notes. “Rough sea. Focksle [sic] awash. This damn heat & continued perspiring has me full of heat rash again.” But he is thankful for small—or not so small—favors: “No bogeys.”

On February 16 he reports, “Our score for the day: shot down in the air 25 planes, on the ground 8 planes, 4 probable. Many hits on our cruisers, destroyers, & cargo ships.” He also says a friend named Smoky was down in a life raft but that a submarine had a fix on his position. “Hope he was picked up,” says Ed. The tail gunner of a badly shot up Yorktown bomber is not so lucky, however, and dies aboard the ship. Ed’s summary: “Long, bogey-crammed day.”

February 18 brings this entry: “Hauling ass from Truk.” The Yorktown’s next target is the island of Saipan in the Marianas chain, where a bomb drops 100 feet off the starboard bow. “It was exactly the kind of day you read about but not the kind you ever expect to actually experience. Planes falling on all sides of our group. Coming in just one or two at a time, they were just duck soup for our gunners. Can’t understand their strategy, if you can call it that.”

February 25 has the Yorktown headed back to Majuro, and it appears that the constant stress of battle is beginning to take its toll: “Our gang could sure use some leave. Not a day goes by anymore when we don’t have a serious argument or near fight. We’re all getting touchy, irritable, & less tolerant. Variety is the spice of life & there’s damn little seasoning we get.”

Four days later, still in Majuro: “Still sitting, waiting, and wondering about our next move.” But the good news is that “beach parties” are being arranged for small groups at a time, and on March 3 it’s Ed’s turn. He and a fellow named “Crotch” have a great day. “Swimming, we see beautifully formed & colored coral. Pabst in cans, sandwiches—really swell. Wandered from one island to the next. Signs of where the Japs were dug in—and then dug out.”

On March 8 at 8:00 am, the Yorktown is underway once again, this time headed for Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides archipelago. A military supply base, naval harbor, and airfield, Espiritu Santo is generally known as the inspiration for James Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific, which in turn was the source for the Broadway classic South Pacific. Some new pollywogs are given the shellback treatment as the ship crosses the Equator on March 11.

Ed’s introspective side surfaces in a Sunday entry: “Every evidence that the sea is observing the Sabbath, judging from its very calm surface.” But he’s a little miffed to hear about the “revelation” that 90 percent of the shells available for use by the Yorktown’s five-inch guns were duds. “What a hell of a lot of protection we wouldn’t have had had we needed it at Saipan,” he writes.

They “drop hook” (anchor) in Espiritu Santo on March 13, and he is not happy about how hot it is: “Every indication that impetigo, ring worm, & the variety of heat rashes we have onboard will really thrive out here.” But there is good news, too: “107 sacks of mail. Wonderful stuff.”

Beach parties resume at Espiritu Santo, and he sees a USO show featuring Ray Milland and Mary Elliot. He also happily reports that the dud shells for the five-inchers are unloaded. He sees Girl Crazy and notes it stars Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. He also describes some of the local marine life: “Strange companions off bow. Large turtle, with two sandsharks depending on him for shade. Large schools of fish raising hell with minnows.”

“Sunset Bogeys”

Scuttlebutt says that the next target for the Yorktown is the Caroline Islands, and as other task forces join his, he’s impressed by the combined firepower they bring: “95 to 105 ships in all, what a powerhouse, including Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Hornet, Lexington, & us.”

But it’s not the Caroline Islands––it’s the island of Palau they’re headed for. Some good news, too, for our Chicago sailor: “Ridgeway says this is the last operation and then Majuro & Frisco & finally Chicago—wonderful Chicago.”

By March 29, the attack on Palau is underway, and Ed notes that the Japanese dive bombers are flying so low that radar contact is difficult to fix. He also notes, “I’m counting on that ‘operating under a spiritual umbrella’ that Father Farrell referred to. We’ll need ‘his’ protection tonight.” Later that day, after concerns about “sunset Bogeys,” he writes: “Escaped unscathed—good old ‘umbrella.’”

On March 31, the Lexington radar crew picks up a sampan in the predawn hours. “Investigation with a searchlight revealed Jap insignia. Sunk same. Made wonderful glow on horizon.” He also reports on the fate of a life raft of U.S. airmen whose plane has gone down. “A Zeke strafing survivors in a life raft was chased & splashed by two of our V.F.s. Life raft survivors unscathed.”

One more note, and a sad one at that, before the Yorktown leaves Palau. There are still about 100 American servicemen listed as missing in action there.

