By Nathan N. Prefer

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese caught the United States Army Air Forces units in the Philippines on the ground late on December 8. That airstrike effectively removed General Douglas MacArthur’s air assets from the campaign, although those remaining fought to the end with great courage and skill against an overwhelming force. With air superiority now assured, the Imperial Japanese Army landed troops on Bataan Island on December 8. More troops were landed at Aparri and Vigan on December 10. These landings on northern Luzon were weakly opposed, the untrained and ill-prepared Philippine Army units were simply unable to handle the onrushing Japanese.

From the Palau Islands additional landings were made on December 12 at Legaspi. The island of Mindanao was invaded, also from the Palaus, on December 20. Jolo Island was invaded Christmas Eve. The main Japanese landings in the Philippines also came Christmas Eve at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon between San Fernando and San Fabian. These new troops—43,110 men of the 14th Army—quickly made contact with those coming from north of Luzon and pushed away the Filipino troops protecting the gulf beaches. The American and Philippine forces on Luzon were now faced with enemy troops advancing from the north and south. General MacArthur’s earlier plan to defend Luzon at the beaches was no longer viable.

This was quickly realized, and as early as December 12 MacArthur had advised Philippine President Manuel Quezon to be prepared to move the seat of government to Bataan and evacuate the capital city of Manila. Unwilling to concede his home to the enemy, MacArthur delayed issuing the order, but the continued advance of the Japanese from both directions and the lack of effective air or naval support forced his hand. By December 23, the decision was made and the necessary orders issued. General MacArthur’s headquarters issued the order, “WPO-3 in in effect.”

War Plan Orange 3 was one of several prewar plans dealing with potential enemies of the United States in the event war broke out. Each potential enemy was given a different color, and the plans were numbered accordingly. The Orange War Plans were directed at Japan, and WPO-3 covered the defense of the Philippines. It assumed that Japan would attack without a declaration of war and with less than 48 hours warning. Such conditions would make it impossible for the United States to send reinforcements to the Philippines before the Japanese struck. The defense, therefore, would have to be conducted by the American and Filipino forces already in the islands until the United States could force a path to send reinforcements. The Philippine island of Luzon was expected to be the main Japanese objective. Its wide plains already supported many military airfields, and Manila harbor was ideal for both naval and merchant shipping.

Under WPO-3, the mission of the Filipino garrison was to hold the entrance to Manila Bay and deny its use to the Japanese until relieved by forces from the United States. They were to immediately establish themselves on the Bataan Peninsula after moving all their supplies, equipment, and ammunition to the peninsula. General MacArthur had initially ignored this plan and tried to hold as much of Luzon as he could, only to find that he could hold none of it outside Bataan and the several fortified islands in Manila Bay, including Corregidor. But his delay had disrupted his own schedule. The last minute rush to move troops, supplies, and equipment into Bataan left far too much behind.

The defense of Bataan began on January 7, 1942, when Maj. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright assumed command of the West Sector of the Bataan Defense Force. Later renamed the I Philippine Corps, General Wainwright’s corps shared the responsibility for Bataan with Maj. Gen. George M. Parker, Jr., whose II Philippine Corps held the eastern sector of the defenses. Once all the units were in position, General MacArthur reported to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshal in Washington, “I am on my main battle line awaiting general attack.” The Japanese soon obliged General MacArthur and for the next four months pounded his troops with air, artillery, tank, and infantry attacks. Because of the lack of sufficient supplies, particularly food, the troops became steadily weaker, sicker, and less able to hold their defenses. By April there were 12,000 patients in the understaffed and underequipped hospitals, many lying out in the open, there being insufficient facilities to house them.

General Wainwright had assumed command when General MacArthur was ordered to Australia to command the growing American buildup there. He now commanded all forces in the Philippines from the fortified island of Corregidor in Manila Bay. Things on Bataan were deteriorating rapidly. The Japanese had broken through the last defensive line. There were no combat-viable units left to Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., who now commanded on Bataan. Despite orders to counterattack, General King decided to surrender to prevent any more deaths among his troops. General Wainwright, under specific orders from MacArthur not to surrender, objected. Having no other reasonable choice, King surrendered the 78,000 men of the Bataan Defense Force on April 9, 1942. The first Battle of Bataan had ended.

The horrific details of the events following the surrender are well known. The Bataan Death March and the brutal conditions of the prisoner of war camps and “hell-ships” to Japan are well documented. Bataan itself remained largely ignored by the Japanese once the American and Filipino forces surrendered throughout the islands. Having opened Manila Bay and Manila itself, both of which became major supply points for their advances farther south and east, Bataan had no importance to them.

Not so General MacArthur. Upon arrival in Australia, he had made his famous declaration concerning the Philippines: “I shall return.” No sooner had he settled in Australia than he began to plan and organize that return. It would be a long and bloody road. The years 1942, 1943, and early 1944 were spent struggling up the New Guinea coast, seizing the Solomon Islands, the Admiralty Islands, Hollandia, Biak, Sansapor, and many other heavily contested battlefields from the now retreating Japanese. It was not until October 20, 1944, that MacArthur was able to make good his promise, when under his command Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth U.S. Army landed on Leyte in the central Philippines. That bloody and difficult struggle lasted for three months, but MacArthur was already planning his return to Luzon and, of course, to Bataan.

General MacArthur’s plans for recovering Luzon changed many times because of the evolving military situation in the Pacific. However, he had always planned for the main invasion force to land at Lingayen Gulf, over the same beaches the Japanese had invaded the island in 1941. General Krueger’s Sixth U.S. Army would land its X and XXIV Corps there once they had been relieved by Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger’s Eighth U.S. Army on Leyte. Lingayen Gulf provided direct access to General MacArthur’s main objectives on Luzon, the Central Plains, and the Manila Bay region. Subsidiary landings were to be made at several other sites on the island, many of them identical to those used by the Japanese. Not all of these would actually be executed due to changing military circumstances.

One of those changing circumstances was the unexpectedly fierce Japanese defense of Manila. MacArthur expected that the Japanese would, as he himself had done, declare Manila an “open city” and abandon it. Although the senior Japanese commander in the Philippines, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, planned to do exactly that, his subordinate senior naval commander decided otherwise and conducted a brutal, bloody, and tragic battle for the city. This delay placed a great strain logistically on the Sixth U.S. Army, since until Manila Bay was available its supplies, equipment, and reinforcements had to come across the invasion beaches and through a smaller base at Nasugbu Bay, which had just been seized by the 11th Airborne Division.

By the conclusion of the battle for Manila, the XIV Corps had cleared the eastern shore of Manila Bay. But to ensure the security of Manila harbor it would be necessary to occupy the Bataan Peninsula, which formed the bay’s western shore. Although Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall’s XI Corps had landed recently northwest of Bataan, it had not yet advanced into the peninsula. General Krueger asked MacArthur what his plans were for Bataan.

MacArthur had originally thought that General Yamashita would withdraw his forces into Bataan and make his stand there. However, Yamashita did not follow MacArthur’s plans. His orders were to hold as long as possible to occupy American forces that might otherwise be used to invade the home islands of Japan. Yamashita saw Bataan as a trap in which his troops could be penned, releasing most of the American forces for other objectives. Instead, he left behind delaying forces and withdrew slowly into the deep recesses of the mountainous interior of Luzon, where he would hold out with significant forces until the end of the war.

Unaware of General Yamashita’s views on Bataan, General MacArthur instructed his staff to capture Bataan as soon as possible. With his XIV Corps still heavily involved in clearing Manila and that shore, Krueger gave the Bataan assignment to the XI Corps. Its commander, Maj. Gen. Charles Philip Hall, was born in Sardis, Mississippi, and attended the University of Mississippi before graduating from West Point in 1911. Commissioned in the infantry, he served with the 2nd Division in France during World War I, where he earned a Distinguished Service Cross and several Silver Stars. Wounded in action, Hall returned and between the wars graduated from the Command and General Staff School and the Army War College. At the outbreak of World War II, Brig. Gen. Hall was with the 3rd Infantry Division. After briefly commanding the 93rd Infantry Division, he was promoted to command of the XI Corps in 1942.

General Hall’s XI Corps consisted of the 38th Infantry Division reinforced with the 34th Infantry Regimental Combat Team from the veteran 24th Infantry Division. Originally prepared to land at Vigan, 100 miles north of Lingayen Gulf, the operation had been cancelled in fear of a strong Japanese air reaction from Formosa. Intelligence that Filipino guerrillas had already taken control of much of that area reduced the threat of a flank attack against the Lingayen beachhead. Instead, XI Corps was ordered to land on the Zambales coast of Luzon northwest of Bataan. The plan was for XI Corps to cut off any Japanese attempt to withdraw significant forces into Bataan. A secondary mission was to secure airfields in the San Antonio-San Marcelino area for Allied use. Third, XI Corps was to strike the right rear of a large Japanese force, known as the Kembu Group, which was still delaying the XIV Corps clearance of Manila Bay.

Intelligence reports placed some 13,000 Japanese troops in and around Bataan. About 8,000 of these were within the peninsula itself, the remainder protecting the northern approaches. In fact, there were only about 4,000 troops in Bataan. These were the understrength 39th Infantry Regiment, 10th Division. This unit had been ordered to Leyte, but before it could leave Luzon, Leyte had fallen to the Americans. General Yamashita had then diverted the regiment to Bataan. Commanded by Colonel Sanenobu Nagayoshi, the two infantry battalions were reinforced by two provisional infantry companies, a platoon of light tanks, a reinforced artillery battery, and smaller Army and Navy base defense detachments. Known to the Japanese as the Nagayoshi Detachment, it was nominally under the command of the Kembu Group, which had ordered it to withdraw from Bataan. Unfortunately, XI Corps cut its withdrawal route before Colonel Nagayoshi could exit the Bataan peninsula.