“No Saturday. Passed Time Zone, Gained a day.”

The Yorktown next launches its planes against the island of Woleai in the Carolines on April 1 from 140 miles out. Encountering “no fighter opposition,” the ship then heads back to Majuro. “Scuttlebutt says Majuro, Pearl, then Frisco—oh, how I hope it’s good dope,” says Ed.

On April 7, after a basketball game on the hangar deck, Ed writes sympathetically about the fate of his friends whose girls back home have not been true. “Bogie got news his Arline is getting married. That makes Ward, Geres, Nelson & the Bogie who all belong to the brush-off club.” More bad news comes on Easter Sunday, April 9, when it becomes clear that the aforementioned “dope” was not so good after all: “At Majuro. 0645 Mass. Loading ammunition—that settles the States deal.”

Ed and crew are still in Majuro on April 12 when he gets called from a football session on the flight deck to take his Radarman Second Class test. He is clearly getting more than anxious to get back home, and his April 13 entry shows that he has grown skeptical of any news suggesting that home is a possibility anytime soon. “Pow-wow. ‘Ridge’ says we’re covering the invasion of Hollandia in New Guinea. ‘Frisco after this one,’ says Ridge. I don’t find that line funny anymore.”

A day or so later is one of those entries that’s fascinating because it demonstrates how meticulous Ed was when it came to entries in his diary. Between his Friday, April 14 entry and his Sunday, April 16 entry he writes: “No Saturday. Passed time zone, gained a day.” It’s as if he knew someone would be reading his observations one day in the future, so he wants to make sure that whoever that someone is, they won’t be able to accuse him of missing a Saturday entry.

With the Yorktown en route to Hollandia, we learn that “Pinkie” is in sickbay with South Pacific “complection,” whatever that is, and “Dewdrop” is also in sickbay with impetigo. “Nothing to do & lots of time to do it in,” writes Ed. “Too damned routine. Take me back to that Komensky Ave. shack.”

When the Yorktown reaches New Guinea, they hit Wakde Island rather than Hollandia. Ed explains: “Got word the Japs had more planes there.”

April 22 brings a rather cryptic entry describing the crash of a Yorktown torpedo bomber: “Pre-dawn launch T.B.F. 10 crashed N. Orleans on takeoff. Fouled up. Radar antennaes, killed plane crew & 1 N.O. sailor & injured one N.O. sailor, when bombs exploded.” A little research on the USS New Orleans, a heavy cruiser, tells us that this is what happened: “On 22 April a disabled Yorktown plane flew into New Orleans’ mainmast, hitting gun mounts as it fell into the sea. The ship was sprayed with gas as the plane exploded on hitting the water; one crewmember was lost, another badly hurt.”

The April 22 entry also includes a reference to General McArthur: “Army (under direction of Gen. ‘Mac,’ who was upon the bridge of a cruiser) made landings at Humbolt Bay supported by our air group.”

Strikes on Truk continued through April 30, and an entry on that day reminds us that submarines from both sides of the conflict were ever present. “Sub. made daring rescue of 8 of our pilots down in life rafts near targets. Screen destroyers picked up surfaced enemy sub. Ganged up with planes to knock the hell out of it. Oil slick, underwater explosion, & telltale flotsam confirmed sinking.”

By May 1 it’s back to Majuro “with a stopover for a few strikes at Ponape,” writes Ed, adding, “Finally got that second stripe.” Home is really beckoning by now: “More of that stuff about our trip to Pearl & then those Golden Gates—nice dreaming. Wait for me Mary—ironical & true.” But there’s still no guarantee about heading home. “Opinion now divided as to whether it will be Frisco or a change of squadrons at Pearl & then ‘just one more raid.’ ”

Ed also spends more time worrying about his Mary back home. “Lost pen upon focsle [sic] last night while crapped out up there—damn it. Lost the Mary-sent bracelet, now the pen. Say, maybe by this time I’ve lost the donor of these gifts as well.”

When the Yorktown reaches Pearl Harbor, initial scuttlebutt has the ship executing “just one more” mission before heading for the mainland. But some continue to believe there won’t be another mission, that home is around the corner.

“The poor dopes,” writes Ed. “I don’t think I’ll ever believe another word given to me while I’m in this outfit. From now on, ‘I’m from Missouri.’” His skepticism, it turns out, is well founded. He winds up getting assigned as radar school instructor for six months at Catlin Park Military Complex in Pearl Harbor. But there are some good things: “This fresh milk sure is wonderful stuff. Yorktown, I don’t think I’ll miss you very much.” And later, “Burk & I spent the evening admiring a beautiful horizon to the Northeast. Gave me kind of a nice homey feeling. Life out on the blue just doesn’t compare with shore duty.”