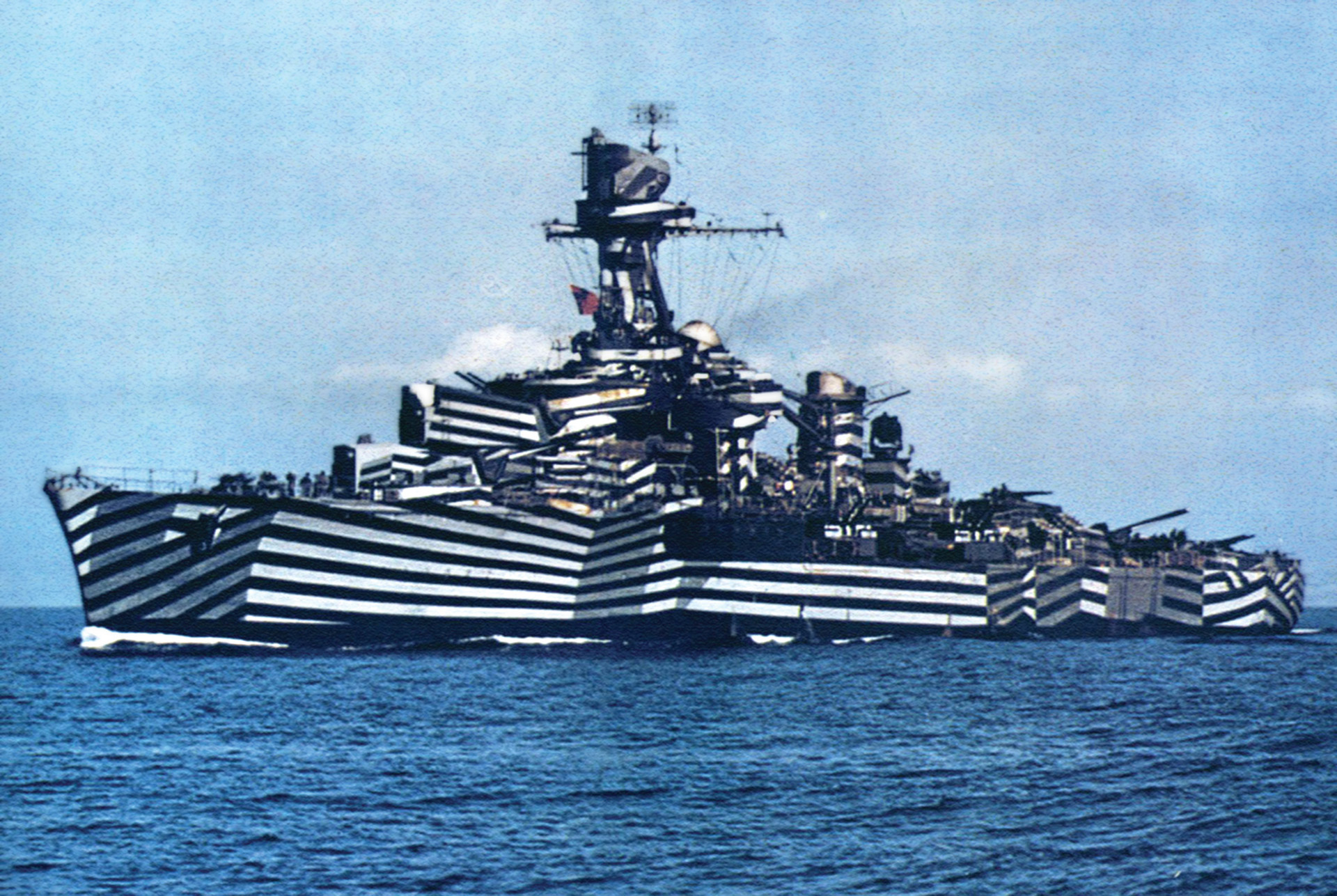

Nagayoshi had no choice but to prepare to defend himself. He assigned his 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry with the tanks and most of the artillery, to block Route 7, which ran along the base of the Bataan Peninsula. One provisional company garrisoned Olongapo, a former American base. A company of the 2nd Battalion, 39th Infantry, defended San Marcelino Airfield, while the rest of the detachment held scattered outposts along the eastern, western, and southern shores of Bataan. Coming at the Japanese were some 40,000 American troops of the XI Corps, including 5,500 Army Air Forces engineers preparing to restore San Marcelino airstrip. Covered by elements of the Seventh U.S. Fleet and Fifth Army Air Force planes, the XI Corps landed on January 29 with no bombardment, having learned from Filipino guerillas that there were no Japanese defenders in the area. Indeed, the first waves of assault troops were greeted by cheering and waving Filipinos who quickly lent a hand unloading supplies.

Major General Henry Lawrence Cullem Jones had commanded the 38th Infantry Division since April 1942. A native of Brokenbow, Nebraska, he had been commissioned into the cavalry after graduating from the University of Nebraska. He had attended the Command and General Staff College, the Army War College, and the Field Artillery School before assuming command of the division, which was formed from the National Guards of Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Although the 149th Infantry Regiment of the division had participated in repelling a Japanese airborne counterattack on Leyte, this was the first combat action for the full division.

Even as the Filipinos helped unload the transport ships, General Jones ordered Colonel Winfred G. Skelton’s 149th Regiment to rush inland and seize San Marcelino Airfield. This they did, only to find Filipino guerrillas under Captain Ramon Magsaysay already in possession of the field. Nearby, the 34th Regimental Combat Team, under Colonel William W. Jenna, reinforced by the 24th Infantry Division’s Reconnaissance Troop, also rushed forward along Route 7 to the north shore of Subic Bay, reaching it before nightfall. No serious Japanese opposition was encountered. Indeed, the only casualty during the day was one enlisted man of Company F, 151st Infantry Regiment, who was gored by one of the ill-tempered Filipino carabaos.

But the Japanese knew the Americans were there. Second Lieutenant Hiroshi Abe, commanding a platoon of 37mm antitank guns posted at Kalaklan Point, reported to Major Horonori Ogawa, commanding the 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry, that he could see about 40 ships following two American destroyers that appeared to be scouting Subic Bay.

The next day a reinforced 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry Regiment landed on Grande Island at the entrance to Subic Bay. Lt. Col. L. Robert Mottern’s men were pleased to find no Japanese in occupation, and they quickly secured Fort Wint, a prewar American coast defense position. Subic Bay was now secured for American base development. So far XI Corps had had an easy time, the worst difficulty being poor beach conditions that delayed some unloading.

The objective now became cutting off and clearing Bataan, then making physical contact with XIV Corps. General Hall ordered the 38th Infantry Division, less Colonel Ralf C. Paddock’s 151st Infantry Regimental Combat Team kept in corps reserve, to pass through the 34th Infantry Regimental Combat Team at Olongapo and drive east along Route 7 using two regiments in mutually supporting advance routes. General Jones selected Colonel Robert L. Stilwell’s 152nd Infantry to move east along Route 7, while two battalions of Colonel Skelton’s 149th Infantry were to support the main effort along a rough trail that was believed to parallel Route 7 on higher ground. Jones expected that any opposition found along Route 7 would be bypassed by Colonel Skelton’s men, forcing the Japanese to withdraw rather than be outflanked. Although Jones set no timetable for the operation, Hall expected that Route 7 would be cleared around February 5.

Despite warnings from Filipino guerrillas under Lt. Col. Gyles Merrill that there were up to 5,000 Japanese armed with machine guns, artillery, tanks, antitank guns, and mortars well dug in along Route 7, the XI Corps staff seems to have largely discounted that intelligence. The 152nd Infantry’s own estimate of the opposition indicated only 900 Japanese in front of it as it began its drive along Route 7. In fact, Colonel Nagayoshi had three times that many men dug in and ready for the approaching Americans.

Lieutenant Colonel Edward M. Postlethwait, from Kansas City, Missouri, and the West Point Class of 1937, led the advance with his 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment. The advance seized Subic Town without opposition. Then the attached 24th Division Reconnaissance Troop took the lead, followed by the 3rd Battalion in trucks, in turn followed by Lt. Col. Charles E. Oglesby’s 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry. The terrain was difficult, with many twists and turns along the road that offered a defender many options for an ambush. This was not ignored by Major Ogawa, and he placed Lieutenant Abe’s 2nd Platoon, 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry in position for just such an ambush near Kalaklan Point.

Armed with two antitank guns and 600 rounds of ammunition, Abe set up near a lighthouse on a projecting spit of rocks. Reinforced with a light machine gun squad under Sergeant Tadashi Ogaki and a second machine gun from the regiment’s 10th Company, Abe also had a few engineers under Sergeant Isoo Miyake, who prepared the road for demolition. Extensive trenches and other field fortifications protected the Japanese from the expected American attack. To the Japanese, the ambush site was known as the ‘Waters Edge Position.” Unfortunately, the guns were sited against an expected landing at Olongapo and, being well dug in, could not fire on Route 7.

Supported by Lt. Col. Thomas Long’s 63rd Field Artillery Battalion with 105mm howitzers, the 24th Division Reconnaissance Troop moved forward, followed by Company I, 34th Infantry under 1st Lt. Paul J. Cain. As the Americans advanced, friendly artillery fire fell in front of them. No artillery observer had been assigned to the advance, and so calls quickly went back to Colonel Long’s battalion to cease fire. But in the early moments Lieutenant Cain did not know whose artillery was firing, so he dismounted his men and sent 2nd Lt. John W. McFayden’s 3rd Platoon forward to investigate. Seeing the Americans preparing to attack, the Japanese opened fire.