Ed manages to collide with another player in a baseball game on June 9, which results in a “metal clip in chin.” He has the clip removed June 12, he tells us, and he adds this poignant detail as well: “This old fart Stokes that sleeps above me sure makes a racket with his combined farting, snoring, and grinding his teeth.” On a slightly more romantic note, he adds: “Thinking of Mary an awful lot.”

On June 15, Ed goes aboard the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid. He notes: “Strange how a smile developed on my face as my feet struck the rather familiar hangar deck of the Intrepid. I guess you do develop a certain amount of sentimentalness after making one your home for 14 months.”

Another kind of “sentimentalness” is also constantly referred to: “Seeing guys and gals together sure makes me think in terms of Komensky Ave.” And then there’s this: “At Catlin & liking it. Time passes so swiftly I seldom have time to keep up this little book of memories.”

A few days after Ed’s July 12 entry about seeing the Bob Hope show at Maluhia, he runs out of space in his diary. So he starts a new one, nearly identical in appearance as the first but this time a softcover version. Needless to say, he does not miss a day. The original ends July 14. The new one begins July 15. Big news on July 17: “Word that Burke, Reynolds, Dekart, Marqus, Brandt to make homeward trek come Aug. 1st. Wonderful—ah, yes, wonderful. Thinking lots these days in terms of Komensky Ave. & Mary.”

He notes that President Franklin D. Roosevelt comes through Catlin on July 27, but it hardly registers: “As Aug. 1st comes closer, I can think of nothing but home.” Not that he won’t miss the beauty of Hawaii: “I’ll miss the soft air, the gardenia scent when passing the lei vendor in front of the Moana Hotel. I’ll miss the purple red sunsets, wonderful cool evenings. It has been nice.”

By August 3, Ed is on a troop transport ship pulling out of Honolulu bound for San Francisco. Onboard with him are a number of wounded sailors, soldiers, Marines, and civilians. Their presence reminds him of how fortunate he has been. “Surely do thank the good Man above whenever I see that sailor without the chin or the Marine without legs—or hell, any number of the many casualties we’re taking Stateside.” The next day his entry is a little less spiritual: “Invested in one of the many crap games on board—fine investment.”

After spending August 8 in San Francisco, Ed boards the Union Pacific’s Challenger for a three-day ride to Chicago. “Chicagee, stand by,” he writes on August 10. Next day: “This vehicle just can’t go fast enough to please me. Neighboring soldiers still have enough quarts to go around.” Finally, on Saturday August 12, the entry he’s been aching to make: “Arrived C. & N.W. station 11:20 am. Taxi ride home. Home wonderful home.”

Once back at 18th and Komensky, he makes an August 13 entry. I must confess, considering all he has been through, the dangers he has survived, and the promising young lives he’s seen snuffed, I fight back tears every time I read it: “Raced Ann all the way to Finbarrs. Strangely enough we arrived on time for 12 o’clock Mass. Father McKenney, Marty, the Brusts—oh hell but it’s swell just saying hellos to guys & gals you haven’t seen for awhile.”

Returning Home After 538 Entries

And that’s it. After 538 days of entries, the next page and all the pages after it are perfectly blank. There were no more diary entries for Ed. I guess he was too busy living.

Ed stayed in the Navy for another 14 months, training radar operators at Great Lakes Naval Base back in Illinois, the very place where his military odyssey began. His discharge papers tell us he exited the Navy on October 1, 1945.

As for Ed and Mary, they were joined in matrimony on May 22, 1948. The wedding was at St. Finbarr’s, not far from that Komensky Ave. shack about which Ed had fantasized while at sea. Ed and Mary had seven children and nine grandchildren, and Ed lived to see one great grandson.

Careerwise, Ed returned to the Cicero, Illinois-based Western Electric Company where he had worked for two years prior to his service in the Navy. By the time he retired from that telephone manufacturing monopoly, he had 43 years under his belt. In the 1950s, Ed and family moved to the town of Lombard in Chicago’s western suburbs. It remained his home until he died at the age of 91. It remains Mary’s home today.

What a wonderful story and glad he had a great life afterwards. So many stories of that generation will never be told and that’s sad. I wish my father had given us more of his story.

Thanks for sharing this story. Very interesting to hear all the diary entries and how meticulous Ed was about writing them.