First Lieutenant Richard V. Collopy’s 24th Division Reconnaissance Troop immediately returned fire with machine guns and antitank guns mounted on jeeps. Meanwhile, Cain deployed his platoons to clear a cemetery and knock out the enemy machine guns. Unsure of what they had walked into, Cain also called for support. Colonel Postlethwait sent up the 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company and the regimental cannon company, the latter with self-propelled 75mm guns. Second Lieutenant Kenneth E. Yeoman’s 2nd Platoon, supported by the cannon company guns, cleared the machine guns and advanced toward a bridge. To prevent this, the Japanese engineers blew a hole in the road leading to the bridge, but their effort failed to halt the Americans. Engineers of Company C, 3rd Engineer Combat Battalion, a part of the combat team, rushed forward and placed steel matting over the hole, much to the amazement of the Japanese, who reported the incident as the engineers building a bridge over the hole so easily that even “tanks started forward on the steel plates as if nothing had happened.” The battle cost the Americans three men killed and three wounded. Japanese losses were 14 killed.

At this point the 38th Infantry Division was to pass through the 34th Regimental Combat Team and assume the advance. Accordingly, on January 31, the 152nd Infantry assumed the lead along Route 7 while the 149th Infantry turned left and began to follow the trail that paralleled the road. General Hall expected the job to be done by February 5, despite repeated warnings from Colonel Merrill that the Japanese had dug in deep at a place along Route 7 known as Zig Zag Pass.

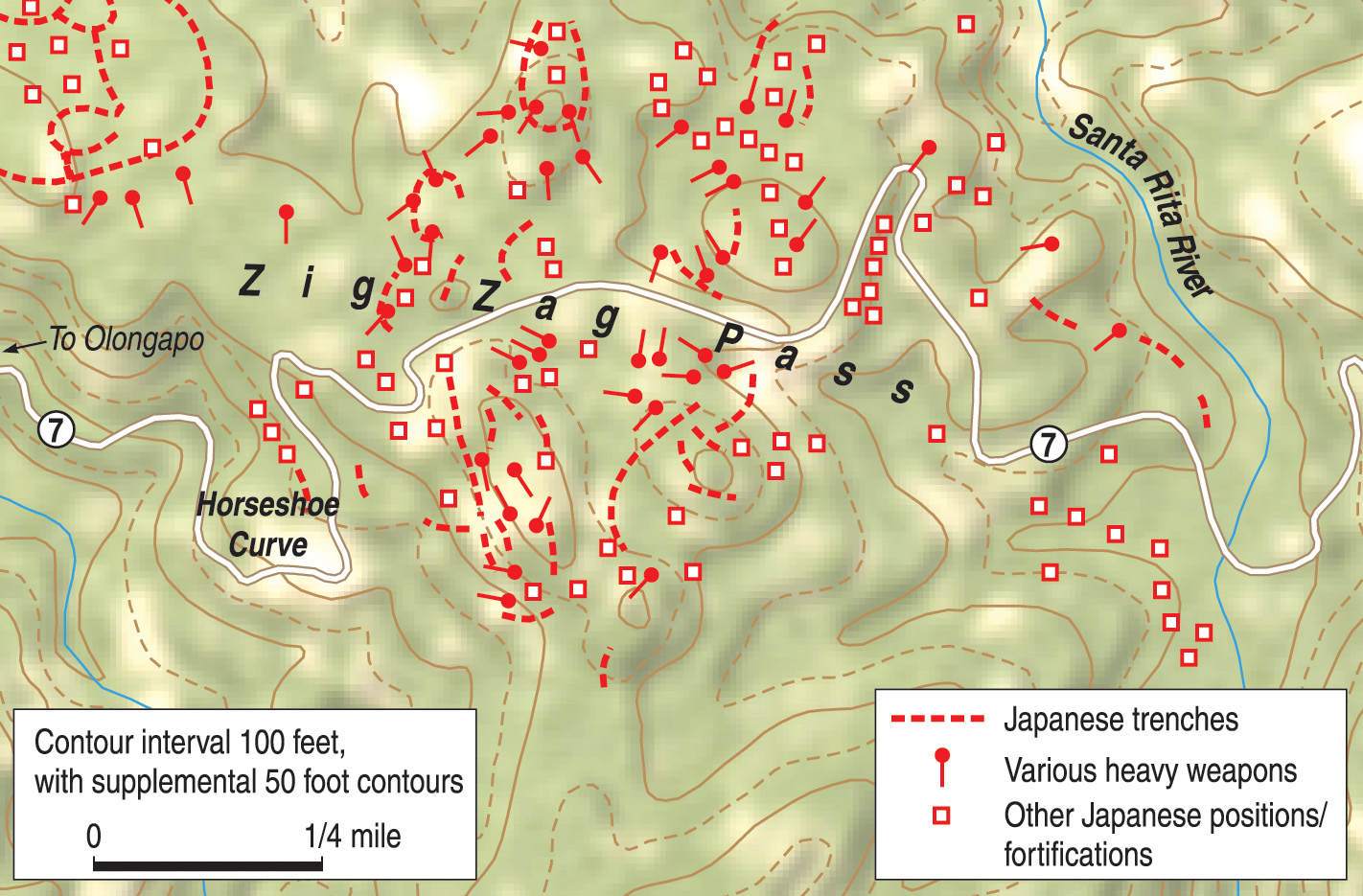

Zig Zag Pass lay along Route 7 in rough terrain. Colonel Nagayoshi had deployed his men in strong mutually supporting positions for three miles along the road. Here the route twists violently through the pass, following a line of least terrain resistance that animals might have originated. The jungle is particularly thick in the area, so thick that five steps off the highway an individual vanishes from sight. Foxholes linked by tunnels and trenches covered the Japanese positions. Log and dirt pillboxes housed the heavy weapons. All defenses were well camouflaged. Mortars and machine guns were generously supplied with ammunition. Artillery was scattered to avoid American counterbattery fire, but this prevented Nagayoshi from concentrating his own artillery fire.

Early on January 31, the 152nd Infantry moved past Olongapo to a point where Route 7 began its climb into the mountains. Opposed only by scattered rifle fire and long-range machine-gun fire, the advance approached Zig Zag Pass. The following day the attack continued against increasing enemy opposition. Another problem surfaced. So difficult was the terrain and so twisted the road that Colonel Stilwell and his staff had difficulty locating where they were on the already inaccurate maps used by corps and division. Again due to the terrain, the Americans’ radios often failed to function or could not reach far. To further hinder communications, the radio code used by the 38th Infantry Division was susceptible to garbling, making successful communications even more difficult. It happened that division and corps believed that the 152nd Infantry had reached and passed a position known as Horseshoe Curve on February 1, when in fact the 152nd Infantry had yet to reach that position. General Hall was less than pleased with their progress.

Lieutenant Colonel Delbert D. Cornwell’s 1st Battalion, 152nd Infantry hit the Japanese defenses early. Enemy fire from well-concealed positions on heights overlooking the road halted the advance and forced individual platoons and companies to search out the enemy in almost impossible terrain. As the 1st Battalion moved into the pass, the 3rd Battalion, under Major Harold B. Mangold, came under fire from the rear. Again, the Americans had to disperse and search out cleverly hidden enemy positions. Little progress was made during the day.

After dark a group of soldiers personally chosen by Major Oawa and led by 2nd Lt. Shozo Nakano of the 9th Company launched a series of squad-sized night attacks. Each squad was reinforced with a light machine gun, a heavy machine gun, and a mortar. Their mission was simply to create havoc in the American rear, shooting up tents, vehicles, supply depots, and artillery positions. Armed additionally with Molotov cocktails, bottles filled with gasoline and given a makeshift fuse, they spread confusion and terror among the novice Americans. “That night being our first in the pass, we dug in about six inches. When the first rounds started falling, you could hear mess kits, shovels—everybody using anything to dig in deeper,” remembered Pfc. Halbert Smith of C Company. Lieutenant Nakano’s attacks caused several casualties in the 2nd Battalion, including the death of the executive officer, Major Shirley N. Duer. Three men were killed, five wounded, and one was missing.

From postwar studies it appears that one company of the 152nd Infantry did manage to reach the Horseshoe Curve on Route 7 during February 1-2, 1945. But they were forced to withdraw when support could not reach them. The Japanese position was already being officially described as a “hornet’s nest.” The 1st Battalion spent the day trying to identify the Japanese positions and find an approach to them. All three battalions suffered casualties from the repeated Japanese night attacks. By dawn of February 2, the regiment had suffered 12 men killed and 48 wounded, while two were missing. And this was only the first day.

The regiment planned to sweep both sides of Route 7 on February 2, which it believed would smash the way past the enemy defenses and clear Zig Zag Pass. But before this could be put into motion the 3rd Battalion, 152nd Infantry came under fire from a previously undisclosed enemy position to the north. They soon found these defenses strong and were unable to make any progress against them. As it happened, the battalion had attacked the center of Colonel Nagoyoshi’s defenses. Because the Japanese had dug in along a line parallel to the road, the 3rd Battalion was forced to the southeast, while the 2nd Battalion, alongside, encountered almost no opposition.

The 1st Battalion remained stymied against the Horseshoe defenses. Again, at dark the positions of the leading battalions of the 38th Infantry Division were reported differently than the positions recorded at headquarters. General Jones believed that all three of his battalions were at or within the Horseshoe position, while in fact only the 1st Battalion, 152nd Infantry was at that point. February 2 had cost the regiment five killed, 26 wounded, and one man missing. The regiment reported that it was only sure of killing 12 enemy soldiers so far in the battle. They had, however, captured a Japanese map giving the entire layout of Colonel Nagoyoshi’s defenses.

General Hall had come up front and visited the regiment about noon on February 2. He found the battalions only beginning their attack and was dissatisfied with the manner in which the attack was being conducted. One battalion commander, when asked by General Hall, admitted he had no idea where the enemy was and had only one patrol looking for them. Another had no answer when asked why he had started his attack so late. General Hall advised General Jones that the 38th Infantry Division’s progress was the worst he had ever seen. Despite the fact that he viewed only one regiment of the division and that the regiment he observed was in only its second day of combat, Hall made his displeasure known to Jones.

General Jones, who had himself been up front with the leading patrols, was equally unhappy, particularly with the performance of the 3rd Battalion. He relieved Colonel Stillwell and replaced him with the regiment’s executive officer, Lt. Col. Jesse E. McIntosh. The situation of the 149th Infantry Regiment was little better. Although not strongly opposed deep in the jungles, the regiment reported itself at a location that aerial observers said was at least three miles in advance of where it actually was. Further, artillery fired in support of the regiment landed so far away, based on Colonel Skelton’s reports, that he could hear it but not see it. Radio communications soon failed. In effect, Jones had lost contact with the regiment.

Unsure if the relief would have the desired effect on the 152nd Infantry, General Hall also ordered up the 34th Infantry Regimental Combat Team. The combat team would operate under the direct control of the XI Corps, not the 38th Infantry Division, an unusual command structure. Colonel McIntosh’s 152nd Infantry was now to follow behind the 34th Infantry Regiment and mop up bypassed pockets of resistance. When Jones requested the use of the division reserve, Colonel Mottern’s 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry, Hall grew angry and told him he had more than enough troops to clear Zig Zag Pass. Hall, still believing that only a handful of Japanese manned an outpost line of resistance, left Jones, in effect, a regimental commander.

Colonel Jenna’s 34th Infantry Regiment came up on February 3 and passed through the 152nd Infantry under mortar and artillery fire. The attack made some progress, but the Horseshoe still defied the Americans. Behind the 34th Infantry, the battalions of the 152nd Infantry sent out patrols, which knocked out several enemy strongpoints.

The attack of February 4 did better, but at dark the Americans had to surrender much of the ground gained to settle into defensible positions. As a result, the actual ground gained was not great. General Jones complained that the demand by General Hall for speed did not allow him sufficient time to make artillery adjustments to clear the way for his troops. That would have been news to the Japanese. Communications Sergeant Tamotsu Nagai of the Heavy Machine Gun Company returned to a forward position after visiting another. He was shocked by the devastation that had hit the area since he had departed. He asked Private Nagaharu Kobayashi, a machine gunner, what had happened. It was explained that when the guns had opened fire American artillery had replied with such force that it had cleared the hill of all trees and most of the vegetation.

Although the 34th Infantry was a veteran regiment that had made an outstanding name for itself, including a Presidential Unit Citation for the 1st Battalion during the Leyte campaign, most of the men who had been with the regiment were no longer present. Including the former regimental commander, some 78 percent of the men who had landed with the regiment on Leyte were now gone, dead, wounded, missing, or ill. It had made more progress than the 152nd Infantry, but it had not, as General Hall expected, broken through. Realizing that divided command was dangerous in such a situation, Hall reattached the 34th Infantry to the 38th Division. But the attack of February 3 did finally convince Hall that his XI Corps was facing a strong Japanese defense at Zig Zag Pass.

General Jones wanted to reduce the Japanese defenses with a methodical and simultaneous attack by battalions of his 152nd Infantry Regiment. The 34th Infantry Regiment would concentrate on the Horseshoe area and reduce it. Because it was so difficult to direct artillery support in the terrain and jungle, Jones limited artillery support to east of the Santa Rita River (also called Jadjad River). This slowed the response time to requests for artillery support.

Colonel Jenna objected to the placement of his regiment between the battalions of the 152nd Infantry Regiment. Instead, he recommended that his regiment take the south side of Route 7 and Colonel McIntosh’s regiment take the north side. General Jones denied his request, fully realizing that his methods were much slower than the quick results General Hall was continuing to demand. Jones actually wanted to pull the two regiments back, pound the Japanese positions for two days with artillery, mortar, and air support, and then launch a full two-regiment attack, but the delay would not be agreeable to General Hall, so Jones went ahead with the deliberate attack.

February 5 began promisingly with advances by both regiments. But then the Japanese mortars and artillery opened fire, causing several casualties, and a withdrawal was made again. Colonel Jenna requested that the artillery pound the enemy for a day or two before another attack, buying into Jones’s ideal plan, but under pressure from XI Corps Jones ignored the suggestion. In two days of battle, Colonel Jenna had lost more than 325 battle casualties and another 25 as nonbattle losses, more than it had lost in 78 days of combat on Leyte. The regiment was no longer combat effective, and Hall ordered Jones to replace it with his own 151st Infantry Regiment.

The 1st Battalion, 152nd Infantry made good progress on February 5, clearing a ridge held by the Japanese. Enemy opposition stiffened in the afternoon, but progress continued until nightfall, when the battalion occupied abandoned Japanese defenses. But just as the Americans were settling in for the night, Japanese troops armed with rifles and machine guns began to spring up out of some of the concealed holes and open fire. Confusion reigned as the Americans and Japanese were closely intermingled. Supporting fire could not be used, and the men of the 152nd Infantry could not even fire in their own defense since that risked hitting friendly forces all around them. The only way to escape was to withdraw, which the battalion did until they reached the lines of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry. Nine men had been killed and 33 wounded. Company C had lost all its officers, and Company B had but one officer left. By the morning of February 6, no progress had been made in Zig Zag Pass for four days.

There was some good news on February 6. Colonel Skelton reported that his 149th Infantry had reached Dinalupihan and made contact with XIV Corps. The earlier loss of communications had in fact resulted in progress being made. Although recalled three times by General Jones, Skelton had never received those orders. Conversely, Skelton had twice asked Jones for new orders, received no response, and continued his originally assigned mission. As a result, one of the main objectives of XI Corps had been accomplished. The Japanese had been sealed off within the Bataan Peninsula.

Meanwhile, General Hall’s dissatisfaction with the 38th Infantry Division had reached the breaking point. The fault lay, he believed, with General Jones’ leadership. On February 6, Hall again went up front to observe operations. He found no attack, but the infantry waiting for an air strike, then a scheduled artillery bombardment, before moving forward. When Jones replied to Hall’s inquiry that he expected the artillery fire to last most of the day, Hall ordered him to cease the artillery and get the 152nd Infantry moving forward. It was apparently on his way back that General Hall decided a new commander was necessary. He ordered General Jones relieved and replaced him temporarily with the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Roy W. Easley. The next day Brig. Gen. William C. Chase was brought over from the 1st Cavalry Division to assume permanent command.

The command change did little to improve ,the battle for Zig Zag Pass. February 7 and 8 were marked by the same halting advances due to Japanese mortar and artillery fire. But unlike General Jones, who had only one regiment under his command, General Chase was soon able to employ all three regiments of the 38th Infantry Division. The 149th Infantry attacked from the east, behind the Japanese. The 151st and 152nd Infantry Regiments attacked together into the pass. Aircraft now flying from San Marcelino Airfield dropped napalm and bombs on reported Japanese positions. Corps and division artillery battalions were moved up and used extensively. Still, the Japanese resisted with their usual ferocity and determination, holding on for another week under an increasing weight of American firepower.

It was not until February 15 that the 149th Infantry and the 152nd Infantry joined hands from their respective sides of Zig Zag Pass. By that time the Japanese had lost almost 2,400 officers and men killed. The 300 survivors retreated deeper into Bataan with Colonel Nagayoshi and held out there, starving and being hunted by Filipino guerrillas. The 38th Infantry Division and the attached 34th Regimental Combat Team had lost 1,400 casualties, including 250 killed, during the battle for Zig Zag Pass.

General Hall still had to clear the Bataan Peninsula. He sent the 1st Infantry Regimental Combat Team, 6th Infantry Division, under the command of Brig. Gen. William Spence, artillery commander of the 38th Infantry Division, down the east side of the peninsula, while the 151st Regimental Combat Team cleared the west side. Opposition consisted of isolated groups of Japanese that were quickly overcome. Colonel Nagayoshi had fewer than 1,200 troops dispersed throughout the peninsula, most at Bagac on the west coast road.

Opposed by guns from Corregidor in the bay, the Americans were able to advance steadily. Small groups of Japanese soldiers were eliminated. During a visit to General Spence’s headquarters on February 15, General MacArthur’s party advanced past the leading patrols and was nearly wiped out when Fifth Air Force planes requested permission to bomb and strafe his column, believing they had spotted a retreating Japanese force.

Joined by the 149th Infantry and other elements of the 38th Infantry Division, the American forces cleared Bataan during the rest of February. Only stragglers and abandoned positions were found. For a cost of 50 killed and 100 wounded, XI Corps killed an additional 200 Japanese and secured Manila Bay. Colonel Nagayoshi and his remaining 1,000 men holed up in the thickly jungled slopes of Mount Natib, ironically the site of an early Japanese breakthrough during the first Battle for Bataan in 1942. Most of them would die of starvation. In September 1945, Colonel Nagayoshi and the remaining 250 men of his original force of 4,000, surrendered to American military police in a local village.

The 38th Infantry Division continued its war, participating in the seizure of the fortified islands in Manila Bay, then relieving the 6th Infantry Division in the Montalban sector during which they seized Mount Pinatubo, Woodpecker Ridge, the Shimbu Line, Wawa Dam, and Sugar Loaf Hill. By June the division was ordered to clear southern Luzon, mopping up when the war ended.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.